History of Christianity in Romania

The history of Christianity in Romania began within the Roman province of Lower Moesia, where many Christians were martyred at the end of the 3rd century. Evidence of Christian communities has been found in the territory of modern Romania at over a hundred archaeological sites from the 3rd and 4th centuries. However, sources from the 7th and 10th centuries are so scarce that Christianity seems to have diminished during this period.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Romania |

|

|

|

The vast majority of Romanians are adherent to the Orthodox Church, while most other populations that speak Romance languages follow the Catholic Church. The basic Christian terminology in Romanian is of Latin origin, though the Romanians, referred to as Vlachs in medieval sources, borrowed numerous South Slavic terms due to the adoption of the liturgy officiated in Old Church Slavonic. The earliest Romanian translations of religious texts appeared in the 15th century, and the first complete translation of the Bible was published in 1688.

The oldest proof that an Orthodox church hierarchy existed among the Romanians north of the river Danube is a papal bull of 1234. In the territories east and south of the Carpathian Mountains, two metropolitan sees subordinate to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople were set up after the foundation of two principalities, Wallachia and Moldavia in the 14th century. The growth of monasticism in Moldavia provided a historical link between the 14th-century Hesychast revival and the modern development of the monastic tradition in Eastern Europe. Orthodoxy was for centuries only tolerated in the regions west of the Carpathians where Roman Catholic dioceses were established within the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century. In these territories, transformed into the Principality of Transylvania in the 16th century, four "received religions" – Catholicism, Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Unitarianism – were granted a privileged status. After the principality was annexed by the Habsburg Empire, a part of the local Orthodox clergy declared the union with Rome in 1698.

The autocephaly of the Romanian Orthodox Church was canonically recognized in 1885, years after the union of Wallachia and Moldavia into Romania. The Orthodox Church and the Romanian Church United with Rome were declared national churches in 1923. The Communist authorities abolished the latter, and the former was subordinated to the government in 1948. The Uniate Church was reestablished when the Communist regime collapsed in 1989. Now the Constitution of Romania emphasizes churches' autonomy from the state.

Pre-Christian religions

.svg.png.webp)

The religion of the Getae, an Indo-European people inhabiting the Lower Danube region in antiquity, was characterized by a belief in the immortality of the soul.[1][2] Another major feature of this religion was the cult of Zalmoxis; followers of Zalmoxis communicated with him by human sacrifice.[1]

Modern Dobruja – the territory between the river Danube and the Black Sea – was annexed to the Roman province of Moesia in 46 AD.[3][4] Cults of Greek gods remained prevalent in this area, even after the conquest.[5] Modern Banat, Oltenia, and Transylvania were transformed into the Roman province of "Dacia Traiana" in 106.[6] Due to massive colonization, cults originating in the empire's other provinces entered Dacia.[7][8] Around 73% of all epigraphic monuments at this time were dedicated to Graeco-Roman gods.[9]

The province of "Dacia Traiana" was dissolved in the 270s.[7] Modern Dobruja became a separate province under the name of Scythia Minor in 297.[7][10][11]

Origin of the Romanians' Christianity

The oldest proof that an Orthodox church hierarchy existed among the Romanians north of the river Danube is a papal bull of 1234. In the territories east and south of the Carpathian Mountains, two metropolitan sees subordinate to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople were set up after the foundation of two principalities, Wallachia and Moldavia in the 14th century. The growth of monasticism in Moldavia provided a historical link between the 14th-century Hesychast revival and the modern development of the monastic tradition in Eastern Europe. Orthodoxy was for centuries only tolerated in the regions west of the Carpathians where Roman Catholic dioceses were established within the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century. In these territories, transformed into the Principality of Transylvania in the 16th century, four "received religions" – Calvinism, Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Unitarianism – were granted a privileged status. After the principality was annexed by the Habsburg Empire, a part of the local Orthodox clergy declared the union with Rome in 1698.

.png.webp)

The core religious vocabulary of the Romanian language originated from Latin.[13] Christian words that have been preserved from Latin include a boteza ("to baptize"), Paște ("Easter"),[14] preot ("priest"),[15] and cruce ("cross").[16][17] Some words, such as biserică ("church", from basilica) and Dumnezeu ("God", from Domine Deus), are independent of their synonyms in other Romance languages.[10][13][16]

The exclusive presence in Romanian language of Latin vocabulary for concepts of Christian faith proves the antiquity of Daco-Roman Christianity;[18][19] some examples are:

- altar(ium) – altar ("altar"),

- baptisare – a boteza ("to baptize"),

- cantare, canticum – cântare, cântec ("sing", "song"),

- crux, cruce – cruce ("cross"),

- communicare ("communicate") – a cumineca ("to receive or give Communion/Eucharist"),

- commendare ("commend, commit") – a comânda ("to sacrifice; to remember or pray for someone who died"),

- credere – a crede ("to believe"),

- credentia – credință ("faith, belief"),

- christianus – creștin ("Christian"),

- draco – drac ("evil", "devil"),

- Floralia ("ancient festival") – Florii ("Palm Sunday"),

- ieiunare – a ajuna ("to fast"),

- ieiunus - ajun ("fast")

- ligare:

- carnem ligare ("tie/bind meat") – cârnelegi, cârneleagă ("penultimate week of Advent fast when meat can be eaten")

- caseum ligare ("tie/bind cheese")– câșlegi,

- luminaria – lumânare ("candle"),

- lex, lege – lege ("law, faith"),

- martyr – martor ("witness"),

- monumentum – mormânt ("tomb"),

- presbyter – preut (preot) ("priest"),

- paganus – păgân ("pagan"),

- pervigilium, pervigilare – priveghi, priveghea ("wake", "to keep watch/vigil for a wake"),

- rogare, rogatio(ne) – ruga, rugăciune (rugă) ("to pray", "praying"),

- quadragesima – păresimi ("Lent"),

- sanctus – sânt (sfânt) ("saint"),

- scriptura – scriptură ("scripture, writing"),

- *sufflitus – suflet ("soul, spirit")

- thymiama – tămâie ("incense"),

- turma – turmă ("flock"), etc.[18][19]

The same is true for the Christian denominations of the main Christian holidays: Crăciun ("Christmas") (from Latin: calatio(ne) or rather from Latin: lacreatio(ne)) and Paște ("Easter") (from Latin: Paschae); Several archaic or popular saint names, sometimes found as elements in place names, also seem to derive from Latin: Sâmpietru, Sângiordz, Sânicoară, Sânmedru, Sântilie, Sântioan, Sântoader, Sântămărie, and Sânvăsii. Today, sfânt, of Slavic origin, is the usual way to refer to saint.[20]

The Romanian language also adopted many Slavic religious terms.[17] For example, words like duh ("soul, spirit"), iad ("hell"), rai ("paradise"), grijanie ("Holy Communion"), popă ("priest"), slujbă ("church service") and taină ("mystery, sacrament") are of South Slavic origin.[17] Even some terms of Greek and Latin origin, such as călugar ("monk") and Rusalii ("Whitsuntide"), entered Romanian through Slavic. Several terms relating to church hierarchy, such as episcop ("bishop"), arhiepiscop ("archbishop"), ierarh ("hierarch"), mitropolit ("archbishop"), came from Medieval or Byzantine Greek, sometimes partly through a South Slavic intermediate[17][21][22][23][24][25][26] A smaller number of religious terms were borrowed from Hungarian, for instance mântuire (salvation)[27] and pildă (parable).[28]

Several theories exist regarding the origin of Christianity in Romania.[29][30][31] Those who think that the Romanians descended from the inhabitants of "Dacia Traiana" suggest that the spread of Christianity coincided with the formation of the Romanian nation.[13][32] Their ancestors' Romanization and Christianization, a direct result of the contact between the native Dacians and the Roman colonists, lasted for several centuries.[13][33] According to historian Ioan-Aurel Pop, Romanians were the first to adopt Christianity among the peoples who now inhabit the territories bordering Romania.[34] They adopted Slavonic liturgy when it was introduced in the neighboring First Bulgarian Empire and Kievan Rus' in the 9th and 10th centuries.[35] According to a concurring scholarly theory, the Romanians' ancestors turned to Christianity in the provinces to the south of the Danube (in present-day Bulgaria and Serbia) after it was legalized throughout the Roman Empire in 313.[36] They adopted the Slavonic liturgy during the First Bulgarian Empire before their migration to the territory of modern Romania began in the 11th or 12th century.[37]

Roman times

Christian communities in Romania date at least from the 3rd century.[38][39][40] According to an oral history first recorded by Hippolytus of Rome in the early 3rd century, Jesus Christ's teachings were first propagated in "Scythia" by Saint Andrew.[29][41] If "Scythia" refers to Scythia Minor, and not to the Crimea as has been claimed by the Russian Orthodox Church, Christianity in Romania can be considered of apostolic origin.[10][29]

The existence of Christian communities in Dacia Traiana is disputed.[29][42] Some Christian objects found there are dated from the 3rd century, preceding the Roman withdrawal from the region.[39][40][43] Vessels with the sign of the cross, fish, grape stalks, and other Christian symbols were discovered in Ulpia Traiana, Porolissum, Potaissa, Apulum, Romula, and Gherla, among other settlements. A gem representing the Good Shepherd was found at Potaissa.[39][40][43] On a funerary altar in Napoca the sign of the cross was carved inside the letter "O" of the original pagan inscription of the monument, and pagan monuments that were later Christianized were also found at Ampelum and Potaissa.[39][44] A turquoise and gold ring with the inscription "EGO SVM FLAGELLVM IOVIS CONTRA PERVERSOS CHRISTIANOS" ("I am Jupiter's scourge against the dissolute Christians") was also found and may be related to the Christian persecutions during the 3rd century.[45]

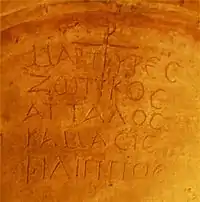

In Scythia Minor, a large number of Christians were martyred during the Diocletianic Persecution at the turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries.[10] Four martyrs' relics were discovered in a crypt at Niculițel, with their names written in Greek on the crypt's inner wall.[46] Thirty-five basilicas built between the 4th and 6th centuries have been discovered in the main towns of the province.[47][48] The earliest basilica, built north of the Lower Danube, was erected at Sucidava (now Celei), in one of the Roman forts rebuilt under Justinian I (527–565).[49][50] Burial chambers were built in Callatis (now Mangalia), Capidava, and other towns of Scythia Minor during the 6th century. The walls were painted with quotes from Psalms.[51]

Clerics from Scythia Minor were involved in the theological controversies debated at the first four Ecumenical Councils.[47] Saint Bretanion defended the Orthodox faith against Arianism in the 360s.[47][52] The metropolitans of the province who supervised fourteen bishops by the end of the 5th century had their See in Tomis (modernly Constanța).[47] The last metropolitan was mentioned in the 6th century, before Scythia Minor fell to the Avars and Sclavenes who destroyed the forts on the Lower Danube.[53][54] John Cassian (360–435), Dionysius Exiguus (470–574) and Joannes Maxentius (leader of the so-called Scythian Monks) lived in Scythia Minor and contributed to its Christianization.[55]

Early Middle Ages

East Roman Empire period

Most Christian objects from the 4th to 6th centuries found in the former province of Dacia Traiana were imported from the Roman Empire.[57] The idea that public edifices were transformed into Christian cult sites at Slăveni and Porolissum has not been unanimously accepted by archaeologists.[10][50] One of the first Christian objects found in Transylvania was a pierced bronze inscription discovered at Biertan.[58] A few 4th century graves in the Sântana de Mureș–Chernyakhov necropolises was arranged in a Christian orientation.[59] Clay lamps bearing depictions of crosses from the 5th and 6th centuries were also found here.[44][57]

Dacia Traiana was dominated by "Taifali, Victuali, and Tervingi" around 350.[60][61] Christian teachings among the Tervingi who formed the Western Goths started in the 3rd century.[62] For instance, the ancestors of Ulfilas, who was consecrated "bishop of the Christians in the Getic land" in 341, had been captured in Capadocia (Turkey) around 250.[63] During the first Gothic persecution of Christians in 348, Ulfilas was expelled to Moesia, where he continued to preach Greek, Latin, and Gothic languages.[64][65][66] During the second persecution between 369 and 372, many believers were martyred, including Sabbas the Goth.[67] The remains of twenty-six Gothic martyrs were transferred to the Roman Empire after the invasion of the Huns in 376.[62][68]

Following the collapse of the Hunnic Empire in 454, the Gepids "ruled as victors over the extent of all Dacia".[69][70] A gold ring from a 5th-century grave at Apahida is ornamented with crosses.[71] Another ring from the grave bears the inscription "OMHARIVS", probably in reference to Omharus, one of the known Gepid kings.[72] The Gepidic kingdom was annihilated in 567–568 by the Avars.[73]

The presence of Christians among the "barbarians" has been well documented.[74] Theophylact Simocatta wrote of a Gepid who "had once long before been of the Christian religion".[74] The author of the Strategikon documented Romans among the Sclavenes, and some of those Romans may have been Christians as well.[74] The presence and proselytism of these Christians does not go so far as to explain how artifacts with Christian symbolism appeared on sites to the south and east of the Carpathians in the 560s.[75] Such artifacts have been found at Botoșana and Dulceanca.[76] Casting molds for pectoral crosses were found in the space around Eastern and Southern Carpathian mountains, starting with the 6th century.[77]

Outer-Carpathian regions and the Balkans

Burial assemblages found in 8th-century cemeteries to the south and east of the Carpathians, for instance at Castelu, prove that local communities practiced cremation[78][79] The idea that local Christians incorporating pre-Christian practices can also be assumed among those who cremated their dead is a matter of debate among historians.[80][81] Cremation was replaced by inhumation by the beginning of the 11th century.[78][82]

For the period from the 9th to 11th centuries, in the regions from the East of Carpathians there are known more than 52 discoveries of Christian origin (moulds, brackets, pendants, groundsels, pottery with Christian signs, rings with Christian signs), many of them locally made; some of these discoveries and the content and the orientation of graves show that local people practised the Christian burial ceremony before the Christianization of Bulgars and Slavs.[83]

The territories between the Lower Danube and the Carpathians were incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire by the first half of the 9th century.[84] Boris I (852–889) was the first Bulgarian ruler to accept Christianity, in 863.[85] By that time differences between the Eastern and the Western branches of Christianity had grown significantly.[86] Boris I allowed the members of the Eastern clergy to enter his country in 864, and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church adopted the Bulgarian alphabet in 893.[87][88] An inscription in Mircea Vodă from 943 is the earliest example of the use of Cyrillic script in Romania.[89]

The First Bulgarian Empire was conquered by the Byzantines under Basil II (976–1025).[90] He soon revived the Metropolitan See of Scythia Minor at Constanța, but this put Christian Bulgarians under the jurisdiction of the archbishop of Ohrid.[91][92] The Metropolitan See of Moesia was reestablished in Dristra (now Silistra, Bulgaria) in the 1040s when a mission of mass evangelization was dispatched among the Pechenegs who had settled in the Byzantine Empire.[93][94] The Metropolitan See of Dristra was taken over by the bishop of Vicina in the 1260s.[95][96]

The Vlachs living in Boeotia, Greece were described as false Christians by Benjamin of Tudela in 1165.[97] However, the Vlach brothers Peter and Asen built a church in order to gather Bulgarian and Vlach prophets to announce that St Demetrius of Thessaloniki had abandoned their enemies, while arranging their rebellion against the Byzantine Empire.[98][99] The Bulgarians and the Vlachs revolted and created the Second Bulgarian Empire.[100] The head of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was elevated to the rank of "Primate of the Bulgarians and the Vlachs" in 1204.[100][101]

Catholic missionaries among the Cumans, who had controlled the territories north of the Lower Danube and east of the Carpathians from the 1070s, were first conducted by the Teutonic Knights, and later by the Dominicans, after 1225.[102][103] A new Catholic diocese was set up in the region in 1228 by Archbishop Robert of Esztergom, the papal legate for "Cumania and the Brodnik lands".[104][105] A letter written by Pope Gregory IX revealed that many of the inhabitants of this diocese were Orthodox Romanians, who also converted Hungarian and Saxon colonists to their faith.[106][107][108]

As I was informed, there are certain people within the Cuman bishopric named Vlachs, who although calling themselves Christians, gather various rites and customs in one religion and do things that are alien to this name. For disregarding the Roman Church, they receive all the sacraments not from our venerable brother, the Cuman bishop, who is the diocesan of that territory, but from some pseudo-bishops of the Greek rite.

Intra-Carpathian regions

Christian objects disappeared in Transylvania after the 7th century.[110] Most local cemeteries had cremation graves by this point,[111] but inhumation graves with west–east orientation from the late 9th or early 10th century were found at Ciumbrud and Orăștie.[112] The territory was invaded by the Hungarians around 896.[113]

The second-in-command of the Hungarian tribal federation, known as the gyula, converted to Christianity in Constantinople around 952.[116][117] The gyula was accompanied back to Hungary by the Greek Hierotheos, who was the bishop of Tourkia (Hungary) appointed by the Ecumenical Patriarch.[116][117] Pectoral crosses of Byzantine origin from this period have been found at the confluence of the Mureș and Tisa Rivers.[118] A bronze cross from Alba Iulia, and a Byzantine pectoral cross from Dăbâca from the 10th century have been found in Transylvania.[110] Additionally, a Greek monastery was founded at Cenad by a chieftain named Achtum who was baptized according to the Greek rite around 1002.[119][120]

Gyula's territory was incorporated with Achtum's territory into the Kingdom of Hungary under Stephen I, who was baptized according to the Latin rite.[121] Stephen I introduced the tithe, a church tax assessed on agricultural products.[122][123] Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Alba Iulia, Roman Catholic Diocese of Szeged–Csanád, and Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea Mare were the first three Roman Catholic dioceses in Romania and all became suffragans of the archbishop of Kalocsa in Hungary.[124] The provostship of Sibiu was transferred, upon the local Saxons's request, under the jurisdiction of the archbishop of Esztergom (Hungary) in 1212.[125]

Large cemeteries developed around churches after church officials insisted on churchyard burials.[126][127] The first Benedictine monastery in Transylvania was founded at Cluj-Manăștur in the second half of the 11th century.[128] New monasteries were established during the next few centuries in Almașu, Herina, Mănăstireni, and Meseș.[129][130] When the Cistercian abbey at Cârța was founded in the early 13th century, its estates were created on land belonging to the Vlachs.[129] The enmity between the Eastern and Western Churches also increased during the 11th century.[131]

Middle Ages

Orthodox Church in the intra-Carpathian regions

Although the Council of Buda prohibited the Eastern schism from erecting churches in 1279, numerous Orthodox churches were built in the period starting in the late 13th century.[133][134][135] These churches were mainly made of wood, though some landowners erected stone churches on their estates.[133] Most of these churches were built on the plan of a Greek cross. Some churches also display elements of Romanesque or Gothic architecture.[133][135] Many churches were painted with votive portraits illustrating the church founders.[135]

.JPG.webp)

Local Orthodox hierarchies were often under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Sees of Wallachia and Moldavia by the late 14th century.[137] For instance, the Metropolitan of Wallachia also styled himself "Exarch of all Hungary and the borderlands" in 1401.[137][138] Orthodox monasteries in Romania, including Șcheii Brașovului, were centers of Slavonic writing.[139] The Bible was first translated into Romanian by monks in Maramureș during the 15th century.[140]

Treatment of Orthodox Christians worsened under Louis I of Hungary, who ordered the arrest of Eastern Orthodox priests in Cuvin and Caraș in 1366.[141] He also decreed that only those who "loyally follow the faith of the Roman Church may keep and own properties" in Hațeg, Caransebeș, and Mehadia.[142] However, conversion was infrequent in this period; the Franciscan Bartholomew of Alverna complained in 1379 that "some stupid and indifferent people" disapprove of the conversion of "the Slavs and Romanians".[143] Both Romanians and Catholic landowners objected to this command.[143][144] Romanian chapels and stone churches built on the estates of Catholic noblemen and bishops were frequently mentioned in documents from the late 14th century.[133]

A special inquisitor sent against the Hussites by the pope also took forcible measures against "schismatics" in 1436.[145] Following the union of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches at the Council of Florence in 1439, the local Romanian Church was considered to be united with Rome.[146][147] Those who opposed the Church union, such as John of Caffa, were imprisoned.[137]

Although the monarchs only insisted on the conversion of the Romanians living in the southern borderlands, many Romanian noblemen converted to Catholicism in the 15th century.[143][148] Transylvanian authorities made systematic efforts to convert Romanians to Calvinism in the second half of the 16th century,[149] and the expulsion of priests who did not convert to the "true faith" was ordered in 1566.[150] Orthodox hierarchy was only restored under Stephen Báthory with the appointment of the Moldavian monk, Eftimie, as Orthodox bishop in 1571.[150][151]

Orthodox Church in Moldavia and Wallachia

An unknown Italian geographer wrongly described the "Romanians and the Vlachs" as pagans in the early 14th century.[153] For instance, Basarab I (c. 1310–1352), the Romanian ruler who achieved the independence of Wallachia in the territories between the Carpathians and the Lower Danube, was mentioned as "schismatic" by a royal diploma of 1332, referring to the Orthodox Church.[154][155] The Metropolitan See of Wallachia was established in 1359[156] when the Ecumenical Patriarch assigned Hyakinthos, the last metropolitan of Vicina, to lead the local Orthodox Church.[157] Although a second Metropolitan See, with jurisdiction over Oltenia, was set up in Severin (now Drobeta-Turnu Severin) in 1370, there was again only one Metropolitan in the principality after around 1403.[157][158][159] The local Church was reorganized under Radu IV the Great (1496–1508) by Patriarch Nephon II of Constantinople, the former Ecumenical Patriarch who founded two suffragan bishoprics.[158][160]

A second principality, Moldavia, achieved its independence in the territories to the east of the Carpathians under Bogdan I (1359 – c. 1365), but it still remained under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox hierarch of Halych (Ukraine).[161][162] Although the metropolitan of Halych consecrated two bishops for Moldavia in 1386, the Ecumenical Patriarch objected to this.[163] The patriarch established a separate metropolitan see for Moldavia in 1394, but his appointee was refused by Stephen I of Moldavia (1394–1399).[158][163] The conflict was solved when the patriarch recognized a member of the princely family as metropolitan in 1401.[164] In Moldavia, two suffragan bishoprics in Roman, and Rădăuți were first recorded in 1408 and 1471.[158][160]

From the second half of the 14th century, Romanian princes sponsored the monasteries of Mount Athos (Greece).[166] First, the Koutloumousiou monastery received donations from Nicholas Alexander of Wallachia (1352–1364).[167] In Wallachia, the monastery at Vodița was established in 1372 by the monk Nicodemus from Serbia, who had embraced monastic life at Chilandar on Mount Athos.[147][168] Monks fleeing from the Ottomans founded the earliest monastery in Moldavia at Neamț in 1407.[169][170] From the 15th century the four Eastern patriarchs and several monastic institutions in the Ottoman Empire also received landed properties and other sources of income, such as mills, in the two principalities.[166]

Many monasteries, such as Cozia in Wallachia, and Bistrița in Moldavia, became important centers of Slavonic literature.[171] The earliest local chronicles, such as the "Chronicle of Putna", were also written by monks.[172] Religious books in Old Church Slavonic were printed in Târgoviște under the auspices of the monk Macaria from Montenegro after 1508.[173][174] Wallachia in particular became a leading center of the Orthodox world, which was demonstrated by the consecration of the cathedral of Curtea de Argeș in 1517 in the presence of the Ecumenical Patriarch and the Protos of Mount Athos.[175][176] The painted monasteries of Moldavia are still an important symbol of cultural heritage today.[177][178]

The extensive lands owned by monasteries made the monasteries a significant political and economic force.[179] Many of these monasteries also owned Gypsy and Tatar slaves.[180] Monastic institutions enjoyed fiscal privileges, including an exemption from taxes, although 16th-century monarchs occasionally tried to seize monastic assets.[181]

Wallachia and Moldavia maintained their autonomous status, though the princes were obliged to pay a yearly tax to the sultans starting during the 15th century.[182] Dobruja was annexed in 1417 by the Ottoman Empire, and the Ottomans also occupied parts of southern Moldavia in 1484, and Proilavia (now Brăila) in 1540.[182][183] These territories were under the jurisdiction of the metropolitans of Dristra and Proilavia for several centuries following the annexation.[158]

Other denominations

The Diocese of Cumania was destroyed during the Mongol invasion of 1241–1242.[109][185] After this, Catholic missions to the East were carried on by the Franciscans.[185] For example, Pope Nicholas IV sent Franciscan missionaries to the "country of the Vlachs" in 1288.[186] In the 14th and 15th centuries new Catholic dioceses were established in the territories to the east and south of the Carpathians, mainly due to the presence of Hungarian and Saxon colonists.[187] Local Romanians also sent a complaint to the Holy See in 1374 demanding a Romanian-speaking bishop.[188] Alexander the Good of Moldavia (1400–1432) also founded an Armenian bishopric in Suceava in 1401.[160][189] In Moldavia, however, many Catholic believers were forced to convert to Orthodoxy under Ștefan VI Rareș (1551–1552) and Alexandru Lăpușneanu (1552–1561).[190]

In the Kingdom of Hungary parish organization became fully developed in the 14th to 15th centuries.[191] In the 1330s, according to a papal tithe-register, the average ratio of villages with Catholic parishes was around forty percent in the entire kingdom, but in the territory of modern Romania there was a Catholic church in 954 settlements out of 2100 and 2200 settlements.[192][193] The institutional and economic power of the Catholic Church in Transylvania was systematically dismantled by the authorities in the second half of the 16th century.[194][195] The extensive lands of the bishopric of Transylvania were confiscated in 1542.[196][197] The Catholic Church soon became deprived of its own higher local hierarchy and subordinate to a state governed by Protestant monarchs and Estates.[194][198] Some of the local noblemen, including a branch of the powerful Báthory family and many Székelys, remained Catholics.[199]

Reformation

First the Hussite movement for religious reform began in Transylvania in the 1430s.[200][201] Many of the Hussites moved to Moldavia, the only state in Europe outside Bohemia where they remained free of persecution.[145][160]

The earliest evidence that Lutheran teachings "were known and followed" in Transylvania is a royal letter written to the town council of Sibiu in 1524.[202] The Transylvanian Saxons' assembly decreed the adoption of the Lutheran creed by all the Saxon towns in 1544.[203] Municipal authorities also tried to influence the ritual of the Orthodox services.[204] A Romanian Catechism was published in 1543, and a Romanian translation of the four Gospels in 1560.[205][206]

Calvinist preachers first became active in Oradea in the early 1550s.[207] The Diet recognized the existence of two distinct Protestant churches in 1564 after the Saxon and Hungarian clergy had failed to agree on the contested points of theology, such as the nature of communion services.[208][209] The government also exerted pressure on the Romanians in order to change their faith.[147] The Diet of 1566 decreed that a Romanian Calvinist bishop, Gheorghe of Sîngeorgiu, be their sole religious leader.[150]

A faction of Hungarian preachers raised doubts over the doctrine of the Trinity in the 1560s.[208] In a decade Cluj became the center of the Unitarian movement.[210][211][212] The four "received religions" was recognized in 1568 by the Diet of Turda which also gave ministers the right to teach according to their own understanding of Christianity.[213] Although a ban on further religious innovation was enacted in 1572, many Székelys turned to Sabbatarianism in the 1580s.[214]

The process of giving up pre-Reformation traditions was extremely slow in Transylvania.[215] Although all or some of the images were eliminated in the churches, sacred vessels were kept.[215] Protestant denominations also kept the strict observance of holidays and fasting periods.[216]

Early Modern and Modern Times

Orthodox Church in Moldavia, Wallachia, and Romania

The use of Romanian in church service was first introduced in Wallachia under Matei Basarab (1632–1654), and in Moldavia under Vasile Lupu (1634–1652).[217] During Vasile Lupu's reign a pan-Orthodox synod adopted the "Orthodox Confession of Faith" in Iași in 1642 in order to reject any Calvinist influence over Orthodox hierarchy.[218][219] The first complete Romanian "Book of Prayer" was published in 1679 by Metropolitan Dosoftei of Moldavia (1670–1686).[217][220] A team of scholars also completed the Romanian translation of the Bible in 1688.[220][221]

The two principalities suffered the highest degree of Ottoman exploitation during the "Phanariot century" (1711–1821) when princes appointed by the sultans ruled in both of them.[222] The second half of the 18th century, brought a spiritual renaissance, initiated by Paisius Velichkovsky.[223] His influence led to a resurgence of Hesychastic prayer in the monasteries in Moldavia.[224] In this period Romanian theological culture benefited from new translations from patristic literature.[225] In the first decades of the 19th century theological seminaries were established in both principalities, such as in the Socola Monastery in 1803, and in Bucharest in 1836.[225]

A new archbishopric subordinated to the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church was created in Chișinău when the Russian Empire annexed Bessarabia in 1812.[226] The Russian authorities soon forbade its archbishop from having any connections with the Orthodox Church in the Romanian principalities.[226]

Romanian society embarked upon a rapid development following the reinstallation of native princes in 1821.[227][228] For instance, the Gypsy slaves owned by the monasteries were freed in Moldavia in 1844, and in Wallachia in 1847.[229] The two principalities were united under Alexandru Ioan Cuza (1859–1866), and the new state adopted the name of Romania in 1862.[230] In his reign, the estates of the monasteries were nationalized.[231][232][233] He also endorsed the use of Romanian in the liturgy, and replaced the Cyrillic alphabet with the Romanian alphabet.[234] In 1860, the first Faculty of Orthodox Theology was founded at the University of Iași.[235]

The Orthodox churches of the former principalities, the Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia and the Metropolitan of Moldavia, merged to form the Romanian Orthodox Church. In 1864, the Romanian Orthodox Church was proclaimed independent, but the Ecumenical Patriarch pronounced the new ecclesiastic regime contrary to the holy canons.[226][237] Henceforth all ecclesiastic appointments and decisions were subject to state approval.[237] The Metropolitan of Wallachia, who received the title of Primate Metropolitan in 1865, became the head of the General Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church.[226] The 1866 Constitution of Romania recognized the Orthodox Church as the dominant religion in the kingdom.[234] A law passed in 1872 declared the church to be "autocephalous". After a long period of negotiations with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the latter finally recognized the Metropolis of Romania in 1885.

Following the Romanian War of Independence, Dobruja was awarded to Romania in 1878.[238] At that time the majority of Dobruja's population was Muslim, but a massive colonization effort soon began.[239] The region had also been inhabited from the late 17th century by a group of Russian Old Believers called Lipovans.[240]

The Great Powers recognized Romania's independence in 1880, after Romania's constitution was modified to allow the naturalization of non-Christians.[238][241] In order to solemnize Romania's independence, in 1882 the Orthodox hierarchy performed the ceremony of blessing the holy oil, a privilege that had thereto been reserved for the ecumenical patriarchs.[237] The new conflict with the patriarch delayed the canonical recognition of the autocephaly of the Romanian Orthodox Church for three years, until 1885.[226][242]

Orthodox Church in Transylvania and the Habsburg Empire

The 16th-century Calvinist princes of Transylvania insisted on the Orthodox clergy's unconditional subordination to the Calvinist superintendents.[244] For instance, when an Orthodox synod adopted measures for regulation of church life Gabriel Bethlen (1613–1630) removed the local metropolitan.[245] By forcing the use of Romanian instead of Old Church Slavonic in the liturgy, the authorities also contributed to the development of the Romanians' national consciousness.[219][246] Local Orthodox believers remained without their own religious leader after the integration of Transylvania into the Habsburg Empire, when a synod led by the metropolitan declared the union with Rome in 1698.[227][247]

The first movement for the reestablishment of the Orthodox Church was initiated in 1744 by Visarion Sarai, a Serbian monk.[248] The monk Sofronie organized Romanian peasants to demand a Serbian Orthodox bishop in 1759–1760.[249] In 1761 the government consented to the establishment of an Orthodox diocese in Sibiu under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Metropolitan of Sremski Karlovci.[227][250][251] The Serbian Metropolitan was also granted authority, in 1781, over the diocese of Cernăuți (now Chernivtsi, Ukraine) in Bukovina that had been annexed from Moldavia by the Habsburg Empire.[252]

In 1848 Andrei Șaguna became the bishop of Sibiu and worked to free the local Orthodox Church from the control of the Serbian Metropolitan.[225][243] He succeeded in 1864, when a separate Orthodox Church with its Metropolitan See in Sibiu was established with the consent of the government.[252][253] In the second half of the 19th century, the local Romanian Orthodox Church supervised the activity of four high schools, and over 2,700 elementary schools.[225] The Orthodox Church in Bukovina also became independent of the Serbian Metropolitan in 1873.[252] A Faculty of Orthodox Theology was founded in the University of Cernăuți in 1875.[225] However, many Romanian priests were deported or imprisoned for propagating the union of the lands inhabited by Romanians after Romania declared war on Austria–Hungary in 1916.[233][254]

Romanian Church united with Rome

After the Principality of Transylvania was annexed by the Habsburg Empire, the new Catholic rulers tried to attract the Romanians' support in order to strengthen their control over the principality governed by predominantly Protestant Estates.[255] For the Romanians, the Church Union proposed by the imperial court nurtured the hope that the central government would assist them in their conflicts with local authorities.[256]

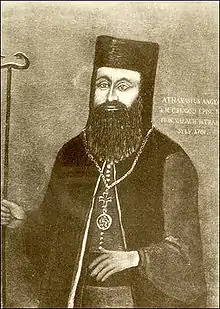

The union of the local Romanian Orthodox Church with Rome was declared in Alba Iulia, after years of negotiations, in 1698 by Metropolitan Atanasie Anghel and thirty-eight archpriests.[257] This union was based on the four points adopted by the Council of Florence, including the recognition of papal primacy.[257][258][259] Atanasie Anghel lost his title of metropolitan and was re-ordained as a bishop subordinated to the archbishop of Esztergom in 1701.[227][260]

The Orthodox world considered the union with Rome as apostasy.[261] Metropolitan Theodosie of Wallachia referred to Atanasie Anghel as "the new Judas".[261] Since many of the local Romanians opposed the Church union, it also created discord among them.[227][261]

Uniate Romanians assumed a leading role in the struggle for the Romanians' political emancipation in Transylvania for the next century.[262] Bishop Inocențiu Micu-Klein demanded in dozens of memoranda their recognition as the fourth "political nation" in the province.[263][264] The Uniate bishopric in Transylvania was raised to the rank of a Metropolitan See and became independent of the archbishop of Esztergom in 1855.[265][266]

Other denominations

Calvinism was popular in Transylvania during the 17th century.[267] Over sixty Unitarian ministers were expelled from their parishes in the Székely Land in the 1620s due to the influence of Calvinist Church leaders.[268][269] Although Transylanian Diets also enacted anti-Sabbatarian decrees, Sabbatarian communities survived in some Székely villages, such as Bezid.[270]

The Saxon communities' religious life was characterized by both differentiation from Calvinism, and by an increased number of worship services.[272] Traditional Lutheranism, due to its concern for individual spiritual needs, always remained more popular than Crypto-Calvinism.[273] The assets of the local Catholic Church were administered by the "Catholic Estates", a public body consisting of both laymen and priests.[274][275] A report on church visitations conducted around 1638 revealed that there were numerous Catholic villages without clergymen in the Székely Land.[276] Catholicism also almost disappeared in Moldavia in the 17th century.[277]

The Principality of Transylvania, following its integration into the Habsburg Empire, was administered according to the principles established by the Leopoldine Diploma of 1690, which confirmed the privileged status of the four "received religions".[278] In practice the new regime gave preference to the Roman Catholic Church.[279] Between 1711 and 1750, the apogee of the Counter-Reformation, the government ensured that Catholics would get preference in appointments to high offices.[279] The preeminent status of the Roman Catholic Church was not weakened under Joseph II (1780–1790), despite his issuance of the 1781 Edict of Tolerance.[280] Catholics who wished to convert to any of the other three "received religions" were still required to undergo an instruction.[280] The equal status of the Churches was not declared until the union of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1868.[281]

In the Kingdom of Romania, a new Roman Catholic archbishopric was organized in 1883 with its See in Bucharest.[282][283] Among the new Protestant movements, the first Baptist congregation was formed in 1856, and the Seventh-day Adventists were first introduced in Pitești in 1870.[284]

Greater Romania

Following World War I, ethnic Romanians in Banat, Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transylvania voted for the union with the Kingdom of Romania.[233][254] The new borders were recognized by international treaties in 1919–1920.[233][254] Thus, a Romania that had thereto been a relatively homogeneous state now included a mixed religious and ethnic population.[234] According to the 1930 census, 72 percent of its citizens were Orthodox, 7.9 percent Greek Catholic, 6.8 percent Lutheran, 3.9 percent Roman Catholic, and 2 percent Reformed.[286][287]

The constitution adopted in 1923 declared that "differences of religious beliefs and denominations" do not constitute "an impediment either to the acquisition of political rights or to the free exercise thereof".[288] It also recognized two national churches by declaring the Romanian Orthodox Church as the dominant denomination and by according the Romanian Church united with Rome "priority over other denominations".[289] The 1928 Law of Cults granted a fully recognized status to seven more denominations, among them the Roman Catholic, the Armenian, the Reformed, the Lutheran, and the Unitarian Churches.[290]

All Orthodox hierarchs in the enlarged kingdom became members of the Holy Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church in 1919.[286] New Orthodox bishoprics were set up, for instance, in Oradea, Cluj, Hotin (now Khotyn, Ukraine), and Timișoara.[286] The head of the church was raised to the rank of patriarch in 1925.[286][291] Orthodox ecclesiastical art flourished in this period due to the erection of new Orthodox churches especially in the towns of Transylvania.[292] The 1920s also witnessed the emergence of Orthodox revival movements, among them the "Lord's Army" founded in 1923 by Iosif Trifa.[293] Conservative Orthodox groups who refused to use the Gregorian calendar adopted by the Romanian Orthodox Church in 1925 formed the separate Old Calendar Romanian Orthodox Church.[294]

In this period, the preservation of ethnic minorities' cultural heritage became a primary responsibility of the traditional Protestant denominations.[295] The Reformed Church became closely identified with a large segment of the local Hungarian community, and the Lutheran Church perceived itself as the bearer of Transylvanian Saxon culture.[295] Among the new Protestant denominations, the Pentecostal movement was declared illegal in 1923.[296] The intense hostility between the Baptist and Orthodox communities also culminated in the temporary closing of all Baptist churches in 1938.[297]

Communist regime

According to the armistice signed between Romania and the Allied Powers in 1944, Romania lost Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union.[292] Consequently, the Orthodox dioceses in these territories were subordinated to the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.[298] In Romania, the Communist Party used the same tactics as in other Eastern European countries.[299] The Communist Party supported a coalition government, but in short time drove out all other parties from power.[299]

The 1948 Law on Religious Denominations formally upheld freedom of religion, but ambiguous stipulations obliged both priests and believers to conform to the constitution, national security, public order, and accepted morality.[300] For example, priests who voiced anti-communist attitudes could be deprived of their state-sponsored salaries.[300] The new law acknowledged fourteen denominations, among them the Old Rite Christian, Baptist, Adventist, and Pentecostal churches, but the Romanian Church united with Rome was abolished.[298][301]

Although the Orthodox church was completely subordinated to the state through the appointment of patriarchs sympathetic to the Communists, over 1,700 Orthodox priests of the 9,000 Orthodox priests in Romania were arrested between 1945 and 1964.[298][302] The Orthodox theologian Dumitru Stăniloae whose three-volume Dogmatic Theology presents a synthesis of patristic and contemporary themes was imprisoned between 1958 and 1964.[303] The first Romanian saints were also canonized between 1950 and 1955.[304] Among them, the 17th-century Sava Brancovici was canonized for his relations with Russia.[304]

Some other denominations met an even more tragic fate.[302] For instance, four of the five arrested Uniate bishops died in prison.[302] Religious dissident movements became especially active between 1975 and 1983.[305] For instance, the Orthodox priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa spent sixteen years in prison and was later condemned to ten more because of his sermons on the relationship of atheism, faith, and Marxism.[305] The crisis that led to the regime's fall in 1989 also started with the staunch resistance of the Reformed pastor László Tőkés, whom the authorities wanted to silence.[306]

Romania since 1989

The Communist regime came to an abrupt end on 22 December 1989.[307] The poet Mircea Dinescu, who was the first to speak on liberated Romanian television, began his statement with the words: "God has returned his face toward Romania again".[307] The new constitution of Romania, adopted in 1992, guarantees the freedom of thought, opinion, and religious beliefs when manifested in a spirit of tolerance and mutual respect.[308][309] Eighteen groups are currently recognized as religious denominations in the country.[310] Over 350 other religious associations has also been registered, but they do not enjoy the right to build houses of worship or to perform rites of baptism, marriage, or burial.[310]

Since the fall of Communism, about fourteen new Orthodox theology faculties and seminaries have opened, Orthodox monasteries have been reopened, and even new monasteries have been founded, for example, in Recea.[311] The Holy Synod has canonized new saints, among them Stephen the Great of Moldavia (1457–1504), and declared the second Sunday after Pentecost the "Sunday of the Romanian Saints".[312]

The Greek Catholic hierarchy was fully restored in 1990.[313] The four Roman Catholic dioceses in Transylvania, composed primarily of Hungarian-speaking inhabitants, hoped to be united into a distinct ecclesiastical province, but only Alba Iulia was raised to an archbishopric and placed directly under the jurisdiction of the Holy See in 1992.[314] After the exodus of the Transylvanian Saxons to Germany, only 30,000 of the members of the German Lutheran Church remained in Romania by the end of 1991.[315] According to the 2002 census, 86.7 percent of Romania's total population was Orthodox, 4.7 percent Roman Catholic, 3.2 percent Reformed, 1.5 percent Pentecostal, 0.9 percent Greek Catholic, and 0.6 percent Baptist.[316]

Footnotes

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 20.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 98.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 28.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 88.

- MacKendrick 1975, pp. 23, 192.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 84–85, 201.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 85.

- Pop et al. 2005, pp. 173–175.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 94.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 187

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 103.

- Dan Gh. Teodor, "Creștinismul la est de Carpați", Iași, 1991

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 45.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 11.

- Spinei 2009, p. 269.

- H. Mihăescu (1979): La langue latine dans le sud-est de l'Europe, București, p. 227, nr. 206

- Constantin C. Petolescu (2010): "Dacia – Un mileniu de istorie", Ed. Academiei Române, p. 358; ISBN 978-973-27-1999-2

- "sant". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române. dex-online.ro. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "călugar". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române pe internet. dex-online.ro. 2004–2008. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- "Rusalie". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române pe internet. dex-online.ro. 2004–2008. Archived from the original on 2012-07-07. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- "grijanie". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române. dex-online.ro. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "slujba". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române. dex-online.ro. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "popa". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române. dex-online.ro. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "episcop". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române. dex-online.ro. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "mântuire". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române pe internet. dex-online.ro. 2004–2008. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- "pildă". Dicționar explicativ al limbii române pe internet. dex-online.ro. 2004–2008. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- Boia 2001, p. 11.

- Niculescu 2007, p. 151.

- Keul 1994, pp. 16, 23.

- Keul 1994, p. 17.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 189.

- Pop 1996, p. 39.

- Spinei 2009, p. 104.

- Schramm 1997, pp. 276–277, 333–335.

- Schramm 1997, pp. 337–338.

- Cunningham 1999, p. 100.

- Madgearu 2004, p. 41

- Zugravu 1995–1996, p. 165

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 186.

- MacKendrick 1975, p. 187.

- Pop et al. 2005, pp. 186–187.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 188.

- Zugravu 1995–1996, p. 165.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 115.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 188.

- MacKendrick 1995, pp. 172–174.

- MacKendrick 1975, pp. 165–166.

- Niculescu 2007, p. 152.

- Curta 2006, p. 48.

- Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, Book VI, Chapter XXI.

- Stephenson 2000, p. 64.

- MacKendrick 1995, pp. 166, 210, 220–222.

- Mircea Păcurariu, "Sfinți daco-români și români", Editura Mitropoliei Moldovei și Bucovinei, (Iași, 1994)

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 187.

- Pop et al. 2005, pp. 187–188.

- MacKendrick 1975, p. 192.

- Pop et al. 2006, pp. 188–189.

- Wolfram 1988, pp. 57, 401.

- Eutropius; Watson, John Selby (1853). "Abridgement of Roman History". Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum. www.forumromanum.org. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Todd 1992, p. 142.

- Wolfram 1988, p. 78.

- Wolfram 1988, pp. 76–78, 80.

- Todd 1992, p. 119.

- Durostorum, Auxentius; Marchand, Jim (2010). "Letter". Texts. www9.georgetown.edu (Georgetown University). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Wolfram 1988, pp. 81–82.

- Wolfram 1988, pp. 82, 96.

- Bóna, István (2001). "The Kingdom of the Gepids". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Mierow, Charles C. (1997-04-22). "The Origin and Deeds of the Goths by Jordanes". Texts for Ancient History Courses. people.ucalgary.ca (University of Calgary). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Bóna, István (2001). "Gepidic Kings in Transylvania". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Todd 1992, p. 223.

- Todd 1992, p. 221.

- Curta 2005, p. 188.

- Curta 2005, p. 191.

- Teodor 2005, pp. 239–241.

- Paliga, Sorin & Teodor, Eugen, Lingvistica si arheologia slavilor timpurii (Early Slavic linguistics and archeology), Cetatea de scaun, 2009,ISBN 9786065370043 pag. 248.

- Spinei 2009, p. 270.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 127.

- Spinei 2009, p. 271.

- Fiedler 2008, p. 158.

- Curta 2006, p. 186.

- Teodor, Dan, "Creștinismul la est de Carpați", Editura Mitropoliei Moldovei, Iași, 1991, p.207.

- Fine 1991, pp. 94, 99.

- Fine 1991, p. 117.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 159.

- Curta 2006, p. 168.

- Fine 1991, p. 128.

- Pop et al. 2006, pp. 136, 143.

- Stephenson 2000, pp. 51–53, 55.

- Fine 1991, p. 199.

- Stephenson 2000, pp. 64, 75.

- Stephenson 2000, p. 97.

- Curta 2006, p. 299.

- Shepard 2006, p. 25.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 339.

- Curta 2006, p. 357.

- Stephenson 2000, pp. 289–290.

- Curta 2006, pp. 358–359.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 170.

- Fine 1994, p. 56.

- Dobre 2009, pp. 20–21.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 54.

- Curta 2006, p. 406.

- Spinei 2009, pp. 153–154.

- Spinei 2009, p. 155.

- Makkai, László (2001). "The Cumanian Country and the Province of Severin". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Mărtinaș 1999, p. 34.

- Curta 2006, p. 408.

- Madgearu 2005, p. 141.

- Madgearu 2005, pp. 141–142.

- Fiedler 2008, p. 161.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 59.

- Makkai, László (2001). "The Romanesque Style in Transylvania". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- G. Mihăilă, "Studii de lingvistică și filologie", Editura Facla, Timișoara, 1981, p.10

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 147.

- Stephenson 2000, p. 40.

- Curta 2006, p. 190.

- Stephenson 2000, p. 65.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 148.

- Berend et al. 2007, pp. 331, 345.

- Berend et al. 2007, p. 351.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 167.

- Curta 2006, p. 432.

- Kristó 2003, pp. 123–124.

- Curta 2006, p. 351.

- Berend et al. 2007, pp. 333–334.

- Kristó 2003, p. 86.

- Curta 2006, p. 354.

- Makkai, László (2001). "Monastic and Mendicant Orders". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 161.

- "Situl Bisericii Sf. Nicolae din Densuș". National Archaeological Record of Romania (RAN). ran.cimec.ro. 2012-12-14. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Makkai, László (2001). "Romanian Greek-Orthodox Priests and Churches". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 207.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 288.

- Florin Dobrei, "Bisericile ortodoxe hunedorene", Ed. Eftimie Murgu, Reșița, 2011, pp. 70–78.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 284.

- Makkai, László (2001). "Orthodox Romanians and Their Church Hierarchy". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 289.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 66.

- Pop et al. 2005, pp. 277, 288.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 278.

- Makkai, László (2001). "Religious Culture of the Romanians". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 287.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 189.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 250.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 240.

- Makkai, László (2001). "Romanian Voivodes and Cnezes, Nobles and Villeins". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Keul 1994, p. 104.

- Keul 1994, p. 105.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 283.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 94.

- Spinei 2009, p. 179.

- Lambru, Steliu (2007-09-10). "The Cumans in Romania's History". Pro Memoria: The History of Romanians. www.rri.ro (Radio România Internațional). Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Treptow et al. 1997, pp. 65–67.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 152.

- Papadakis, Meyendorff 1994, p. 262.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 192.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 217.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 237.

- Treptow et al. 1997, pp. 71–72.

- Papadakis, Meyendorff 1994, p. 263.

- Papadakis, Meyendorff 1994, p. 264.

- Papadakis, Meyendorff 1994, pp. 265–266.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 124.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 195.

- Shepard 2006, p. 26.

- Papadakis, Meyendorff 1994, p. 272.

- Pop et al. 2006, pp. 240–241.

- Papadakis, Meyendorff 1994, p. 273.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 122.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 194.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 64.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 136.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 273.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 147.

- Treptow et al. 1997, pp. 69–70.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 68.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 92.

- Crowe 2007, p. 108.

- Pop et al. 2006, pp. 241, 279.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 191.

- Pop et al. 2006, pp. 283–284.

- Makkai, László (2001). "The Gothic and Renaissance Styles". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Dobre 2009, p. 28.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 197.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 198.

- Pop et al. 2005, pp. 284, 287.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 102.

- Pozsony 2002, p. 89.

- Berend et al. 2007, p. 356.

- Kristó 2003, p. 135.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 268.

- Keul 1994, p. 60.

- Murdock 2000, p. 14.

- Keul 1994, p. 61.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 233.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 281.

- Barta, Gábor (2001). "Society and Political Power". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Sedlar 1994, pp. 40–41.

- Makkai, László (2001). "The Hussite Movement and the Peasant Revolt". History of Transylvania, Volume I: From the Beginnings to 1606. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Keul 1994, p. 47.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 231.

- Keul 1994, p. 76.

- Keul 1994, pp. 76, 92.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 284.

- Keul 1994, pp. 94–96.

- Murdock 2000, p. 15.

- Keul 1994, p. 245.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 234.

- Keul 1994, p. 115.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 235.

- Murdock 2000, p. 16.

- Keul 1994, pp. 130, 248.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 253.

- Pop et al. 2009, p. 254.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 200.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 332.

- Murdock 2000, p. 135.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 386.

- Treptow et al. 1997, pp. 200–201.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 205.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 193.

- Binns 2002, pp. 130, 132.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 199.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 198.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 197.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 12.

- Crowe 2007, p. 115.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 13.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 292.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 150.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 200.

- Stan, Turcescu 2007, p. 20.

- Istoria creștinismului Archived 2013-12-27 at the Wayback Machine at historia.ro (in Romanian)

- Păcurariu 2007, pp. 199–200.

- Kitromilides 2006, p. 239.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. xxiii.

- Boia 2001, p. 141.

- Pope 1992, pp. 157–158.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 351.

- Kitromilides 2006, pp. 240–241.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 342.

- Keul 1994, p. 190.

- Keul 1994, p. 169.

- Keul 1994, pp. 169, 269.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 187.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 437.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 441.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 442.

- Magocsi 2002, pp. 116–117.

- Magocsi 2002, p. 117.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 179.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 15.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 186.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 88.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p.101.

- Treptow et al. 1997, pp. 186–187.

- Pop et al. 2006, p. 356.

- Pop et al. 2006, pp. 356–357.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 189.

- Treptow et al. 1997, pp. 188–189.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 90.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 133.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. 102.

- Szász, Zoltán (2001). "The Suppression of the Romanian National Initiatives". History of Transylvania, Volume III: From 1830 to 1919. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Keul 1994, p. 256.

- Keul 1994, p. 171.

- Murdock 2000, p. 122.

- Keul 1994, pp. 174, 222.

- "Unitarian Church, Cluj-Napoca, judetul Cluj". Visit. www.romguide.net (Romguide). 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Keul 1994, p. 233.

- Pop et al. 2009, pp. 251–252, 253.

- Keul 1994, p. 178.

- Pop et al. 2005, p. 252.

- Keul 1994, pp. 212–213.

- Mărtinaș 1999, pp. 36–38.

- Pop et al. 2009, pp. 354–355.

- Trócsányi, Zsolt (2001). "Counter-Reformation and Protestant Resistance". History of Transylvania, Volume II: From 1606 to 1830. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Trócsányi, Zsolt (2001). "Josephinist Policies Regarding the Churches, Education, and Censorship". History of Transylvania, Volume II: From 1606 to 1830. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Szász, Zoltán (2001). "Constitutionalism and Reunification". History of Transylvania, Volume III: From 1830 to 1919. mek.niif.hu (Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár). Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- "Istoria Arhidiecezei Romano-Catolice de București". Prezentara. www.arcb.ro (Arhidieceza Romano-Catolică de București). 2009-01-11. Archived from the original on 2011-02-22. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Pozsony 2002, p. 103.

- Pope 1992, pp. 177, 186.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, pp. 63–64, 135.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 201.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 189.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 403.

- Stan, Turcescu 2007, p. 44.

- Pope 1992, p. 157.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 404.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 202.

- Pope 1992, p. 139.

- Binns 2002, pp. 26, 85.

- Pope 1992, p. 160.

- Pope 1992, pp. 183–184.

- Pope 1992, p. 177.

- Păcurariu 2007, p. 203.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 224.

- Stan, Turcescu 2007, p. 22.

- Treptow et al. 1997, p. 523.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 236.

- Binns 2002, pp. 92–93.

- Boia 2001, p. 73.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 264.

- Pope 1992, p. 148.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 279.

- Treptow, Popa 1996, p. xliii.

- Stan, Turcescu 2007, p. 27.

- Stan, Turcescu 2007, p. 28.

- Pacurariu 2007, p. 205.

- Stan, Turcescu 2007, p. 51.

- Magocsi 2002, p. 214.

- Magocsi 2002, p. 213.

- Pope 1992, pp. 200–201.

- Official site of the results of the 2002 Census (Report) (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 2009-07-06. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

References

- Berend, Nora; Laszlovszky, József; Szakács, Béla Zsolt (2007). The kingdom of Hungary. In: Berend, Nora (2007); Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus’, c. 900–1200; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2.

- Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66140-4.

- Boia, Lucian (2001). History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-96-2.

- Crowe, David M. (2007). A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8009-0.

- Cunningham, Mary B. (1999). The Orthodox Church in Byzantium. In: Hastings, Adrian (1999); A World History of Christianity; Cassell; ISBN 978-0-8028-4875-8.

- Curta, Florin (2005). Before Cyril and Methodius: Christianity and Barbarians beyond the Sixth- and Seventh-Century Danube Frontier. In: Curta, Florin (2005); East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages; The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Dobre, Claudia Florentina (2009). Mendicants in Moldavia: Mission in an Orthodox Land. AUREL Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938759-12-7.

- Fiedler, Uwe (2008). Bulgars in the Lower Danube Region: A Survey of the Archaeological Evidence and of the State of Current Research. In: Curta, Florin; Kovalev, Roman (2008); The Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars, and Cumans; Brill; ISBN 978-90-04-16389-8.

- Fine, John V. A., Jr. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08149-3.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-0511-2.

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M. (2006). The Legacy of the French Revolution: Orthodoxy and Nationalism. In: Angold, Michael (2006); The Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- Kristó, Gyula (2003). Early Transylvania (895–1324). Lucidus Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-9465-12-1.

- MacKendrick, Paul (1975). The Dacian Stones Speak. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1226-6.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2004). "The Spreading of Christianity in the rural areas of post-Roman Dacia (4th–7th centuries)" in Archaeus (2004), VIII, pp. 41–59.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005). The Romanians in the Anonymous Gesta Hungarorum: Truth and Fiction. Romanian Cultural Institute. ISBN 978-973-7784-01-8.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (2002). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98146-8.

- Mărtinaș, Dumitru (1999). The Origins of the Changos. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 978-973-98391-4-3.

- Murdock, Graeme (2000). Calvinism on the Frontier, 1600–1660: International Calvinism and the Reformed Church in Hungary and Transylvania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820859-4.

- Niculescu, Gheorghe Alexandru (2007). Archaeology and Nationalism in The History of the Romanians. In: Kohl, Philip L.; Kozelsky, Mara; Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (2007); Selective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National Pasts; The University of Chicago Press; ISBN 978-0-226-45058-2.

- Păcurariu, Mircea (2007). Romanian Christianity. In: Parry, Ken (2007); The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity; Blackwell Publishing; ISBN 978-0-631-23423-4.

- Papadakis, Aristeides; Meyendorff, John (1994). The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy: The Church 1071–1453 A.D. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-058-7.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Bărbulescu, Mihai; Dörner, Anton E.; Glodariu, Ioan; Pop, Grigor P.; Rotea, Mihai; Sălăgean, Tudor; Vasiliev, Valentin; Aldea, Bogdan; Proctor, Richard (2005). The History of Transylvania, Vol. I. (Until 1541). Romanian Cultural Institute. ISBN 978-973-7784-00-1.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (2006). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel(1996) "Românii și maghiarii în secolele IX-XIV. Geneza statului medieval în Transilvania." Centrul de studii transilvane. Fundația culturală română, Cluj-Napoca.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András; Andea, Susana; Costea, Ionuț; Dörner, Anton; Felezeu, Călin; Ghitta, Ovidiu; Kovács, András; Doru, Radoslav; Rüsz Fogarasi, Enikő; Szegedi, Edit (2009). The History of Transylvania, Vol. II. (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

- Pope, Earl A. (1992). Protestantism in Romania. In: Ramet, Sabrina Petra (1992); Protestantism and Politics in Eastern Europe and Russia: The Communist and Post-Communist Eras; Duke University Press; ISBN 978-0-8223-1241-3.

- Pozsony, Ferenc (2002). Church Life in Moldavian Hungarian Communities. In: Diószegi, László (2002); Hungarian Csángós in Moldavia: Essays on the Past and Present of the Hungarian Csángós in Moldavia; Teleki László Foundation – Pro Minoritate Foundation; ISBN 978-963-85774-4-3.

- Schramm, Gottfried (1997). Ein Damm bricht. Die römische Donaugrenze und die Invasionen des 5.–7. Jahrhunderts in Lichte der Namen und Wörter (A Dam Breaks: The Roman Danube frontier and the Invasions of the 5th–7th Centuries in the Light of Names and Words). R. Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 978-3-486-56262-0.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97290-9.

- Shepard, Jonathan (2006). The Byzantine Commonwealth 1000–1500. In: Angold, Michael (2006); The Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02756-4.

- Stan, Lavinia; Turcescu, Lucian (2007). Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530853-2.

- Teodor, Eugen S. (2005). The Shadow of a Frontier: The Wallachian Plain during the Justinian Age. In: Curta, Florin (2005); Borders, Barriers, and Ethnogenesis: Frontiers in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages; Brepols Publishers; ISBN 978-2-503-51529-8.

- Todd, Malcolm (1992). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1714-2.

- Treptow, Kurt W.; Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997). A History of Romania. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 978-973-98091-0-8.

- Treptow, Kurt W.; Popa, Marcel (1996). Historical Dictionary of Romania. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3179-7.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1988). History of the Goths. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06983-1.

- Zugravu, Nelu (1995–1996). "Cu privire la jurisdicția creștinilor nord-dunăreni în secolele II-VIII" in Pontica (1995–1996), XXVIII-XXIX, pp. 163–181.