History of US science fiction and fantasy magazines to 1950

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.

In 1933 Astounding was acquired by Street & Smith, and it soon became the leading magazine in the new genre, publishing early classics such as Murray Leinster's "Sidewise in Time" in 1934. A couple of competitors to Weird Tales for fantasy and weird fiction appeared, but none lasted, and the 1930s is regarded as Weird Tales' heyday. Between 1939 and 1941 there was a boom in science-fiction and fantasy magazines: several publishers entered the field, including Standard Magazines, with Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories (a retitling of Wonder Stories); Popular Publications, with Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories; and Fiction House, with Planet Stories, which focused on melodramatic tales of interplanetary adventure. Ziff-Davis launched Fantastic Adventures, a fantasy companion to Amazing. Astounding extended its pre-eminence in the field during the boom: the editor, John W. Campbell, developed a stable of young writers that included Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and A.E. van Vogt. The period starting in 1938, when Campbell took control of Astounding, is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Well-known stories from this era include Slan, by van Vogt, and "Nightfall", by Asimov. Campbell also launched Unknown, a fantasy companion to Astounding, in 1939; this was the first serious competitor for Weird Tales. Although wartime paper shortages forced Unknown's cancellation in 1943, it is now regarded as one of the most influential pulp magazines.

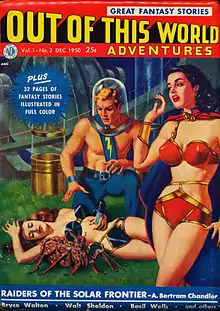

Only eight science-fiction and fantasy magazines survived World War II. All were still in pulp magazine format except for Astounding, which had switched to a digest format in 1943. Astounding continued to publish popular stories, including "Vintage Season" by C. L. Moore, and "With Folded Hands ..." by Jack Williamson. The quality of the fiction in the other magazines improved over the decade: Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder in particular published some excellent material and challenged Astounding for the leadership of the field. A few more pulps were launched in the late 1940s, but almost all were intended as vehicles to reprint old classics. One exception, Out of This World Adventures, was an experiment by Avon, combining fiction with some pages of comics. It was a failure and lasted only two issues. Magazines in digest format began to appear towards the end of the decade, including Other Worlds, edited by Raymond Palmer. In 1949, the first issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction appeared, followed in October 1950 by the first issue of Galaxy Science Fiction; both were digests, and between them soon dominated the field. Very few science-fiction or fantasy pulps were launched after this date; the 1950s was the beginning of the era of digest magazines, though the leading pulps continued until the mid-1950s, and authors began selling to mainstream magazines and large book publishers.

Early magazines

By the end of the 19th century, stories with recognizably science fictional content were appearing regularly in American magazines.[1][note 1] These magazines typically did not print fiction to the exclusion of other content; they would include non-fiction articles and poetry as well. In October 1896, the Frank A. Munsey company's Argosy magazine was the first to switch to printing only fiction, and in December of that year it began using cheap wood-pulp paper. This is now regarded by magazine historians as having been the start of the pulp magazine era.[3][note 2] For twenty years the pulps were successful without restricting their fiction content to any specific genre, but in 1915 the influential magazine publisher Street & Smith began to issue titles that focused on a particular niche, such as Detective Story Magazine and Western Story Magazine, thus pioneering the specialized and single-genre pulps.[5][3]

As the pulps proliferated, they continued to carry science fiction (SF), both in the general fiction magazines such as Argosy and All-Story, and in the more specialized titles such as sports, detective fiction, and (especially) the hero pulps.[6][7] Science fiction also appeared outside the world of pulps: Hugo Gernsback, who had begun his career as an editor and publisher in 1908 with a radio hobbyist magazine called Modern Electrics, soon began including articles speculating about future uses of science, such as "Wireless on Saturn", which appeared in the December 1908 issue. The article was written with enough humour to make it clear to his readers that it was simply an imaginative exercise, but in 1911 Modern Electrics began serializing Ralph 124C 41+, a novel set in the year 2660. In 1913 Gernsback launched another magazine, The Electrical Experimenter (retitled Science and Invention in 1920), which frequently ran science fictional tales, written both by Gernsback and others.[8]

In 1919, Street & Smith launched The Thrill Book, a magazine for stories that were unusual or unclassifiable in some way, which in most cases meant that they included either fantasy or science-fiction elements.[5][9][note 3][note 4] The Thrill Book ceased publication in October 1919, having lasted sixteen issues; it carried some science fiction, particularly towards the end of its short run, but is not generally regarded as a science-fiction or fantasy pulp.[10] Two years later, Gernsback launched yet another magazine, titled Practical Electrics, and in 1924 he sent a letter to its subscribers suggesting a magazine that would publish only scientific fiction. The response was weak, and Gernsback shelved the project.[12]

Weird Tales and Amazing Stories

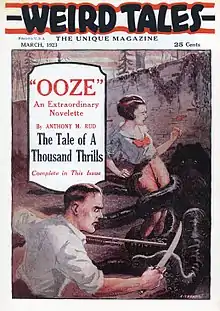

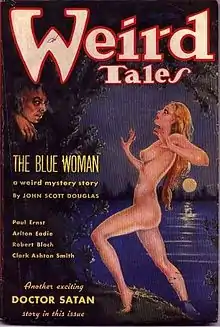

The first magazine to be primarily associated with fantasy and science fiction was Weird Tales, which appeared in March 1923.[13] It was initially edited by Edwin Baird and issued by Rural Publishing, a company owned by Jacob Clark Henneberger and John M. Lansinger. Rural had previously launched the magazine Detective Tales. Weird Tales was intended to provide a market for fantasy and weird fiction, and Henneberger was keen to obtain material unusual enough that it could not be sold to the existing pulp magazines. The planned monthly schedule soon began to slip, skipping July and December. As early as February 1924, Farnsworth Wright took over from Baird as interim editor.[14] After the May–June-July 1924 Anniversary Issue was published, Henneberger and Lansinger split the company, each taking one of the magazines. Henneberger kept nominal control of Weird Tales, while the Cornelius Printing Company, of Indianapolis, to whom Rural owed most of its debt, took over primary ownership.[15] The magazine went on hiatus for five months while Cornelius built a new printing plant.[16] Weird Tales resumed publication with the November 1924 issue, with Farnsworth Wright as permanent editor. The magazine quickly began to improve, both in appearance and quality, as Wright nurtured talented fantasy writers such as Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft.[17]

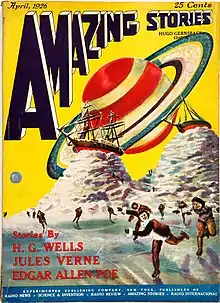

Wright frequently published science fiction, including Edmond Hamilton's first story, which appeared in August 1926, and work by J. Schlossel and Otis Adelbert Kline,[18][19] as well as weird and occult fiction.[20] The first magazine devoted entirely to science fiction joined Weird Tales on the newsstands on 10 March 1926, titled Amazing Stories and dated April. Gernsback had delayed the launch a couple of years after his subscriber survey had shown only limited interest in a science fiction magazine, but finally decided to take the plunge. He ceased publication of Practical Electrics (recently retitled The Experimenter) but retained the editor, T. O'Conor Sloane, to edit the new magazine, though Gernsback had final say over the fiction content. The first issue of Amazing consisted entirely of reprinted material, including Jules Verne's novel Off on a Comet, and stories by H.G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe, but new fiction quickly appeared, with Clare Winger Harris and A. Hyatt Verrill each finding success in one of Gernsback's early reader competitions. Both went on to become established writers. Gernsback also introduced a letter column, and encouraged his readers to join in lively discussions there. In the view of Mike Ashley, a historian of science fiction, this was "the real secret of the success of Amazing Stories and is the cause of the popularity of science fiction": the letter column gave science-fiction fans, many of whom were lonely, a forum in which to make friends and talk about their interests. The resulting community of like-minded readers gave birth to science-fiction fandom, and also to a generation of writers who had grown up reading the genre.[21]

Amazing was very successful, reaching a circulation of 100,000 in less than a year.[21] It was some time before significant competition appeared, but two minor fantasy magazines were launched the year after Amazing's first issue.[22] One, Tales of Magic and Mystery appeared in 1927 and lasted only five issues; it specialized in stories about magic, including a series on Houdini. It was a financial failure, and is now remembered mainly for having published "Cool Air", a story by Lovecraft. The other was Ghost Stories, which was launched in mid-1926 by Bernarr Macfadden, who also published confessional magazines such as True Story. Much of the material in Ghost Stories was written in a similar confessional style, featuring tales of encounters with ghosts presented as true events.[22][23][24]

In June 1927 Gernsback published Amazing Stories Annual, twice the size (and twice the price) of the regular Amazing Stories. It carried a new Mars novel, The Mastermind of Mars, by Edgar Rice Burroughs, which Burroughs had been unable to sell elsewhere, perhaps because it contained satirical elements aimed at religious fundamentalism. Burroughs' name was a powerful aid to sales, and since Gernsback had secured two stories by Abraham Merritt, who was also very popular, the magazine sold out all 150,000 copies, despite the high price.[25][26] This success convinced Gernsback to launch another science-fiction title, and the first issue of Amazing Stories Quarterly appeared in 1928 with a Spring cover date.[26] In the same year Gernsback printed E.E. Smith's first novel, in Amazing, titled The Skylark of Space. It was enormously successful, and on the strength of Smith's Skylark series of novels, and his later Lensman series, Smith became "one of the greatest names, if not the greatest of all" to science fiction readers of the 1930s.[27]

Gernsback's declared goals for Amazing were to educate and to entertain.[28] In the editorial for the first issue he asserted that "Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading – they are also always instructive. They supply knowledge that we might not otherwise obtain – and they supply it in a very palatable form. For the best of these modern writers of scientifiction have the knack of imparting knowledge and even inspiration without once making us aware that we are being taught".[29] It was difficult for Gernsback to find high-quality new material that was both entertaining and met his declared goal of providing scientific information, and the early issues of Amazing contained a high proportion of reprints. He discovered that his readers preferred the fantastical romances of Burroughs and Merritt to the more scientific stories of Verne and Wells, and perhaps in response published Merritt's "The Moon Pool" in the May 1927 issue of Amazing. The story was completely unscientific; Gernsback's introduction to the story claimed that Merritt was introducing a new science, but Ashley comments that Gernsback was simply "looking for an excuse for including such fantastic fiction in the magazine when it did not fit in with his basic creed".[30]

Wonder Stories and Astounding

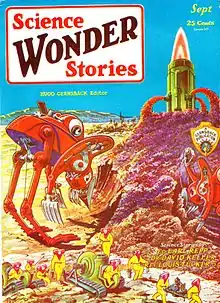

In early 1929 Gernsback went bankrupt, and his magazines were sold to Bergan A. Mackinnon; both Amazing Stories and Amazing Stories Quarterly continued publication under their new ownership, and Sloane remained as editor. Within two months Gernsback had launched two new magazines, Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories. Gernsback still believed in the educational value of science fiction, and contrasted his goals for Air Wonder Stories with the fiction appearing in aviation pulps such as Sky Birds and Flying Aces, which were "purely 'Wild-West'-world war adventure-sky busting"[31] stories, in his words. He planned to fill Air Wonder with "flying stories of the future, strictly along scientific-mechanical-technical lines, full of adventure, exploration and achievement".[31] Both Air Wonder and Science Wonder were edited by David Lasser, who had no prior experience as an editor and who knew little about science fiction, but whose degree from MIT had convinced Gernsback to take him on.[32] Lasser printed work by some popular authors, including Fletcher Pratt, Stanton Coblentz, and David H. Keller,[33] and two of the winners of the contests Gernsback frequently ran subsequently became well known in the field: Raymond Palmer, later the editor of Amazing Stories, and John Wyndham, best known for his 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids.[34] The readership of the two magazines overlapped strongly, most readers being science-fiction fans rather than aviation fans.[35] With these two titles established, Gernsback added Science Wonder Quarterly in October 1929, also edited by Lasser.[36] At the same time Gernsback sent a letter to some of the writers he had already bought stories from, asking for "detective or criminal mystery stories with a good scientific background", and in January 1930 he launched Scientific Detective Monthly, edited by his deputy, Hector Grey, as a new cross-genre title, giving him four magazines in all.[37]

January 1930 also saw the first issue of Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which would go on to become the most influential magazine in the field within a decade. The publisher was William Clayton, a successful publisher of pulp titles. In 1928 Harold Hersey, who by then was working for Clayton, had suggested a new science-fiction magazine to add to the line-up; Clayton was unconvinced, but changed his mind the following year. Astounding's editor, Harry Bates, was uninterested in the educational goals that motivated Gernsback. Bates filled Astounding with adventure stories with minimal scientific content: the stories are generally considered to have been poor quality, and Ashley considers Bates to have been "destroying the ideals of science fiction" with formulaic plots.[38] Gernsback's magazines were infamous for low rates and very slow payment, and Astounding's high rates and quick payment attracted some well-known pulp writers such as Murray Leinster and Jack Williamson.[38] (Asimov later said that in the early industry payment was "not on publication but (the saying went) on lawsuit".)[39] Astounding was also better value for money than its competitors, with both the lowest price and, along with Amazing, the most pages.[40] By mid-1930, Gernsback began to consolidate his magazines, merging Air Wonder with Science Wonder Stories.[41] The combined magazine was titled Wonder Stories, and Science Wonder Quarterly was similarly retitled Wonder Stories Quarterly.[36] At the same time Scientific Detective Monthly was retitled Amazing Detective Tales. Dropping "Science" and "Scientific" from the titles may have been intended to avoid giving readers the impression that these were actually scientific periodicals.[42] Amazing Detective Tales, at least, was not helped by the title change, and after the October issue Gernsback sold the magazine to Wallace Bamber, who published five more issues the following year, though there was no longer any science fiction or fantasy content.[43][44]

.djvu.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, Ghost Stories, the Macfadden title launched in 1926, was suffering declining sales. Hersey, who by 1930 had gone into business as an independent publisher, acquired the title from Macfadden, and started another magazine, Miracle Science and Fantasy Stories, the following year, with Elliott Dold as editor. Neither venture was a success. Miracle ceased publication after only two issues when Dold fell ill, though sales were poor in any case, and Hersey was unable to revive Ghost Stories' fortunes; it was cancelled at the start of 1932.[23][45][46] 1931 also saw Amazing Stories change hands once again; this time it was acquired by Macfadden, whose deep pockets helped insulate Amazing from the effects of the Depression.[47] Sloane continued as editor.[48] Weird Tales was by now well established,[49] but in 1931 Clayton finally gave it some direct competition with Strange Tales, which was also edited by Bates. Like its competitor, Strange Tales frequently published science fiction as well as fantasy; as with Astounding it paid better rates than the competition, and as a result attracted some good writers, including Jack Williamson, whose "Wolves of Darkness", about an invasion by beings from another dimension, is one of its better-remembered stories.[50] Strange Tales did not last long: by late 1932, Clayton was in financial difficulties, and Astounding switched to a bimonthly schedule. Already bimonthly, Strange Tales also reduced its publication frequency. The bulk of Clayton's debts were owed to his printer, which Clayton tried to acquire to prevent it buying out his publishing house, but this proved a disastrous move. He lacked funds to complete the transaction, and was forced to declare bankruptcy. The January 1933 issue of both magazines was intended to be the last, but enough stories remained in inventory to produce one more issue of Astounding, which appeared in March 1933.[51] Street & Smith acquired Astounding and Strange Tales from the sale of Clayton's assets, and relaunched Astounding in October that year. Strange Tales did not reappear; Street & Smith decided to run the stories in Strange Tales' inventory in Astounding instead.[52]

At Wonder Stories, David Lasser remained as editor during the early 1930s,[53] though Wonder Stories Quarterly had to be cut for budget reasons at the start of 1933.[54] Lasser corresponded with his authors to help improve both their level of scientific literacy, and the quality of their writing; Asimov has described Wonder Stories as a "forcing ground", where young writers learned their trade.[55] Lasser was willing to print material that lay outside the usual pulp conventions, such as Eric Temple Bell's The Time Stream and Festus Pragnell's The Green Man of Graypec.[56] Sf critic John Clute gives Lasser credit for making Wonder Stories the best science-fiction magazine of his day,[57] and critics Peter Nicholls and Brian Stableford consider it to be the best of Gernsback's forays into the genre.[58] Despite his success, Lasser was let go in mid-1933, perhaps because he was very well-paid, since there is some evidence of a financial crisis in Gernsback's affairs at the time. Lasser was spending more time working on labor rights, and Gernsback may also have felt he was neglecting his editorial duties. Gernsback replaced Lasser with a 17-year-old science fiction fan, Charles Hornig, at less than a third of Lasser's salary.[59][60][61]

From Gernsback to Campbell

Street & Smith was a well-established pulp publisher, with an excellent distribution network, and the revived Astounding was quickly competitive.[62] It was edited by F. Orlin Tremaine, with assistance from Desmond Hall; both had come to Street & Smith from the wreckage of Clayton.[63] Tremaine was an experienced pulp editor,[63] and Street & Smith gave him a budget of one cent per word, which was better than the competing magazines could pay.[64] In December 1933 Tremaine wrote an editorial calling for "thought variant" stories that contained original ideas and did not simply reproduce adventure themes in a science-fiction context. The early stories identified by Tremaine as "thought variants" were not always particularly original, but it soon became apparent that Tremaine was willing to take risks by publishing stories that would have fallen foul of editorial taboos at other magazines.[65] By the end of 1934, Astounding was the leading science fiction magazine; important stories published that year include Murray Leinster's "Sidewise in Time", the first genre science fiction story to use the idea of alternate history; The Legion of Space, by Jack Williamson; and "Twilight", by John W. Campbell, writing as Don A. Stuart.[66] Within a year Astounding's circulation was estimated at 50,000, about twice that of the competition.[62]

The month after Tremaine announced his "thought variant" policy, Hornig launched his own "New Policy" at Wonder Stories; as with thought variants, the goal was to emphasize originality and bar stories that merely reworked well-worn ideas.[67] Hornig's rates were lower than Astounding's, and sometimes his writers were paid very late, or not at all; despite these handicaps, Hornig managed to find some good material, including Stanley G. Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey", which appeared in the July 1934 Wonder and has been frequently reprinted.[67]

Amazing Stories, and its sister magazine, Amazing Stories Quarterly, both of which had been edited by T. O'Conor Sloane since Gernsback lost control of them in 1929, published little of note during the early 1930s, though Sloane did print the first story by several writers later to become well-known, including John W. Campbell,[68] John Wyndham, and Howard Fast.[48] The Quarterly schedule became irregular in 1932, and it finally ceased publication with the Fall 1934 issue.[69] Weird Tales had survived a bank failure in 1930 that froze most of the magazine's cash,[70] and was continuing to publish well-received material[71]—mostly fantasy and horror, but still including some science fiction.[72] H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors,[49] and Margaret Brundage monopolized the covers for a while, becoming perhaps the best-known artist to work for the magazine; almost all her covers included a nude figure.[73] Virgil Finlay began contributing interior artwork in the mid-1930s;[74] both Finlay and Brundage were very popular with the readers.[73][74]

Gernsback experimented with some companion fiction titles in other genres in 1934, but was unsuccessful, and Wonder Stories' decline proved irreversible. After a failed attempt to persuade his readers to support a subscription-only model, he gave up and sold the magazine to Ned Pines of Standard Magazines in February 1936.[75] It was retitled Thrilling Wonder Stories to fit in with Pines' other titles such as Thrilling Detective, and given to Mort Weisinger to edit, under the supervision of Leo Margulies, Standard's editor-in-chief. The format was left unchanged, but the stories and covers became much more action-oriented. Standard's first issue, dated August 1936, contained stories by several well-known writers, including Ray Cummings, Eando Binder, and Stanley G. Weinbaum, but overall the fiction was unsophisticated compared to what could be found in Astounding. A comic strip, "Zarnak", was tried, but this only lasted eight issues.[76]

Two more science-fiction and fantasy magazines were launched in 1936, but neither lasted beyond the end of the year. Hersey, who had tried the market in 1931 with Miracle, brought out Flash Gordon Strange Adventure Magazine, in an attempt to market pulp magazines to comics fans. Everett Bleiler, a historian of science fiction, describes the stories as "moronic" and "third-rate". Although the magazine was timed to exploit the release of the first Flash Gordon serial, it was a failure, and only one issue appeared.[77][78] The Witch's Tales, a fantasy and horror pulp with ties to a popular radio show of the same name, was slightly more successful, with two issues in November and December 1936. Ashley considers the fiction to have been of reasonable quality, and the magazine's failure may have been because Carwood, the publisher, was small and relatively inexperienced, and may have had weak financing and distribution.[79]

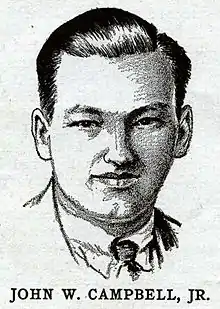

At the end of 1937, Street & Smith promoted Tremaine to assistant editorial director, and his place as editor of Astounding was taken by John W. Campbell. A few months later Street & Smith let Tremaine go, and gave Campbell a freer hand with the magazine. Campbell immediately changed the title from Astounding Stories to Astounding Science-Fiction; his editorial policy was targeted at the more mature readers of science fiction, and he felt that "Astounding Stories" did not convey the right image. He also asked his cover artists to produce more sober and less sensational artwork than had been the case under Tremaine. His most important change was in the expectations he placed on his writers: he asked them to write stories that felt as though they could have been published as non-science fiction stories in a magazine of the future. A reader of the future would not need long explanations for the gadgets in their lives, so Campbell asked his writers to find ways of naturally introducing technology to their stories. He also began running regular scientific fact articles, with the goal of stimulating story ideas.[80] Campbell's approach differentiated Astounding from rivals; Algis Budrys recalled that "it didn't look like an SF magazine" because covers did not show men with ray guns and women with large breasts.[81]

Meanwhile, Bernarr Macfadden's Teck Publications, the owner of Amazing Stories, was running into financial difficulties, and in 1938 the magazine was sold to Ziff-Davis, a Chicago-based publisher.[82] Raymond Palmer, the editor, was a local fan. Under Sloane Amazing had been dull; Palmer wanted it to be fun, and soon transformed the magazine, publishing escapist stories. He was unable to make Amazing into a real rival to Astounding, and Ashley speculates that Bernard G. Davis, who ran the editorial offices of Ziff-Davis, may have instructed Palmer to focus on entertainment rather than on serious science fiction.[83]

During the 1930s the hero pulps were among the most popular titles on the newsstands; these were magazines focused on the adventures of a single character, such as Doc Savage or The Shadow. These often had science-fictional plots, but were not primarily science-fiction or fantasy magazines. One example that was clearly fantasy was Doctor Death, which featured an evil genius who had supernatural powers. It appeared in February 1935 and lasted for only three issues.[84]

Start of the boom

As Campbell began to hit his stride as editor of Astounding, the first boom in science-fiction magazine publishing took off, starting with Marvel Science Stories' appearance in 1938. This was an attempt by publishers Abraham and Martin Goodman to expand their list of titles into science fiction and fantasy. They were known for "weird menace" magazines, a genre incorporating "sex and sadism" into story lines that placed women in danger, usually because of a threat that appeared to be supernatural but was ultimately revealed to be the work of a human villain. For Marvel Science Stories, the Goodmans asked their authors to include more sex in their stories than was usual in the science fiction field; reader reaction was strongly negative to the spicier stories, but the Goodmans kept the magazine going until early 1941, and eventually revived it in 1950 for a few more issues when another science fiction magazine boom began.[85] A companion magazine, Dynamic Science Stories, appeared in February 1939; it was intended to carry longer stories but only lasted two issues.[86]

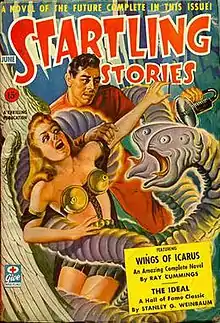

Of more importance to the science-fiction and fantasy genres were several other magazines that debuted in 1939. The first to appear, from Standard Magazines, were Startling Stories and Strange Stories, launched in January and February respectively as companions to Thrilling Wonder Stories; Mort Weisinger edited all three.[87][88] Startling included a lead novel and a "Hall of Fame" reprint section in every issue; the latter was possible because the publisher, Standard Magazines, owned the back catalog of Wonder Stories. At that time no other science fiction pulp was including novels; readers approved, and Startling quickly became one of the most popular science fiction magazines.[87] Strange Stories was launched as a direct competitor to Weird Tales, and the first issue featured many of Weird Tales' most popular authors, including Robert Bloch, August Derleth, Henry Kuttner and Manly Wade Wellman. Bloch, Derleth, and Kuttner were all frequent contributors over the magazine's life, but Ashley regards it as a poor imitation of Weird Tales, fewer of its stories having been anthologized since.[88] At the end of 1938 Weird Tales' owner, B. Cornelius, sold his interest in the magazine to William J. Delaney, the publisher of Short Stories, a general fiction magazine. Delaney's offices were in New York, and Weird Tales' editor, Farnsworth Wright, moved there from Chicago. Delaney made several changes to page count and frequency to try to increase circulation, but none were successful.[89] While this took place, another competitor to Weird Tales was launched, this time by Street & Smith. The new magazine, titled Unknown, was a companion to Astounding and was also edited by John W. Campbell.[90] Campbell's declared policy for the magazine was to "offer fantasy of a quality so far different from that which has appeared in the past as to change your entire understanding of the term";[91] the goal was to bring "the science fiction rationale to fantasy",[92] in Ashley's words. Unknown's first issue was dated March 1939, with L. Ron Hubbard and L. Sprague de Camp soon among the most frequent contributors.[93]

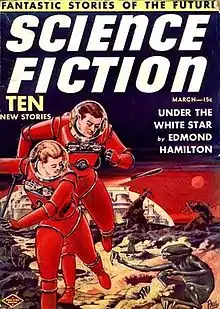

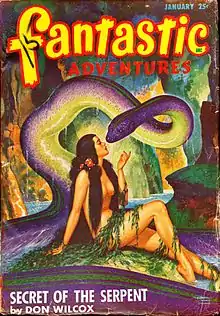

Also in March 1939, a new publisher entered the field: Louis Silberkleit, who had once worked for Gernsback, was the owner of the Blue Ribbon Magazines imprint; he launched Science Fiction, following up with Future Fiction in November that year. Both were edited by Charles Hornig, who had edited Wonder Stories for Gernsback. Silberkleit gave Hornig a very limited budget, so he rarely saw submissions from established writers unless they had already been rejected by the better-paying markets. The result was mediocre fiction.[94] Silberkleit was also slow to pay, which was an additional discouragement to authors deciding where to send their work.[95] In May Ziff-Davis, the publishers of Amazing Stories, joined the fray, with Fantastic Adventures, also edited by Raymond Palmer. As with Amazing, Palmer focused on entertainment, rather than trying to break new ground. Fantastic Adventures was not positioned as a rival to Weird Tales or Unknown, but focused instead on other-worldly adventures in the style of Edgar Rice Burroughs, and soon developed a reputation for whimsical fantasy as well.[96]

The original pulp publisher, the Munsey Company, still had no dedicated science-fiction or fantasy magazine by this time, but frequently published stories in Argosy and All-Story which were clearly within the genre. At the end of 1939 Munsey launched Famous Fantastic Mysteries as a vehicle to reprint these older stories. The editor, Mary Gnaedinger, choose Merritt's "The Moon Pool" and Ray Cummings' "The Girl in the Golden Atom" for the first issue, dated September/October; both titles were likely to attract readers. Gnaedinger engaged Virgil Finlay to do interior illustrations for the second issue, and the magazine was soon successful enough to switch from bimonthly to monthly publication.[97]

The ninth and last new science-fiction or fantasy magazine to appear with a 1939 cover date was Planet Stories, its first issue dated December. The publisher was Fiction House, which had been a successful pulp publisher in the 1920s, though the Depression temporarily closed its doors. After a relaunch in 1934 Fiction House specialized in detective and romance magazines, and Planet was published by its Love Romances, Inc. imprint. The editor, Malcolm Reiss, targeted younger readers, and focused solely on interplanetary fiction, though initially the stories were so weak that Ashley speculates Reiss was forced to start the magazine without enough time to acquire worthwhile material.[98]

Golden Age

When Campbell took over as editor of Astounding, he began to attract some of the major writers in the field, including Clifford D. Simak, L. Ron Hubbard, and Jack Williamson. The launch of Unknown strengthened Campbell's dominance of the field; Henry Kuttner, C.L. Moore, and L. Sprague de Camp contributed to both of Campbell's magazines. As well as developing working relationships with these and other established writers, Campbell discovered and nurtured many new talents. In 1938, he bought Lester del Rey's first story, "The Faithful"; the following year, he published the first stories of A.E. van Vogt, Robert A. Heinlein, and Theodore Sturgeon, along with an early story by Isaac Asimov. All these writers were strongly associated with Astounding over the next few years, and the period starting with Campbell's editorship is sometimes called the Golden Age of Science Fiction.[80][99][100]

Heinlein rapidly became one of the most prolific contributors to Astounding, publishing almost two dozen short stories in the next two years, along with three novels: If This Goes On—, Sixth Column, and Methuselah's Children.[101] In September 1940, van Vogt's first novel, Slan, began serialization; the book was partly inspired by a challenge Campbell laid down to van Vogt that it was impossible to tell a superman story from the point of view of the superman. It proved to be one of the most popular stories Campbell published, and is an example of the way Campbell worked with his writers to feed them ideas and generate the material he wanted to buy.[102] Asimov's "Robot" series began to take shape in 1941, "Reason" and "Liar!" appearing in the April and May issues; as with Slan, these stories were partly inspired by conversations with Campbell.[103] The September 1941 issue included Asimov's short story "Nightfall", one of the most lauded science fiction stories ever written,[103] and in November, Second Stage Lensmen, a novel in Smith's Lensman series, began serialization.[102] The following year saw the beginning of Asimov's "Foundation" stories, with "Foundation" appearing in May and "Bridle and Saddle" in June.[102] Van Vogt's "Recruiting Station", in the March issue, was the first story in his "Weapon Shop" series,[102] described by John Clute as the most compelling of all van Vogt's work.[104]

Many of the stories from the Golden Age have demonstrated enduring popularity, but in the words of Peter Nicholls and Mike Ashley, "the soaring ideas of Golden Age science fiction were all too often clad in an impoverished pulp vocabulary aimed at the lowest common denominator of a mass market".[99] Nicholls and Ashley acknowledge that, despite the uneven literary quality of the stories, the era did produce something extraordinary: "the wild and yearning imaginations of a handful of genre writers – who were mostly very young, and conceptually very energetic indeed – laid down entire strata of science fiction motifs which enriched the field greatly",[99] and they consider that the Golden Age generated "a quantum jump in quality, perhaps the greatest in the history of the genre".[99]

Boom continues

The boom in science fiction magazine publishing continued into 1940, Standard Magazines adding yet another title to Mort Weisinger's portfolio. This was Captain Future, a hero pulp with simple space opera plots in which Captain Future and his friends saved the solar system or the entire universe from a villain. Nearly all the lead novels were written by Edmond Hamilton. It appeared quarterly, the first issue dated Winter 1940.[105] Standard's science fiction titles were unabashedly aimed at young readers, with patronizing gimmicks such as "Sergeant Saturn", who answered readers' letters in all three magazines.[106]

Captain Future was followed by Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories, two new titles from Popular Publications, a well-established pulp publisher. Both magazines were bimonthly, Astonishing's first issue dated February 1940, and Super Science Stories appearing the following month; and both were edited by nineteen-year-old Frederik Pohl—he had shown up at Popular's offices looking for editorial work just as they were considering starting a new magazine, and left as the editor of both new titles. Pohl had a very limited budget, but his contacts with other budding science fiction writers such as Cyril Kornbluth and James Blish meant he was able to find surprisingly good material. Popular paid promptly, which was more than could be said for some of the other publishers, and so despite the low rates Pohl soon began to see submissions that had been rejected by Campbell at Astounding but not sent anywhere else. As a result, he occasionally printed material by some of the Astounding regulars, including "Genus Homo", a collaboration between L. Sprague de Camp and P. Schuyler Miller, and "Lost Legion", by Robert A. Heinlein.[107]

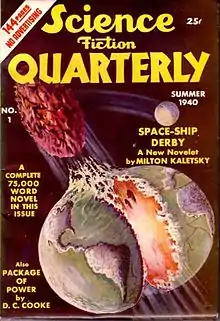

In mid-1940 Louis Silberkleit, who already had two titles on the market (Science Fiction and Future Fiction, both edited by Charles Hornig), added a third, titled Science Fiction Quarterly, with the intention of including a full-length novel in every issue. Silberkleit obtained reprint rights to some of the lead novels from Gernsback's Science Wonder Quarterly that had appeared a decade earlier. The new magazine was added to Hornig's responsibilities, but by the end of the year Hornig had moved to California and all three titles were given to Robert W. Lowndes to edit.[108] Mid-1940 also saw Munsey launch Fantastic Novels, a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries; like Science Fiction Quarterly it was planned as a vehicle for novel-length works, though in this case the novels were reprints from Munsey's backlog.[97]

In December 1940 the first issue of Comet appeared. This saw the return to the field of F. Orlin Tremaine, who had been influential in the mid-1930s when he edited Astounding.[109] The publisher, H-K Publications, was owned by Harold Hersey, who had previously been involved with several failed magazines—The Thrill Book, Ghost Stories, Miracle Science and Fantasy Stories, and Flash Gordon Strange Adventures. Tremaine had a relatively high budget for fiction compared to many of the new magazines, but this may have put Comet under greater financial pressure, and it only survived for five issues, ceasing publication with the July 1941 issue.[109]

Two more magazines appeared in early 1941, Stirring Science Stories and Cosmic Stories, on alternating months, starting in February. These were published by a father and son operating under the name of Albing Publications; they had almost no capital, but persuaded Donald Wollheim to edit the magazine for no salary at all, with no budget for fiction. The plan was to start paying contributors once the magazine was profitable. Like Pohl, Wollheim knew several budding writers who were willing to donate stories, and managed to acquire some good fiction, including "Thirteen O'Clock" and "The City in the Sofa", by Kornbluth, which Ashley describes as "enjoyable tongue-in-cheek fantasies". In the event only six issues appeared in 1941 before Albing failed financially, though Wollheim was able to find another publisher for one more issue of Stirring in March 1942.[110]

The final magazine to launch during 1941 was titled Uncanny Stories, published by the Goodman brothers. Marvel Science Stories ceased publication in 1941, and Uncanny was probably created to use up some remaining stories in its inventory. It was dated the same month as the last issue of Marvel: April 1941, and contained little worthwhile; Ashley comments that the lead story, "Coming of the Giant Germs" by Ray Cummings, was "one of his most appalling stories".[111]

War years

In early 1940, Farnsworth Wright was replaced as editor of Weird Tales by Dorothy McIlwraith, who also edited Short Stories. McIlwraith had no particular expertise in the horror field and, although she was a competent editor, the Wright era is generally considered to have been Weird Tales heyday.[89][112] With Wright's departure, Unknown quickly became the leading magazine in its small field.[71] Unknown acquired a stable of regular writers, many of whom were also appearing in Astounding, and all of whom were comfortable with the rigor that Campbell demanded even of a fantasy plot. Frequent contributors included L. Ron Hubbard, Theodore Sturgeon, and L. Sprague de Camp, who, in collaboration with Fletcher Pratt, contributed three stories about a world where magic operates by logical rules.[113] The stories were later collected as part of Pratt and de Camp's "Incompleat Enchanter" series; John Clute has commented that the title of one of them, "The Mathematics of Magic", is "perfectly expressive of the terms under which magic found easy mention in Unknown".[114] Other stories still regarded as classics include "They" by Heinlein, "Smoke Ghost" by Fritz Leiber, along with several stories in Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series, and "Trouble With Water" by H.L. Gold. Unknown's influence was far-reaching; according to Ashley, the magazine created the modern genre of fantasy,[115] and science-fiction scholar Thomas Clareson suggests that by destroying the genre boundaries between science fiction and fantasy it allowed stories such as Simak's City series to be written. Clareson also proposes that Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, two of the most important and successful science-fiction and fantasy magazines, were direct descendants of Unknown.[116]

In 1941 Weisinger left Standard Magazines to work on the early DC Superman comics,[117] and Oscar J. Friend took over as editor of Startling, Thrilling Wonder, and Captain Future;[118] Strange Stories, which had been Weisinger's idea, was killed off with the January issue.[119] Friend continued the juvenile focus of the three science fiction magazines, and the covers, often by Earle K. Bergey, reinforced the editorial policy: they frequently included women in implausibly revealing spacesuits or wearing Bergey's trademark "brass brassières".[120] Captain Future ceased publication in early 1944,[121] and later that year Friend was replaced as editor by Sam Merwin on both Startling and Thrilling.[122] Planet Stories' first few issues contained little notable fiction, but it improved throughout the war.[98] Leigh Brackett was a regular contributor of planetary romances—melodramatic tales of action and adventure on alien planets and in interplanetary space—and her work had a strong influence on other writers, including Marion Zimmer Bradley. Other well-known writers who sold to Planet included Simak, Blish, Fredric Brown, and Asimov.[123]

At Ziff-Davis, Palmer remained editor of both Fantastic Adventures and Amazing Stories throughout World War II. Much of the material in both magazines came from a group of Chicago-based writers who published under both their own names and various house pseudonyms; among the most prolific were William P. McGivern, David Wright O'Brien, Don Wilcox, and Chester S. Geier.[124][125] The fiction was rarely noteworthy; Ashley describes the wartime Fantastic Adventures as "concentrat[ing] more on quantity than quality, on brash sensationalism than subtlety",[125] though he also comments that it was the most attractive science-fiction or fantasy magazine on newsstands at the time, with covers by J. Allen St. John, Harold McCauley, and Robert Gibson Smith.[125] Similarly, the fiction in Amazing was of uneven quality, though occasionally Palmer obtained good material, including stories by Ray Bradbury, Eric Frank Russell, and John Wyndham.[126]

Few of the new magazines launched during the boom lasted until the end of the war, which brought paper shortages that forced difficult decisions on the publishers.[127] Not every magazine cancellation was because of the war; the usual vicissitudes of magazine publishing also played a role. In 1941, Silberkleit cancelled Science Fiction after 12 issues because of poor sales, merging it with Future Fiction.[128] Two years later Silberkleit ceased publication of both Future and Science Fiction Quarterly when he decided to use the limited paper he could acquire for his western and detective titles instead.[121][129] Both Science Fiction and Future eventually reappeared in the 1950s.[129][130] Fantastic Novels merged with its stablemate, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, in 1941, probably because of wartime difficulties, after only five issues.[131] In 1942 Famous Fantastic Mysteries was sold by Munsey to Popular, who were already the publishers of Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories. Mary Gnaedinger continued as editor, but the editorial policy changed to exclude reprints of stories that had appeared in magazine form. Booklength work was still reprinted, including G. K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday and H. G. Wells' The Island of Dr. Moreau.[132] In the event, Famous Fantastic Mysteries was the only one of Popular's science-fiction and fantasy titles to survive the war. Both Astonishing and Super Science Stories ceased publication in 1943 when Frederik Pohl, the editor of both titles, enlisted in the army; the publisher was having difficulty obtaining enough paper and decided to close the magazines down.[133][134] The same year, paper shortages forced John Campbell to choose between Astounding and Unknown, which had already gone to a bimonthly schedule; he decided to keep Astounding on a monthly schedule, and Unknown ceased publication with the October 1943 issue.[135] Astounding switched to digest format the following month; this was a leading indicator for the direction the field would take, though it would be over a decade before the rest of the field followed suit.[136]

Post-war

Asimov said that "The dropping of the atom bomb in 1945 made science fiction respectable" to the general public.[137] Mainstream magazines began publishing science fiction after the war. Heinlein amazed fans and fellow writers when, Asimov recalled in 1969, "an undiluted science fiction story of his" appeared in The Saturday Evening Post.[138]

Only eight US science-fiction or fantasy magazines survived the war: Astounding Science Fiction, published by Street & Smith; Weird Tales, from Delaney's Short Stories, Inc.; Standard Magazines' Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories; Ziff-Davis's Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures; Popular's Famous Fantastic Mysteries; and Planet Stories, published by Love Romances, Inc.[139] All had been forced to quarterly schedules by the war, except Weird Tales, which was bimonthly, and Astounding,[121] still the leading science fiction magazine.[140] Small science-fiction magazines often lost experienced authors to mass-market publications like Playboy so did not benefit, Asimov said, "from the field's new-won respectability".[138]

Campbell continued to find new writers: William Tenn, H. Beam Piper, Arthur C. Clarke and John Christopher all made their first sales to Astounding in the late 1940s, and he published many stories now regarded as classics, including "Vintage Season" by C.L. Moore, "With Folded Hands ..." by Jack Williamson, Children of the Lens by E.E. Smith, and The Players of Null-A by A.E. van Vogt. The pace of invention which had marked the war years for Astounding was now slackening, however, and in Ashley's words the magazine was now "resting on its laurels".[141] In 1950, Campbell published an article on dianetics by L. Ron Hubbard; this was a psychological theory that would eventually evolve into Scientology, a new religion. Dianetics was denounced as pseudoscience by the medical profession, but to the dismay of many of Astounding's readers it was not until 1951 that Campbell disavowed it.[142]

Sam Merwin, who had taken over from Oscar Friend at Standard Magazines towards the end of the war,[122] abandoned the juvenile approach that had characterized both Startling and Thrilling; he asked Bergey to make his covers more realistic, and started to publish more hard science fiction, including work by Murray Leinster, George O. Smith, and Hubbard. He bought Jack Vance's first sale, "The World Thinker", which appeared in 1945, and published a good deal of material by Ray Bradbury, including several of his Martian Chronicle stories. Some of the highest-profile names from Campbell's stable of Astounding writers sold to Merwin, including van Vogt, Heinlein, and Sturgeon, whose "The Sky Was Full of Ships" appeared in 1947 and was much praised by readers. Other notable stories include Fredric Brown's What Mad Universe, which appeared in 1948, and Kuttner's Valley of the Flame, one of several science-fantasy novels he published in Startling. Writers such as John D. MacDonald, Margaret St. Clair, William Tenn, Arthur C. Clarke, James Blish, and Damon Knight all sold to Merwin, and the net effect was a dramatic improvement in the quality of both magazines, to the point where Ashley suggests that by the late 1940s, Thrilling Wonder, in particular, was a serious challenger to Astounding for the leadership of the field.[143]

Planet Stories also improved dramatically by the end of the decade. Several well-known writers, including Blish, Brown, and Knight, published good material in Planet, but the overall improvement was largely due to the contributions of Bradbury and Leigh Brackett, both of whom set many of their stories on a version of Mars that owed much to the Barsoom of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Brackett, one of Planet's most prolific contributors, developed her style over the 1940s and eventually became the leading exponent of planetary romances. Her series of stories about Eric John Stark, considered by Ashley to be her best work, began in Planet with "Queen of the Martian Catacombs" in the Summer 1949 issue. Bradbury's work for Planet included two of his Martian Chronicles stories, and a collaboration with Brackett, "Lorelei of the Red Mist", which appeared in 1946.[123] Tim Forest, a historian of the pulps, considers Bradbury's work to be Planet's "most important contribution to the genre".[144] The covers were generally simple action scenes, featuring a helpless damsel threatened by a bug-eyed monster,[145] but according to Clute "the content was far more sophisticated than the covers".[146]

Weird Tales had lost much of its unique flavor with the departure of Farnsworth Wright, but in Ashley's view McIlwraith made the magazine more consistent: "though the issues edited by McIlwraith "seldom attain[ed] Wright's highpoints, they also omitted the lows".[147] McIlwraith continued to publish some of Weird Tales most popular authors, such as Fredric Brown and Fritz Leiber,[147] but eliminated sword and sorcery fiction, which Robert E. Howard had popularized under Wright with his stories of Conan, Solomon Kane and Bran Mak Morn.[70][148] August Derleth, who had corresponded with Lovecraft until the latter's death in 1937,[149] continued to send Lovecraft manuscripts to McIlwraith during the 1940s,[150] and at the end of the decade decided to issue a magazine to publicize Arkham House, a publishing venture he had begun in 1939 that reprinted largely from the pages of Weird Tales.[151][152] The title was The Arkham Sampler; Derleth intended it to be a more literary magazine than the current crop of science fiction and fantasy pulps. It published both new and reprint material. Some of the stories were of good quality, including work by Robert Bloch and Lord Dunsany, but it closed down after eight quarterly issues for financial reasons.[151]

At Ziff-Davis, Fantastic Adventures continued as it had during the war, with an occasional noteworthy story such as "Largo", by Theodore Sturgeon, and "I'll Dream of You" by Charles F. Myers.[153] Both Fantastic Adventures and its sister magazine, Amazing Stories, were able to return to monthly publication by late 1947 because of the "Shaver Mystery", a series of stories by Richard Shaver.[154] In the March 1945 issue of Amazing Palmer published a story by Shaver called "I Remember Lemuria". The story, about prehistoric civilizations, was presented by Palmer as a mixture of truth and fiction, and the result was a dramatic boost to Amazing's circulation.[note 5][156] Palmer ran a new Shaver story in every issue, culminating in a special issue in June 1947 devoted entirely to the Shaver Mystery.[156] Amazing soon drew ridicule for these stories and William Ziff ordered Palmer to limit the amount of Shaver-related material in the magazine; Palmer complied, but his interest (and possibly belief) in this sort of material was now significant, and he soon began planning to leave Ziff-Davis. In 1947 he formed Clark Publications, launching Fate the following year, and in 1949 he resigned from Ziff-Davis to edit that and other magazines.[157]

In March 1948, Fantastic Novels reappeared; it had been published by Munsey as a reprint companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries, now owned by Popular, and it took on the same role in its new incarnation. Gnaedinger, the editor, was a fan of Abraham Merritt's work, and the first three issues of the new version included stories by Merritt.[158] Reprints of old classics such as George Allan England's The Flying Legion and Garrett P. Serviss's The Second Deluge constituted most of Fantastic Novels' contents, with some more recent material such as Earth's Last Citadel, by Kuttner and Moore, which had only previously appeared as a serial in Argosy in 1943.[158][159]

Beginning of the digest era

Street & Smith, one of the longest established and most respected magazine publishers, shut down all their pulps in the summer of 1949. The pulps were dying, largely as a result of the success of pocketbooks, and Street & Smith decided to concentrate on their slick magazines. The only survivor of Street & Smith's pulp titles was the digest-format Astounding Science Fiction.[160] By the end of 1955, Fantastic Adventures, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, Thrilling Wonder, Startling Stories, Planet Stories, Weird Tales, and Fantastic Story Quarterly had all ceased publication. Despite the pulps' decline, a few new magazines did appear in pulp format at the end of the 1940s, though these were all short-lived, and several of them focused on reprints rather than new material.[161]

One of the first new post-war titles was Fantasy Book, which appeared in 1947. It was the work of William Crawford, a specialty publisher, and varied between pulp and digest sizes. Crawford ran into problems with distribution and production, and the magazine was never regular, but he produced eight issues over the next four years that included some worthwhile material, most notably Cordwainer Smith's first story, "Scanners Live in Vain", in the January 1950 issue.[162]

Popular had added Fantastic Novels as a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries in 1948; the following year it launched A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine, in an attempt to cash in on Merritt's popularity, and Captain Zero, a science-fictional hero pulp. Both were failures, lasting only five and three issues, respectively. Standard's Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder, both well-regarded by the end of the decade, were joined in 1950 by two reprint magazines. One was Fantastic Story Quarterly, which was intended to carry reprints that were too long to run in Startling's "Hall of Fame" department. This was initially a financial success, and Standard decided to add another title, Wonder Story Annual. Both titles survived into the mid-1950s.[161] Two exceptions to the reprint rule were Future Science Fiction, which Silberkleit brought back as a bimonthly pulp in May 1950, still edited by Lowndes,[129] and Out of This World Adventures, also in pulp format, which combined science-fiction material with a few pages of comics. The publisher, Avon, also launched a romance magazine and a western magazine with the same format, but the experiment was a failure and Out of This World Adventures only lasted for two issues, dated July and December 1950.[161] At the end of 1950 Marvel Science Stories reappeared as the Goodman brothers saw a new boom in science fiction magazines getting under way; it began as a pulp, but changed to a digest the following year. The fiction was of higher quality than in the first incarnation of the magazine, but it lasted less than two years.[163][164]

Although Astounding had been in digest format since 1943, few new digest magazines had been launched since then. One of the first into the fray was Other Worlds, Raymond Palmer's first new science fiction magazine since he had left Ziff-Davis. It appeared in November 1949, and was bimonthly for the first year. Palmer acquired stories by Ray Bradbury, A.E. van Vogt, and Raymond F. Jones, but the overall quality was not high; Ashley characterizes the magazine as "good, but not quite good enough".[165] Howard Browne took over from Palmer as editor of Amazing and Fantastic Adventures, and made strides in improving the quality of both magazines, though much of his impact only became visible after 1950.[166]

In December 1949, Lawrence Spivak, the editor of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, launched The Magazine of Fantasy as a fantasy companion, in digest format. The editors were Anthony Boucher, a well-regarded mystery writer who wrote some science fiction, and J. Francis McComas. It was retitled The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction with the following issue, and four more quarterly issues appeared in 1950. The contents were of the same standard as the fiction that appeared in slick magazines of the day, and it was soon successful.[167] In October 1950 the first issue of Galaxy Science Fiction appeared, edited by H.L. Gold, also in digest format;[168] it too did well, and in the 1950s both magazines became very highly regarded, supplanting Astounding as the leading science-fiction magazines.[169]

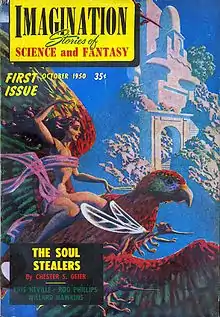

Three more magazines began publication in 1950, all in digest format. The first was Fantasy Fiction, which produced two issues. It included some respectable reprinted material from 1930s issues of Argosy, but none of the new stories were memorable.[170] In October 1950, Raymond Palmer, who had left Ziff-Davis to become a publisher in his own right, launched Imagination. A serious accident in the summer forced him to turn most of the editing work over to Bea Mahaffey, and after two issues he sold the magazine to William Hamling, who kept it going until 1958.[171] The final magazine of the decade was Worlds Beyond, edited by Damon Knight, which appeared in December 1950, and lasted for three monthly issues; the publisher, Hillman Periodicals, decided to scrap the magazine only days after the first issue went on sale. All three issues featured quality work, and many of the stories have been reprinted frequently; Willam Tenn's "Null-P" and C.M. Kornbluth's "The Mindworm" being perhaps the best-known.[172] Knight included material by non-genre writers such as Graham Greene and Rudyard Kipling, along with genre names such as Katherine MacLean and Lester del Rey.[173] Ashley suggests that had Knight been allowed to continue, the magazine would have been a significant contribution to 1950s science fiction.[174]

Doubleday, Simon & Schuster, and other large, mainstream companies began publishing science-fiction books around 1950. They issued fixups and collections of magazine fiction, but also original stories; authors no longer only had magazines as buyers.[175]

List of magazines

This table provides the following information:[176]

- Title. The title that the magazine is usually indexed under. Many magazines changed their title multiple times.

- First and last issue. The year of the first and last issues. If the magazine is still being published, the last issue field is blank.

- Publisher. The name of the publisher(s). Some publishers used multiple imprints; to make it easier to see which magazines were controlled by which individuals or groups, the main person or company behind each publisher is noted where it is not obvious.

- # issues. The number of issues through the end of 1950. If the magazine continued to publish after 1950, the notes column gives the total number of issues.

- New or reprint? Indicates whether the magazine was primarily intended to print new fiction, or reprints. In some cases a magazine printed both, or the focus changed over time; in these cases the table lists whichever was dominant.

- Notes. Among other things, this column notes if a magazine was published in two separate runs.

| Title | First issue | Last issue | Publisher | # issues | New or reprint? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Thrill Book | 1919 | 1919 | Street & Smith | 16 | New | |

| Weird Tales | 1923 | 2014 | Rural, Popular Fiction, Weird Tales (Short Stories) | 256 | New | 23 more issues appeared between 1951 and 1954, and 83 further issues between 1973 and 2014. Popular Fiction should not be confused with Popular Publications. |

| Amazing Stories | 1926 | 2014 | Experimenter (Gernsback), Radio-Science, Teck, Ziff-Davis | 257 | New | Also 355 issues between 1951 and 2014. |

| Amazing Stories Annual | 1927 | 1927 | Experimenter (Gernsback) | 1 | New | |

| Tales of Magic and Mystery | 1927 | 1928 | Personal Arts | 5 | New | |

| Ghost Stories | 1928 | 1932 | Constructive, Good Story (Hersey) | 65 | New | |

| Amazing Stories Quarterly | 1928 | 1934 | Experimenter (Gernsback), Irving Trust, Radio-Science, Teck | 22 | New | An additional 27 issues from 1940–1949 were not a separate magazine; they were rebound copies of Amazing Stories. |

| Air Wonder Stories | 1929 | 1930 | Stellar (Gernsback) | 11 | New | |

| Science Wonder Stories | 1929 | 1930 | Stellar (Gernsback) | 12 | New | |

| Wonder Stories Quarterly | 1929 | 1933 | Stellar (Gernsback) | 14 | Reprint | |

| Astounding Stories | 1930 | Clayton, Street & Smith, Condé Nast, Davis, Dell, Crosstown | 241 | New | 775 subsequent issues as of November 2016. In digest format from the November 1943 issue onwards. | |

| Scientific Detective Monthly | 1930 | 1931 | Techni-Craft (Gernsback), Fiction Publishers | 15 | New | Fiction Publishers should not be confused with Fiction House. |

| Wonder Stories | 1930 | 1936 | Stellar, Continental (both Gernsback) | 66 | New | |

| Miracle Science and Fantasy Stories | 1931 | 1931 | Good Story (Hersey) | 2 | New | |

| Strange Tales | 1931 | 2007 | Clayton | 7 | New | Also three issues 2003–2007. |

| Doctor Death | 1935 | 1935 | Dell | 3 | New | |

| Thrilling Wonder Stories | 1936 | 1954 | Beacon, Better, Standard (all Standard) | 89 | New | A continuation of Wonder Stories. 22 more issues appeared after 1950. |

| The Witch's Tales | 1936 | 1936 | Carwood | 2 | Reprint | |

| Flash Gordon Strange Adventure Magazine | 1936 | 1936 | C.J.H. (Hersey) | 1 | New | |

| Marvel Science Stories | 1938 | 1952 | Postal, Western (both Goodman) | 10 | New | Two runs, 1938–41 and 1950–52; five of the latter issues appeared after 1950. |

| Startling Stories | 1939 | 1955 | Better (Standard), Standard | 65 | New | Also 34 issues between 1951 and 1955. |

| Dynamic Science Stories | 1939 | 1939 | Western (Goodman) | 2 | New | |

| Strange Stories | 1939 | 1941 | Better (Standard) | 13 | New | |

| Unknown | 1939 | 1943 | Street & Smith | 39 | New | |

| Science Fiction Stories | 1939 | 1960 | Blue Ribbon Magazines, Double Action Magazines, Columbia Publications (all Silberkleit) | 12 | New | Two runs, 1939–1941 and 38 issues 1953–1960. |

| Fantastic Adventures | 1939 | 1953 | Ziff-Davis | 101 | New | Also 27 issues 1951–1953. Starting in Winter 1941, Ziff-Davis issued Fantastic Adventures Quarterly; this was not a separate magazine. Instead these were rebound unsold issues of Fantastic Adventures. There were eight of these issues between Winter 1941 and Fall 1943, and another 11 from Summer 1948 to Spring 1951. |

| Famous Fantastic Mysteries | 1939 | 1953 | Munsey, Popular Publications | 66 | Reprint | Also 15 issues 1951–1953. |

| Future Science Fiction | 1939 | 1960 | Blue Ribbon, Double Action, Columbia (all Silberkleit) | 21 | New | Two runs, 1939–43 and 1950–60; 44 of the latter issues appeared after 1950. |

| Planet Stories | 1939 | 1955 | Love Romances (Fiction House) | 45 | New | Also 26 issues 1951–1955. |

| Captain Future | 1940 | 1944 | Standard | 17 | New | |

| Astonishing Stories | 1940 | 1943 | Fictioneers (Popular Publications) | 16 | New | |

| Super Science Stories | 1940 | 1951 | Fictioneers (Popular Publications), Popular Publications | 27 | New | Two runs, 1940–43 and 1949–51; four of the latter issues appeared after 1950. |

| Science Fiction Quarterly | 1940 | 1958 | Double Action, Columbia (both Silberkleit) | 10 | New | Two runs, 1940–43 and 28 issues between 1951 and 1958. |

| Fantastic Novels | 1940 | 1951 | Munsey, Popular Publications | 25 | Reprint | Two runs, 1940–41 and 1948–51; three of the latter issues appeared after 1950. |

| Comet | 1940 | 1941 | H-K (Hersey) | 5 | New | |

| Stirring Science Stories | 1941 | 1942 | Albing, Manhattan Fiction | 4 | New | |

| Cosmic Stories | 1941 | 1941 | Albing | 3 | New | |

| Uncanny Stories | 1941 | 1941 | Manvis (Goodman) | 1 | New | |

| Fantasy Book | 1947 | 1951 | Fantasy Publishing | 7 | New | One more issue appeared in 1951. |

| A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine | 1949 | 1950 | Popular Publications | 5 | Reprint | |

| Other Worlds | 1949 | 1957 | Clark Publishing (Palmer) | 8 | New | Another 37 issues appeared after 1950. |

| Captain Zero | 1949 | 1950 | Recreational Reading (Popular Publications) | 3 | New | |

| The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction | 1949 | Fantasy House, Mercury Press, Spilogale | 5 | New | 723 subsequent issues as of December 2016. | |

| Fantastic Story Quarterly | 1950 | 1955 | Best (Standard) | 3 | Reprint | 20 issues appeared after 1950. |

| Fantasy Fiction | 1950 | 1950 | Curtis Mitchell | 2 | New | |

| Out of This World Adventures | 1950 | 1950 | Avon | 2 | New | |

| Wonder Story Annual | 1950 | 1953 | Better, Best (both Standard) | 4 | Reprint | Three issues appeared after 1950. |

| Imagination | 1950 | 1958 | Clark Publishing (Palmer), Greenleaf Publishing (Hamling) | 2 | New | 61 issues appeared after 1950. |

| Galaxy Science Fiction | 1950 | 1980 | World Editions, Galaxy Publishing, UPD | 3 | New | 252 issues appeared after 1950. Six further issues appeared from a semi-professional publisher in 1994 and 1995. |

| Worlds Beyond | 1950 | 1951 | Hillman Publications | 1 | New | Two more issues appeared in 1951. |

Notes

- The term "science fiction" would not be coined until 1929, but there were other terms used: "scientific romance" and "scientific fiction", for example.[2]

- A pulp magazine was usually 10 x 7 inches, but magazines are often regarded as pulps even if they printed most or all of their run in other sizes – 11.75 x 8 inches is known as large pulp, and sometimes as bedsheet, though this latter term is confusing because "bedsheet" format can also refer to a different, significantly larger, magazine format.[3][4]

- The Thrill Book was initially released in dime-novel format, but switched to pulp with its ninth issue.[10] The typical dime-novel format was saddle-stapled, and either 5 x 7 inches or 8.5 x 11 inches; The Thrill Book was 8 x 10.75 inches.[11]

- The term "different" for this sort of story had been coined by Robert A. Davis, one of the editors at Munsey.[5]

- Palmer claimed the highest circulation of any science-fiction magazine, but del Rey comments that though this may have been true, "Palmer's tendency to magnify everything about the magazine cannot be discounted."[155]

External links

References

Citations

- Stableford (2009), p. 29.

- Nevins (2014), p. 94.

- Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Michael. "Culture : Pulp : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Ashley, Mike. "Culture : Bedsheet : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Murray (2011), p. 11.

- Nevins (2014), pp. 94–95.

- Ashley (1978), p. 52.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 28–35.

- Bleiler (1991), pp. 4–5.

- Ashley (1985h), pp. 661–664.

- Bleiler, Everett F. "Themes : Dime-Novel SF : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 47–49.

- Locke, John. "The Birth of Weird" in The Thing's Incredible! The Secret Origins of Weird Tales (2018), pp. 26–33.

- Locke (2018), p. 135.

- Locke (2018), p. 175.

- Locke (2018), pp. 196-197.

- Weinberg (1985c), pp. 727–728.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 43–44.

- Weinberg (1985c), p. 728.

- Ashley (2000), p. 41.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 48–54.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 62–63.

- Ashley (1985e), pp. 315–317.

- Ashley (1985g), pp. 644–647.

- Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), pp. 560–561.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 54–55.

- Aldiss & Wingrove (1986), p. 209.

- Ashley (2000), p. 50.

- Quoted in Ashley (2000), p. 50).

- Ashley (2000), p. 54.

- Gernsback, editorial in Air Wonder Stories, July 1929, p. 5, quoted in & Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), pp. 541–542.

- Davin (1999), p. 47.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 65–67.

- Davin (1999), p. 39.

- Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), pp. 541–543.

- Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), pp. 578–579.

- Ashley (2004), pp. 158–159.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 69–70.

- Asimov, Isaac (1972). The early Asimov; or, Eleven years of trying. Garden City NY: Doubleday. pp. 25–28.

- Ashley (1978), p. 55.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 70–71.

- Ashley (2000), p. 71.

- Ashley (2000), p. 66.

- Ashley (2000), p. 248.

- Hersey (1937), p. 190.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 71–72.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 76–77.

- Ashley (2000), p. 113.

- Weinberg (1985c), p. 729.

- Weinberg (1985b), pp. 626–627.

- Ashley (2000), p. 76.

- Ashley (2000), p. 82.

- Ashley (2000), p. 260.

- Ashley (2000), p. 77.

- Davin (1999), p. 41.

- Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), p. 589.

- Clute (1995), p. 100.

- Stableford & Nicholls (1993), p. 1346.

- Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), pp. 587–588.

- Davin (1999), p. 94, note 38.

- Davin (1999), p. 70.

- Ashley (2000), p. 85.

- Ashley (2000), p. 84.

- Ashley (2000), p. 87.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 84–85.

- Ashley (2000), p. 86.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 87–88.

- Ashley (2000), p. 67.

- Wolf & Ashley (1985), p. 57.

- Weinberg (1985c), pp. 729–730.

- Ashley, Mike. "Culture : Weird Tales : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- Weinberg (1999), p. 120.

- Weinberg & Everts (1988), pp. 65–66.

- Weinberg (1988), p. 111.

- Ashley (2000), p. 91.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 100–101.

- Bleiler & Bleiler (1998), pp. 575–576.

- Ashley (2000), p. 98–99.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 104–105.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 107–109.

- Pontin, Mark Williams (November–December 2008). "The Alien Novelist". MIT Technology Review.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 114–115.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 115–117.

- Weinberg (1985a), pp. 186–187.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 120–123.

- Marchesani (1985a), pp. 198–199.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 136–138.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 139–140.

- Weinberg (1985c), p. 730.

- Clareson (1985c), p. 699.

- Clareson (1985c), p. 694.

- Ashley (2000), p. 141.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 141–143.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 146–147.

- del Rey (1979), p. 123.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 143–146.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 150–151.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 151–152.

- Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike. "Themes : Golden Age of SF : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Ashley (2000), p. 154.

- Clute, John; Pringle, David. "Authors : Heinlein, Robert A : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Ashley (2000), p. 155.

- Ashley (2000), p. 156.

- Clute, John. "Authors : van Vogt, A E : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 152–153.

- Edwards, Malcolm; Ashley, Mike. "Culture : Startling Stories : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 158–160.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 148–149.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 160–161.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 161–163.

- Ashley (2000), p. 163.

- Ashley (2000), p. 140.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 141–142.

- Clute (1997a), p. 257.

- Ashley (1997a), p. 974.

- Clareson (1985c), p. 697.

- Ashley (2000), p. 123.

- Edwards, Malcolm; Clute, John. "Authors : Friend, Oscar J : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Ashley (2000), p. 139.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 187–188.

- Ashley (2000), p. 175.

- Ashley (2000), p. 261.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 193–194.

- Ashley (2000), p. 176.

- Ashley (1985b), p. 236.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 177–178.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 174–175.

- Ashley (2000), p. 149.

- Ashley (1985d), p. 280.

- Ashley & Thompson (1985), p. 514.

- Clareson (1985b), p. 242.

- Clareson (1985a), pp. 214–215.

- Wolf & Thompson (1985), p. 120.

- Thompson (1985), p. 632.

- Clareson (1985c), p. 695.

- Ashley (2000), p. 158.

- Asimov, Isaac (1969). Nightfall, and other stories. Doubleday. p. 93.

- Asimov, Isaac (1969). Nightfall, and other stories. Doubleday. p. 328.

- Ashley (1976), p. 72.

- Edwards, Malcolm; Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike. "Culture : Astounding Science-Fiction : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 190–193.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 226–229.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 188–190.

- de Forest (2004), p. 76.

- Kyle (1977), p. 96.

- Clute (1995), p. 101.

- Ashley (1997b), p. 1001.

- Clute (1997b), pp. 481–482.

- Joshi (2004), pp. 64–65.

- Joshi (2004), pp. 292–294.

- Eng (1985), pp. 112–114.

- Nicholls, Peter; Edwards, Malcolm. "Culture : Arkham House : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Ashley (1985b), p. 237.

- Ashley (1977), p. 24.

- del Rey (1979), pp. 117–118.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 179–180.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 183–185.

- Clareson (1985b), pp. 242–243.

- Ashley (1985a), p. 107.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 220–221.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 221–223.

- Ashley (2000), pp. 212–213.

- Marchesani (1985b), pp. 398–401.

- Ashley (2005), p. 42.

- Ashley (1985f), p. 460.

- Ashley (2005), pp. 6–7.

- Ashley (2005), pp. 20–23.

- Ashley (2005), pp. 24–25.

- Ashley (2005), p. 20.

- Ashley (1985c), pp. 266–267.

- Ashley (2005), pp. 7–10.

- Casebeer (1985), pp. 768–770.

- Edwards, Malcolm; Ashley, Mike. "Culture : Worlds Beyond : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Ashley (2005), p. 41.

- Budrys, Algis (October 1965). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 142–150.

- Ashley (2000); Ashley (2005); Tymn & Ashley (1985).

Sources

- Aldiss, Brian W.; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. London, England: Victor Gollancz Ltd. ISBN 0-575-03943-4.

- Ashley, Mike (1976) [1975]. The History of the Science Fiction Magazine: Vol. 2: 1936–1945. Chicago, IL: Regnery. ISBN 0-8092-8002-7.

- Ashley, Mike (1977) [1976]. The History of the Science Fiction Magazine: Vol. 3: 1946–1955. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books Inc. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- Ashley, Mike (1978). "Pulps & Magazines". In Holdstock, Robert (ed.). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. London, England: Octopus Books. pp. 50–67. ISBN 0-7064-0756-3.

- Ashley, Mike (1985a). "The Argosy and All-Story". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 103–108. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (1985b). "Fantastic Adventures". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 232–240. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (1985c). "Fantasy Fiction (1950)". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 266–267. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (1985d). "Future Fiction". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 277–284. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.