Hurricane Humberto (2007)

Hurricane Humberto was a Category 1 hurricane that formed and intensified faster than any other North Atlantic tropical cyclone on record, before landfall. The ninth named storm and third hurricane of the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season, Humberto developed on September 12, 2007, in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico,. The tropical cyclone rapidly strengthened and struck High Island, Texas, with winds of about 90 mph (150 km/h) early on September 13. It steadily weakened after moving ashore, and on September 14, Humberto began dissipating over northwestern Georgia as it interacted with an approaching cold front.

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

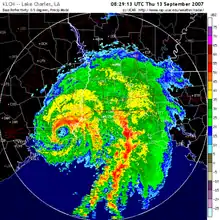

Hurricane Humberto at peak intensity while making landfall in Texas, early on September 13 | |

| Formed | September 12, 2007 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 14, 2007 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 90 mph (150 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 985 mbar (hPa); 29.09 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 indirect |

| Damage | $50 million (2007 USD) |

| Areas affected | Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, The Carolinas |

| Part of the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Damage was fairly light, estimated at approximately $50 million (2007 USD). Precipitation peaked at 14.13 inches (358.9 mm), while wind gusts to 85 mph (137 km/h) were reported. The heavy rainfall caused widespread flooding, which damaged or destroyed dozens of homes, and closed several highways. Trees and power lines were downed, knocking out power to hundreds of thousands of customers. The hurricane caused one fatality in the State of Texas. Additionally, as the storm progressed inland, rainfall was reported throughout the Southeast United States.

Meteorological history

The origins of Humberto can be traced to the remnants of a frontal trough—the same one that spawned Tropical Storm Gabrielle—that moved offshore of south Florida on September 5.[1][2] The combination of a weak surface trough and an upper-level low pressure system produced disorganized showers and thunderstorms from western Cuba into the eastern Gulf of Mexico.[3] Tracking slowly west-northwestward, unfavorable wind shear initially inhibited tropical cyclone development.[4] By late on September 11, environmental conditions became more favorable,[5] and the following morning convection increased over the disturbance.[6] Tracking around the western periphery of a mid-level ridge, the system turned on a slow northwest drift and quickly organized. Radar imagery reported loose banding features, and buoy data indicated the presence of a surface circulation; based on the observations, the National Hurricane Center classified the system as Tropical Depression Nine, while located roughly 60 miles (100 km) southeast of Matagorda, Texas.[7]

Upon becoming a tropical cyclone, the tropical depression was forecast to strengthen slowly to reach peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[7] Within three hours of forming, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Humberto.[8] A small cyclone, the storm continued to organize quickly as it turned north-northeastward, while radar imagery suggested the formation of an eye by early on September 13.[9] Based on reports from Hurricane Hunters, Humberto was upgraded to a hurricane at 0515 UTC on September 13, while located about 15 miles (20 km) off the coast of Texas.[10] The hurricane made landfall a few miles to the east of High Island at around 0700 UTC. A well-defined eye was maintained with strong convection around it, and Hurricane Hunters reported sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) about two hours after landfall.[11] However, post-storm analysis later determined that the winds were a bit stronger—about 90 mph (150 km/h).[2]

Based on operational estimates of a wind speed increase of 50 mph (85 km/h), the National Hurricane Center reported that "no tropical cyclone in the historic record has ever reached this intensity at a faster rate near landfall." The path of the eye continued northeastward and passed over Port Arthur, Nederland, Port Neches, Groves, and Bridge City, Texas at Category 1 hurricane strength. This was the second time within two years (following Hurricane Rita on September 24, 2005) that these cities experienced a direct hit from a hurricane. By eight hours after landfall, Humberto weakened to a tropical storm as it crossed into southwestern Louisiana.[12] Increased upper-level wind shear caused the storm to weaken rapidly over land, and late on September 13 Humberto weakened to a tropical depression. Upon issuing its last advisory, the National Hurricane Center remarked on the potential for the remnants of the storm to turn southward into the Gulf of Mexico.[13] However, the storm continued northeastward through the southeastern United States, and on September 14, the storm began dissipating over northwestern Georgia, and shortly thereafter degenerated into a remnant low pressure area.[14]

Preparations

Upon becoming a tropical cyclone, a tropical storm warning was issued from Port O'Connor, Texas, to Cameron, Louisiana, and a tropical storm watch was posted from Cameron to Intracoastal City, Louisiana;[15] after Humberto became a tropical storm, the watch was upgraded to a warning.[16] Upon reaching hurricane status, the National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane warning from High Island, Texas, to Cameron, Louisiana.[17] An inland tropical storm warning was declared for several parishes in southwestern Louisiana.[18] The National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center posted a tornado watch for southwestern coastal parishes.[12]

Prior to moving ashore, officials in Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana, advised residents in low-lying or flood-prone areas to consider moving to a safer location. A shelter was opened in Lake Charles,[18] where 29 people stayed during the storm.[19] Flood watches and warnings were issued for portions of Mississippi and Louisiana as the storm tracked across the region.[20] Texas Governor Rick Perry, prepared state resources for the potentially impacted areas, including the deployment of 200 Texas Military Forces soldiers and six Black Hawk helicopters and two water rescue teams for search and rescue missions. The Texas State Operations Center was activated shortly after the cyclone developed.[21]

Impact

Texas

A few hours prior to its development, outer rainbands from the depression began moving over portions of the Texas coast.[6] Heavy rainfall from intense thunderstorms caused minor flooding as they crossed the coastline during the subsequent days;[22] precipitation in the state peaked at 14.13 inches (358.9 mm) at East Bay Bayou, the highest recorded rainfall total in association with the hurricane.[14] Sustained winds peaked at 69 mph (112 km/h) with gusts to 85 mph (137 km/h) at Sea Rim State Park; the National Weather Service estimates gusts exceeded 90 mph (145 km/h) in southwestern Jefferson County and extreme southeastern Chambers County.[23] In the Golden Pass Ship Channel, an unofficial report of a 115 mph (185 km/h) wind gust was relayed to the National Hurricane Center.[2] Upon moving ashore, Humberto produced a minor storm surge in the state, peaking at 2.86 feet (0.87 m) at Rollover Pass; the combination of surge and waves resulted in light beach erosion.[22]

Hurricane Humberto left 10 homes completely destroyed in Galveston County, with an additional 19 severely damaged in the county; several homes received minor shingle damage, and road closures left about 5,000 houses isolated in the county. The combination of saturated grounds and strong winds uprooted many trees and downed power lines across the path of the hurricane,[22] with at least 50 high voltage transmission poles blown down or seriously damaged; over 120,000 power customers in Orange and Jefferson counties lost power,[19] with 118,000 Entergy customers in the state without electricity.[24] Widespread flooding occurred in Jefferson and Orange counties, and at least 20 homes in Beaumont were flooded. Additionally, several roadways were flooded. The passage of the hurricane caused one fatality in the state; a Bridge City man was killed when his carport crashed on him outside his house.[19] Initially, press reports indicated that the storm wrought up to $500 million in damage;[25] however, final damage estimates were about $50 million.[2]

Oil production was slowed as a result of Humberto, as at least four refineries—the Valero, ExxonMobil, Total SA and Motiva Enterprises LLC plants in Port Arthur—were halted due to the loss of power. Oil prices rose above $80 a barrel in intraday trading on September 12 as a result, ending the next day at a record high of $80.09 a barrel.[26][27] Natural gas futures rose 8 percent ahead of the storm, but lost most of those gains the next day.[27]

According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), 1,464 residences throughout Texas were affected by Hurricane Humberto. Of these, 25 were destroyed, 96 sustained major damage and 240 sustained minor damage. The cost of individual assistance for those impacted by Humberto would cost $4,776,334; the cost of debris removal and other public assistance amounted to $6,682,074. In terms of per capita income, Jefferson County sustained the most impact, decreasing by $22.38.[28]

Louisiana

Tracking through the state as a weakening tropical storm, Humberto produced light to moderate winds across southwestern Louisiana. Gusts officially peaked at 43 mph (69 km/h) in the state, although an unofficial reading of 55 mph (89 km/h) was reported in Vinton.[23] Heavy rainfall occurred across the area, reaching a peak of 8.25 inches (210 mm) in DeRidder.[29] The rainfall triggered minor river flooding along the Vermilion River in Lafayette. Storm surge was minor in the state, peaking at 2.13 feet (0.65 m) in Cypremont Point;[2] no beach erosion was reported.[19]

Widespread freshwater flooding occurred in Beauregard Parish, leaving homes in DeRidder flooded. High water across the southwestern portion of the state resulted in the closure of several roadways, including U.S. Route 171 and various state highways. Isolated wind damage was reported, particularly near the Texas border, with some trees and power lines blown down. A total of about 13,000 power customers lost electricity in southwestern Louisiana.[19] One F1 tornado briefly touched down in Vermilion Parish, blowing the roof off one home and downing trees and power lines.[30] Damage throughout Louisiana was estimated at $525,000.[31]

Southeast United States

After the circulation dissipated, the remnants of Humberto brought moderate rainfall to the southeastern states and spawned several tornadoes across portions of South Carolina and North Carolina and caused widespread damage in some locations.[32] Heavy rains in Mississippi led to flooding in low-lying areas. In Hinds County, a small rail bridge was washed out, forcing all Amtrak train passengers to take a bus to their destinations.[33] One person was injured after driving his car into a flooded street.[34] In Alabama, rainfall up to 5.06 in (129 mm) caused minor ponding in low-lying areas but aided in short-term drought relief.[35] In northern Georgia, locally heavy rainfall led to flash flooding, resulting in several road closures.[36] Strong thunderstorms associated with the remnants of Humberto also produced winds up to 51 mph (82 km/h) and penny-sized hail.[37] Throughout North Carolina, ten F0 tornadoes were confirmed,[31] resulting in minor damage to homes, though none caused injuries or fatalities.[38] Heavy rains associated with the system also triggered flash flooding along some roads, resulting in their closure.[39] In South Carolina, one F1 tornado touched down in Laurens County, causing moderate damage to several homes before lifting.[40]

Aftermath

Hours after Humberto made landfall, Rick Perry declared Galveston, Jefferson, and Orange counties as disaster areas, which allocated state resources to assist the affected residents.[21] The governor applied for a presidential disaster declaration on September 21.[41] Four Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) teams assessed the hurricane damage in the three most affected counties.[42] Following their assessment, they determined that the damage caused by Humberto was not significant enough to require a disaster declaration. As such, Governor Rick Perry's request from FEMA was denied.[43] Across the Bolivar Peninsula, an estimated 1,500 cubic yards of structural debris and 3,000 cubic yards of tree limbs were needed to be removed in the wake of the storm.[44]

See also

References

- "WMO RA IV Hurricane Committee Final Report" (PDF). World Meteorological Organization. April 28, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- Eric S. Blake (November 28, 2007). "Hurricane Humberto Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- Jack Beven (September 8, 2007). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Jamie Rhome (September 10, 2007). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Richard Pasch; Chris Landsea (September 11, 2007). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Michelle Mainelli (September 12, 2007). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- James Franklin (September 12, 2007). "Tropical Depression Nine Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- James Franklin (September 12, 2007). "Tropical Storm Humberto Public Advisory One-A". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Richard Pasch (September 12, 2007). "Tropical Storm Humberto Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Michelle Mainelli; Lixion Avila (September 13, 2007). "Hurricane Humberto Special Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Michelle Mainelli; Lixion Avila (September 13, 2007). "Hurricane Humberto Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- James Franklin (September 13, 2007). "Tropical Storm Humberto Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Jack Beven (September 13, 2007). "Tropical Depression Humberto Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Christopher Hedge (September 14, 2007). "Public Advisory 11 for the Remnants of Humberto". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- James Franklin (September 12, 2007). "Tropical Depression Nine Public Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- James Franklin (September 12, 2007). "Tropical Storm Humberto Public Advisory Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Michelle Mainelli; Lixion Avila (September 13, 2007). "Hurricane Humberto Public Advisory Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Roger Erickson (September 13, 2007). "Hurricane Humberto Local Area Statement". Lake Charles National Weather Service. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Landreneau, Shamburger, Erickson, and Rua (2007). "Hurricane Humberto Post-Tropical Cyclone Report". Lake Charles, Louisiana National Weather Service. Retrieved September 20, 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Daniel Petersen (September 13, 2007). "Public Advisory 9 for the Tropical Depression Humberto". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- Office of the Governor of Texas (2007). "Texas Governor Perry Declares Three Texas Counties Disaster Areas". Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Blood, Overpeck, Lichter (2007). "Hurricane Humberto Post-Tropical Cyclone Report". Houston, Texas National Weather Service. Retrieved September 19, 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- National Weather Service (2007). "Hurricane Humberto Winds & Lowest Pressures". Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Dan Wallach (September 17, 2007). "11:00 a.m.: Entergy determining costs of Humberto". Beaumont Enterprise. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Associated Press (September 14, 2007). "Power being restored in Texas, Louisiana". NBC News. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- Robinson, Matthew (September 13, 2007). "Oil hits record over $80". Reuters.

- Saefong, Myra P. (September 13, 2007). "Oil futures mark first-ever close above $80 a barrel". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 15, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- "Texas Hurricane Humberto – Denial" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. October 16, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- David M. Roth (2008). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- "Louisiana Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "NCDC Storm Events Database". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Raleigh, North Carolina National Weather Service (September 14, 2007). "Hurricane Humberto Special Weather Statement". Archived from the original on January 24, 2010. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- "Mississippi Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Mississippi Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Alabama Event Report: Heavy Rain". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Georgia Event Report: Heavy Rain". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Georgia Event Report: Hail". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- WRAL5.com (September 14, 2007). "Humberto's Ghost Lashes Triangle With Winds and Rain". Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- "North Carolina Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "South Carolina Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Sarah More (2007). "Much-watched storm remains nameless as it drifts onto land". Beaumont Enterprise. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- Harvey Rice (September 19, 2007). "Gov. Perry may request federal aid for Humberto victims: Teams expected to complete survey today or Thursday". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- Christine Rappleye (October 20, 2007). "FEMA: Humberto was not a disaster". The Enterprise. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Associated Press (September 15, 2007). "Cleanup begins after Hurricane Humberto". USA Today. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Humberto (2007). |