Historic Cherokee settlements

The historic Cherokee settlements were Cherokee settlements established in Southeastern North America up to the removals of the early 19th century. Several settlements existed prior to—and were initially contacted by—explorers and colonists of the colonial powers as they made inroads into frontier areas. Others were established later.

In the beginning of the 18th century, an estimated 2100 Cherokee people inhabited more than sixteen towns east of the Blue Ridge Mountains and across the Piedmont plains in what was then considered Indian country.[1][2][3][notes 1] Generally European visitors noted only those towns with townhouses. Some of their maps included lesser settlements, but "the centers of towns were clearly marked by townhouses and plazas."[4]

These early Cherokee towns east of the Blue Ridge Mountains were geographically divided into two regions: the Lower Towns (of the Piedmont coastal plains in what are now northeastern Georgia and western South Carolina), and the Middle/Valley/Out Towns (east of the Appalachian Mountains). A third group, the Overhill Towns, located on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains, made up the remainder of the Cherokee settlements of the time.[3] Within each regional group, towns exhibited close economic, linguistic, and religious ties, and often were developed for miles along rivers and creeks.[1] Satellite villages were positioned in close proximity to the regional towns and often bore the same or similar names to the regional centers. These minor settlements shared architecture and a common culture, but maintained political autonomy.[1]

Town locations

No list could ever be complete of all Cherokee settlements; however, in 1755 the government of South Carolina noted several known towns and settlements. Those identified were grouped into six "hunting districts:" 1) Overhill, 2) Middle, 3) Valley, 4) Out Towns, 5) Lower Towns, and 6) the Piedmont settlements, also called Keowee towns, as they were along the Keowee River.[5] In 1775 – May 1776, explorer and naturalist William Bartram described a total of 43 Cherokee towns in his Travels in North America, after living for a time in the area. Cherokee were living in each of them.[5][6]

The Cherokee also established new settlements—or moved existing settlements—using the same or very similar names from one location to another, as the names were associated with a community of people.[4] This practice complicated the historical recording and tracking by Europeans of many early settlement locations.[7] Examples of this practice of repeated names include "Sugar Town," "Chota/Echota," and "Etowa/h," to name just a few.[7]

Lower / Keowee settlements

The Lower Towns in that period were considered to be those in the northern part of the Colony of Georgia and northwestern area of the Colony of South Carolina; many were based along the Keowee River,[5] including: the major towns of Seneca and Keowee New Towne; as well as, Cheowie, Cowee, Coweeshee, Echoee, Elejoy, Estatoie, Old Keowee, Oustanalla, Oustestee, Tomassee, Torsalla, Tosawa (also later spelled Toxaway), Torsee, and Tricentee.[5][8] In addition, since the late 20th century, archeologists have identified historic Cherokee townhouses dating from the sixteenth through the early eighteenth century[1] at the towns known as Chauga (where the Cherokee were identified as occupying it in the last of four phases) and Chattooga site, both in present-day western South Carolina; and Tugalo, in present-day northeastern Georgia. The latter site is now inundated by Lake Hartwell.[4]

Middle, Valley, and Out Towns

The Middle Towns of western North Carolina Colony were primarily along the upper Little Tennessee River and its tributaries.[9] The Cherokee towns and related settlements in this area included Comastee, Cotocanahuy, Euforsee, Little Telliquo, Nayowee, Nuckasee, Steecoy, and Watoge.[1]

Since the late 20th century, the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and partners have reacquired some of these former town sites in their homeland for preservation. These include the sites of Nuckasee, Steecoy, and Watoge along the Little Tennessee River. These will be featured as part of the planned "Nikwasi-Cowee Corridor".[10][11][12]

The Valley Towns consisted of those along the upper Hiwassee River and its tributary the Valley River, and the Nantahala River, which flowed into the Little Tennessee River from the south. These rivers were all south of the Little Tennessee.[9][13] Valley Towns included Chewohe, Tomately, and Quanassee.[5]

The Out Towns were located slightly north of the Little Tennessee, mainly along its tributary the Tuckaseegee River and its tributary, the Oconaluftee River.[9] Towns and settlements included Conontoroy, Joree, Kittowa (the 'mother town' of the Cherokee, which was reacquired by the EBCI in 1996), Nununyi, Oustanale, Tucharechee, and Tuckaseegee.[5][8]

Overhill settlements

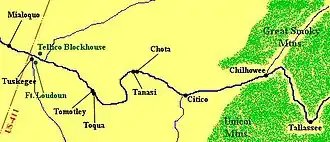

Both the Little Tennessee River and the Hiwassee River flowed through the mountains into what is present-day Tennessee, where they ultimately each flowed into the Tennessee River at different points. Early Cherokee Overhill settlements included those on the lower Little Tennessee River: Chilhowee, Chota, Citico, Mialoquo, Tallassee, Tanasi, Tomotley, Toqua, and Tuskegee (Island Town); those on the Tellico River: Chatuga and Great Tellico; and those on the lower Hiwassee River: Chestowee and Hiwassee Old Town.[1][13][5][8]

1776 town losses

Following the failed two-prong attack against the frontier settlements of the Washington District in the summer of 1776, the colonies of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia mounted a retaliatory attack against all the Cherokee towns. It was known as the Rutherford Light Horse expedition, and militias attacked the Cherokee on both sides of the mountains, destroying many towns. The Cherokee had allied with the British in the hopes of expelling European Americans from their territory. After these attacks, the Cherokee sued for peace with the Americans. By January 1777 the Upper Town Cherokee had made a peace.[14]

New towns period

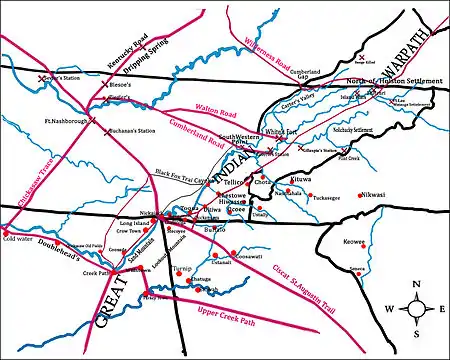

A large following of Cherokee, however, refused to settle with the encroaching Americans and moved further south. Under the war chiefs Dragging Canoe, Black Fox, and Little Turkey, they settled many additional locations throughout the southeastern United States, mostly driven by events of the ongoing Cherokee–American wars they were engaged in.[1] This Chickamauga faction moved further downstream on the Tennessee River system, establishing 11 new towns well away from the American frontier.[14]

Following further conflicts with the military of the fledgling Unites States, in 1782 Dragging Canoe established five new "Lower Towns" even further downstream along the Tennessee River. The original five towns included: Running Water town (Amogayunyi) (Dragging Canoe's new headquarters); Long Island on the Holston (Amoyeligunahita); Crow Town (Kagunyi); Lookout Mountain town (Utsutigwayi, or Stecoyee); and Nickajack (Ani-Kusati-yi, meaning Koasati Old-place). The Chickamauga also re-established a small military presence in Tuskegee Island Town at this time.

Additional settlements in the area were quickly developed, following the arrival of more members to join Dragging Canoe's force. These people were now known more properly as the Lower Cherokee, as opposed to Chickamauga. Their settlements included the major, regional town of Creek Path town (Kusanunnahiyi); Turkeytown; Turnip town (Ulunyi); Willstown (Titsohiliyi); and Chatuga (Tsatugi).[15]

Leadership

The Cherokee were highly decentralized and their towns were the most important units of government.[16][13] The Cherokee Nation did not yet exist. Before 1788, the only leadership role that existed with the Cherokee people was a town's or region's "First Beloved Man" (or Uku).[17] The First Beloved Man would be the usual contact person and negotiator for the people under his leadership, especially when dealing with European or frontier government representatives.[16][17]

Starting in 1788, a supreme First Beloved Man was elected to run a national Cherokee council. This group alternated between meeting at Willstown and Turkeytown, but it convened irregularly and had little authority with the people. The First Beloved Man of each town still maintained a substantial amount of authority.[18] The murders of the Overhill pacifist chiefs—including Old Tassel, the regional headman—who that same year were lured to parley with the State of Franklin and ambushed instead, resulted in an increasingly violent period between the Cherokee and American settlers. A definitive peace was finally achieved in 1794. The ambush had resulted in driving many of the Upper Cherokee, who at the time were more supportive of some adaptation to European-American ways, into union with the Lower Cherokee leadership.

By the time of Dragging Canoe's death (January 29, 1792), the Cherokee settlements of the Lower Towns had increased from five to seven. The re-populated New Keowee was still the principal town of the region.[18] Up until 1794, when the fighting stopped and the national council ground moved to Ustanali,[14] the Cherokee remained a fragmented people. At the founding of the first Cherokee Nation in 1794, the now united people still controlled a large area encompassing lands now located in several states, including: Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama.

The Cherokee Nation's five regional councils of 1794 comprised 1) the Overhill Towns; 2) the Hill Towns; 3) the traditional Valley Towns; 4) the new Upper Towns (these were the former Lower Towns of southern North Carolina, western South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia); and 5) the new Lower Towns (newly occupied settlements located in north and central Alabama, southeastern Tennessee, and far northwestern Georgia).

Peacetime

The constant warfare took its toll on the traditional Cherokee settlements. Several had become permanently de-populated by the turn of the 19th century. The settled areas stabilized for a time following the 1794 establishment of the Cherokee Nation and partial acculturation[14] of the people in the east. Following The Removal era (1815–1839), however, many of these settlements were all but abandoned forever.

.jpg.webp) Cherokee Nation c.1760[19]

Cherokee Nation c.1760[19].jpg.webp) A Draught of the Cherokee Country, Henry Timberlake (1762) Overhill Towns

A Draught of the Cherokee Country, Henry Timberlake (1762) Overhill Towns Post-Revolution Cherokee towns

Post-Revolution Cherokee towns Native American settlements of the Southeastern United States (1806)

Native American settlements of the Southeastern United States (1806)

Cherokee settlements

| Town or settlement | Native & alternate names |

Syllabary | Location today |

State | Group* | Site status |

Notable resident(s) | Importance notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Fox | Inaliyi | ᎡᎾᎵᏱ | On the Clinch River near Black Fox, Bradley County, Tennessee | TN | LT-11 |

|

(before 1788) | Established by Dragging Canoe's Chickamauga Cherokee faction, c.1777; flooded by Norris Lake |

| Cayuga town | Cayoka | ᎦᏳᎦ | On Hiwassee Island in Hamilton County | TN | LT-11 |

|

established by Dragging Canoe | |

| Chatanugi | Tsatanugi | ᏣᏔᏄᎩ | Along Chattanooga Creek in St. Elmo neighborhood, Chattanooga, Hamilton County | TN | LT-11 |

|

Choctaw-nooga was established by Dragging Canoe[notes 2] | |

| Chatuga[5][1] | Tsaduga Chatugee |

ᏣᏚᎦ | Polk County | TN | OH |

|

Sister-town of Great Tellico.[1] | |

| Chestowee[1] | Chestue | ᏤᏍᏚᎢ | on the Hiwassee River in Bradley County | TN | MVO |

|

Originally a Yuchi settlement whose fall to the Cherokee marked their rise as a regional power. | |

| Chickamagua town | Tsikamagi | ᏥᎦᎹᎩ | On the Tennessee–Georgia line; along Chickamauga Creek | TN | LT-11 |

|

A Creek town occupied by those following Dragging Canoe in 1776–1777; became common frontier name for his faction of Cherokee. | |

| Chilhowee[1] | Tsulunwe Chilhowey |

ᏧᎷᎾᎢ | Along the Little Tennessee in Monroe County | TN | OH |

|

|

Originally the Muscogee town of Chalahume; on the Little Tennessee River;[notes 3] burned in late 1776 prior to William Christian's combined ranger and militia attack during the Cherokee War of 1776;[20] flooded by the Chilhowee Lake. |

| Chota[1][5] | Echota Chote Itsati Itsasa[1] |

ᎢᏣᏘ or ᎢᏣᏌ | On the Little Tennessee River in Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

[1] | Principal city of the Overhill Cherokee, c.1748–1788;[1] flooded by Tellico Lake. |

| Citico Old Towne[1][5] Satapo |

Settacoo Sittiquo |

ᏎᏖᎫ | In Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

Probable location of "Satapo Village" visited by Juan Pardo; near the confluence of the Little Tennessee River and the lower Tellico River, The Cherokee abandoned and burned the town —along with several other Overhill settlements—prior to, or immediately following, the attacks on the Wautaga settlements in mid-1776, and what was left of the town and fields were razed in late 1776 by the William Christian's Virginian combined ranger and militia element during the Cherokee War of 1776;[20] flooded by Tellico Lake. | |

| Citico[1][5] | Sitiku | ᏎᏔᎫ | In Chattanooga, Hamilton County | TN | LT-11[5] |

|

|

Moved to Chickamauga Creek area from the Old Towne before 1777, as its entire population followed Dragging Canoe south; archeological site demolished for a private college student-housing development in 2017. |

| Coyotee town | Coyote | ᎪᏲᏘ | TN | OH | ||||

| Ducktown[21] | Gawonvyi Kawana[22] |

ᎦᏬᏅᏱ | Ducktown, Polk County | TN | OH |

|

|

In the 1840s and 1850s, Ducktown was called "Hiwassee" or "Hiawassee."[21] |

| Great Hiwassee[1] | Ayuhwasi Egwaha Euphase |

ᎠᏴᏩᏏ ᎢᏆᎭ | Polk County | TN | OH |

|

Important Overhill Cherokee town located along the Hiwassee River.[1][notes 4] | |

| Great Island[1][5] | Mialoquo Amayelegwa Big Island |

ᎠᎹᏰᎴᏆ | Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

|

Under the leadership of Attakullakulla, father of Dragging Canoe; burned in late 1776 by William Christian's combined ranger and militia element during the Cherokee War of 1776;[20] an island now submerged in the Little Tennessee River. |

| Great Tellico[1] | Telliquo Talikwa |

ᏔᎵᏆ or ᏖᎵᏉ | near Tellico Plains in Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

|

Principal city of the Cherokee 1730 – c.1748; burned in late 1776 prior to William Christian's combined ranger and militia attack during the Cherokee War of 1776;[20] |

| Little Tellico[1] | Little Telliquo | TN | OH | Sister village of Great Tellico. | ||||

| Long Island on the Holston | Amoyeli-gunahita | ᎠᎼᏰᎵ ᎫᎾᎯᏔ | Site is now Kingsport, Tennessee on border of Sullivan – Hawkins counties | TN | LT-5 |

|

||

| Nickajack | Koasati place Ani-Kusati-yi (Niquatse’gi) |

ᎠᏂ ᎫᏌᏘ Ᏹ (ᏂᏆᏤᎩ) | Marion County | TN | LT-5 |

|

(after 1782) | Nickajack Cave and surrounding areas were settled and inhabited by Chickamauga starting c.1777; site partially flooded by the Nickajack Lake in 1967.[notes 5] |

| Ocoee | Ocoee | ᎣᎪᎢ | Ocoee, Polk County | TN | OH |

|

||

| Ultiwa | Ooltewah | ᎤᎳᏘᏩ | Near Ooltewah, Hamilton County | TN | LT-11 |

|

Founded by the skiagusta, Ostenaco. | |

| Opelika | Opelika | ᎤᏇᎵᎦ | Near East Ridge, Hamilton County | TN | LTK |

|

||

| Running Water town | Amogayunyi | ᎠᎼᎦᏳᎾᏱ | now Whiteside, Marion County | TN | LT-5 |

|

Later Chickamauga head-town | |

| Sawtee | Itsati | ᎢᏣᏘ | Between South Sauta Creek and North Chickamauga Creek in Hamilton County | TN | LT-11 |

|

|

|

| Tallassee[1][5] | Talassee Talisi Tellassee |

ᏔᎵᏏ | near the Calderwood, a ghost town in Blount County | TN | OH[5] |

|

Southernmost of the Overhill Cherokee towns; population left after signing of the Treaty of Calhoun (1819); site submerged by Chilhowee Lake.[notes 6] | |

| Tanasi[1][5] | Tenessee | ᏔᎾᏏ | On Little Tennessee River, Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

|

Principal city of the Cherokee until 1730;[1] site submerged by Tellico Lake. |

| Tomotley[1][5] | Tamahli | ᏔᎹᏟ | Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

|

Site is adjacent to Toqua, one of its satellite villages;[1] flooded by Tellico Lake. |

| Toqua[1][5] | Dakwayi | ᏓᏆᏱ or ᏙᏆ | Monroe County | TN | OH[5] |

|

|

Adjacent to Tomotley; burned in late 1776 prior to William Christian's combined ranger and militia attack during the Cherokee War of 1776;[20] re-occupied by Dragging Canoe c.1777; flooded by Tellico Reservoir. |

| Tuckasegee | Tuckasegee Dvkasigi |

ᏛᎧᏏᎩ | Far East Tennessee Unicoi Mountains | TN | MVO |

|

|

Site very near the North Carolina–Tennessee state line and the town of Tuckasegee. |

| Tuskegee Island Town[1][5] | Taskigi Toskegee |

ᏔᏥᎩ | Near Williams Island in Chattanooga, Monroe County | TN | OH / (LT-5)[5] |

|

[1] | Burned in late 1776 prior to William Christian's combined ranger and militia attack during the Cherokee War of 1776;[20] but re-occupied by the Chickamauga at the time of the move to the five Lower Towns; site submerged by Tellico Reservoir. |

| Wautaga[23] | Watagi[24] | ᏩᏔᎩ | On the Wautaga River next to Elizabethton, Carter County[23] | TN | OH |

|

Burned 1776. | |

| Cane Creek[25][8] | Coweeshee Coweshe |

ᎪᏫᏍᎯ | On Cane Creek[25] in Oconee County. | SC | LTK |

|

A satellite village of Keowee; burned along with its corn fields by Neel (1776). | |

| Canuga town[25] | Canugi | ᎧᏅᎦ | On the Keowee in Pickens County[25] | SC | MVO |

|

||

| Chatuga Old Town[25] | Tsatugi Chatogy |

ᏣᏚᎩ | On the Chattooga River, Oconee County[25] | SC | MVO |

|

Burned in 1776 by Col. Neel in the Williamson Campaign.[25] | |

| Chauga[25] | Chawgee[25] Takwashwaw |

ᏣᎤᎩ or ᏔᏆᏍᏆ | Between the Tugaloo and Seneca Rivers in Oconee County[25] | SC | MVO |

|

Flooded by Lake Hartwell on the Tugaloo. | |

| Cheowee[25] | Chiowee Chehowee; |

ᏤᎣᏫ or ᏥᎣᏫ | Oconee County[25] | SC | MVO |

|

Cherokee fled from Creek incursions in 1752; town burned in 1776 by Col. Neel in the Williamson Campaign.[25] | |

| Cowee[5][8] | SC | LTK |

|

|||||

| Ustanately[5][8] | Ustana'li' Eustanali |

ᎤᏍᏔᎾᏟ | On the Keowee River in Oconee County | SC | LTK |

|

Abandoned in late 1751 when Creek Indians attacked. | |

| Ecochee[25] | Echy Echay Echia |

ᎡᎪᏥ or ᎡᏤ | On the Savannah River and the Toxaway Creek. | SC | LTK |

|

"...Forsaken and destroyed..."[25] by 1770. | |

| Ellijay[25][5] | Elijoy Elatse'yi' |

ᎡᎳᏤᏱ | Oconee County[25] | SC | LTK |

|

Was near the headwaters of Keowee on the site of old Camp Jocasse (early 1900s);[25] one of three settlements with this name; | |

| Estanari | Oustlnare lstanory |

ᎡᏍᏔᎾᎵ | Oconee County[25] | SC | LTK |

|

||

| Eustaste[25][8] | Ousteste Ustustee Oustana[25] |

ᎤᏍᏖᏍᏖ | SC | LTK |

|

Destroyed in 1776 by Williamson.[25] | ||

| Estatoie[25][5] | Eastato Eslootow Oustato Easttohoe[25] |

ᎡᏍᏔᏙᏪ | On the Tugalo River[25][8] | SC | LTK |

|

Estatoe was moved just downstream from the Old Estatoe site; Estatoe Old Towne was a regional political center from 1730 to at least 1753; occupied by the Creeks (late 1750s); re-populated by Cherokee afterward; Montgomerie burned the town in 1760[25] and Williamson in 1776. | |

| Seneca Old Towne[24] | Isunigu Esseneca Senekaw |

ᎢᏑᏂᎬ | On the Keowee River, near present-day Clemson and Seneca in Oconee County. | SC | LTK |

|

Attacked prior to the Battle of Twelve Mile Creek involving Williamson's force; flooded by Lake Hartwell reservoir;[notes 7] the modern day town of Seneca, South Carolina is its namesake, although the meaning of the transliterated "Isunigu" is lost.[25] | |

| Old Keowee[7][5] | Keyhowe | ᎨᎣᏫ | On the Keowee River in Oconee County.[25] | SC | LTK | Located along the Lower Cherokee Traders Path; it was the largest of the "Lower Towns" and part of the Upper Road through the Piedmont; across the river from Fort Prince George; destroyed by the British, Creeks, and Chickasaws in 1760;[25] flooded by Lake Keowee.[26] | ||

| Keowee New Towne[25] | Kuwoki Little Keowee[25] |

ᎫᏬᎩ | West of Keowee, on Mile Creek in Pickens County.[25] | SC | LTK |

|

Established 1752 following the break-up of the Lower Towns in anticipation of Creek raids;[25] Expedition under James Grant killed all male inhabitants in 1760 (woman and children spared); this is the "Keowee" destroyed by Pickens and Williamson in 1776; de-populated c.1816 when residents moved to Qualla Boundary.[25] | |

| Noyowee | Nayowee No-a-wee |

ᏃᏲᏫ | On the Chauga River in Oconee County | SC | LTK |

|

Attacked by the Creek in 1724; destroyed during the Williamson Campaign ot 1776;[25] there were several Lower Towns named Nayowee.[25] | |

| Oconee Town[25] | Ae-quo-nee Uquunu |

ᎤᏊᏄ | Near Oconee Station,[28] in the Pickens District now Oconee County. | SC | LTK |

|

The British razed the town in 1760; the Americans burned it in 1776;[25] was at the intersection of the Indian trading path and the Cherokee treaty boundary of 1777; Oconee County is its namesake.[25] | |

| Qualhatchie[25] | Qualahatchie Quaratchee Qualucha[25] |

ᏆᎳᎭᏥ | Straddled Crow Creek | SC | LTK |

|

British Colonel Montgomerie burned the town in 1760; in 1776, it was again burned to the ground—without a battle—by the Americans.[25] | |

| Saluda Old Town | Tsaludiyi | ᏣᎷᏗᏱ | Below Ninety-Six, Greenwood County | SC | LTK |

|

One of the seven original Cherokee mother towns.[notes 8] | |

| Socony | Soquani Socauny[25] |

ᏐᏆᏂ | Site is at the junction of Twelve Mile River and Town Creek, near Pickens, Pickens County | SC | LTK |

|

The easternmost of the Cherokee settlements in 1775; burned in 1776 by Col. Neel in the Williamson Campaign.[25] | |

| Sugar Town of Toxso[24][25] | Conasatchee Kulsetsiyi[25] |

ᎫᎳᏎᏥᏱ | Above Fort Prince George (on the Keowee River near Salem in Oconee County)[25] | SC | LTK |

|

|

Sacked and burned in 1760 by the British; destroyed by Williamson raid August 4, 1776; flooded by Lake Jocassee reservoir; there were several historic towns named "Sugartown" in the Cherokee lands of the southeastern United States; this is the most documented location.[7][24][25] |

| Tamassee Town[29][25] | Tomassee Tomatly[25][8] |

ᏔᎹᏏ | On the Little River system of Oconee County.[25] | SC | LTK |

|

Was abandoned during the Creek wars of the 1740s & 1750s; re-populated by 1775; burned in 1776 during the Williamson Campaign; was the site of Andrew Pickens' tactical "Ring fight" against the towns' Cherokee defenders in 1776.[25] | |

| Torsalla[5][8] | SC | LTK |

|

|||||

| Torsee[5][8] | SC | LTK |

|

|||||

| Toxaway[5][8] | Toicksaw Tusoweh Toxsaah[25] |

ᏚᏆᏌᎢ | On Toxaway River in Oconee County.[25] | SC | LTK |

|

|

Burned by Montgomery in 1760; rebuilt by 1762; burned during American Revolutionary War expedition and finally abandoned on August 6, 1776.[25] |

| Tricentee[5][8] | ᏟᏎᎾᏘ | Oconee County.[25] | SC | LTK |

|

A satellite of Cane Creek.[25] | ||

| Tucharechee | Takwashuaw | ᏚᏣᎴᏥ | Oconee County | SC | LTK |

|

||

| Brasstown[30] | Brass Ûňtsaiyĭ Itse'yĭ' |

ᎡᏦᏪ | Site is now Brasstown Clay and Cherokee counties[30] | NC | MVO |

|

One of several locations with the "Brasstown" name.[25][notes 9] population removed to Indian Territory in 1838. | |

| Chewohe[5] | Chewohee | ᏤᏬᎯ | NC | MVO |

|

|||

| Conoske[1] | Comastee | NC | MVO |

|

||||

| Cotocanahuy[1] | NC | MVO |

|

|||||

| Etowah mountain town | italwa | ᎡᏙᏩ | Near Etowah, Henderson County | NC | LTK |

|

Burned in the Rutherford Light Horse expedition;[31][notes 10] | |

| Euforsee[1] | NC | MVO |

|

|||||

| Joree[5][8] | Jore | ᏲᎵ | NC | MVO |

|

|

||

| Kituwa[5][8] | Keetoowah Giduwa[25] |

ᎩᏚᏩ | Just outside Bryson City, Swain County | NC | MVO[25] |

|

Principal town of the original seven Cherokee settlements, or "mother towns;"[25] Abandoned in 1761 when inhabitants fled west and founded Great Island Town.[32] | |

| Nanthahala | Aquone | ᎠᏉᏁ | Site near Aquone Macon County, North Carolina community | NC | MVO |

|

Submerged by Nantahala Lake. | |

| Nikwasi [5][8] | Noquisi Nequassee |

ᏃᏈᏍᎢ or ᏁᏆᏍᎢ | Site is along Little Tennessee River in Franklin, Macon County | NC | MVO |

|

No-kwee-shee was destroyed by Rutherford; residents forced into the Qualla Boundary in 1819; a platform mound is the only extant feature left of the town. | |

| Nayuhi[1] | Nayowee | ᎾᏳᎯ | On the Valley River in Cherokee County, North Carolina | NC | MVO |

|

There were several Lower Towns named 'Nayowee.'[25] | |

| Nununyi[1] | Nuanha | ᏄᏄᎾᏱ | On the Oconaluftee River, near present-day Cherokee | NC | MVO |

|

One of the seven mother towns of the Cherokee; destroyed by Rutherford; the main platform mound is still largely intact (2020); listed on the NRHP in 1980. | |

| Spike Buck Town[33] | Quanassee Quanasi |

ᏆᎾᏏ | Town developed around a mound along the Hiwassee River; today it is in downtown Hayesville[33] | NC |

|

Listed on the NRHP and designated a memorial site in Veterans Recreational Park.[34] | ||

| Sugar Town on the Cullasaja[24] | Kulsetsi[24] | ᎫᎳᏎᏥᏱ | Site on the Cullasaja River and very near Nikwasi town) on the Little Tennessee River in Macon County[24] | NC | MVO |

|

One of several "Sugartowns;"[24] satellite town of Nikwasi.[25] | |

| Tomotla[35][30] | Tomahli Tamali Tomotli |

ᏔᎹᎵ or ᏙᎼᏟ | Near Tomotla, Cherokee County[30] | NC | MVO |

|

The name "Tomotla" is from the historic Yamasee inhabitants before they were expelled by the Cherokee in 1715. The Cherokee periodically inhabited the town.[30] | |

| Too-Cowee[5][8] | Cowee Stecoah Steecoy |

ᏤᎪᎠ | Located on the Little Tennessee River, north of present-day Franklin, North Carolina, Macon County | NC | MVO |

|

Badly damaged in late 1776 by the Rutherford Light Horse expedition; re-populated following the raid, but eventually abandoned | |

| Ustalli[5][8] | Ustaly; Oustanale |

ᎤᏍᏔᎵ | On the upper Hiwassee River in Clay County | NC | MVO |

|

Burned in a John Sevier raid in 1788. | |

| Watauga village[23] | Wattoogi Watoge[23] |

ᏩᏚᎩ | Mound and village on the Little Tennessee near Franklin, Macon County[23] | NC | MVO |

|

||

| Brasstown[25][5] | Echoee Etchowee |

ᎡᏦᏪ | Site is on Upper Brasstown Creek (tributary to the upper Hiwassee), somewhere near Brasstown, Oconee County | GA | MVO |

|

One of several locations with the "Brasstown" name; this one is near Brasstown Bald.[25] | |

| Buffalo | Yunsayi | ᏴᎾᏌᏱ | Near Ringgold, Catoosa County | GA | LT-11 |

|

Founded by Dragging Canoe as part of the relocation of Cherokee away from white settlements. | |

| Conasauga[36][37] | Cunasagee | ᎫᎾᏌᎩ | Site is in Gilmer County | GA | LT |

|

Now a ghost town.[36][notes 11] | |

| Coosawattee town[25] | Kuswatiyi | ᎫᏌᏩᏘᏱ | GA | LTK |

|

"Old Coosa Place"[7] | ||

| Chatuga[38] | Head-of-Coosa[38][7] | ᏣᏚᎦ or ᎢᏙᏩ | Rome, Floyd County[39] | GA | LLT |

|

(See Etowah New Towne) | Was a satellite village of, and built close to, Etowah New Towne; site holdings auctioned off to citizens of Georgia, in 1839, along with Etowah New Towne.[38] De-populated by forced removal of Cherokee in 1838. |

| Etowah New Towne | Hightower[40] | ᎡᏙᏩ | Now Rome, Floyd County[39] | GA | LLT |

|

[39] | Town site near the confluence of the Oostanaula and Etowah rivers, which forms the Coosa River (the "Head of the Coosa", Chatuga);[38] site holdings auctioned to citizens of Georgia, 1839;[38] de-populated by forced removal in 1838; the Battle of Hightower, the Last Battle of the Cherokee occurred here on October 17, 1793.[41] |

| Etowah Old Towne | Old Hightower[40] | ᎡᏙᏩ | On the north shore of the Etowah River near Cartersville, Bartow County | GA | LTK |

|

Site is across the Etowah (Hightower) River from the Etowah Indian Mounds. | |

| Lookout Mountain town | Utsutigwayi Stecoyee |

ᎤᏧᏘᏆᏱ or ᏤᎪᏱ | Is now the site of Trenton, Dade County | GA | LT-5 |

|

|

Established by Dragging Canoe; he died here in 1792. |

| Nacoochee | Nagutsi Nagoochee |

ᎾᎫᏥ | On the coastal plane; on the Chattahoochee River in White County | GA | LT |

|

Sometimes called "Chota."[notes 12] | |

| New Town / New Echota | Ganasagi Kanasaki |

ᎦᎾᏌᎩ | Calhoun, Gordon County | GA | LLT |

|

Capital of the Cherokee Nation in the Southeastern United States from founding as New Town (1819) until their forced removal in the 1830s; renamed 'New Echota' in 1825; site abuts historic site of former capital, Ustinali; de-populated by the Trail of Tears 1830s; vacant for over 100 years; now a state park. | |

| Red Clay[42] | Elawa'-Diyi | ᎡᎳᏬᏗᏱ | Now Red Clay, Whitfield County | GA | LLT |

|

||

| Sugar town on the Toccoa[25] | Connetoga Kulsetsiyi |

ᎫᎳᏎᏥᏱ | At the confluence of the Toccoa River and Sugar Creek, in Georgia[24] | GA | LLT |

|

One of several Cherokee settlements named "Sugartown".[25][24] | |

| Tugalo[25] | Dugiluyi Toogoloo Toogalooh |

ᏚᎩᎷᏱ | At junction of Tugalo River and Toccoa Creek near present-day Toccoa in Stephens County | GA | LTK |

|

|

An ancient, abandoned Creek Indian town; re-settled by Cheokee, but attacked by the Creeks in 1724; burned by Pickens on August 10, 1776 following the [[Battle of Tugaloo}; excavated 1956 by Dr. Joseph Caldwell before completion of Hartwell Dam; flooded by Lake Hartwell. |

| Turnip town | Ulunyi | ᎤᎷᎾᏱ | Seven miles from Rome, Floyd County | GA | LLT |

|

||

| Ustinali | Oothacaloga Oostanaula |

ᎤᏍᏘᎾᎵ or ᎤᏍᏔᎾᎵ | Near Calhoun, Gordon County | GA | LT-11 |

|

|

National Council meeting place (capital city) from 1809 to 1819; site abuts New Echota Town; The name, Ustinali, was sometimes used interchangeably with New Echota in reference to the home of the Cherokee National Council. |

| Brown's Village[43] | On Brown's Creek, near Red Hill, Marshall County[44][43]}} | AL | LLT |

|

|

|||

| Coldwater | Near Muscle Shoals (Dagunohi), Colbert County; | AL | LLT |

|

Joint occupation by Chickamauga and Chickasaw; Doublehead's base of operations during the Cherokee–American wars; razed by James Robertson's Cumberland militia in 1787; then became site of Colbert's Ferry, the Tennessee River crossing-place of the Natchez Trace trail. | |||

| Coosada | Coosadi | ᎫᏌᏓ | In Coosada, Elmore County | AL | LLT |

|

||

| Cornsilk Village[43] | Unenudo | ᎤᏁᏄᏙ | On Cornsilk Pond, 1.5 miles south of Warrenton Marshall County | AL | LTT |

|

|

|

| Creek Path town | Kusanunahi[43] | ᎫᏌ ᏄᎾᎯ | Site is four miles southeast of Guntersville, Marshall County[43] | AL | LLT |

|

Very Important regional Cherokee town with a population of 400–500; close to Browns Town.[43] | |

| Crow Town | Kagunyi | ᎧᎫᎾᏱ | Near Stevenson, Jackson County | AL | LT-5 |

|

Sister-town of, and located near to, Running Water town | |

| Littafulchee | Litafulche | ᎵᏔᏡᎳᏥ | Along Canoe Creek, Calhoun County | AL | X |

|

Probably originally a Creek Indian town. | |

| Tallaseehatche | ᏔᎳᏏᎭᏥ | In Calhoun County | AL | X |

|

Originally a Creek Indian or Chickasaw town. | ||

| Turkeytown | ᎫᎾᏗᎦᏚᎱᎾᏱ | Near Centre, Cherokee County | AL | LT-11 |

|

"Turkey's Town" (Gun'-di'ga-duhun'yi) was named after the founder of the settlement, Chickamauga, Little Turkey, a war chief of Dragging Canoe's. At one point it stretched for about 25 miles along both banks of the Coosa, being the largest of the contemporary Cherokee towns; seat of the Lower Towns council after 1794, alternating with Willstown until 1809. | ||

| Willstown[45] | Titsohili | ᏘᏦᎯᎵ | Near Fort Payne, DeKalb County[45] | AL | LT-11 |

|

Seat of the Lower Towns council after 1794, alternating with Turkeytown until 1809;[45] large settlement stretching from DeKalb to Etowah counties. | |

See also

Notes

- "Cherokee "towns" were settlements equipped with a great hall or council halls (Cherokee:gatuyi, or town house); villages and satellite settlements usually had no communal great halls."

- "-nooga" means "dwellers" in Cherokee

- "Chilhowee" is a Cherokee corruption of the Muskogean Chalahume, the town's original occupants

- Hiwassee means "savanna" or "plain."

- Nickajack had been known to those that had dealings with the Muscogee as Coushatta town (or Koasati town), meaning Koasati place, or place of the Coushatta people (those of the Coosa chiefdom). The Chickamauga called it Niquatse’gi (pronounced Nee-kwa-j[ch]ay-k[g]ee).

- This Tallassee should not be confused with modern Tallassee, Tennessee.

- Seneca Town was on the west side of the Keowee River, near the mouth of Coneross Creek, in today's Oconee County.

- Tsaludiyi translates as "green corn place."

- Ûňtsaiyĭ translates to "brass; Itse'yĭ' translates to "new green place."

- The word Etowah comes from the Muskogee/Creek word italwa meaning "town."

- "Conasauga" is a name derived from the Cherokee language, meaning "grass".

- The ancient indian settlement site, Nacoochee, was also called "Chota" for a time.

References

- Schroedl, Gerald F.. "Overhill Cherokees". Tennessee Encyclopedia on-line. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- Edgar, Walter (1998). South Carolina: A History. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press.

- McFall, Pearl (1966). The Keowee River and Cherokee Background. Pickens, S.C.

- Rodning, Christopher B. (Summer 2002). "The Townhouse at Coweeta Creek" (PDF). Southeastern Archeology. 21 (1). Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- Royce, Charles C. (1887). Old Cherokee Towns from The Cherokee Nation of Indians by C.C. Royce. 5th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1883–’84; Powell, J. W., Director. via Tennessee GenWeb online; Tennessee: Government Printing Office. pp. 142–144.

- Bartram, William. Bartram’s Travels in North America – From 1773 to 1778. p. 371.

- "The Names Stayed". Calhoun Times and Gordon County News. August 29, 1990. p. 64. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- "Carolina – The Native Americans (list article) – from Hodge, et al". Carolina Heritage online. November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- Chavez, Will (March 25, 2016). "EBCI ancestors remained east for various reasons". Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- "Cowee Mound preserved for future generations, historic interpretation". Smoky Mountain News. November 1, 2006. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- Ellison, Quintin (July 29, 2019). "Cherokee invest in Nikwasi Mound's future, as preservation efforts pick up steam". The Sylva Herald. Retrieved August 8, 2019 – via Asheville Citizen-Times.

- "Mainspring conserves Historic Cherokee Town". Cherokee One Feather. July 14, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- Cherokee; WebPage; Oklahoma Historical Society online, retrieved January 21, 2021

- Black, Dr. Daryl (February 2, 2014). "Century of Change for the Cherokee". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- Brown, John P. (1938). Old Frontiers: The Story of the Cherokee Indians from Earliest Times to the Date of Their Removal to the West, 1838. Southern Publishers. pp. 175–176.

- Traditional Cherokee Government; edit board; January 24, 2011; WebPage; Native American Roots online; accessed January 21, 2021

- The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire; Hoig, Stanley W.; University of Arkansas Press; (first ed. February 1999/) July 1, 1999); Fayetteville, Arkansas; ISBN 9781557285287; retrieved January 21, 2021

- Malone, Henry Thompson (1956). Cherokee of the Old South. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- Kitchin, Thomas (1760). "A New Map of the Cherokee Nation". London: Carli Digital Collections/Everett D. Graff Collection of Western Americana (Newberry Library). Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- Kurt, Russ; Jefferson Chapman (November 27, 1983). Archaeological Investigations at the Eighteenth Century Overhill Cherokee Town of Mialoquo (40MR3) (Report). 37, Pp. 18–19.

- Barclay, R.E. (1946). Ducktown Back in Raht's Time. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 4–10.

- Outdoors, Cascade. "History of Ocoee River & the Area". cascadeoutdoors.com. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "Mainspring Conserves Historic Cherokee Town". One Feather. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Mooney, James (1900). Myths of the Cherokee. New York: Dover (published 1995).

- Sheriff, ed., G. Anne. "Sketches of Cherokee Villages in South Carolina" (PDF). (physical book is sourced via Roots Web online). scanned copies/images from copyright free book; Oconee Museum copyright holder of Sketches of Cherokee Villages in South Carolina; date August 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Anderson-Oconee-Pickens County SC Historical Roadside Markers". Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "Historical Marker Road Map" (jpg). Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- Edgar, Walter, ed. (2006). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina Press. p. 680. ISBN 1-57003-598-9.

- "Oconee Stories". Oconee Country website. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- "Community Backstory". Cherokee County Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- "About Etowah". Etowah Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008.

- Klink, Karl; Tallman, James (1970). The Journal of Major John Norton, 1816. Toronto: Norton, John, via The Champlain Society (published 2013). ISBN 9780981050638.

- "Spikebuck Mound". Clay County Communities Revitalization Association. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Post Offices". Jim Forte Postal History. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 210–214. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4.

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- Levy, Benjamin (March 5, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: "Chieftains;" Major Ridge House" (pdf). National Park Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) and Accompanying three photos, exterior and interior, from 1972 (32 KB) - "Rome City Commission Archives" (PDF). March 3, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- Cherokee Phoenix. "INDIANS". www.wcu.edu. Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Wilkins, Thurman (1970). Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People. New York: Macmillan Company.

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- "History of Marshall Co., Alabama". Marshall County Government. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- Wright, Jr., Amos J. (2003). Historic Indian Towns in Alabama, 1540–1838. University of Alabama Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8173-1251-X.

- "History of DeKalb County". DeKalb County Tourist Association. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

Further reading

- "An Indian Land Grant in 1734" by Mabel L. Webber; "The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine Vol.19, No.4, pp.157–161"

External links

- Cherokee town map – Compiled from Maps by Stuart, Hunter and Royce

- Mooney's Cherokee Country map (1900) – Map of Cherokee Country by James Mooney

- Cherokee Country Sketch – Sketch of Cherokee Country by John Stuart

- Cherokee Nation Map of 1730 – Map of the Cherokee Nation by George Hunter

- Goodspeed Map – The East Tennessee and Chickamauga towns