Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies[2] or the Thirteen American Colonies,[3] were a group of colonies of Great Britain on the Atlantic coast of North America founded in the 17th and 18th centuries which declared independence in 1776 and formed the United States of America. The Thirteen Colonies had very similar political, constitutional, and legal systems, and were dominated by Protestant English-speakers. The New England colonies (Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New Hampshire), as well as the colonies of Maryland and Pennsylvania, were founded primarily for religious beliefs, while the other colonies were founded for business and economic expansion. All thirteen were part of Britain's possessions in the New World, which also included colonies in Canada, Florida, and the Caribbean.

Thirteen Colonies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1607–1776 | |||||||||||

Flag of British America (1707–1775) | |||||||||||

The Thirteen Colonies (shown in red) in 1775 | |||||||||||

| Status | Part of British America (1607–1776) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Administered from London, Great Britain | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Protestantism Roman Catholicism Judaism Native American religions | ||||||||||

| Government | Colonial Constitutional Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||

• 1607–1625 | James I & VI (first) | ||||||||||

• 1760–1776 | George III (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 1585 | |||||||||||

| 1607 | |||||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||||

| 1663 | |||||||||||

| 1667 | |||||||||||

| 1713 | |||||||||||

| 1732 | |||||||||||

| 1754–1763 | |||||||||||

| 1776 | |||||||||||

| 1783 | |||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1625[1] | 1,980 | ||||||||||

• 1775[1] | 2,400,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United States |

|

|

|

The colonial population grew from about 2,000 to 2.4 million between 1625 and 1775, displacing Native Americans. This population included people subject to a system of slavery which was legal in all of the colonies prior to the American Revolutionary War.[4] In the 18th century, the British government operated its colonies under a policy of mercantilism, in which the central government administered its possessions for the economic benefit of the mother country.

The Thirteen Colonies had a high degree of self-governance and active local elections, and they resisted London's demands for more control. The French and Indian War (1754–1763) against France and its Indian allies led to growing tensions between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies. During the 1750s, the colonies began collaborating with one another instead of dealing directly with Britain. These inter-colonial activities cultivated a sense of shared American identity and led to calls for protection of the colonists' "Rights as Englishmen", especially the principle of "no taxation without representation". Conflicts with the British government over taxes and rights led to the American Revolution, in which the colonies worked together to form the Continental Congress. The colonists fought the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) with the aid of the Kingdom of France and, to a much smaller degree, the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of Spain.[5] Just prior to declaring independence, the Thirteen Colonies consisted of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.[6]

British colonies

Dark Red = New England colonies.

Bright Red = Middle Atlantic colonies.

Red-brown = Southern colonies.

In 1606, King James I of England granted charters to both the Plymouth Company and the London Company for the purpose of establishing permanent settlements in America. The London Company established the Colony and Dominion of Virginia in 1607, the first permanently settled English colony on the continent. The Plymouth Company founded the Popham Colony on the Kennebec River, but it was short-lived. The Plymouth Council for New England sponsored several colonization projects, culminating with Plymouth Colony in 1620 which was settled by English Puritan separatists, known today as the Pilgrims.[7] The Dutch, Swedish, and French also established successful American colonies at roughly the same time as the English, but they eventually came under the English crown. The Thirteen Colonies were complete with the establishment of the Province of Georgia in 1732, although the term "Thirteen Colonies" became current only in the context of the American Revolution.[8]

In London beginning in 1660, all colonies were governed through a state department known as the Southern Department, and a committee of the Privy Council called the Board of Trade and Plantations. In 1768, a specific state department was created for America, but it was disbanded in 1782 when the Home Office took responsibility.[9]

New England colonies

1. Province of Massachusetts Bay, chartered as a royal colony in 1691

- Popham Colony, established in 1607; abandoned in 1608

- Plymouth Colony, established in 1620; merged with Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691

- Province of Maine, patent issued in 1622 by Council for New England; patent reissued by Charles I in 1639; absorbed by Massachusetts Bay Colony by 1658

- Massachusetts Bay Colony, established in 1629; merged with Plymouth Colony in 1691

2. Province of New Hampshire, established in 1629; merged with Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641; chartered as royal colony in 1679

3. Connecticut Colony, established in 1636; chartered as royal colony in 1662

- Saybrook Colony, established in 1635; merged with Connecticut Colony in 1644

- New Haven Colony, established in 1638; merged with Connecticut Colony in 1664

4. Colony of Rhode Island chartered as royal colony in 1663

- Providence Plantations established by Roger Williams in 1636

- Portsmouth established in 1638 by John Clarke, William Coddington, and others

- Newport established in 1639 after a disagreement and split among the settlers in Portsmouth

- Warwick established in 1642 by Samuel Gorton

- These four settlements merged into single Royal colony in 1663

Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and New Haven Colonies formed the New England Confederation in (1643–1654; 1675–c. 1680) and all New England colonies were included in the Dominion of New England (1686–1689).

Middle colonies

5. Delaware Colony (before 1776, the Lower Counties on Delaware), established in 1664 as proprietary colony

6. Province of New York, established as proprietary colony in 1664; chartered as royal colony in 1686; included in the Dominion of New England (1686–1689)

7. Province of New Jersey, established as proprietary colony in 1664; chartered as royal colony in 1702

- East Jersey, established in 1674; merged with West Jersey to re-form Province of New Jersey in 1702; included in the Dominion of New England

- West Jersey, established in 1674; merged with East Jersey to re-form Province of New Jersey in 1702; included in the Dominion of New England

8. Province of Pennsylvania, established in 1681 as proprietary colony

Southern colonies

9. Colony and Dominion of Virginia, established in 1607 as proprietary colony; chartered as royal colony in 1624

10. Province of Maryland, established 1632 as proprietary colony

– Province of Carolina, initial charter issued in 1629; initial settlements established after 1651; initial charter voided in 1660 by Charles II; rechartered as proprietary colony in 1663. (Earlier, along the coast, the Roanoke Colony was established in 1585; re-established in 1587; and found abandoned in 1590.) The Carolina province was divided into separate proprietary colonies, north and south in 1712.

11. Province of North Carolina, previously part of the Carolina province until 1712; chartered as royal colony in 1729.

12. Province of South Carolina, previously part of the Carolina province until 1712; chartered as royal colony in 1729

13. Province of Georgia, established as proprietary colony in 1732; royal colony from 1752.

17th century

Southern colonies

The first successful English colony was Jamestown, established May 14, 1607 near Chesapeake Bay. The business venture was financed and coordinated by the London Virginia Company, a joint stock company looking for gold. Its first years were extremely difficult, with very high death rates from disease and starvation, wars with local Native Americans, and little gold. The colony survived and flourished by turning to tobacco as a cash crop.[10][11]

In 1632, King Charles I granted the charter for Province of Maryland to Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore. Calvert's father had been a prominent Catholic official who encouraged Catholic immigration to the English colonies. The charter offered no guidelines on religion.[12]

The Province of Carolina was the second attempted English settlement south of Virginia, the first being the failed attempt at Roanoke. It was a private venture, financed by a group of English Lords Proprietors who obtained a Royal Charter to the Carolinas in 1663, hoping that a new colony in the south would become profitable like Jamestown. Carolina was not settled until 1670, and even then the first attempt failed because there was no incentive for emigration to that area. Eventually, however, the Lords combined their remaining capital and financed a settlement mission to the area led by Sir John Colleton. The expedition located fertile and defensible ground at what became Charleston, originally Charles Town for Charles II of England.[13]

Middle colonies

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders explored and established fur trading posts on the Hudson River, Delaware River, and Connecticut River, seeking to protect their interests in the fur trade. The Dutch West India Company established permanent settlements on the Hudson River, creating the Dutch colony of New Netherland. In 1626, Peter Minuit purchased the island of Manhattan from the Lenape Indians and established the outpost of New Amsterdam.[14] Relatively few Dutch settled in New Netherland, but the colony came to dominate the regional fur trade.[15] It also served as the base for extensive trade with the English colonies, and many products from New England and Virginia were carried to Europe on Dutch ships.[16] The Dutch also engaged in the burgeoning Atlantic slave trade, taking enslaved Africans to the English colonies in North America and Barbados.[17] The West India Company desired to grow New Netherland as it became commercially successful, yet the colony failed to attract the same level of settlement as the English colonies did. Many of those who did immigrate to the colony were English, German, Walloon, or Sephardim.[18]

In 1638, Sweden established the colony of New Sweden in the Delaware Valley. The operation was led by former members of the Dutch West India Company, including Peter Minuit.[19] New Sweden established extensive trading contacts with English colonies to the south, and shipped much of the tobacco produced in Virginia.[20] The colony was conquered by the Dutch in 1655,[21] while Sweden was engaged in the Second Northern War.

Beginning in the 1650s, the English and Dutch engaged in a series of wars, and the English sought to conquer New Netherland.[22] Richard Nicolls captured the lightly defended New Amsterdam in 1664, and his subordinates quickly captured the remainder of New Netherland.[23] The 1667 Treaty of Breda ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War and confirmed English control of the region.[24] The Dutch briefly regained control of parts of New Netherland in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, but surrendered claim to the territory in the 1674 Treaty of Westminster, ending the Dutch colonial presence in North America.[25]

After the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the British renamed the colony "York City" or "New York". Large numbers of Dutch remained in the colony, dominating the rural areas between New York City and Albany, while people from New England started moving in as well as immigrants from Germany. New York City attracted a large polyglot population, including a large black slave population.[26] In 1674, the proprietary colonies of East Jersey and West Jersey were created from lands formerly part of New York.[27]

Pennsylvania was founded in 1681 as a proprietary colony of Quaker William Penn. The main population elements included the Quaker population based in Philadelphia, a Scotch-Irish population on the Western frontier and numerous German colonies in between.[28] Philadelphia became the largest city in the colonies with its central location, excellent port, and a population of about 30,000.[29]

New England

The Pilgrims were a small group of Puritan separatists who felt that they needed to distance themselves physically from the Church of England, which they perceived as corrupted. They initially moved to the Netherlands, but eventually sailed to America in 1620 on the Mayflower. Upon their arrival, they drew up the Mayflower Compact, by which they bound themselves together as a united community, thus establishing the small Plymouth Colony. William Bradford was their main leader. After its founding, other settlers traveled from England to join the colony.[30]

More Puritans immigrated in 1629 and established the Massachusetts Bay Colony with 400 settlers. They sought to reform the Church of England by creating a new, ideologically pure church in the New World. By 1640, 20,000 had arrived; many died soon after arrival, but the others found a healthy climate and an ample food supply. The Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies together spawned other Puritan colonies in New England, including the New Haven, Saybrook, and Connecticut colonies. During the 17th century, the New Haven and Saybrook colonies were absorbed by Connecticut.[31]

Roger Williams established Providence Plantations in 1636 on land provided by Narragansett sachem Canonicus. Williams was a Puritan who preached religious tolerance, separation of Church and State, and a complete break with the Church of England. He was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony over theological disagreements; he founded the settlement based on an egalitarian constitution, providing for majority rule "in civil things" and "liberty of conscience" in religious matters.[32][33] In 1637, a second group including Anne Hutchinson established a second settlement on Aquidneck Island, also known as Rhode Island.

On October 19, 1652, the Massachusetts General Court decreed that "for the prevention of clipping of all such pieces of money as shall be coined with-in this jurisdiction, it is ordered by this Courte and the authorite thereof, that henceforth all pieces of money coined shall have a double ring on either side, with this inscription, Massachusetts, and a tree in the center on one side, and New England and the yeare of our Lord on the other side. "These coins were the famous "tree" pieces. There were Willow Tree Shillings, Oak Tree Shillings, and Pine Tree Shillings" minted by John Hull and Robert Sanderson in the "Hull Mint" on Summer Street in Boston, Massachusetts. "The Pine Tree was the last to be coined, and today there are specimens in existence, which is probably why all of these early coins are referred to as "the pine tree shillings." [34] The "Hull Mint" was forced to close in 1683. In 1684 the charter of Massachusetts was revoked by the king Charles II.

Other colonists settled to the north, mingling with adventurers and profit-oriented settlers to establish more religiously diverse colonies in New Hampshire and Maine. Massachusetts absorbed these small settlements when it made significant land claims in the 1640s and 1650s, but New Hampshire was eventually given a separate charter in 1679. Maine remained a part of Massachusetts until achieving statehood in 1820.

In 1685, King James II of England closed the legislatures and consolidated the New England colonies into the Dominion of New England, putting the region under control of Governor Edmund Andros. In 1688, the colonies of New York, West Jersey, and East Jersey were added to the dominion. Andros was overthrown and the dominion was closed in 1689, after the Glorious Revolution deposed King James II; the former colonies were re-established.[35] According to Guy Miller, the Rebellion of 1689 was the "climax of the 60-year-old struggle between the government in England and the Puritans of Massachusetts over the question of who was to rule the Bay colony."[36]

18th century

In 1702, East and West Jersey were combined to form the Province of New Jersey.

The northern and southern sections of the Carolina colony operated more or less independently until 1691 when Philip Ludwell was appointed governor of the entire province. From that time until 1708, the northern and southern settlements remained under one government. However, during this period, the two halves of the province began increasingly to be known as North Carolina and South Carolina, as the descendants of the colony's proprietors fought over the direction of the colony.[37] The colonists of Charles Town finally deposed their governor and elected their own government. This marked the start of separate governments in the Province of North-Carolina and the Province of South Carolina. In 1729, the king formally revoked Carolina's colonial charter and established both North Carolina and South Carolina as crown colonies.[38]

In the 1730s, Parliamentarian James Oglethorpe proposed that the area south of the Carolinas be colonized with the "worthy poor" of England to provide an alternative to the overcrowded debtors' prisons. Oglethorpe and other English philanthropists secured a royal charter as the Trustees of the colony of Georgia on June 9, 1732.[39] Oglethorpe and his compatriots hoped to establish a utopian colony that banned slavery and recruited only the most worthy settlers, but by 1750 the colony remained sparsely populated. The proprietors gave up their charter in 1752, at which point Georgia became a crown colony.[40]

The colonial population of Thirteen Colonies grew immensely in the 18th century. According to historian Alan Taylor, the population of the Thirteen Colonies stood at 1.5 million in 1750, which represented four-fifths of the population of British North America.[41] More than 90 percent of the colonists lived as farmers, though some seaports also flourished. In 1760, the cities of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston had a population in excess of 16,000, which was small by European standards.[42] By 1770, the economic output of the Thirteen Colonies made up forty percent of the gross domestic product of the British Empire.[43]

As the 18th century progressed, colonists began to settle far from the Atlantic coast. Pennsylvania, Virginia, Connecticut, and Maryland all laid claim to the land in the Ohio River valley. The colonies engaged in a scramble to purchase land from Indian tribes, as the British insisted that claims to land should rest on legitimate purchases.[44] Virginia was particularly intent on western expansion, and most of the elite Virginia families invested in the Ohio Company to promote the settlement of Ohio Country.[45]

Global trade and immigration

The British colonies in North America became part of the global British trading network, as the value tripled for exports from British North America to Britain between 1700 and 1754. The colonists were restricted in trading with other European powers, but they found profitable trade partners in the other British colonies, particularly in the Caribbean. The colonists traded foodstuffs, wood, tobacco, and various other resources for Asian tea, West Indian coffee, and West Indian sugar, among other items.[46] American Indians far from the Atlantic coast supplied the Atlantic market with beaver fur and deerskins.[47] British North America had an advantage in natural resources and established its own thriving shipbuilding industry, and many North American merchants engaged in the transatlantic trade.[48]

Improved economic conditions and easing of religious persecution in Europe made it more difficult to recruit labor to the colonies, and many colonies became increasingly reliant on slave labor, particularly in the South. The population of slaves in British North America grew dramatically between 1680 and 1750, and the growth was driven by a mixture of forced immigration and the reproduction of slaves.[49] Slaves supported vast plantation economies in the South, while slaves in the North worked in a variety of occupations.[50] There were some slave revolts, such as the Stono Rebellion and the New York Conspiracy of 1741, but these uprisings were suppressed.[51]

A small proportion of the English population migrated to British North America after 1700, but the colonies attracted new immigrants from other European countries. These immigrants traveled to all of the colonies, but the Middle Colonies attracted the most and continued to be more ethnically diverse than the other colonies.[52] Numerous settlers immigrated from Ireland,[53] both Catholic and Protestant—particularly "New Light" Ulster Presbyterians.[54] Protestant Germans also migrated in large numbers, particularly to Pennsylvania.[55] In the 1740s, the Thirteen Colonies underwent the First Great Awakening.[56]

French and Indian War

In 1738, an incident involving a Welsh mariner named Robert Jenkins sparked the War of Jenkins' Ear between Britain and Spain. Hundreds of North Americans volunteered for Admiral Edward Vernon's assault on Cartagena de Indias, a Spanish city in South America.[57] The war against Spain merged into a broader conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession, but most colonists called it King George's War.[58] In 1745, British and colonial forces captured the town of Louisbourg, and the war came to an end with the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. However, many colonists were angered when Britain returned Louisbourg to France in return for Madras and other territories.[59] In the aftermath of the war, both the British and French sought to expand into the Ohio River valley.[60]

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was the American extension of the general European conflict known as the Seven Years' War. Previous colonial wars in North America had started in Europe and then spread to the colonies, but the French and Indian War is notable for having started in North America and spread to Europe. One of the primary causes of the war was increasing competition between Britain and France, especially in the Great Lakes and Ohio valley.[61]

The French and Indian War took on a new significance for the British North American colonists when William Pitt the Elder decided that major military resources needed to be devoted to North America in order to win the war against France. For the first time, the continent became one of the main theaters of what could be termed a "world war". During the war, it became increasingly apparent to American colonists that they were under the authority of the British Empire, as British military and civilian officials took on an increased presence in their lives.

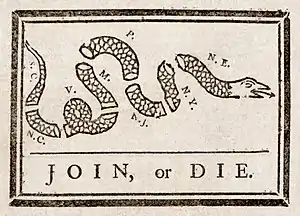

The war also increased a sense of American unity in other ways. It caused men to travel across the continent who might otherwise have never left their own colony, fighting alongside men from decidedly different backgrounds who were nonetheless still American. Throughout the course of the war, British officers trained Americans for battle, most notably George Washington, which benefited the American cause during the Revolution. Also, colonial legislatures and officials had to cooperate intensively in pursuit of the continent-wide military effort.[61] The relations were not always positive between the British military establishment and the colonists, setting the stage for later distrust and dislike of British troops. At the 1754 Albany Congress, Pennsylvania colonist Benjamin Franklin proposed the Albany Plan which would have created a unified government of the Thirteen Colonies for coordination of defense and other matters, but the plan was rejected by the leaders of most colonies.[62]

In the Treaty of Paris (1763), France formally ceded to Britain the eastern part of its vast North American empire, having secretly given to Spain the territory of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River the previous year. Before the war, Britain held the thirteen American colonies, most of present-day Nova Scotia, and most of the Hudson Bay watershed. Following the war, Britain gained all French territory east of the Mississippi River, including Quebec, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio River valley. Britain also gained Spanish Florida, from which it formed the colonies of East and West Florida. In removing a major foreign threat to the thirteen colonies, the war also largely removed the colonists' need of colonial protection.

The British and colonists triumphed jointly over a common foe. The colonists' loyalty to the mother country was stronger than ever before. However, disunity was beginning to form. British Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder had decided to wage the war in the colonies with the use of troops from the colonies and tax funds from Britain itself. This was a successful wartime strategy but, after the war was over, each side believed that it had borne a greater burden than the other. The British elite, the most heavily taxed of any in Europe, pointed out angrily that the colonists paid little to the royal coffers. The colonists replied that their sons had fought and died in a war that served European interests more than their own. This dispute was a link in the chain of events that soon brought about the American Revolution.[61]

Growing dissent

The British were left with large debts following the French and Indian War, so British leaders decided to increase taxation and control of the Thirteen Colonies.[63] They imposed several new taxes, beginning with the Sugar Act of 1764. Later acts included the Currency Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and the Townshend Acts of 1767.[64]

The British also sought to maintain peaceful relations with those Indian tribes that had allied with the French by keeping them separated from the American frontiersmen. To this end, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 restricted settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, as this was designated an Indian Reserve.[65] Some groups of settlers disregarded the proclamation, however, and continued to move west and establish farms.[66] The proclamation was soon modified and was no longer a hindrance to settlement, but the fact angered the colonists that it had been promulgated without their prior consultation.[67]

Parliament had directly levied duties and excise taxes on the colonies, bypassing the colonial legislatures, and Americans began to insist on the principle of "no taxation without representation" with intense protests over the Stamp Act of 1765.[68] They argued that the colonies had no representation in the British Parliament, so it was a violation of their rights as Englishmen for taxes to be imposed upon them. Parliament rejected the colonial protests and asserted its authority by passing new taxes.

Colonial discontentment grew with the passage of the 1773 Tea Act, which reduced taxes on tea sold by the East India Company in an effort to undercut competition, and Prime Minister North's ministry hoped that this would establish a precedent of colonists accepting British taxation policies. Trouble escalated over the tea tax, as Americans in each colony boycotted the tea, and those in Boston dumped the tea in the harbor during the Boston Tea Party in 1773 when the Sons of Liberty dumped thousands of pounds of tea into the water. Tensions escalated in 1774 as Parliament passed the laws known as the Intolerable Acts, which greatly restricted self-government in the colony of Massachusetts. These laws also allowed British military commanders to claim colonial homes for the quartering of soldiers, regardless whether the American civilians were willing or not to have soldiers in their homes. The laws further revoked colonial rights to hold trials in cases involving soldiers or crown officials, forcing such trials to be held in England rather than in America. Parliament also sent Thomas Gage to serve as Governor of Massachusetts and as the commander of British forces in North America.[69]

By 1774, colonists still hoped to remain part of the British Empire, but discontentment was widespread concerning British rule throughout the Thirteen Colonies.[70] Colonists elected delegates to the First Continental Congress which convened in Philadelphia in September 1774. In the aftermath of the Intolerable Acts, the delegates asserted that the colonies owed allegiance only to the king; they would accept royal governors as agents of the king, but they were no longer willing to recognize Parliament's right to pass legislation affecting the colonies. Most delegates opposed an attack on the British position in Boston, and the Continental Congress instead agreed to the imposition of a boycott known as the Continental Association. The boycott proved effective and the value of British imports dropped dramatically.[71] The Thirteen Colonies became increasingly divided between Patriots opposed to British rule and Loyalists who supported it.[72]

American Revolution

In response, the colonies formed bodies of elected representatives known as Provincial Congresses, and Colonists began to boycott imported British merchandise.[73] Later in 1774, 12 colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. During the Second Continental Congress, the remaining colony of Georgia sent delegates, as well.

Massachusetts Governor Thomas Gage feared a confrontation with the colonists; he requested reinforcements from Britain, but the British government was not willing to pay for the expense of stationing tens of thousands of soldiers in the Thirteen Colonies. Gage was instead ordered to seize Patriot arsenals. He dispatched a force to march on the arsenal at Concord, Massachusetts, but the Patriots learned about it and blocked their advance. The Patriots repulsed the British force at the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, then lay siege to Boston.[74]

By spring 1775, all royal officials had been expelled, and the Continental Congress hosted a convention of delegates for the 13 colonies. It raised an army to fight the British and named George Washington its commander, made treaties, declared independence, and recommended that the colonies write constitutions and become states.[75] The Second Continental Congress assembled in May 1775 and began to coordinate armed resistance against Britain. It established a government that recruited soldiers and printed its own money. General Washington took command of the Patriot soldiers in New England and forced the British to withdraw from Boston. In 1776, the Thirteen Colonies declared their independence from Britain. With the help of France and Spain, they defeated the British in the American Revolutionary War, with the final battle usually being referred to as the Siege of Yorktown in 1781. In the Treaty of Paris (1783), Britain officially recognized the independence of the United States of America.

Thirteen British colonies population

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1625 | 1,980 |

| 1641 | 50,000 |

| 1688 | 200,000 |

| 1702 | 270,000 |

| 1715 | 435,000 |

| 1749 | 1,000,000 |

| 1754 | 1,500,000 |

| 1765 | 2,200,000 |

| 1775 | 2,400,000 |

The colonial population rose to a quarter of a million during the 17th century, and to nearly 2.5 million on the eve of the American revolution. The estimates do not include the Indian tribes outside the jurisdiction of the colonies. Perkins (1988) notes the importance of good health for the growth of the colonies: "Fewer deaths among the young meant that a higher proportion of the population reached reproductive age, and that fact alone helps to explain why the colonies grew so rapidly."[77] There were many other reasons for the population growth besides good health, such as the Great Migration.

By 1776, about 85% of the white population's ancestry originated in the British Isles (English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh), 9% of German origin, 4% Dutch and 2% Huguenot French and other minorities. Over 90% were farmers, with several small cities that were also seaports linking the colonial economy to the larger British Empire. These populations continued to grow at a rapid rate during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, primarily because of high birth rates and relatively low death rates. Immigration was a minor factor from 1774 to 1830.[78] The Federal Census Bureau study of 2004 gives the following population estimates for the colonies: 1610 350; 1620 2,302; 1630 4,646; 1640 26,634; 1650 50,368; 1660 75,058; 1670 111,935; 1680 151,507; 1690 210,372; 1700 250,888; 1710 331,711; 1720 466,185; 1730 629,445; 1740 905,563; 1750 170,760; 1760 1,593,625; 1770 2,148,076; 1780 2,780,369. CT970 p. 2-13: Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics, United States Census Bureau 2004, p. 1168.

According to the United States Historical Census Data Base (USHCDB), the ethnic populations in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, and 1775 were:

| Ethnic composition in the British American Colonies of 1700 • 1755 • 1775 [79][80][81] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700 | Percent | 1755 | Percent | 1775 | Percent |

| English and Welsh | 80.0% | English and Welsh | 52.0% | English | 48.7% |

| African | 11.0% | African | 20.0% | African | 20.0% |

| Dutch | 4.0% | German | 7.0% | Scots-Irish | 7.8% |

| Scottish | 3.0% | Scots-Irish | 7.0% | German | 6.9% |

| Other European | 2.0% | Irish | 5.0% | Scottish | 6.6% |

| Scottish | 4.0% | Dutch | 2.7% | ||

| Dutch | 3.0% | French | 1.4% | ||

| Other European | 2.0% | Swedish | 0.6% | ||

| Other | 5.3% | ||||

| Colonies | 100% | Colonies | 100% | Thirteen Colonies | 100% |

Slaves

Slavery was legal and practiced in all of the Thirteen Colonies.[4] In most places, it involved house servants or farm workers. It was of economic importance in the export-oriented tobacco plantations of Virginia and Maryland and on the rice and indigo plantations of South Carolina.[82] About 287,000 slaves were imported into the Thirteen Colonies over a period of 160 years, or 2% of the estimated 12 million taken from Africa to the Americas via the Atlantic slave trade. The great majority went to sugar colonies in the Caribbean and to Brazil, where life expectancy was short and the numbers had to be continually replenished. By the mid-18th century, life expectancy was much higher in the American colonies.[83]

| 1620–1700 | 1701–1760 | 1761–1770 | 1771–1780 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21,000 | 189,000 | 63,000 | 15,000 | 288,000 |

The numbers grew rapidly through a very high birth rate and low mortality rate, reaching nearly four million by the 1860 census. From 1770 until 1860, the rate of natural growth of North American slaves was much greater than for the population of any nation in Europe, and was nearly twice as rapid as that in England.

Religion

Protestantism was the predominant religious affiliation in the Thirteen Colonies, although there were also Catholics, Jews, and deists, and a large fraction had no religious connection. The Church of England was officially established in most of the South. The Puritan movement became the Congregational church, and it was the established religious affiliation in Massachusetts and Connecticut into the 18th century.[85] In practice, this meant that tax revenues were allocated to church expenses. The Anglican parishes in the South were under the control of local vestries and had public functions such as repair of the roads and relief of the poor.[86]

The colonies were religiously diverse, with different Protestant denominations brought by British, German, Dutch, and other immigrants. The Reformed tradition was the foundation for Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Continental Reformed denominations. French Huguenots set up their own Reformed congregations. The Dutch Reformed Church was strong among Dutch Americans in New York and New Jersey, while Lutheranism was prevalent among German immigrants. Germans also brought diverse forms of Anabaptism, especially the Mennonite variety. Reformed Baptist preacher Roger Williams founded Providence Plantations which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Jews were clustered in a few port cities. The Baltimore family founded Maryland and brought in fellow Catholics from England.[87] Catholics were estimated at 1.6% of the population or 40,000 in 1775. Of the 200–250,000 Irish who came to the Colonies between 1701 and 1775 less than 20,000 were Catholic, many of whom hid their faith or lapsed because of prejudice and discrimination. Between 1770 and 1775 3,900 Irish Catholics arrived out of almost 45,000 white immigrants (7,000 English, 15,000 Scots, 13,200 Scots-Irish, 5,200 Germans).[88] Most Catholics were English Recusants, Germans, Irish, or blacks; half lived in Maryland, with large populations also in New York and Pennsylvania. Presbyterians were chiefly immigrants from Scotland and Ulster who favored the back country and frontier districts.[89]

Quakers were well established in Pennsylvania, where they controlled the governorship and the legislature for many years.[90] Quakers were also numerous in Rhode Island. Baptists and Methodists were growing rapidly during the First Great Awakening of the 1740s.[91] Many denominations sponsored missions to the local Indians.[92]

Education

Higher education was available for young men in the north, and most students were aspiring Protestant ministers. The oldest colleges were New College (Harvard), College of New Jersey (Princeton), Collegiate School (Yale), King's College (Columbia), and the College of Rhode Island (Brown). Other colleges were College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania), Queen's College (Rutgers) and Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. South of Philadelphia, there was only the College of William and Mary which trained the secular elite in Virginia, especially aspiring lawyers.

The southern colonies held the belief that the family had the responsibility of educating their children, mirroring the common belief in Europe. Wealthy families either used tutors and governesses from Britain or sent children to school in England. By the 1700s, university students based in the colonies began to act as tutors.[93]

Most New England towns sponsored public schools for boys, but public schooling was rare elsewhere. Girls were educated at home or by small local private schools, and they had no access to college. Aspiring physicians and lawyers typically learned as apprentices to an established practitioner, although some young men went to medical schools in Scotland.[94]

Government

The three forms of colonial government in 1776 were provincial (royal colony), proprietary, and charter. These governments were all subordinate to the British monarch with no representation in the Parliament of Great Britain. The administration of all British colonies was overseen by the Board of Trade in London beginning late in the 17th century.

The provincial colony was governed by commissions created at pleasure of the king. A governor and his council were appointed by the crown. The governor was invested with general executive powers and authorized to call a locally elected assembly. The governor's council would sit as an upper house when the assembly was in session, in addition to its role in advising the governor. Assemblies were made up of representatives elected by the freeholders and planters (landowners) of the province. The governor had the power of absolute veto and could prorogue (i.e., delay) and dissolve the assembly. The assembly's role was to make all local laws and ordinances, ensuring that they were not inconsistent with the laws of Britain. In practice, this did not always occur, since many of the provincial assemblies sought to expand their powers and limit those of the governor and crown. Laws could be examined by the British Privy Council or Board of Trade, which also held veto power of legislation. New Hampshire, New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were crown colonies. Massachusetts became a crown colony at the end of the 17th century.

Proprietary colonies were governed much as royal colonies, except that lord proprietors appointed the governor rather than the king. They were set up after the English Restoration of 1660 and typically enjoyed greater civil and religious liberty. Pennsylvania (which included Delaware), New Jersey, and Maryland were proprietary colonies.[95]

Charter governments were political corporations created by letters patent, giving the grantees control of the land and the powers of legislative government. The charters provided a fundamental constitution and divided powers among legislative, executive, and judicial functions, with those powers being vested in officials. Massachusetts, Providence Plantation, Rhode Island, Warwick, and Connecticut were charter colonies. The Massachusetts charter was revoked in 1684 and was replaced by a provincial charter that was issued in 1691.[96] Providence Plantations merged with the settlements at Rhode Island and Warwick to form the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, which also became a charter colony in 1636.

British role

After 1680, the imperial government in London took an increasing interest in the affairs of the colonies, which were growing rapidly in population and wealth. In 1680, only Virginia was a royal colony; by 1720, half were under the control of royal governors. These governors were appointees closely tied to the government in London.

Historians before the 1880s emphasized American nationalism. However, scholarship after that time was heavily influenced by the "Imperial school" led by Herbert L. Osgood, George Louis Beer, Charles McLean Andrews, and Lawrence H. Gipson. This viewpoint dominated colonial historiography into the 1940s, and they emphasized and often praised the attention that London gave to all the colonies. In this view, there was never a threat (before the 1770s) that any colony would revolt or seek independence.[97]

Self-government

British settlers did not come to the American colonies with the intention of creating a democratic system; yet they quickly created a broad electorate without a land-owning aristocracy, along with a pattern of free elections which put a strong emphasis on voter participation. The colonies offered a much freer degree of suffrage than Britain or indeed any other country. Any property owner could vote for members of the lower house of the legislature, and they could even vote for the governor in Connecticut and Rhode Island.[98] Voters were required to hold an "interest" in society; as the South Carolina legislature said in 1716, "it is necessary and reasonable, that none but such persons will have an interest in the Province should be capable to elect members of the Commons House of Assembly".[99] The main legal criterion for having an "interest" was ownership of real estate property, which was uncommon in Britain, where 19 out of 20 men were controlled politically by their landlords. (Women, children, indentured servants, and slaves were subsumed under the interest of the family head.) London insisted on this requirement for the colonies, telling governors to exclude from the ballot men who were not freeholders—that is, those who did not own land. Nevertheless, land was so widely owned that 50% to 80% of the men were eligible to vote.[100]

The colonial political culture emphasized deference, so that local notables were the men who ran and were chosen. But sometimes they competed with each other and had to appeal to the common man for votes. There were no political parties, and would-be legislators formed ad hoc coalitions of their families, friends, and neighbors. Outside of Puritan New England, election day brought in all the men from the countryside to the county seat to make merry, politick, shake hands with the grandees, meet old friends, and hear the speeches—all the while toasting, eating, treating, tippling, and gambling. They voted by shouting their choice to the clerk, as supporters cheered or booed. Candidate George Washington spent £39 for treats for his supporters. The candidates knew that they had to "swill the planters with bumbo" (rum). Elections were carnivals where all men were equal for one day and traditional restraints were relaxed.[101]

The actual rate of voting ranged from 20% to 40% of all adult white males. The rates were higher in Pennsylvania and New York, where long-standing factions based on ethnic and religious groups mobilized supporters at a higher rate. New York and Rhode Island developed long-lasting two-faction systems that held together for years at the colony level, but they did not reach into local affairs. The factions were based on the personalities of a few leaders and an array of family connections, and they had little basis in policy or ideology. Elsewhere the political scene was in a constant whirl, based on personality rather than long-lived factions or serious disputes on issues.[98]

The colonies were independent of one other long before 1774; indeed, all the colonies began as separate and unique settlements or plantations. Further, efforts had failed to form a colonial union through the Albany Congress of 1754 led by Benjamin Franklin. The thirteen all had well-established systems of self-government and elections based on the Rights of Englishmen which they were determined to protect from imperial interference.[102]

Economic policy

The British Empire at the time operated under the mercantile system, where all trade was concentrated inside the Empire, and trade with other empires was forbidden. The goal was to enrich Britain—its merchants and its government. Whether the policy was good for the colonists was not an issue in London, but Americans became increasingly restive with mercantilist policies.[103]

Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants—and kept others out—by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximize exports from and minimize imports to the realm. The government had to fight smuggling—which became a favorite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch.[104] The tactic used by mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a superb Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. Thus the British Navy captured New Amsterdam (New York) in 1664. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.[105]

Britain implemented mercantilism by trying to block American trade with the French, Spanish, or Dutch empires using the Navigation Acts, which Americans avoided as often as they could. The royal officials responded to smuggling with open-ended search warrants (Writs of Assistance). In 1761, Boston lawyer James Otis argued that the writs violated the constitutional rights of the colonists. He lost the case, but John Adams later wrote, "Then and there the child Independence was born."[106]

However, the colonists took pains to argue that they did not oppose British regulation of their external trade; they only opposed legislation which affected them internally.

Other British colonies

- Newfoundland

- Nova Scotia

- Thirteen Colonies

- Bermuda

- Bahamas

- British Honduras

- Jamaica

- British Leeward Islands and Barbados

Besides the grouping that became known as the "thirteen colonies",[107] Britain in the late-18th century had another dozen colonial possessions in the New World. The British West Indies, Newfoundland, the Province of Quebec, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Bermuda, and East and West Florida remained loyal to the British crown throughout the war (although Spain reacquired Florida before the war was over, and in 1821 sold it to the United States). Several of the other colonies evinced a certain degree of sympathy with the Patriot cause, but their geographical isolation and the dominance of British naval power precluded any effective participation.[108] The British crown had only recently acquired several of those lands, and many of the issues facing the Thirteen Colonies did not apply to them, especially in the case of Quebec and Florida.[109]

- Sparsely-settled Rupert's Land, which King Charles II of England had chartered as "one of our Plantations or Colonies in America" in 1670,[110] operated remotely from the rebellious colonies and had relatively little in common with them.

- Newfoundland, exempt from the Navigation Acts, shared none of the grievances of the continental colonies. Tightly bound to Britain and controlled by the Royal Navy, it had no assembly that could voice grievances.

- Nova Scotia had a large Yankee element which had recently arrived from New England, and which shared the sentiments of the Americans in the 13 colonies about demanding the rights of the British men. The royal government in Halifax reluctantly allowed the Yankees of Nova Scotia a kind of "neutrality". In any case, the island-like geography and the presence of the major British naval-base at Halifax made the thought of armed resistance impossible.[111]

- Quebec was inhabited by French Catholic settlers who had come under British control by 1760. The Quebec Act of 1774 gave the French settlers formal cultural autonomy within the British Empire, and many of their Catholic priests feared the intense Protestantism in New England. American grievances over taxation had little relevance, and there was no assembly nor elections of any kind that could have mobilized any grievances. Even so, the Americans offered the Quebecois membership in their new country and sent a military expedition that failed to capture Canada in 1775. Most Canadians remained neutral, but some joined the American cause.[112]

- In the West Indies the elected assemblies of Jamaica, Grenada, and Barbados formally declared their sympathies for the American cause and called for mediation, but the others were quite loyal. Britain carefully avoided antagonizing the rich owners of sugar-plantations (many of whom lived in London); in turn the planters' greater dependence on slavery made them recognize the need for British military protection from possible slave revolts. The possibilities for overt action were sharply limited by the overwhelming power of Royal Navy in the islands. During the war there was some opportunistic trading with American ships.[113]

- In Bermuda and in the Bahamas, local leaders were angry at the food shortages caused by British blockade of American ports. There was increasing sympathy for the American cause, which extended to smuggling, and both colonies were considered "passive allies" of the United States throughout the war. When an American naval squadron arrived in the Bahamas to seize gunpowder, the colony offered no resistance at all.[114]

- Spain had transferred the territories of East Florida and West Florida to Britain by the Treaty of Paris in 1763 after the French and Indian War. The few British colonists there needed protection from attacks by Indians and by Spanish privateers. After 1775 East Florida became a major base for the British war-effort in the South, especially in the invasions of Georgia and South Carolina.[115] However, Spain seized Pensacola in West Florida in 1781, then recovered both territories in the Treaty of Paris that ended the war in 1783. Spain ultimately agreed to transfer the Florida provinces to the United States in 1819.[116]

Historiography

The first British Empire centered on the Thirteen Colonies, which attracted large numbers of settlers from Britain. The "Imperial School" in the 1900–1930s took a favorable view of the benefits of empire, emphasizing its successful economic integration.[117] The Imperial School included such historians as Herbert L. Osgood, George Louis Beer, Charles M. Andrews, and Lawrence Gipson.[118]

The shock of Britain's defeat in 1783 caused a radical revision of British policies on colonialism, thereby producing what historians call the end of the First British Empire, even though Britain still controlled Canada and some islands in the West Indies.[119] Ashley Jackson writes:

The first British Empire was largely destroyed by the loss of the American colonies, followed by a "swing to the east" and the foundation of a second British Empire based on commercial and territorial expansion in South Asia.[120]

Much of the historiography concerns the reasons why the Americans rebelled in the 1770s and successfully broke away. Since the 1960s, the mainstream of historiography has emphasized the growth of American consciousness and nationalism and the colonial republican value-system, in opposition to the aristocratic viewpoint of British leaders.[121]

Historians in recent decades have mostly used one of three approaches to analyze the American Revolution:[122]

- The Atlantic history view places North American events in a broader context, including the French Revolution and Haitian Revolution. It tends to integrate the historiographies of the American Revolution and the British Empire.[123][124]

- The new social history approach looks at community social structure to find issues that became magnified into colonial cleavages.

- The ideological approach centers on republicanism in the Thirteen Colonies.[125] The ideas of republicanism dictated that the United States would have no royalty or aristocracy or national church. They did permit continuation of the British common law, which American lawyers and jurists understood, approved of, and used in their everyday practice. Historians have examined how the rising American legal profession adapted the British common law to incorporate republicanism by selective revision of legal customs and by introducing more choice for courts.[126][127]

See also

- American Revolutionary War#Prelude to revolution

- British colonization of the Americas

- Colonial American military history

- Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies

- Colonial history of the United States

- Colonial South and the Chesapeake

- Credit in the Thirteen Colonies

- Cuisine of the Thirteen Colonies

- History of the United States (1776–1789)

- Shipbuilding in the American colonies

- United Colonies, the name used by the Second Continental Congress in 1775-1776

References

- U.S. Bureau of the Census, A century of population growth from the first census of the United States to the twelfth, 1790–1900 (1909) p. 9.

- Galloway, Joseph (1780). Cool thoughts on the consequences of American independence, &c. printed for J. Wilkie. London. p. 57. OCLC 24301390. OL 19213819M. Retrieved October 12, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- South Carolina. Convention (1862). Journal of the Convention of the people of South Carolina. published by order of the Convention. Columbia, S. C.: R. W. Gibbes. p. 461. OCLC 1047483138. Retrieved October 12, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-85109-544-5.

- Richard Middleton and Anne Lombard, Colonial America: A History to 1763 (4th ed. 2011)

- Editors, History com. "The 13 Colonies". HISTORY. Retrieved May 11, 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Richter, pp. 152–53

- The number 13 is mentioned as early as 1720 by Abel Boyer, The Political State of Great Britain vol. 19, p. 376: "so in this Country we have Thirteen Colonies at least severally govern'd by their respective Commanders in Chief, according to their peculiar Laws and Constitutions." This includes Carolina as a single colony and does not include Georgia, but instead counts Nova Scotia and Newfoundland as British colonies. Also see John Roebuck, An Enquiry, Whether the Guilt of the Present Civil War in America, Ought to be Imputed to Great Britain Or America, p. 21: "though the colonies be thus absolutely subject to the parliament of England, the individuals of which the colony consist, may enjoy security, and freedom; there is not a single inhabitant, of the thirteen colonies, now in arms, but who may be conscious of the truth of this assertion". The critical review, or annals of literature vol. 48 (1779), p. 136: "during the last war, no part of his majesty's dominions contained a greater proportion of faithful subjects than the Thirteen Colonies."

- Foulds, Nancy Brown. "Colonial Office". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- Alan Taylor, American Colonies,, 2001.

- Ronald L. Heinemann, Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607–2007, 2008.

- Sparks, Jared (1846). The Library of American Biography: George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown. pp. 16–.

Leonard Calvert.

- Robert M. Weir, Colonial South Carolina: A History (1983).

- Richter, pp. 138–40

- Richter, pp. 159– 60

- Richter pp. 212–13

- Richter pp. 214–15

- Richter pp. 215–17

- Richter, p. 150

- Richter p. 213

- Richter, p. 262

- Richter pp. 247–48

- Richter, pp. 248–49

- Richter, p. 249

- Richter p. 261

- Michael G. Kammen, Colonial New York: A History (1974).

- John E. Pomfret, Colonial New Jersey: A History (1973).

- Joseph E. Illick, Colonial Pennsylvania: a history (1976).

- Weigley, Russell Frank (1982). Philadelphia: A 300 Year History. ISBN 0393016102.

- Nathaniel Philbrick, Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War Paperback (2007).

- Francis J. Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards (1995).

- Taylor, Barbara (December 1998). "Salmon and Steelhead Runs and Related Events of the Sandy River Basin – A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Portland General Electric. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- Benjamin Woods Labaree, Colonial Massachusetts: a history (1979)

- https://www.bostonfed.org/-/media/Documents/education/pubs/historyo.pdf.

- Michael G. Hall; Lawrence H. Leder; Michael Kammen, eds. (December 1, 2012). The Glorious Revolution in America: Documents on the Colonial Crisis of 1689. UNC Press Books. pp. 3–4, 39. ISBN 978-0-8078-3866-2.

- Miller, Guy Howard (1968). "Rebellion in Zion: The Overthrow of the Dominion of New England". The Historian. 30 (3): 439–459. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1968.tb00328.x. JSTOR 24441216.

- Richter, pp. 319–22

- Richter, pp. 323–24

- Colonial charters, grants, and related documents

- Richter, pp. 358–59

- Taylor (2016), p. 20

- Taylor (2016), p. 23

- Taylor (2016), p. 25

- Richter, pp. 373–74

- Richter, pp. 376–77

- Richter, pp. 329–30

- Richter, pp. 332–36

- Richter, pp. 330–31

- Richter, pp. 346–47

- Richter, pp. 351–52

- Richter, pp. 353–54

- Taylor (2016), pp. 18–19

- Richter, p. 360

- Richter, p. 361

- Richter, p. 362

- Middlekauff, pp. 46–49

- Richter, p. 345

- Richter, pp. 379–80

- Richter, pp. 380–81

- Richter, pp. 383–85

- Fred Anderson, The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War (2006)

- Richter, pp. 390–91

- Taylor (2016), pp. 51–53

- Taylor (2016), pp. 94–96, 107

- Colin G. Calloway, The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America (2006), pp. 92–98

- W. J. Rorabaugh, Donald T. Critchlow, Paula C. Baker (2004). "America's promise: a concise history of the United States". Rowman & Littlefield. p. 92. ISBN 0-7425-1189-8

- Holton, Woody (1994). "The Ohio Indians and the coming of the American Revolution in Virginia". Journal of Southern History. 60 (3): 453–78. doi:10.2307/2210989. JSTOR 2210989.

- J. R. Pole, Political Representation in England and the Origins of the American Republic (London; Melbourne: Macmillan, 1966), 31 Questia Online Library

- Taylor (2016), pp. 112–14

- Taylor (2016), pp. 137–21

- Taylor (2016), pp. 123–27

- Taylor (2016), pp. 137–38

- T.H. Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (2010) pp. 81–82

- Taylor (2016), pp. 132–33

- Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (Oxford History of the United States) (2007)

- Note: the population figures are estimates by historians; they do not include the Indian tribes outside the jurisdiction of the colonies. They do include Indians living under colonial control, as well as slaves and indentured servants. U.S. Bureau of the Census, A century of population growth from the first census of the United States to the twelfth, 1790–1900 (1909) p. 9

- Edwin J. Perkins (1988). The Economy of Colonial America. Columbia UP. p. 7. ISBN 9780231063395.

- Smith, Daniel Scott (1972). "The Demographic History of Colonial New England". The Journal of Economic History. 32 (1): 165–83. doi:10.1017/S0022050700075458. JSTOR 2117183. PMID 11632252.

- Boyer, Paul S.; Clark, Clifford E.; Halttunen, Karen; Kett, Joseph F.; Salisbury, Neal; Sitkoff, Harvard; Woloch, Nancy (2013). The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 99. ISBN 978-1133944522.

- "Scots to Colonial North Carolina Before 1775". Dalhousielodge.org. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "U.S. Federal Census : United States Federal Census : US Federal Census". 1930census.com. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Betty Wood, Slavery in Colonial America, 1619–1776 (2013) excerpt and text search

- Paul Finkelman (2006). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895. Oxford UP. pp. 2:156. ISBN 9780195167771.

- Source: Miller and Smith, eds. Dictionary of American Slavery (1988) p . 678

- Stephen Foster, The Long Argument: English Puritanism and the Shaping of New England Culture, 1570–1700; (1996).

- Patricia U. Bonomi, Under the cope of heaven: Religion, society, and politics in Colonial America (2003).

- Rita, M. (1940). "Catholicism in Colonial Maryland". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 51 (1): 65–83. JSTOR 44209361.

- Jon Butler, Becoming America, The Revolution before 1776, 2000, p. 35, ISBN 0-674-00091-9

- Bryan F. Le Beau, Jonathan Dickinson and the Formative Years of American Presbyterianism (2015).

- Gary B. Nash, Quakers and Politics: Pennsylvania, 1681–1726 (1993).

- Thomas S. Kidd, and Barry Hankins, Baptists in America: A History (2015) ch 1.

- Laura M. Stevens, The poor Indians: British missionaries, Native Americans, and colonial sensibility (2010).

- Urban, Wayne J. and Jennings L. Wagoner, Jr. American Education: A History. Routledge, August 11, 2008. ISBN 1135267987, 9781135267988. p. 24-25.

- Wayne J. Urban and Jennings L. Wagoner Jr., American Education: A History (5th ed. 2013) pp 11–54.

- John Andrew Doyle, English Colonies in America: Volume IV The Middle Colonies (1907) online

- Louise Phelps Kellogg, The American colonial charter (1904) online

- Savelle, Max (1949). "The Imperial School of American Colonial Historians". Indiana Magazine of History. 45 (2): 123–134. JSTOR 27787750.

- Robert J. Dinkin, Voting in Provincial America: A Study of Elections in the Thirteen Colonies, 1689–1776 (1977)

- Thomas Cooper and David James McCord, eds. The Statutes at Large of South Carolina: Acts, 1685–1716 (1837) p. 688

- Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote (2000) pp. 5–8

- Daniel Vickers, A Companion to Colonial America (2006) p. 300

- Greene and Pole, eds. (2004), p. 665

- Max Savelle, Seeds of Liberty: The Genesis of the American Mind (2005) pp. 204–11

- George Otto Trevelyan, The American revolution: Volume 1 (1899) p. 128 online

- William R. Nester, The Great Frontier War: Britain, France, and the Imperial Struggle for North America, 1607–1755 (Praeger, 2000) p, 54.

- Stephens, Unreasonable Searches and Seizures (2006) p. 306

- Recorded usage of the term, 1700-1800.

- Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2004) ch. 63

- Lawrence Gipson, The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 volumes, 1936–1970), highly detailed discussion of every British colony in the New World in the 1750s and 1760s

- Royal Charter of the Hudson's Bay Company.

- Meinig pp. 313–14; Greene and Pole (2004) ch. 61.

- Meinig pp 314–15; Greene and Pole (2004) ch 61.

- Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean (2000) ch 6

- Meinig pp. 315–16; Greene and Pole (2004) ch. 63

- Meinig p. 316

- P. J. Marshall, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume II: The Eighteenth Century (2001).

- Robert L. Middlekauff, "The American Continental Colonies in the Empire", in Robin Winks, ed., The Historiography of the British Empire-Commonwealth: Trends, Interpretations and Resources (1966) pp. 23–45.

- William G. Shade, "Lawrence Henry Gipson's Empire: The Critics". Pennsylvania History (1969): 49–69 online.

- Brendan Simms, Three victories and a defeat: the rise and fall of the first British Empire 2008

- Ashley Jackson (2013). The British Empire: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford UP. p. 72. ISBN 9780199605415.

- Tyrrell, Ian (1999). "Making Nations/Making States: American Historians in the Context of Empire". The Journal of American History. 86 (3): 1015–1044. doi:10.2307/2568604. JSTOR 2568604.

- Winks, Historiography 5:95

- Cogliano, Francis D. (2010). "Revisiting the American Revolution". History Compass. 8 (8): 951–63. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2010.00705.x.

- Eliga H. Gould, Peter S. Onuf, eds. Empire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic World (2005)

- Compare: David Kennedy; Lizabeth Cohen (2015). American Pageant. Cengage Learning. p. 156. ISBN 9781305537422.

[...] the neoprogressives [...] have argued that the varying material circumstances of American participants led them to hold distinctive versions of republicanism, giving the Revolution a less unified and more complex ideological underpinning than the idealistic historians had previously suggested.

- Ellen Holmes Pearson. "Revising Custom, Embracing Choice: Early American Legal Scholars and the Republicanization of the Common Law", in Gould and Onuf, eds. Empire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic World (2005) pp. 93–113

- Anton-Hermann Chroust, Rise of the Legal Profession in America (1965) vol. 2.

Works cited

- Richter, Daniel (2011). Before the Revolution : America's ancient pasts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press.

- Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804 (2016) recent survey by leading scholar

Further reading

- Adams, James Truslow (1922). The Founding of New England. Atlantic Monthly Press; full text online.

- Adams, James Truslow. Revolutionary New England, 1691–1776 (1923)

- Andrews, Charles M. The Colonial Period of American History (4 vol. 1934–38), the standard political overview to 1700

- Carr, J. Revell (2008). Seeds of Discontent: The Deep Roots of the American Revolution, 1650–1750. Walker Books.

- Chitwood, Oliver. A history of colonial America (1961), older textbook

- Cooke, Jacob Ernest et al., ed. Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies. (3 vol. 1993); 2397 pp.; comprehensive coverage; compares British, French, Spanish & Dutch colonies

- Elliott, John (2006). Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492–1830. Yale University Press.

- Foster, Stephen, ed. British North America in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (2014) doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199206124.001.0001

- Gipson, Lawrence. The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 volumes, 1936–1970), Pulitzer Prize; highly detailed discussion of every British colony in the New World

- Greene, Evarts Boutelle et al., American Population before the Federal Census of 1790, 1993, ISBN 0-8063-1377-3

- Greene, Evarts Boutell (1905). Provincial America, 1690–1740. Harper & brothers; full text online.

- Hawke, David F.; The Colonial Experience; 1966, ISBN 0-02-351830-8. older textbook

- Hawke, David F. Everyday Life in Early America (1989) excerpt and text search

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution, 1763–1789. Oxford University Press.

- Middleton, Richard, and Anne Lombard. Colonial America: A History to 1763 (4th ed. 2011), the newest textbook excerpt and text search

- Taylor, Alan. American colonies (2002), 526 pages; recent survey by leading scholar

- Vickers, Daniel, ed. A Companion to Colonial America. (Blackwell, 2003) 576 pp.; topical essays by experts excerpt

Government

- Andrews, Charles M.Colonial Self-Government, 1652–1689 (1904) full text online

- Dinkin, Robert J. Voting in Provincial America: A Study of Elections in the Thirteen Colonies, 1689–1776 (1977)

- Miller, John C. Origins of the American Revolution (1943)

- Osgood, Herbert L. The American colonies in the seventeenth century, (3 vol 1904–07) vol. 1 online; vol 2 online; vol 3 online

- Osgood, Herbert L. The American colonies in the eighteenth century (4 vols, 1924–25)

Primary sources

- Commager, Henry Steele and Richard B. Morris, eds. The Spirit of 'Seventy-Six': The Story of the American Revolution as told by Participants. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1958). online

- Kavenagh, W. Keith, ed. Foundations of Colonial America: a Documentary History (6 vol. 1974)

- Sarson, Steven, and Jack P. Greene, eds. The American Colonies and the British Empire, 1607–1783 (8 vol, 2010); primary sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thirteen Colonies. |