History of Providence, Rhode Island

The Rhode Island city of Providence has a nearly 400-year history integral to that of the United States, including significance in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the American Revolutionary War by providing leadership and fighting strength, quartering troops, and supplying goods to residents by circumventing the blockade of Newport. The city is also noted for the first bloodshed of the American Revolution in the Gaspée Affair. Additionally, Providence is notable for economic shifts, moving from trading to manufacturing; the decline of manufacturing devastated the city during the Great Depression, but the city eventually attained economic recovery through investment of public funds.

Founding and colonial era

Providence was settled in June 1636 by Puritan theologian Roger Williams and grew into one of the original Thirteen Colonies. As a minister in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Williams had advocated for the Plymouth church's separation from the Church of England and condemned colonists' confiscation of land from Native Americans. For these "diverse, new, and dangerous opinions," he was convicted of sedition and heresy and banished from the colony. Williams and others established a settlement in Rumford, Rhode Island in 1636 on land given to them by the Wampanoag.[1][2] Soon after settling, the Plymouth Colony warned Williams that he had still not left the bounds of the colony. In response, the group moved down the Seekonk River, around the point now known as Fox Point and up the Providence River to the confluence of the a Moshassuck and Woonasquatucket Rivers. Here they established a new settlement they termed "Providence Plantations," cultivating the community as a refuge for religious dissenters.[3]

For the land, Williams reached a verbal agreement with the sachems Canonicus and Miantonomo—leaders of the indigenous Narragansett inhabitants. This agreement was later formalized in a deed dated March 24, 1638.[4]

Unlike Salem and Boston, Providence lacked a royal charter. The settlers thus organized themselves, allotting tracts on the eastern side of the Providence River in 1638. Roughly six acres each, these home lots extended from Towne Street (now South Main Street) up the cities eastern hill to Hope Street.[5] The portion of land between Towne Street and the eastern bank of the Providence River was held in common.[6]

The settlement lacked an official religion; no church building was erected in the town until the 18th century. In the absence of a church, the settlers congregated for religious and civil purposes on the common land adjacent to Roger Williams' home lot and later in the 1646 mill built by John Smith.[7]

Over the following two decades, Providence Plantations grew into a self sufficient agricultural and fishing settlement, though its lands were difficult to farm and its borders were disputed with Connecticut and Massachusetts.[8] During this period, the original temporary log dwellings built by the first settlers gave way to new clapboard stone-end houses with gabled roofs.[7]

An Indian coalition burned Providence to the ground on March 29, 1676, during King Philip's War, making it one of two major Colonial settlements burned.[9] The only two houses known to have survived the fire are the William Field House and Roger Mowry Tavern, both of which have since been demolished.[10]

After the town was rebuilt, the economy expanded into more industrial and commercial activity. The outer lands of Providence Plantation extending to the Massachusetts and Connecticut borders were incorporated as Scituate, Glocester, and Smithfield, Rhode Island, in 1731.[8] Later, Cranston, Johnston, and North Providence were also carved out of Providence's municipal territory.[8]

In 1700, the first church building was erected in the city—a Baptist church on the corner of Smith and North Main Streets.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade fueled the growth of the Providence economy, bringing the city to a position of economic prosperity by the mid-18th century. On voyages to plantations in the West Indies Providences merchants exchanged enslaved people as well as lumber and dairy for molasses. In 1755, enslaved people accounted for 8 percent of Providence's population.[11]

By the 1760s, the population of the city's urban core reached 4,000.[8]

In 1770, Brown University moved to Providence from nearby Warren. At the time, the college was known as Rhode Island College and occupied a single building on College Hill. The college's choice to relocate to Providence as opposed to Newport symbolized a larger shift away from the latter city's commercial and political dominance over the state.[12][13]

American Revolution

_2.jpg.webp)

In 1776, Providence recorded a population of 4,321.[14]

In the mid-1770s, the British government levied taxes that impeded Providence's maritime, fishing, and agricultural industries, the mainstays of the city's economy. One example was the Sugar Act, which affected Providence's distilleries and its trade in rum. These taxes caused the Colony of Rhode Island to join the other colonies in renouncing allegiance to the British Crown. Providence residents were among the first to spill blood in the American Revolution during the Gaspée Affair in 1772.[8]

Providence escaped British occupation during the American Revolutionary War. The British did, however, capture Newport imposing a blockade that devastated the city's economy and cemented Providence as Rhode Island's undisputed economic and urban center.

During the war American troops were quartered in Providence. Brown University's University Hall was used as a barracks and military hospital for American soldiers, while French troops were quartered in the city's Market House.[8][15]

Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries

Economic and demographic shifts

In the late 18th and early 19th century, the city became a center of the lucrative China Trade. Between 1789 and 1841 Providence was one of America's leading ports in the nation's direct trade with China. During this era, three of the seven US consuls to China came from Providence. Exchange with Canton and the East Indies benefited Providence merchants immensely. With their newly accrued wealth, many members of this merchant class constructed large mansions in College Hill; among these homes are the 1792 Nightingale–Brown House and Corliss–Carrington House (1812).[16] After 1830, Providence's trade shifted to Canada, which supplied the rapidly industrializing city with coal and lumber.[17]

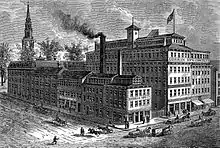

In the early 19th century, the economy began to shift from maritime endeavors to manufacturing—particularly machinery, tools, silverware, jewelry, and textiles. At one time, Providence boasted some of the largest manufacturing plants in the country, including Brown & Sharpe, Nicholson File, and Gorham Manufacturing Company.[8] The city's industries attracted many immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Sweden, England, Italy, Portugal, Cape Verde, and French Canada. Economic and demographic shifts caused social strife.[8] Hard Scrabble and Snow Town—two African American neighborhoods in the city—were the sites of race riots in 1824 and 1831.[18][19] Providence residents ratified a city charter in 1831 as the population passed 17,000.[8]

Seat of government

The seat of city government was located in the Market House from its incorporation as a city in 1832 until 1878.[20] Market House is located in Market Square, which was the geographic and social center of the city. The city offices quickly outgrew this building, and the City Council resolved to create a permanent municipal building in 1845.[20] The city spent the next 30 years searching for a suitable location, resulting in what one historian calls "Providence's Thirty Years War," as the council bickered over where to situate the new building.[20] The city offices moved into the Providence City Hall in 1878.

Jewelry industry

Seril Dodge and his nephew Nehemiah Dodge started the manufacture of jewelry in Providence in 1794, and jewelry was once the primary industry in Rhode Island.[21][22] The industry grew slowly during the early 19th century, then more rapidly.[23] Jewelry making and silverware attracted both American and foreign craftsmen to the city as the industry grew in prominence.[23] By 1850, there were 57 firms and 590 workers in the jewelry trade.[23] By 1880, Rhode Island led the United States in the manufacture of jewelry, accounting for more than one quarter of the entire national jewelry production.[23] By 1890, there were more than 200 firms with almost 7,000 workers in Providence.[22]

By the 1960s, jewelry trade magazines referred to Providence as “the jewelry capital of the world.”[22] The industry peaked in 1978 with 32,500 workers, then began a swift decline.[21] By 1996, the number of jewelry workers shrank to 13,500.[21] Numerous former factories were left vacant in the jewelry district, and many of them became offices, residences, restaurants, bars, and nightclubs.[21]

Late 19th Century

_(14778838484).jpg.webp)

Providence thrived in the late 1800s, with waves of immigrants bringing the population from 54,595 in 1865 to 175,597 by 1900.[8]

In 1871 Betsey Williams bequeathed 102 acres of land to the city for the development of Roger Williams Park. Designed by Horace Cleveland, the elaborately landscaped grounds were intended to serve as an escape for the workers of the industrial, urban center of Providence.[24]

By 1890, Providence's Union Railroad had a network which included over 300 horsecars and 1,515 horses.[25] Two years later, the first electric streetcars were introduced in Providence,[25] and the city soon had an electric streetcar network extending from Crescent Park to Pawtuxet in the south and Pawtucket in the north.[25] According to journalist Mike Stanton, "Providence was one of the richest cities in America in the early 1900s."[26]

However, increased population density brought public health problems when a cholera outbreak swept the city in 1854. A survey of living conditions conducted by the city discovered unhealthy crowding among immigrants and workers. In one case, 29 people were recorded as living in a single-story house; in another, 47 people shared a two-story home. The survey found 5,780 outhouses in the city, of which "fewer than half were emptied annually." Local cemeteries saw record numbers of burials. For the next 30 years, 1854 was remembered as "The Year of Cholera".[27]

Early 20th century

Influenza outbreak

In early September 1918, the first cases of the Spanish flu started appearing in Providence.[28] By the end of the month, public health superintendent Charles V. Chapin had identified over 2,500 cases in the city.[28] Chapin and other officials responded by ordering more hospital beds and increased staffing.[28] On October 6, the Providence Board of Health issued a general closure order, affecting all public and private schools, theaters, movie houses, and dance halls.[28] The spread of the influenza reached its highest level during October 3–9, with 6,700 cases reported.[28] The closure order was rescinded on October 25.[28] The flu returned for a smaller second wave in January 1919, which hit schools particularly hard.[28] By February 5, no new cases were being reported and the pandemic was declared over.[28]

Early decline

The city began to see a decline by the mid-1920s as industries shut down, notably textiles. The Great Depression hit the city hard, and Providence's downtown was flooded by the New England Hurricane of 1938 soon after. The city saw a further decline as a result of the nationwide trends with the construction of highways and increased suburbanization.[8]

Mid-late 20th century

Interstate highways

Starting in 1956, construction began on Interstate 195 and Interstate 95.[29][30] The routes of these highways takes them directly through several established Providence neighborhoods. Over the next several years hundreds of homes and businesses and two churches are demolished.[31] The highways disconnect Downtown from South Providence, the West End, Federal Hill, and Smith Hill neighborhoods, leaving the city forever divided.[31][29][30]

Decline of downtown

.jpg.webp)

Providence's population declined from a peak of 253,504 in 1940 to only 179,213 in 1970, as the white middle class fled to the suburbs.[31] Those who stayed behind were disproportionately poor and in need of social services.[31] Retail stores, movie theaters, and businesses likewise fled as Providence's downtown was widely considered polluted, dangerous to visit after dark, and lacked parking.[31] As hotels and department stores failed, many significant downtown buildings were demolished, boarded up or abandoned.[31] In 1964, Westminster Street was pedestrianized in a failed attempt to attract shoppers; within a decade, all the street's major stores had closed except Woolworth's; the street was de-pedestrianized in 1989.[31] Familiar local names like the Crown Hotel, Kent Hotel, Narragansett Hotel, Dreyfus Hotel, Arcadia Ballroom, Albee Theater, Port Arthur Chinese Restaurant, J.J. Newbury's, Kresge's, Gladdings, and Shepard's Department Store disappeared from the city by the end of the 1970s.[31]

Crime

From the 1950s to the 1980s, Providence was a notorious bastion of organized crime. Legendary mafia boss Raymond L.S. Patriarca ruled a vast criminal enterprise from the city for over three decades, during which murders and kidnappings became commonplace.[32]

"Renaissance City"

The city's experienced a sort of Renaissance in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as $606 million of local and national Community Development funds was invested throughout the city and the declining population began to stabilize. In the 1990s, Mayor Buddy Cianci showcased the city's strength in arts and pushed for further revitalization, ultimately resulting in opening up the city's rivers (which had been paved over), relocation of a large section of railroad underground, creation of Waterplace Park and river walks along the river's banks, and construction of the Fleet Skating Rink (now the Bank of America Skating Rink) in downtown and the 1.4 million ft2 Providence Place Mall.[8]

In 1980, the city's previously declining population began to grow once again.[33]

21st century

First decades

From the mid 2000s to early 2010s, the city of Providence worked to relocate a portions of Interstate 95 and 195, with the intention of reunifying formerly divided neighborhoods on the city's West Side. The project, which cost more than $620 million, freed 19 acres of land in and adjacent to the city's Jewelry District.[34] The city and state have marketed the new neighborhood as Providence's "Innovation & Design District," with the intention of establishing the area as a science, technology, and education hub.[35]

During the 2000s and 2010s, New investment was triggered within the city with new construction including numerous condominium and hotel projects and a new office highrise.[36][37] The city and recruited a number of companies including Virgin Pulse and GE Digital to establish offices in Providence, offering tax incentives and advertising a lower cost of living than nearby Boston.[38]

Ongoing challenges

Poverty, however, remains a problem, with 26 percent of the city living below the federal poverty line.[39] A 2020 Brandeis University report found that the opportunity gap between white and Latino children was the third-highest of the 100 cities considered in the study.[40]

From 2004 to 2005, Providence had the highest rise in median housing price of any city in the United States.[41]

Bicycle and pedestrian initiatives

The late 2010s saw a number of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure improvements, many spearheaded by Jorge Elorza, himself a cycling enthusiast.[42] A greenway opened in Roger Williams Park in 2017.[42] In August 2019, the Providence River Pedestrian and Bicycle Bridge, connecting the east and west sides of downtown, opened.[43] It was built on the granite piers of the old Route 195 bridge.[43] A bicycle sharing program started in September 2018, only to be halted within a year due to vandalism and theft.[44]

In January 2020, mayor Jorge Elorza unveiled a "Great Streets" initiative to create a framework of public space improvements to encourage walking, riding bicycles, and public transit.[45] The plan includes establishing an "Urban Trail Network" which includes 60 miles of bicycle paths, bike lanes, and greenways within Providence.[46]

See also

Notes

- "Three and One-Half Centuries at a Glance". City of Providence, Rhode Island. May 2002. Archived from the original on January 13, 2006. Retrieved January 17, 2006.

- "Roger Williams - Founder of Rhode Island & Salem Minister - HISTORY". www.history.com. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- "Rhode Island's Plymouth Rock—Well, Almost". New England Historical Society. March 20, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- "Educational Resources - Original Deed to Providence - Roger Williams Initiative". www.findingrogerwilliams.com. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- Providence, Mailing Address: 282 North Main Street; Us, RI 02903 Phone: 401-521-7266 Contact. "Roger Williams: In Providence - Roger Williams National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- Auwaerter, John Eric; Cowperthwaite, Karen (2010). Cultural Landscape Report for Roger Williams National Memorial: Providence, Rhode Island. Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service.

- Auwaerter, John Eric; Cowperthwaite, Karen (2010). Cultural Landscape Report for Roger Williams National Memorial: Providence, Rhode Island. Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service.

- "Three and One-Half Centuries at a Glance". City of Providence, Rhode Island. May 2002. Retrieved January 17, 2006.

- Lepore, xxvii.

- Witcher, Pheamo. A Study of the Providence Historic District Commission (Thesis). University of Rhode Island.

- Clark-Pujara, Christy (March 6, 2018). Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-5563-6.

- Withey, Lynne (January 1, 1984). Urban Growth in Colonial Rhode Island: Newport and Providence in the Eighteenth Century. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-751-9.

- FitzGerald, Frances. "Peculiar Institutions". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- Arnold, Samuel Greene (1874). History of the state of Rhode Island and Providence plantations. New York, etc.: D. Appleton & Co.

- Cady, John Hutchins (October 1952). "The Providence Market House and its neighborhood" (PDF). Rhode Island History. Rhode Island Historical Society. 11 (4): 97–106. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Johnston, Patricia; Frank, Caroline (November 4, 2014). Global Trade and Visual Arts in Federal New England. University of New Hampshire Press. ISBN 978-1-61168-585-5.

- www.rihs.org https://www.rihs.org/mssinv/MSS028sg1.htm. Retrieved October 22, 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Hardscrabble". Brown University. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- "Snow Town Riot". Brown University. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Campbell, Paul. "A Brief History of Providence City Hall". City Archives. City of Providence. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- Abbott, Elizabeth (January 26, 1997). "Providence Jewelry District Gets a New Luster". The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- Davis, Paul (July 4, 2015). "R.I.'s jewelry industry history in search of a permanent home". Providence: The Providence Journal. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

In 1794, Seril Dodge opened a jewelry store on North Main Street in Providence, and Nehemiah Dodge developed a process for coating lesser metals with gold and silver. Historians say that the two men started Rhode Island’s jewelry industry.

- "The History of the Jewelry District". Historic Jewelry District. Providence: The Jewelry District Association. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

In 1830, there were 27 jewelry firms employing 280 workers in Providence; by 1850, there were 57 firms and 590 workers.

- "The People's Park". Roger Williams Park. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Molloy, Scott (2007). Trolley Wars: Streetcar Workers on the Line. UPNE. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1584656302. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- Stanton, Mike (2003). The Prince of Providence. New York: Random House. p. 7. ISBN 0-375-75967-0.

- McKenna, Ray (April 19, 2020). "My Turn: Ray McKenna: R.I. residents of 1854 would relate". The Providence Journal. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Providence, Rhode Island". Influenza Encyclopedia. University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- "Interstate 95". Interstate Guide. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- "Interstate 195 Rhode Island / Massachusetts". Interstate Guide. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- Coren, Samuel (May 2, 2016). "Interface: Providence and the Populist Roots of a Downtown Revival". Journal of Planning History. 16 (1): 4–7. doi:10.1177/1538513216645620. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "CHAPTER ONE: DIVINE PROVIDENCE". CRIMETOWN. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- Leazes, Francis J.; Motte, Mark T. (2004). Providence, the Renaissance City. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-55553-604-6.

- Brown, Eliot (March 5, 2014). "Providence Reclaims a 'Link' to Its Past". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Abbott, Elizabeth (August 18, 2015). "Providence, R.I., Is Building on a Highway's Footprint (Published 2015)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Lynn Arditi. "Condo supplies risings as prices drop". projo.com. Providence Journal. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- Daniel Barbarisi. "Hunger for Hotels". projo.com. Providence Journal. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- D'Ambrosio, Daniel. "How Rhode Island Is Sparking Another Industrial Revolution". Forbes. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Providence city, Rhode Island". www.census.gov. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Borg, Linda. "Brandeis report: Opportunity gap among children of different races in Providence among nation's widest". providencejournal.com. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- "Money Magazine: Best Places to Live: Home Appreciation". cnnmoney.com. Cable News Network LP, LLLP. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- Curley, Bob (June 22, 2017). "Building a More Bikeable Providence". Rhody Beat. Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- List, Madeline (August 9, 2019). "$21.9 million later, pedestrian bridge opens in downtown Providence". The Providence Journal. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- Amaral, Brian (May 20, 2020). "Watchdog Team: Company behind Jump bikes was stunned by level of vandalism in Providence". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "City of Providence Unveils Final Great Streets Plan". City of Providence. City of Providence. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Providence Unveils Plan for 'Great Streets'". Eco RI News. January 29, 2020. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- 4. Three and One-Half Centuries at a Glance ProvidenceRI.com - History and Fact.

References

- Lepore, Jill. (1998). The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-375-70262-8.

Further reading

- The early records of the town of Providence, Internet Archive