Horses in World War I

The use of horses in World War I marked a transitional period in the evolution of armed conflict. Cavalry units were initially considered essential offensive elements of a military force, but over the course of the war, the vulnerability of horses to modern weapons such as machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire greatly reduced their utility on the battlefield. This paralleled with the development of tanks, would ultimately replace cavalry in shock tactics role. While the perceived value of the horse in war changed dramatically, horses still played a significant role throughout the war.

All of the major combatants in World War I (1914–1918) began the conflict with cavalry forces. Germany stopped using them on the Western Front soon after the war began, but continued with limited use on the Eastern Front, well into the war. The Ottoman Empire used cavalry extensively during the war. On the Allied side, the United Kingdom used mounted infantry and cavalry charges throughout the war, but the United States used cavalry only briefly. Although not particularly successful on the Western Front, Allied cavalry had some success in the Middle Eastern theatre due to the open nature of the front, allowing a more traditional war of movement, in addition to the lower concentration of artillery and machine guns. Russia used cavalry forces on the Eastern Front but with limited success.

The military used horses mainly for logistical support; they were better than mechanized vehicles at traveling through deep mud and over rough terrain. Horses were used for reconnaissance and for carrying messengers as well as for pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. The presence of horses often increased morale among the soldiers at the front, but the animals contributed to disease and poor sanitation in camps, caused by their manure and carcasses. The value of horses and the increasing difficulty of replacing them were such that by 1917, some troops were told that the loss of a horse was of greater tactical concern than the loss of a human soldier. Ultimately, the blockade of Germany prevented the Central Powers from importing horses to replace those lost, which contributed to Germany's defeat. By the end of the war, even the well-supplied US Army was short of horses.

Conditions were severe for horses at the front; they were killed by artillery fire, suffered from skin disorders, and were injured by poison gas. Hundreds of thousands of horses died, and many more were treated at veterinary hospitals and sent back to the front. Procuring fodder was a major issue, and Germany lost many horses to starvation. Several memorials have been erected to commemorate the horses that died. Artists, including Alfred Munnings, extensively documented the work of horses in the war, and horses were featured in war poetry. Novels, plays and documentaries have also featured the horses of World War I.

Cavalry

Many British tacticians outside of the cavalry units realized before the war that advances in technology meant that the era of mounted warfare was coming to an end. However, many senior cavalry officers disagreed, and despite limited usefulness, maintained cavalry regiments at the ready throughout the war. Scarce wartime resources were used to train and maintain cavalry regiments that were rarely used. The continued tactical use of the cavalry charge resulted in the loss of many troops and horses in fruitless attacks against machine guns.[1]

Early in the war, cavalry skirmishes occurred on several fronts, and horse-mounted troops were widely used for reconnaissance.[2] Britain's cavalry were trained to fight both on foot and mounted, but most other European cavalry still relied on the shock tactic of mounted charges. There were isolated instances of successful shock combat on the Western Front, where cavalry divisions also provided important mobile firepower.[3] Beginning in 1917, cavalry was deployed alongside tanks and aircraft, notably at the Battle of Cambrai, where cavalry was expected to exploit breakthroughs in the lines that the slower tanks could not. This plan never came to fruition due to missed opportunities and the use of machine guns by German forces. At Cambrai, troops from Great Britain, Canada, India and Germany participated in mounted actions.[4] Cavalry was still deployed late in the war, with Allied cavalry troops harassing retreating German forces in 1918 during the Hundred Days Offensive, when horses and tanks continued to be used in the same battles.[5] In comparison to their limited usefulness on the Western Front, "cavalry was literally indispensable" on the Eastern front and in the Middle East.[3]

Great changes in the tactical use of cavalry were a marked feature of World War I, as improved weaponry rendered frontal charges ineffective. Although cavalry was used with good effect in Palestine, at the Third Battle of Gaza and Battle of Megiddo, generally the mode of warfare changed. Tanks were beginning to take over the role of shock combat.[6] The use of trench warfare, barbed wire and machine guns rendered traditional cavalry almost obsolete.[6] Following the war, the armies of the world powers initiated a process of mechanization in earnest, and most cavalry regiments were either converted to mechanized units or disbanded.[7] Historian G.J. Meyer writes that "the Great War brought the end of cavalry".[8] From the Middle Ages into the 20th century, cavalry had dominated battlefields, but from as early as the American Civil War, their value in war was declining as artillery became more powerful, reducing the effectiveness of shock charges. The Western Front in World War I showed that cavalry was almost useless against modern weaponry, and it also reinforced that they were difficult to transport and supply. British cavalry officers, far more than their continental European counterparts, persisted in using and maintaining cavalry, believing that mounted troops would be useful for exploiting infantry breakthroughs, and under the right circumstances would be able to face machine guns. Neither of these beliefs proved correct.[8]

United Kingdom

Britain had increased its cavalry reserves after seeing the effectiveness of mounted Boers during the Second Boer War (1899–1902).[9] Horse-mounted units were used from the earliest days of World War I: on August 22, 1914, the first British shot of the war in France was fired by a cavalryman, Edward Thomas of the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards, near Casteau, during a patrol in the buildup to the Battle of Mons.[10] Within 19 days of Britain beginning mobilization for war, on August 24, 1914, the 9th Lancers, a cavalry regiment led by David Campbell, engaged German troops with a squadron of 4th Dragoon Guards against German infantry and guns. Campbell obeyed his orders to charge, although he believed the more prudent course of action would have been to fight dismounted. The charge resulted in a British loss of 250 men and 300 horses. On September 7, Campbell's troops charged again, this time towards the German 1st Guard Dragoons, another lancer cavalry regiment.[11] In the same year, the British Household Cavalry completed their penultimate operation on horseback—the Allied retreat from Mons.

Upon reaching the Aisne River and encountering the trench system, cavalry was found ineffective. While cavalry divisions were still being formed in Britain, cavalry troops quickly became accustomed to fighting dismounted.[12] Britain continued to use cavalry throughout the war, and in 1917, the Household Cavalry conducted its last mounted charge during a diversionary attack on the Hindenburg Line at Arras. On the orders of Field Marshal Douglas Haig, the Life Guards and the Blues, accompanied by the men of the 10th Hussars, charged into heavy machine gun fire and barbed wire, and were slaughtered by the German defenders; the Hussars lost two-thirds of their number in the charge.[12][13] The last British fatality from enemy action before the armistice went into effect was a cavalryman, George Edwin Ellison, from C Troop 5th Royal Irish Lancers. Ellison was shot by a sniper as the regiment moved into Mons on November 11, 1918.[14]

Despite their lackluster record in Europe, horses proved indispensable to the British war effort in Palestine, particularly under Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, for whom cavalry made up a large percentage of his forces. Most of his mounted troops were not British regular cavalry, but the Desert Mounted Corps, consisting of a combination of Australian, New Zealand, Indian units and English Yeomanry regiments from the Territorial Force, largely equipped as mounted infantry rather than cavalry.[15] By mid-1918, Ottoman intelligence estimated that Allenby commanded around 11,000 cavalry.[16] Allenby's forces routed the Ottoman armies in a running series of battles that included the extensive use of cavalry by both sides. Some cavalry tacticians view this action as a vindication of cavalry's usefulness, but others point out that the Ottoman were outnumbered two to one by late 1918, and were not first-class troops.[15] Horses were also ridden by the British officers of the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps in Egypt and the Levant during the Sinai and Palestine Campaigns.[17]

India

Indian cavalry participated in actions on both the Western and Palestinian fronts throughout the war. Members of the 1st and 2nd Indian Cavalry Divisions were active on the Western Front, including in the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line and at the Battle of Cambrai.[18][19] During the battle of the Somme, the 20th Deccan Horse made a successful, mounted charge, assaulting a German position on Bazentin Ridge. The charge overran the German position. A charge by the 5th (Mhow) Cavalry Brigade of the 1st Division ended successfully at the Battle of Cambrai despite being against a position fortified by barbed wire and machine guns. Such successful endings were unusual occurrences during the war.[20] Several Indian cavalry divisions joined Allenby's troops in the spring of 1918 after being transferred from the Western Front.[16]

Canada

When the war began, Lord Strathcona's Horse, a Canadian cavalry regiment, was mobilized and sent to England for training. The regiment served as infantry in French trenches during 1915, and were not returned to their mounted status until February 16, 1916. In the defense of the Somme front in March 1917, mounted troops saw action, and Lieutenant Frederick Harvey was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions. Canadian cavalry generally had the same difficulties as other nations in breaking trench warfare deadlocks and were of little use on the front lines. However, in the spring of 1918, Canadian cavalry was essential in halting the last major German offensive of the war.[21] On March 30, 1918, Canadian cavalry charged German positions in the Battle of Moreuil Wood, defeating a superior German force supported by machine gun fire.[22] The charge was made by Lord Strathcona's Horse, led by Gordon Flowerdew, later posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions during the charge. Although the German forces surrendered,[21] three-quarters of the 100 cavalry participating in the attack were killed or wounded in the attack against 300 German soldiers.[22][23]

Australia and New Zealand

The Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division (known as the ANZAC Mounted Division) was formed in Egypt in 1916, after the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was disbanded. Comprising four brigades, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Australian Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade. All had fought at Gallipoli dismounted. In August the division's dynamic capabilities were effectively combined with the static 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division at the Battle of Romani, where they repelled an attempted Ottoman attack on the Suez Canal. This victory stopped the advance of Kress von Kressenstein's Expeditionary Force (3rd Infantry Division and Pasha I formation) towards the Suez Canal and forced his withdrawal under pressure. An Ottoman garrison at Magdhaba was defeated in December 1916 by the division with the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade attached and the other major Ottoman fortification at Rafah was captured in January 1917. They participated mounted in the First Battle of Gaza in March, and the Third Battle of Gaza (including the Battle of Beersheba) in October 1917. They attacked dismounted in the Second Battle of Gaza in April 1917. In 1918, the ANZAC and Australian Mounted Divisions, along with the Yeomanry Mounted Division in the Desert Mounted Corps, conducted two attacks across the Jordan River to Amman in March, then moved on to Es Salt in April. The Australian Mounted Division were armed with swords mid year, and as part of the Battle of Megiddo captured Amman (capturing 10,300 prisoners), Nazareth, Jenin and Samakh in nine days. After the Armistice they participated in the reoccupation of Gallipoli in December.[24][25]

The ANZAC and Australian Mounted Divisions carried rifles, bayonets and machine guns, generally using horses as swift transport and dismounting to fight.[26][note 1] Troops of four men were organised, so that three were fighting while the fourth held the horses.[28] Sometimes they fought as mounted troops: at the Battle of Beersheba during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1917, the Australian Mounted Division's 4th Light Horse Brigade made what is sometimes called "the last successful cavalry charge in history", when two regiments successfully overran Ottoman trenches.[29][30] They formed up over a wide area, to avoid offering a target for enemy artillery, and galloped 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) into machine gun fire, equipped only with rifles and bayonets. Some of the front ranks fell, but most of the brigade broke through, their horses jumping the trenches into the enemy camp. Some soldiers dismounted to fight in the trenches, while others raced on to Beersheba, to capture the town and its vital water supplies.[31] The charge was "instrumental in securing Allenby's victory [in Palestine]".[3]

The Australians primarily rode Waler horses.[28] The English cavalry officer, Lieutenant Colonel RMP Preston DSO, summed up the animals' performance in his book, The Desert Mounted Corps:

... (November 16th, 1917) The operations had now continued for 17 days practically without cessation, and a rest was absolutely necessary especially for the horses. Cavalry Division had covered nearly 170 miles ... and their horses had been watered on an average of once in every 36 hours ... The heat, too, had been intense and the short rations, 9 1⁄2 lb of grain per day without bulk food, had weakened them greatly. Indeed, the hardship endured by some horses was almost incredible. One of the batteries of the Australian Mounted Division had only been able to water its horses three times in the last nine days—the actual intervals being 68, 72 and 76 hours respectively. Yet this battery on its arrival had lost only eight horses from exhaustion, not counting those killed in action or evacuated wounded ... The majority of horses in the Corps were Walers and there is no doubt that these hardy Australian horses make the finest cavalry mounts in the world ...[32]

Continental Europe

—An American observer of French cavalry tactics, 1917[33]

.jpg.webp)

Before the war began, many continental European armies still considered the cavalry to hold a vital place in their order of battle. France and Russia expanded their mounted military units before 1914. Of the Central Powers, Germany added thirteen regiments of mounted riflemen, Austria–Hungary expanded their forces,[34] and the Bulgarian army also readied the cavalry in their army.[35] When the Germans invaded in August 1914, the Belgians had one division of cavalry.[36]

French cavalry had similar problems with horses on the Western Front as the British,[13] although the treatment of their horses created additional difficulties. Opinion generally was that the French were poor horsemen: "The French cavalryman of 1914 sat on his horse beautifully, but was no horsemaster. It did not occur to him to get off his horse's back whenever he could, so there were thousands of animals with sore backs ...".[37] One French general, Jean-François Sordet, was accused of not letting horses have access to water in hot weather.[37][note 2] By late August 1914, a sixth of the horses in the French cavalry were unusable.[38] The French continued to eschew mounted warfare when in a June 1918 charge by French lancers the horses were left behind and the men charged on foot.[13]

Russia possessed thirty-six cavalry divisions when it entered the war in 1914, and the Russian government claimed that its horsemen would thrust deep into the heart of Germany. Although Russian mounted troops entered Germany, they were soon met by German forces. In the August 1914 Battle of Tannenberg, troops led by German Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and Lieutenant-General Erich Ludendorff surrounded the Russian Second Army and destroyed the mounted force of Don Cossacks that served as the special guard of Russian General Alexander Samsonov.[39] Other Russian cavalry units successfully harassed retreating Austro-Hungarian troops in September 1914, with the running battle eventually resulting in the loss of 40,000 of the 50,000 men in the Austro-Hungarian XIV Tyrolean Corps, which included the 6th Mounted Rifle Regiment.[40] Transporting cavalry created a hardship for the already strained Russian infrastructure, as the great distances they needed to be moved meant that they had to be transported by train. Approximately the same number of trains (about 40) were required to transport a cavalry division of 4,000 as to transport an infantry division of 16,000.[39]

The cavalries of the Central Powers, Germany and Austria–Hungary, faced the same problems with transport and the failure of tactics as the Russians.[41] Germany initially made extensive use of cavalry, including a lance-against-lance battle with the British in late 1914,[11] and an engagement between the British 1st Cavalry Brigade and the German 4th Cavalry Division in the lead-up to the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914. That battle ended "decidedly to the disadvantages of the German cavalry", partially due to the use of artillery by the accompanying British L Battery of horse artillery.[42] The Germans stopped using cavalry on the Western Front not long after the beginning of the war, in response to the Allied Forces' changing battle tactics, including more advanced weaponry.[41] They continued to use cavalry to some extent on the Eastern Front, including probes into Russian territory in early 1915.[43] The Austrians were forced to stop using cavalry because of large-scale equipment failures; Austrian military saddles were so poorly designed as to rub the skin off the back of any horse not already hardened to the equipment from parade ground practice; only a few weeks into the war half of all Austrian cavalry mounts were disabled, and the rest nearly so.[41]

Ottoman Empire

In 1914, the Ottoman Empire began the war with one cavalry regiment in their armed forces and four reserve regiments (originally formed in 1912) under the control of the Third Army. These reserve regiments were composed of Kurds, rural Turks and a few Armenians.[44] The performance of the reserve divisions was poor, and in March 1915 the forces that survived were turned into two divisions totalling only two thousand men and seventy officers. Later that month, the best regiments were consolidated into one division and the rest disbanded. Nonetheless, cavalry was used by Ottoman forces throughout 1915 in engagements with the Russians,[45] and one cavalry unit even exchanged small arms fire with a submarine crew in the Dardanelles in early 1915.[46] Ottoman cavalry was used in engagements with the Allies, including the Third Battle of Gaza in late 1917. In this battle, both sides used cavalry forces as strategic parts of their armies.[47] Cavalry continued to be involved in engagements well into 1918, including in conflicts near the Jordan River in April and May that year, which the Ottomans called the First and Second Battles of Jordan, part of the lead-up to the Battle of Megiddo. By September 1918, regular army cavalry forces were stationed throughout the Middle Eastern front, and the only remaining operationally ready reserve forces in the Ottoman military were two cavalry divisions, one formed after the initial problems in 1915.[16]

United States

By 1916, the United States Cavalry consisted of 15,424 members organized into 15 regiments, including headquarters, supply, machine-gun and rifle troops.[48] Just before formally joining the war effort, the US had gained significant experience in 1916 and 1917 during the Pancho Villa Expedition in Mexico, which helped to prepare the US Cavalry for entry into World War I. In May 1917, a month after the US declaration of war, the National Defense Act went into effect, creating the 18th through the 25th US Cavalry regiments, and later that month, twenty more cavalry regiments were created. However, British experiences during the first years of the war showed that trench warfare and weapons that included machine guns and artillery made cavalry warfare impractical. Thus, on October 1, eight of the new cavalry regiments were converted to field artillery regiments by order of Congress, and by August 1918, twenty National Army horse units were converted to thirty-nine trench mortar and artillery batteries. Some horse units of the 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 15th Cavalry regiments accompanied the US forces in Europe. The soldiers worked mainly as grooms and farriers, attending to remounts for the artillery, medical corps and transport services. It was not until late August 1918 that US cavalry entered combat. A provisional squadron of 418 officers and enlisted men, representing the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, and mounted on convalescent horses, was created to serve as scouts and couriers during the St. Mihiel Offensive. On September 11, 1918, these troops rode at night through no man's land and penetrated five miles behind German lines. Once there, the cavalry was routed and had to return to Allied territory. Despite serving through the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, by mid-October the squadron was removed from the front with only 150 of its men remaining.[49]

Logistical support

Horses were used extensively for military trains. They were used to pull ambulances, carry supplies and ordnance. At the beginning of the war, the German army depended upon horses to pull its field kitchens, as well as the ammunition wagons for artillery brigades.[50] The Royal Corps of Signals used horses to pull cable wagons, and the promptness of messengers and dispatch riders depended on their mounts. Horses often drew artillery and steady animals were crucial to artillery effectiveness.[51] The deep mud common in some parts of the front, caused by damaged drainage systems flooding nearby areas, made horses and mules vital, as they were the only means of getting supplies to the front and guns moved from place to place.[51] After the April 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge, one Canadian soldier recalled, "the horses were up to their bellies in mud. We'd put them on a picket line between the wagon wheels at night and they'd be sunk in over their fetlocks the next day. We had to shoot quite a number."[52]

Thousands of horses were employed to pull field guns; six to twelve horses were required to pull each gun.[53] During the Battle of Cambrai, horses were used to recover guns captured by the British from no man's land. In one instance, two teams of sixteen horses each had their hooves, tack and pulling chains wrapped to reduce noise. The teams and their handlers then successfully pulled out two guns and returned them to British lines, the horses jumping a trench in the process and waiting out an artillery barrage by German troops on the road they needed to take.[54]

Dummy horses were sometimes used to deceive the enemy into misreading the location of troops.[53] They were effectively used by Allenby during his campaigns in the east, especially late in the war.[55][56] Evidence exists that the Germans used horses in their experimentations with chemical and biological warfare. German agents in the US are suspected of infecting cattle and horses bound for France with glanders, a disease which can fatally spread to humans; similar tactics were used by the Germans against the Russians, causing breakdowns in their ability to move artillery on the Eastern Front.[57]

The value of horses was known to all. In 1917 at the Battle of Passchendaele, men at the front understood that "at this stage to lose a horse was worse than losing a man because after all, men were replaceable while horses weren't."[58]

Procurement

Allied forces

To meet its need for horses, Britain imported them from Australia, Canada, the US, and Argentina, and requisitioned them from British civilians. Lord Kitchener ordered that no horses under 15 hands (60 inches, 152 cm) should be confiscated, at the request of many British children, who were concerned for the welfare of their ponies. The British Army Remount Service, in an effort to improve the supply of horses for potential military use, provided the services of high quality stallions to British farmers for breeding their broodmares.[53] The already rare Cleveland Bay was almost wiped out by the war; smaller members of the breed were used to carry British troopers, while larger horses were used to pull artillery.[9] New Zealand found that horses over 15.2 hands (62 inches, 157 cm) fared worse than those under that height. Well-built Thoroughbreds of 15 hands and under worked well, as did compact horses of other breeds that stood 14.2 to 14.3 hands (58 to 59 inches, 147 to 150 cm). Larger crossbred horses were acceptable for regular work with plentiful rations, but proved less able to withstand short rations and long journeys. Riflemen with tall horses suffered more from fatigue, due to the number of times they were required to mount and dismount the animals. Animals used for draught work, including pulling artillery, were also found to be more efficient when they were of medium size with good endurance than when they were tall, heavy and long-legged.[59]

The continued resupply of horses was a major issue of the war. One estimate puts the number of horses that served in World War I at around six million, with a large percentage of them dying due to war-related causes.[60] In 1914, the year the war began, the British Army owned only about 25,000 horses. This shortfall required the US to help with remount efforts, even before it had formally entered the war.[61] Between 1914 and 1918, the US sent almost one million horses overseas, and another 182,000 were taken overseas with American troops. This deployment seriously depleted the country's equine population. Only 200 returned to the US, and 60,000 were killed outright.[60] By the middle of 1917, Britain had procured 591,000 horses and 213,000 mules, as well as almost 60,000 camels and oxen. Britain's Remount Department spent £67.5 million on purchasing, training and delivering horses and mules to the front. The British Remount Department became a major multinational business and a leading player in the international horse trade, through supplying horses to not only the British Army but also to Canada, Belgium, Australia, New Zealand, Portugal, and even a few to the US. Shipping horses between the US and Europe was both costly and dangerous; American Expeditionary Force officials calculated that almost seven times as much room was needed per ton for animals than for average wartime cargo, and over 6,500 horses and mules were drowned or killed by shell fire on Allied ships attacked by the Germans.[61] In turn, New Zealand lost around 3 percent of the nearly 10,000 horses shipped to the front during the war.[62]

Due to the high casualty rates, even the well-supplied American army was facing a deficit of horses by the final year of the war. After the American First Army, led by General John J. Pershing, pushed the Germans out of the Argonne Forest in late 1918, they were faced with a shortage of around 100,000 horses, effectively immobilizing the artillery. When Pershing asked Ferdinand Foch, Marshal of France, for 25,000 horses, he was refused. It was impossible to obtain more from the US, as shipping space was limited, and Pershing's senior supply officer stated that "the animal situation will soon become desperate." The Americans, however, fought on with what they had until the end of the war, unable to obtain sufficient supplies of new animals.[63]

Central Powers

Before World War I, Germany had increased its reserves of horses through state-sponsored stud farms (German: Remonteamt) and annuities paid to individual horse breeders. These breeding programs were designed specifically to provide high-quality horses and mules for the German military. These efforts, and the horse-intensive nature of warfare in the early 20th century, caused Germany to increase the ratio of horses to men in the army, from one to four in 1870 to one to three in 1914. The breeding programs allowed the Germans to provide all of their own horses at the beginning of the war.[61] Horses were considered army reservists; owners had to register them regularly, and the army kept detailed records on the locations of all horses. In the first weeks of the war, the German army mobilized 715,000 horses and the Austrians 600,000. Overall, the ratio of horses to men in Central Powers nations was estimated at one to three.[64][note 3]

The only way Germany could acquire large numbers of horses after the war began was by conquest. More than 375,000 horses were taken from German-occupied French territory for use by the German military. Captured Ukrainian territory provided another 140,000.[61] The Ardennes was used to pull artillery for the French and Belgian armies. Their calm, tolerant disposition, combined with their active and flexible nature, made them an ideal artillery horse.[65] The breed was considered so useful and valuable that when the Germans established the Commission for the Purchase of Horses in October 1914 to capture Belgian horses, the Ardennes was one of two breeds specified as important, the other being the Brabant.[51] The Germans were not able to capture the horses belonging to the Belgian royal family, as they were successfully evacuated, although they captured enough horses to disrupt Belgian agriculture and breeding programs. Horses used for the transport of goods were also taken, resulting in a fuel crisis in Belgium the next winter as there were no horses to pull coal wagons. The Germans sold some of their captured horses at auction.[66] Prevented by the Allies from importing remounts, the Germans ultimately ran out of horses, making it difficult for them to move supplies and artillery, a factor contributing to their defeat.[53]

Casualties and upkeep

Battle losses of horses were approximately 25 percent of all war-related equine deaths between 1914 and 1916. Disease and exhaustion accounted for the remainder.[61] The highest death rates were in East Africa, where in 1916 alone deaths of the original mounts and remounts accounted for 290% of the initial stock numbers, mainly due to infection from the tsetse fly.[note 4] On average, Britain lost about 15 percent (of the initial military stock) of its animals each year of the war (killed, missing, died or abandoned), with losses at 17 percent in the French theatre. This compared to 80 percent in the Crimean War, 120 percent in the Boer War and 10 percent in peacetime.[61] During some periods of the war, 1,000 horses per day were arriving in Europe as remounts for British troops, to replace horses lost. Equine casualties were especially high during battles of attrition, such as the 1916 Battle of Verdun between French and German forces. In one day in March, 7,000 horses were killed by long-range shelling on both sides, including 97 killed by a single shot from a French naval gun.[67] By 1917, Britain had over a million horses and mules in service, but harsh conditions, especially during winter, resulted in heavy losses, particularly amongst the Clydesdale horses, the main breed used to haul the guns. Over the course of the war, Britain lost over 484,000 horses, one horse for every two men.[68] A small number of these, 210, were killed by poison gas.[36]

Feeding horses was a major issue, and horse fodder was the single largest commodity shipped to the front by some countries,[69] including Britain.[70] Horses ate around ten times as much food by weight as a human, and hay and oats further burdened already overloaded transport services. In 1917, Allied operations were threatened when horse feed rations were reduced after German submarine activity restricted supplies of oats from North America, combined with poor Italian harvests. The British rationed hay and oats, although their horses were still issued more than those from France or Italy. The Germans faced an even worse fodder crisis, as they had underestimated the amount of food they needed to import and stockpile before the beginning of the war. Sawdust was mixed with food during times of shortage to ease animals' sense of hunger, and many animals died of starvation. Some feed was taken from captured territories on the Eastern Front, and more from the British during the advances of the 1918 spring offensive.[61]

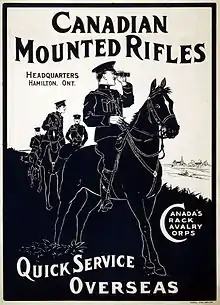

Animals bolstered morale at the front, due to the soldiers' affection for them.[51] Some recruitment posters from World War I showcased the partnership between horse and man in attempts to gain more recruits.[53] Despite the boost in morale, horses could also be a health hazard for the soldiers, mainly because of the difficulty of maintaining high levels of hygiene around horses, which was especially noted in camps in Egypt.[71] Horse manure was commonplace in the battle and staging areas on several fronts, creating breeding grounds for disease-carrying insects. Manure was supposed to be buried, but fast-moving battle conditions often made this impossible. Sanitation officers were responsible for the burial of horse carcasses, among other duties.[72]

Many horses died as a result of the conditions at the front—of exhaustion, drowning, becoming mired in mud and falling in shell holes. Other horses were captured after their riders were killed. Horses also endured poor feeding and care, poison gas attacks that injured their respiratory systems and skin, and skin conditions such as mange. When gas warfare began in 1915, nose plugs were improvised for the horses to allow them to breathe during attacks.[53] Later, several types of gas masks were developed by both the Central and Allied nations,[73][74] although horses often confused them with feedbags and destroyed them. Soldiers found that better-bred horses were more likely to suffer from shell shock and act up when exposed to the sights and sounds of war than less-well-bred animals, who often learned to lie down and take cover at the sound of artillery fire. Veterinary hospitals were established to assist horses in recovering from shell shock and battle wounds, but thousands of equine corpses still lined the roads of the Western Front.[53] In one year, 120,000 horses were treated for wounds or disease by British veterinary hospitals alone. Ambulances and field veterinary hospitals were required to care for the horses, and horse trailers were first developed for use on the Western Front as equine ambulances.[60] Disease was also a major issue for horses at the front, with equine influenza, ringworm, sand colic, sores from fly bites, and anthrax among the illnesses that affected them.[75] British Army Veterinary Corps hospitals treated 725,216 horses over the course of the war, successfully healing 529,064.[36] Horses were moved from the front to veterinary hospitals by several methods of transportation, including on foot, by rail and by barge.[76] During the last months of the war, barges were considered ideal transportation for horses suffering wounds from shells and bombs.[77]

When the war ended, many horses were killed due to age or illness, while younger ones were sold to slaughterhouses or to locals, often upsetting the soldiers who had to give up their beloved mounts.[53] There were 13,000 Australian horses remaining at the end of World War I, but due to quarantine restrictions, they could not be shipped back to Australia. Two thousand were designated to be killed, and the remaining 11,000 were sold, most going to India as remounts for the British Army.[28] Of the 136,000 horses shipped from Australia to fighting fronts in the war, only one, Sandy, was returned to Australia.[78][note 5] New Zealand horses were also left behind; those not required by the British or Egyptian armies were shot to prevent maltreatment by other purchasers.[79] The horses left behind did not always have good lives—the Brooke Trust was established in 1930 when a young British woman arrived in Cairo, only to find hundreds of previously Allied-owned horses living in poor conditions, having been sold to Egyptians after the cessation of the war. In 1934, the Old War Horse Memorial Hospital was opened by the trust, and is estimated to have helped over 5,000 horses that had served in World War I; as of 2011, the hospital continues to serve equines in the Cairo area.[80]

Legacy

The horse is the animal most associated with the war, and memorials have been erected to its service, including that at St. Jude on the Hill, Hampstead, which bears the inscription "Most obediently and often most painfully they died – faithful unto death."[51] The Animals in War Memorial in London commemorates animals, including horses, that served with the British and their allies in all wars. The inscription reads: "Animals In War. This monument is dedicated to all the animals that served and died alongside British and allied forces in wars and campaigns throughout time. They had no choice."[81] In Minneapolis, a monument by Lake of the Isles is dedicated to the horses of the Minnesota 151st Field Artillery killed in battle during World War I.[82]

The men of the Australian Light Horse Brigade and New Zealand Mounted Rifles who died between 1916 and 1918 in Egypt, Palestine and Syria are commemorated by the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial, or Light Horse Memorial, on Anzac Parade, in Canberra, Australia.[83] The original version of this monument was in Port Said in Egypt, and was mostly destroyed during the 1956 Suez War.[84] A piece from the original memorial, a shattered horse's head, was brought back to Australia and used as part of a new statue in the A is for Animals exhibition honoring animals who have served with the Australian military. The exhibition also contains the preserved head of Sandy, the only horse to return to Australia after the war.[84][85]

War artist Alfred Munnings was sent to France in early 1918 as an official war artist with the Canadian Cavalry Brigade. The Canadian Forestry Corps invited Munnings to tour their work camps in France after seeing some of his work at the headquarters of General Simms, the Canadian representative. He produced drawings, watercolors, and paintings of their work, including Draft Horses, Lumber Mill in the Forest of Dreux in 1918.[86] Forty-five of his paintings were displayed at the Canadian War Records Exhibition at the Royal Academy, many of which featured horses in war.[87][note 6] Numerous other artists created works that featured the horses of World War I, including Umberto Boccioni with Charge of the Lancers[88] and Terence Cuneo with his celebrated postwar painting of the saving of the guns at Le Cateau during the Retreat from Mons.[89] During World War I, artist Fortunino Matania created the iconic image Goodbye Old Man that would be used by both British and American organizations to raise awareness of the suffering of animals affected by war. The painting was accompanied by a poem, The Soldiers Kiss, that also emphasized the plight of the horse in war.[90][91]

Writing poetry was a means of passing the time for soldiers of many nations, and the horses of World War I figured prominently in several poems.[92][93] In 1982, Michael Morpurgo wrote the novel War Horse, about a cavalry horse in the war. The book was later adapted into a successful play of the same name, and also into a screenplay, with the movie, released on December 25, 2011 in the United States.[94]

See also

Notes

- The Action of Ayun Kara on 14 November 1917 was a particularly good example of this fighting style.[27]

- By September 1914, with battered men and horses, having abandoned a crucial position in the First Battle of the Marne, Sordet was relieved of his command.[37]

- The Russian military topped both Germany and Austria by gathering over a million horses in August 1914.[64]

- This number was higher than 100 percent because additional horses were requisitioned and sent to the front, where they had a high attrition rate.

- Sandy was the horse of Sir William Bridges, a Major General killed at Gallipoli. In October 1917, Australia's Minister for Defence Senator George Pearce asked that Sandy be returned to Australia. After three months of quarantine, Sandy was allowed to return to Australia.[78]

- Among Munnings' works was The Charge of Flowerdew's Squadron which depicted the Canadian cavalry charge at the Battle of Moreuil Wood.

Citations

- Ellis, Cavalry, pp. 174–76

- Willmott, First World War, p. 46

- Holmes, Military History, p. 188

- Hammond, Cambrai 1917, pp. 69, 450–51

- "Cavalry and Tanks at Arras, 1918". Canadian War Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-04-24. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- Carver, Britain's Army in the 20th Century, p. 123

- Carver, Britain's Army in the 20th Century, pp. 154–57

- Meyer, A World Undone, p. 264

- Dent, Cleveland Bay Horses, pp. 61–64

- "The First Shot: 22 August 1914". World Wars in-depth. BBC. November 5, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- "Sir David Graham Muschet ('Soarer') Campbell". Centre for First World War Studies, University of Birmingham. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- Braddon, All the Queen's Men, pp. 187–88

- Ellis, Cavalry, p. 176

- Fowler, Simon, ed. (December 2008). "Voices of the Armistice – The unluckiest man". Ancestors. The National Archives/Wharncliffe Publishing Limited (76): 45.

- Ellis, Cavalry, pp. 176–77

- Erickson, Ordered to Die, pp. 195–97

- McPherson, et al., The man who loved Egypt, pp. 184–86

- Baker, Chris. "The 1st Indian Cavalry Division in 1914–1918". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- Baker, Chris. "The Mounted Divisions of 1914–1918". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- Hammond, Cambrai 1917, pp. 396–402

- MCpl Mathieu Dubé (30 April 2010). "Strathconas Celebrate the Battle of Moreuil Wood". Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) Society. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- "History of a Regiment". Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) Society. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- "Charge of Flowerdew's Squadron". Canadian War Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- "Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division". University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force Academy. Archived from the original on 2015-02-28. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Falls Official History Egypt & Palestine Vol. 1 pp. 175–99, 376–77, p. 344, Vol. 2 Part I pp. 49–60, Part II pp. 547–54

- Pugsley, The Anzac Experience, p. 119

- Powles, 'The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine', p. 150

- "Walers: horses used in the First World War". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- "Attack on Beersheba". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- See also First Transjordan attack on Amman (1918)#Bridgehead established for a description of the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment's mounted attack of Ottoman cavalry.

- Mitchell, Light Horse, pp. 3–4

- "Horses: The Horse at War". Australian Stock Horse Society. Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- Wifried, Military Operations in France and Belgium 1917, p. iv

- Keegan, The First World War, p. 20

- Erickson, Ordered to Die, p. 144

- "Animals at War Captions" (PDF). Imperial War Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- Herwig, The Marne, 1914, p. 261

- Jarymowycz, Cavalry from hoof to track, pp. 137–38

- Ellis, Cavalry, pp. 177–78

- Keegan, The First World War, p. 161

- Ellis, Cavalry, p. 178

- Keegan, The First World War, p. 117

- Meyer, A World Undone, p. 321

- Erickson, Ordered to Die, pp. 5–6

- Erickson, Ordered to Die, pp. 64, 105–07

- Whitman, Edward C. (Summer 2000). "Daring the Dardanelles: British Submarines in the Sea of Marmara During World War I". Undersea Warfare. 2 (4). Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- Erickson, Ordered to Die, pp. 172–74

- Urwin, The United States Cavalry, pp. 174–76

- Urwin, The United States Cavalry, pp. 179–80

- Keegan, The First World War, p. 77

- Schafer, "Animals, Use of" in The European Powers in the First World War, p. 52

- Meyer, A World Undone, p. 531

- Schafer, "Animals, Use of" in The European Powers in the First World War, p. 53

- Hammond, Cambrai 1917, pp. 425–26

- "The Mounted Soldiers of Australia". The Australian Light Horse Association. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- "Battle of Megiddo – Palestine campaign". History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- Judson, Chemical and Biological Warfare, p. 68

- "Bert Stokes remembers Passchendaele". New Zealand History Online. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- Reakes, The War Effort of New Zealand, p. 159

- "1900: The Horse in Transition: The Horse in World War I 1914–1918". International Museum of the Horse. Archived from the original on 2010-09-26. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- Singleton, John (May 1993). "Britain's military use of horses 1914–1918". Past & Present. 139 (139): 178–204. doi:10.1093/past/139.1.178. JSTOR 651094.

- Reakes, The War Effort of New Zealand, p. 154

- Gilbert, The First World War, pp. 477–79

- Keegan, The First World War, p. 73

- Pinney, The Working Horse Manual, pp. 24–25

- Schafer, "Animals, Use of" in The European Powers in the First World War, pp. 52–53

- Gilbert, The First World War, p. 235

- Holmes, Military History, p. 417

- Keegan, A History of Warfare, p. 308

- Holmes, Tommy, p. 163

- Stout, War Surgery and Medicine, p. 479

- Carbery, The New Zealand Medical Service in the Great War 1914–1918, p. 223

- "Gas mask for horses, Germany, 1914–1918". Science Museum, London. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- "Gas Masks for Horses; Improved Device Being Made for American Army". The New York Times. June 1, 1918. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- Reakes, The War Effort of New Zealand, pp. 155–57

- Blenkinsop, History of the Great War, pp. 79–81

- Blenkinsop, History of the Great War, p. 81

- "Sandy: The only horse to return from the First World War". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- Pugsley, The Anzac Experience, p. 146

- Thorpe, Vanessa (December 10, 2011). "Spielberg's film of War Horse gives new impetus to animal charity". The Observer. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- "Animal War Heroes statue unveiled". BBC. November 24, 2004. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- Hawley, David (December 24, 2008). "Longfellow, Ole Bull in treasure trove of statues and curiosities gracing Minneapolis parks". Minnpost. Archived from the original on 2011-01-05. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- "Image: Desert Mounted Corps Memorial, Anzac Parade, Canberra, popularly known as the Light Horse Memorial". ACT Heritage Library. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- Gunn, Gail (September 1, 2003). "Burying the 1st AIF". Sabretache.

- Larkins, Damien (May 21, 2009). "War Memorial honours animals great and small". ABC News. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- "Sir Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)". The Leicester Galleries. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- "Sir Alfred Munnings – The Artist". Sir Alfred Munnings Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-09-04. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- "Artchive: Umberto Boccioni: Charge of the Lancers". artchive.com. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- "The Retreat from Mons 1914". Royal Artillery Historical Society. Archived from the original (DOC) on 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Fortunino Matania, b. 1881. "Help the Horse to Save the Soldier" : Please Join the American Red Star Animal Relief..." University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- "Stories: 'Goodbye Old Man'". Animals in War Memorial Fund. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- Fleming, L. "The War Horse". Emory University. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- "Australian Light Horse Memorial". Anzac Day Commemoration Committee. 2005. Archived from the original on 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- McClintock, Pamela (2010-10-13). "DreamWorks' holiday 'War Horse'". Variety. Los Angeles. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

References

- Braddon, Russell (1977). All the Queen's Men: The Household Cavalry and the Brigade of Guards. New York: Hippocrene Books, Inc. ISBN 0-88254-431-4.

- Blenkinsop, L.J.; J.W. Rainey, eds. (1925). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents Veterinary Services. London: H.M. Stationers. OCLC 460717714.

- Carbery, A. D. (1924). The New Zealand Medical Service in the Great War 1914–1918. New Zealand in the First World War 1914–1918. Auckland, NZ: Whitcombe and Tombs. OCLC 162639029.

- Carver, Michael (1998). Britain's Army in the 20th Century. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-73777-6.

- Dent, Anthony (1978). Cleveland Bay Horses. Canaan, NY: J.A. Allen. ISBN 0-85131-283-7.

- Ellis, John (2004). Cavalry: The History of Mounted Warfare. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books (Pen & Sword Military Classics). ISBN 1-84415-096-8.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Contributions in Military Studies, Number 201. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31516-7.

- Falls, Cyril; G. MacMunn (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from the outbreak of war with Germany to June 1917. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. 1. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 610273484.

- Falls, Cyril (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. 2 Part I. Maps by A. F. Becke. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 644354483.

- Falls, Cyril (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. 2 Part II. Maps by A. F. Becke. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 256950972.

- Gilbert, Martin (1994). The First World War: A Complete History (First American ed.). New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-1540-X.

- Hammond, Bryn (2009). Cambrai 1917: The Myth of the First Great Tank Battle. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2605-8.

- Herwig, Holger H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- Holmes, Richard, ed. (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866209-2.

- Holmes, Richard (2005). Tommy: the British soldier on the Western Front 1914–1918. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-713752-4.

- Jarymowycz, Roman Johann (2008). Cavalry from hoof to track. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98726-8.

- Judson, Karen (2003). Chemical and Biological Warfare. Open for Debate. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 0-7614-1585-8.

- Keegan, John (1994). A History of Warfare. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-73082-6.

- Keegan, John (1998). The First World War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40052-4.

- McPherson, J.W.; Carman, Barry; McPherson, John (1985). The Man Who Loved Egypt: Bimbashi McPherson. London: British Broadcasting Corp. ISBN 0-563-20437-0.

- Meyer, G. J. (2006). A World Undone: The Story of the Great War 1914 to 1918. New York: Bamtam Dell. ISBN 978-0-553-38240-2.

- Mitchell, Elyne (1982). Light Horse: The Story of Australia's Mounted Troops. Melbourne: MacMillan. ISBN 0-7251-0389-2.

- Pinney, Charlie (2000). "The Ardennes". The Working Horse Manual. Ipswich, UK: Farming Press. ISBN 0-85236-401-6.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. III. Auckland, NZ: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 2959465.

- Pugsley, Christopher (2004). The Anzac Experience: New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War. Auckland, NZ: Reed Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7900-0941-4.

- Reakes, C. J. (1923). "New Zealand Veterinary Corps". The War Effort of New Zealand. New Zealand in the First World War 1914–1918. Auckland, NZ: Whitcombe and Tombs. OCLC 220050288.

- Schafer, Elizabeth D. (1996). "Animals, Use of". In Tucker, Spencer (ed.). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8153-3351-X.

- Stout, T. Duncan M. (1954). War Surgery and Medicine. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. Wellington, NZ: Historical Publications Branch. OCLC 4373341.

- Urwin, Gregory J. W. (1983). The United States Cavalry: An Illustrated History. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1219-8.

- Wifried, Capt. (compiler) (1991). "Preface". Military Operations in France and Belgium 1917: The Battle of Cambrai. London: Imperial War Museum/The Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-162-8.

- Willmott, H. P. (2003). World War I. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-9627-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horses in World War I. |

- The Mighty Warrior – Extended story of one Canadian cavalry horse

- British Cavalry on the Western Front 1916–1918