House of Sallust

The House of Sallust (also known in earlier excavation reports as the House of Actaeon) is a domus or elite residence in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii (VI, 2, 4). The oldest parts of the house have been dated to the 4th century BCE, but the main expansions were built in the 2nd century BCE during the Roman period. The long history of this structure provides important evidence about the development of elite residences in Pompeii. The house is located on the east side of the Via Consolare. It received its modern name from an election notice placed on the facade, recommending Gaius Sallustius for office. An alternative name is the House of A. Cossus Libanus, from a seal found in the ruins. The site was later damaged by a bomb in World War II, and was restored in 1970.

Although some scholars date the excavation of this structure between 1805 and 1809 followed by the reproduction of its extensive artworks by artists until 1817, an entry dated April 29, 1775 in the Pompeianarum Antiquitatum Historia, a compilation of excavation notes, clearly indicates the house, or at least a portion containing the fresco of Actaeon, had been exposed much earlier and had already resulted in its designation as the House of Actaeon by that time. A dearth of records for 1805, 1808, and 1809 further complicates documentation of the excavation which was exacerbated by the turbulent political changes in Naples as a result of the Napoleonic Wars.[1] Since archaeologists at Pompeii were subsidized by the government, this meant funds available for excavation shifted radically with each change of authority. In January 1799, with Napoleon's troops already stationed in Naples, a rebellion led by progressive aristocrats expelled King Ferdinand and established a republic for a few months. Then this newly established but poorly funded republic was overthrown by conservative forces who reinstated the king. In 1806, right in the midst of excavations of the house, Napoleon drove away King Ferdinand and imposed his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as king until 1808, when Napoleon ordered the crown passed to his brother-in-law, Joaquim Murat. Murat’s consort, Napoleon’s younger sister, Caroline Bonaparte, invested her own funds into excavations, engaging six hundred workmen to continue the task. But, In June 1815, King Ferdinand returned again, now as King of the Two Sicilies, and sent Murat before a firing squad in September of that year. The archaeologists' funding dwindled drastically as the restored monarch cut the number of excavators at work in Pompeii from three hundred to a mere thirteen.[2]

History

_(14595762297).jpg.webp)

The House of Sallust was among some of the most sumptuous dwellings found in Regio VI in the northwest part of Pompeii and was among the first to be uncovered and plundered during the explorations of the 18th century. The earliest work on the House of Sallust was directed by Francesco La Vega and then his brother Pietro who clearly demonstrated how archaeology during this early period was performed at the bequest and for the benefit of the aristocracy. Queen Maria Caroline of Bourbon, a sponsor and spectator of the excavations of the house, received particularly artistic finds as gifts and work would cease in a room once the finds were stripped. When the house was considered fully cleared in 1809, work turned to reproducing the remains and surviving frescoes with paintings and drawings.

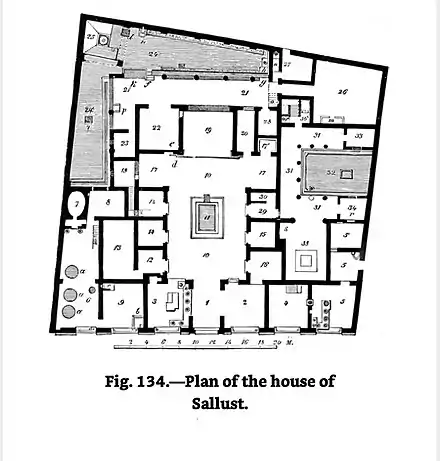

The house was originally a single symmetrical atrium house decorated in the Pompeian First Style[3] from the Samnite Period, and was made of tufa blocks. The axially-aligned structure featured a central fauces, set between frontage shops, that lead to an atrium with compluvium and impluvium, three cubicula and alae that flanked the atrium on each side. A tablinum was placed at the rear of the atrium with an oecus and andron on the left and right side of the tablinum respectively. Behind the tablinum was an outdoor garden enclosed by the property wall.[4]

In successive building phases, additional shops were added on its west side and a peristyle (colonnaded porticus) was added to the garden.[5]

In the late Augustan period the house was converted into a hospitium, a hotel on a grand scale. A counter accessible both from the street and the atrium was constructed to encourage potential guests passing by as well as service existing visitors. Rooms were grouped into suites around the atrium and larger spaces 22 and 35 off the northeast corner of the atrium (see plan) provided indoor dining spaces while an outdoor masonry triclinium (25) covered by a pergola supported by two pilasters at the north end of the peristyle garden provided outdoor dining space. A hearth was constructed nearby for hot food preparation.

A large window was installed in the tablinum (19) to provide guests with a view of the garden enhanced by the tablinum's elevation of three steps above the atrium floor. The tablinum was modified to allow access from either end of the colonnade and, although a relatively small 20 by 70 foot space, was painted on the back wall with a garden scene which served as a continuation of the real garden, incorporating garlanded columns, three fountains, and birds.

Even with the addition of these new features, such as the peristyle garden which was imported from Greece in the 2nd century BCE, and the second atrium, which also became popular around this time, archaeologists point out that great care was exercised in the remodeling to preserve the original Samnite aesthetic characteristics.[3] Its First Style decoration was retained in some of its public spaces over time, too, imitating the continued use of the First Style in Pompeii's temples, basilicas, and gymnasia into the imperial period.[6]

Retention of the old may have been used intentionally to generate creative contrasts. Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill points out the First Style marble incrustation decoration of the House of Sallust's spacious atrium was carefully preserved over as long as two centuries while the adjoining peristyle was richly and charmingly decorated in the "modern" style of the imperial period. The House of Sallust is not unique in Pompeii in its use of decorative contrasts.[6]

The structure was eventually expanded to use almost all the garden space, but its development was cut short due to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

List of numbered rooms according to 1817 original floor plan

- 1. Principal entrance

- 2. Vestibulum

- 3. A shop with a counter and jars, probably for wine or oil

- 4. Apartment connected with a doorway to apartment 5.

- 5. Apartment connected with a doorway to Apartment 4.[7] Grouping rooms into suites not only provided more spacious accommodation but allowed guests to pass in astonishment from one fine room to another elevating the perception of wealth of the master of the house.[6]

- 6. Compluvium for collecting rain water from the room. The bronze sculpture of Hercules and the Golden Hind was found here.

- 7. Altar with niche for the household gods

- 8. Tablinum with an adjoining room (9) with views of the porticus and garden. The inner room was probably a small triclinium or cubiculum and was adorned with representations of scenic masks.[7] The space was originally accessed directly from the atrium but this doorway was blocked after the rear wall was replaced with a wide entrance to the porticus overlooking the viridarium.[8]

- 10. Cella familliaria or bed chamber less than 10 foot square.[7]

- 11. Alae - side recesses containing the sacred ancestral images.[9] The ala on the left has a doorway to the adjoining room 12 that has a doorway to the colonnaded ambulatory (20) leading to the viridarium (19). A stairway was installed in (12) at a later time to access a new upper floor. The ala on the right has a doorway to an adjoining lararium or pinacotheca (picture gallery) (13).[7] Later archaeologists identify room (13) as a wardrobe.[8]

- 14. Andron with opening to the columned porticus fronting the viridarium. The porticus was three feet above the viridarium (19), accessed by two flights of steps. In between the blue-accented columns of the porticus (15) and (16) were dwarf walls (plutei) forming a container for soil and plants watered by a gutter that collected rainwater from the roof. The back wall of the viridarium was painted with plants and birds to extend the garden view. On the right side of the viridarium was a cistern (17). On the left side of the viridarium was a covered triclinium (18) with pedestal for a table.[7] A small altar was positioned in front of the triclinium on the left. Only the edges of this portion of the garden, which is higher than the floor of the colonnade, were planted.[8]

- 19. Fountain

- 20. A roofed cistern

- 21. Cubiculum

- 22. A commode (latrine)

- 23. Back entrance

- 24. Passageway to a courtyard and perhaps access to the kitchen (26)

- 25. Places for ashes or hearths for food preparation

- 26 Kitchen with a latrine for the women's apartments on the left and, up a few steps, an elevated hearth on the right. To the left of the hearth is a three-foot deep arched recess (lararium?)

- 27. Entrance to a third court (31) with cell for a porter.

- 28. Altar with painting of Diana bathing and Actaeon with horns transforming into a stag, attacked by his own hounds, on the back wall of the gynaeceum.

- 29. Small apartments or cubicula on the left and right back side of the gynaeceum. The cubiculum on the right with floor pavement and socle of different colored marbles featured a delicate painting of Mars and Venus with Cupid playing with Mars' shield[7] and a scene of Paris and Helen on its rear inner wall, and had a recess for Penates or Lares. Its outer wall was painted with a scene of Phrixus and Helle with the ram. The outer wall of the cubiculum on the left was painted with a scene of Europa with the bull.[8]

- 30. Large dining room.

- 31. Third courtyard, perhaps the gynaeceum or women's apartments, with porticus lined with octangular columns painted red. At first the colonnade had a flat roof, with an open walk above on the three sides, but when the large dining room (30) was constructed, the flat roof and promenade on that side were replaced by a sloping roof over the broad entrance to the dining room.[8]

The atrium (cavaedium) featured opus signinum floor pavement with painted Ionic columns supporting the roof giving the space a monumental appearance. Its walls were painted to emulate slabs of marble typical of the First Style.[7] The treatment of the entrances to the tablinum and the alae, with pilasters joined by projecting entablatures, the severe and simple decoration, and the admission of light through the compluvium increased the apparent height of the room and gave it an aspect of dignity and reserve.[8]

_(14595765227).jpg.webp)

Although emphasis on the vista from the front door to the tablinum on to the garden began to diminish in other atrium houses in the 1st century CE, this was not the case here.[6] The Republican atrium-tablinum-peristyle matrix remained in place in the House of Sallust despite its conversion to a primarily public establishment, so patronus-client relationships may have persisted for its owner into the early Empire. The arrangement also facilitated the enticement of potential guests from the busy traffic on the Via Consolare. The expansions of the house to encompass more entertainment spaces, however, did emulate such proliferation by other wealthy residents during this period.[6]

A scene of sacrifice greeted visitors on a false door to the left of the tablinum. A priest, with his head covered, pours the contents of a patera into a tripod. Opposite the priest, a young man plays a double flute, his foot upon a scabellum, a percussion instrument played by the foot in dramatic performances. On the left and right, two assistants dressed in white tunics with narrow red stripes pour a liquid from drinking horns into paterae.[7]

The southeast quadrant of the house was obliterated in an Allied bombing raid in 1943, destroying the signature fresco of Actaeon and Diana. Only a small part of the atrium's once sumptuous decoration, that included dentil cornices and fluted pilasters that framed the alae and tablinum, survived.[9]

Examinations between 1817 and 1902, (See 1902 floor plan above) attributed additional rooms to the lower right corner of the house including a caupona, a Roman tavern equipped with dolia to serve hot food. The caupona had a rear doorway leading to two interconnected rooms, one with an external entrance probably for food deliveries, all labeled (5) on the 1902 plan.[8]

In the lower left corner of the structure, later archaeologists identified a bakery complex with a millroom with three mills, labeled (6) on the 1902 plan, with a stairway to an upper floor, an oven (7), a kneading room (8), and a kitchen (9). They also identified the enclosure of part of the upper left colonnade to form a room labeled (23) on the 1902 plan.

Gallery

Watercolor of Women's apartments in the House of Sallust by Luigi Bazzani

Watercolor of Women's apartments in the House of Sallust by Luigi Bazzani_of_the_House_of_Sallust_(VI_2%252C_4)_in_Pompei_watercolor_by_Luigi_Bazzani.jpg.webp) Watercolor of The Genaeceum of the House of Sallust (VI 2, 4) by Luigi Bazzani

Watercolor of The Genaeceum of the House of Sallust (VI 2, 4) by Luigi Bazzani Hercules capturing the Golden Hind of Artemis found in the atrium.

Hercules capturing the Golden Hind of Artemis found in the atrium. A drawing of a venereum in the House of Sallust

A drawing of a venereum in the House of Sallust Triclinium at the south end of the viridarium with blue-accented columns

Triclinium at the south end of the viridarium with blue-accented columns_(14595632648).jpg.webp) Panel painting of theater masks in the tablinum. The cup and hellebore clearly identify the masks as tragic. The surrounding ornaments, painted red and blue upon grounds of pink and white, were copied from various parts of the house.[7]

Panel painting of theater masks in the tablinum. The cup and hellebore clearly identify the masks as tragic. The surrounding ornaments, painted red and blue upon grounds of pink and white, were copied from various parts of the house.[7]_(14595765927).jpg.webp) Viridarium with triclinium

Viridarium with triclinium Atrium as of 2012

Atrium as of 2012 First style imitation marble panels in the atrium

First style imitation marble panels in the atrium_(14595560090).jpg.webp) Engraving of the Atrium as of 1817

Engraving of the Atrium as of 1817

See also

Notes

- Fiorelli, Giuseppe (25 March 2019). Pompeianarum Antiquitatum Historia. New York, NY: Wentworth Press. ISBN 978-1011180820.

- Rowland, Ingrid D. (2014). From Pompeii, The Afterlife of a Roman Town. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04793-8.

- Dobbins, John J.; Foss, Pedar W. (2007). The World of Pompeii. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47577-8.

- Dicus, K. (2017). "Review of Bringing to light the chequered story of the House of Sallust in Pompeii (VI,2,4) by Anne Laidlaw and Marco Salvatore Stella". Journal of Roman Archaeology. Supplementary Series no. 98 (30): 610–614. doi:10.1017/S1047759400074419.

- "Pompeii and the domestic garden".

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (1994). Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02909-2.

- Gell, Sir William; Gandy, John P. (1817–1819). Pompeiana : the topography, edifices, and ornaments of Pompeii. London, England: Rodwell and Martin.

- Mau, August (1902). Pompeii, It's Life and Art. New York: The MacMillan Company.

- Guzo, Pier Giovanni; d'Ambrosio, Antonio (2002). Pompeii: Guide to the Site. Italy: Ministero per i Beni e le Attivita Culturali. ISBN 88-510-0020-4.