History of Virginia–Highland

The History of Virginia–Highland, the Intown Atlanta neighborhood, dates back to 1812, when William Zachary bought and built a farm on 202.5 acres (0.819 km2) of land there. At some point between 1888 and 1890 the Nine-Mile Circle streetcar arrived, , making a loop of what are now Ponce de Leon Avenue, North Highland Avenue, Virginia Avenue, and Monroe Drive. Atlantans at first used the line to visit what was then countryside, including Ponce de Leon Springs, but the line also enabled later development in the area. Residential development began as early as 1893 on St. Charles and Greenwood Avenues, must most development took place from 1909 through 1926 — solidly upper-middle class neighborhoods, kept all-white by covenant.

Virginia–Highland, like most intown Atlanta neighborhoods, suffered decline starting in the 1960s as residents moved to the suburbs. Less-affluent residents moved in, some single-family houses were turned into apartments, and crime increased. What could have been the death knell for the neighborhood sounded in the mid-1960s, when the Georgia Department of Transportation proposed building Interstate 485 through the area. Despite this a few middle-class families began renovating homes in the neighborhood. The neighborhoods like others had formed and kept a strong neighborhood association and a strong identity: the area was now known as Virginia–Highland.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the area continue to gentrify, and by 2012 most of the art galleries, antique stores and neighborhood-oriented businesses had given way to a still eclectic collection of retail but which attracted more affluent and less alternative clientele.

Virginia–Highland is today one of the most desirable intown neighborhoods and consistently wins awards for favorite neighborhoods.

Early settlers

In 1812, William Zachary bought and built a farm on 202.5 acres (0.819 km2) of land there. In 1822 he sold his farm to Richard Copeland Todd (1792–1850). Todd's brother-in-law Hardy Ivy settled in 1832 in what is now Downtown Atlanta and the road between their two farms came to be known as Todd Road (a portion of which still exists in Virginia Highland).

"Nine Mile Circle"

In the 1880s, Georgia Railroad executive Richard Peters and real estate developer George Washington Adair organized the Atlanta Street Railway Company.[1] Their first project was the Nine Mile Trolley, which started serving the area sometime between 1888 and 1890 . At first, patrons used this streetcar line to visit "the countryside" outside the city, but the line also enabled later development in the area. Adair built his home at 964 Rupley Drive (still standing and divided into upscale apartments). The iconic curves in the street at the intersections of Virginia Ave. with N. Highland and Monroe are remnants of the trolley line which required gentle curves. The Trolley Square Apartments (now "Virginia Highlands [sic] Apartments") near Virginia and Monroe were built on the site of trolley maintenance facilities.

Residential development

1893 ad for Highland Park

1893 ad for Highland Park 1911 ad for Highland View

1911 ad for Highland View 1916 ad for North Boulevard Park

1916 ad for North Boulevard Park 1922 ad for Virginia Highlands

1922 ad for Virginia Highlands 1922 ad for Virginia Hills

1922 ad for Virginia Hills

The first land to be subdivided in what is now Virginia Highland was Highland Park, between today's Greenwood and Blue Ridge Aves., Barnett St. and N. Highland Ave. However, the majority of the houses and streets in Virginia–Highland were constructed between 1909 and 1926.[2]

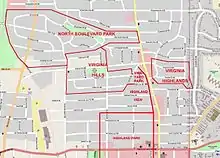

Important subdivisions include:

- Highland View (1911)[3] - Greenwood (north side), Drewry, and Highland View between N. Highland and Barnett; Adair (south side) between N. Highland and Todd Rd.

- Vineyard Park (1911)[3] - built on the grounds of the Adair Mansion - Todd Road (east side), Adair Avenue (north side) and Rupley Drive

- North Boulevard Park (phase one from 1916, phase two from 1926), where Cooledge Avenue was named after E.J. Cooledge, vice-president of the North Boulevard Park Corp., and Orme Circle (And later the eponymous park) were names for A.J. Orme, its secretary-treasurer.

- Virginia Hills (from 1921)

- Virginia Highlands (from 1922) (with an "s" – note that this was before "Virginia Highland" came to refer to the entire neighborhood).

In 1916 the Arc Light Controversy raged between neighbors on Adair Ave. and N. Highland Ave.

Commercial development

Some businesses opened around the intersection of Virginia and N. Highland starting in 1908, with many more opening starting in 1925. At the same time development started in the Atkins Park commercial district around St. Charles. Ave. and N. Highland, including in the present-day Atkins Park Restaurant (1922) which reportedly got what is now Atlanta's oldest liquor license when it became a bar and restaurant in 1927. Between 1928 and 1930, the Howard Dry Cleaning Company and the Phelps Millard Grocery opened, anchoring the Amsterdam and N. Highland business district.

The Samuel N. Inman School, named after the nineteenth-century cotton merchant, was built in 1923. In 1924, fire station 19 was built on N. Highland at Los Angeles Ave.

Streetcar service to Virginia–Highland ended around 1947, along with all of the other trolley lines into and out of central Atlanta.

Decline

Virginia–Highland, like most intown Atlanta neighborhoods, suffered decline starting in the 1960s as residents moved to the suburbs. Less-affluent residents moved in, some single-family houses were turned into apartments, and crime increased. Some businesses closed and were replaced by lower-rent tenants such as pawn shops. Others, such as Moe's and Joe's (which opened in 1947) and Atkins Park Restaurant, stayed open. Many buildings deteriorated.

Threat and defeat of I-485

What could have been the death knell for the neighborhood sounded in the mid-1960s, when the Georgia Department of Transportation proposed building Interstate 485 to connect what is now Freedom Parkway through the neighborhood and to what is now Georgia 400 at Interstate 85. It would have included an interchange at Virginia Avenue where John Howell Memorial Park is today. Despite the I-485 proposal moving forward, a few middle-class families began moving back into the neighborhood, renovating homes.

In Fall 1971, Joseph (Joe) Drolet and others founded the Virginia–Highland Civic Association (VHCA), whose mission was to defeat I-485,[4] and registered the association with the Georgia Secretary of State on August 22, 1972. This was the first time that the area now known as Virginia–Highland was defined as a unit with its current boundaries and name.[5] They along with residents of Stone Mountain, Inman Park, and Morningside finally defeated I-485, and became a political force to be reckoned with. The current Neighborhood Planning Unit (NPU) system is an outgrowth of these events. In 2009, the original north/south freeway (connecting 675 to 400) was again put on GDOT's to-do list, but this time running in a tunnel underneath the neighborhoods, with buildings to vent exhaust fumes and smog above ground.

Between 1972 and 1975, property values increased from 20 to 50 percent. Home ownership levels rose 20 percent. A tour of thirteen renovated homes started in 1972. The Georgia Department of Transportation began selling properties it had acquired for I-485, virtually all of them for infill housing. The 3 acres (12,000 m2) of land on Virginia Avenue where 11 houses had been taken and demolished to make way for a Virginia Avenue exit, however, was finally opened in 1988 as John Howell Memorial Park, in memory of Virginia–Highland resident and anti-freeway activist John Howell, who died from complications of HIV in 1988.

During the 1970s and 1980s the VHCA also worked to improve the city's process of home inspection, to develop a resource network of quality, affordable service providers to aid homeowners in renovation, and to encourage developers to lease renovated commercial buildings "as is" at low rates in order to encourage new and unique businesses, and thus a truly distinct commercial district.

In the early 1980s, Atkins Park restaurant was renovated. Meanwhile, Stuart Meddin bought and renovated the 1925 commercial block at North Highland and Virginia.

In 1988, the turn-of-the-century trolley barns on 5 acres (2.0 ha) on Virginia Avenue on the east side of the BeltLine (today's Virginia Highland Apartments) were torn down despite the City Council and VHCA's attempts to save them. Although previously assuring local residents that he favored saving the historic structures, Mayor Andrew Young then vetoed the resolution, and the Council's vote of 11-3 was not enough to override it. Young cited the discovery of asbestos in the buildings and other hazardous materials on the property.[6][7]

Around 2003, the previously separate St. Charles-Greenwood neighborhood was fully absorbed into the Virginia–Highland neighborhood.[8]

Metro-wide destination

As the neighborhood continued to regentrify, property values increased rapidly; the shops and restaurants became progressively more upscale. Towards the end of the 90s, the neighborhood-oriented character of the business districts gave way to businesses serving patrons from across greater Atlanta.[9] VIrginia–Highland wrestled with traffic and parking issues. Apartments affordable to students became more difficult to find.

A spat between organizers of Summerfest in 2000 and the resulting power-play within the civic association threatened the continuation of the festival, the main source of funding for the VHCA's activities.[10] However, Summerfest did continue as usual in 2001 as one of Atlanta's highest profile neighborhood festivals.

Preservation and balance

In November 2006, the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation added Virginia–Highland to its list of "places in peril" due to an acceleration of teardowns and infill projects by real estate developers and newcomers to the area. However, Virginia–Highland remains one of the most architecturally historic, distinct and vibrant neighborhoods in Atlanta.

Residents, through the VHCA, succeeded in getting the city council to pass zoning legislation prescribing development that fits the scale of the streets, rolling back loose zoning ordinances passed in the 1960s.[11][12] The new zoning also prescribes a maximum number of each type of establishment - restaurants, bars, retail and other types.

The zoning aims to preserve a vibrant mix of enterprises while keeping control noise, parking and traffic issues but also addresses specific problems which came up in 2005-2008:

- Avoiding Virginia Highland suffering the same fate as Buckhead Village, where a large number of bars opened, eventually attracting crime from other areas of the city.

- Fighting a liquor permit for the 700-seat Hilan Theatre.[13]

- Opposing "The Mix@841" project at 841 N. Highland Ave., originally proposed to be 80 feet tall.

In December 2008 the VHCA bought the land for New Highland Park, a small 0.41 acres (0.17 ha) park at N. Highland and St. Charles.

In Autumn 2010, a rash of seven muggings occurred, statistics which were far lower than those of the 1980s when the neighborhood was edgy, but in 2010 shaking up the neighborhood.[14] Partly in response, the local security patrol, FBAC, expanded patrol coverage to the entire neighborhood. Shortly thereafter in Nov. 2010 Charles Boyer was murdered during a mugging, for which the "Jack Boys" were indicted in Jan. 2011.[15] Police continued to step up patrols and since then Virginia Highland has returned to its status as one of Atlanta's lower-crime neighborhoods.[16]

Currently the neighborhood is enjoying adjacent development projects including a new biking and walking trail along the BeltLine from Piedmont Park to Inman Park, as well as the redevelopment of Ponce City Market, the old Sears building, which later became City Hall East. Ponce City Market has become a major multi-use development including a gourmet food hall of national importance and commercial hub. Behind Ponce City Market is the (2011) Historic Fourth Ward Park, founded in 2011.

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-06-02. Retrieved 2012-01-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2012-01-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Metro Atlanta « Georgia Historic Newspapers". Atlnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ("The Interstate That Almost Was", Morningside Lenox Park Association Newsletter, Fall 2003

- "A Rich History - Video". Vahi.org. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Proposal to save trolley barns fails by one vote in council", October 20, 1987, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, Page A/28

- Citing asbestos, Young now wants trolley barns razed", October 17, 1987, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, Page Number: B/1

- "stcharlesgreenwood". Virginia-Highland Civic Association. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Emily Kleine (January 27, 2001). "Virginia–Highland: Classic homes and convivial atmosphere reel 'em in". Creative Loafing.

- Michael Wall, "Will Va-Hi's Summerfest go bye-bye?", Creative Loafing, September 16, 2000

- Thomas Wheatley (October 29, 2008). "Virginia–Highland rezoning aims to repair white flight's wrongs". Creative Loafing.

- "Atlanta City Council minutes, December 1, 2008". Citycouncil.atlantaga.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Mara Shalhoup (July 19, 2006). "A tale of two theaters: intown communities take opposite view on would-be venues". Creative Loafing.

- "7 armed robberies in 7 weeks in VaHi". Fbacvahi.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- FOX. "FOX 5 Atlanta - Breaking Atlanta News, Weather, SKYFOX Traffic - WAGA". WAGA. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Fight Back Against Crime (FBAC) Virginia Highland". Fbacvahi.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.