Hurricane Paul (1982)

Hurricane Paul was a particularly deadly and destructive Pacific hurricane which killed a total of 1,625 people and caused $520 million in damage. The sixteenth named storm and tenth hurricane of the 1982 Pacific hurricane season, Paul developed as a tropical depression just offshore Central America on September 18. The depression briefly moved inland two days later just before heading westward out to sea. The storm changed little in strength for several days until September 25, when it slowly intensified into a tropical storm. Two days later, Paul attained hurricane status, and further strengthened to Category 2 intensity after turning northward. The hurricane then accelerated toward the northeast, reaching peak winds of 110 mph (175 km/h). Paul made landfall over Baja California Sur on September 29, and subsequently moved ashore in Sinaloa the next day.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

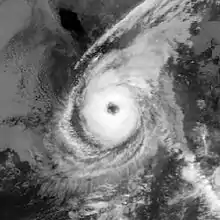

Hurricane Paul at peak intensity prior to landfall on the Baja Peninsula on September 28 | |

| Formed | September 18, 1982 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 30, 1982 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 110 mph (175 km/h) |

| Fatalities | 1,625 total, 668 missing |

| Damage | $520 million (USD) |

| Areas affected | Guatemala, El Salvador, Baja California, Northwest Mexico, United States |

| Part of the 1982 Pacific hurricane season | |

Prior to making landfall near the El Salvador–Guatemala border as a tropical depression, the precursor disturbance dropped heavy rainfall over the region, which later continued after landfall. Many rivers in the region burst their banks after five days of rainfall, causing severe flooding and multiple mudslides. Throughout Central America, at least 1,363 people were killed, with most of the fatalities occurring in El Salvador, although some occurred in Guatemala. Another 225 deaths were attributed to floods from the depression in southern Mexico. In addition, Paul was responsible for 24 fatalities and moderate damage in northwestern Mexico, where it made landfall at hurricane strength.

Meteorological history

The precursor disturbance to Paul originated from an area of low barometric pressure and disorganized thunderstorms, which was first noted near the Pacific coast of Nicaragua on September 15. Several days later, satellite imagery indicated it had developed a center of cyclonic circulation; on 1800 UTC September 20, the Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center initiated advisories on the system and classified it as Tropical Depression Twenty-Two. At that time, it was located 200 mi (320 km) west of Managua, Nicaragua and supported winds of 35 mph (50 km/h). The depression turned northward in response to a weak steering flow between two high pressure systems—one near Cabo San Lucas and the other west of Central America. It then moved inland near the El Salvador–Guatemala border, and dissipated overland.[1]

Under the influence of a persistent stationary trough near California, the remains of the depression retraced westward back over the open waters of the Pacific. Advisories on the system were resumed late on September 20. Though it was reconsidered a tropical cyclone, its wind circulation was poorly defined; the depression again degenerated into an open trough at 0000 UTC September 22. Its forward motion remained relatively unchanged for several days, and by September 24 the system was reclassified as a tropical cyclone. After briefly drifting northward, the system began tracking toward the west-northwest. It gradually organized into a tropical storm at 0000 UTC September 25. Since it was then situated over favorable sea surface temperatures between 28 °C (82 °F) and 29 °C (84 °F), Paul underwent a phase of rapid intensification. This allowed it to reach Category 1 hurricane strength on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS) just two days after its naming.[1]

Upon becoming a hurricane, Paul turned to the north and continued to develop.[1] As the storm neared Baja California Sur, it reached Category 2 intensity.[2] An upper-level trough forced the hurricane to accelerate towards the northeast, at which point it had reached peak wind speeds of 110 mph (180 km/h). From 1800 to 2100 UTC on September 29, the eye of the hurricane made landfall along Baja California Sur, moving ashore less than 100 mi (160 km) south of La Paz near San José del Cabo. After weakening slightly inland, Paul briefly reemerged over water and subsequently made its final landfall near Los Mochis, Sinaloa with winds of 100 mph (165 km/h).[1] Tropical cyclone advisories were discontinued shortly thereafter,[2] though exact information on the storm after it moved inland is unavailable due to a lack of data completion in the hurricane database.[3]

Preparations

An alert was issued for the Mexican states of Sonora and Sinaloa and Baja California Sur; army and navy units were on standby in case of an emergency.[4] Roughly 50,000 people evacuated to storm shelters[5] and thousands of others sought refuge in public buildings, such as schools and churches.[6] Across La Paz, officials evacuated 3,000 families from hurricane-prone areas.[7] In the towns of Altata and Guamúchil alone, army officials evacuated 5,000 coastal residents.[8]

Impact

El Salvador

| Hurricane | Season | Fatalities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Mexico" | 1959 | 1,800 | [9] |

| Paul | 1982 | 1,625 | [10][11][12][13] |

| Liza | 1976 | 1,263 | [14][15][16] |

| Tara | 1961 | 436 | [17] |

| Aletta | 1982 | 308 | [18][19] |

| Pauline | 1997 | 230–400 | [20] |

| Agatha | 2010 | 190 | [21][22] |

| Manuel | 2013 | 169 | [23] |

| Tico | 1983 | 141 | [24][25] |

| Ismael | 1995 | 116 | [26] |

| "Baja California" | 1931 | 110 | [27][28] |

| "Mazatlán" | 1943 | 100 | [29] |

| Lidia | 1981 | 100 | [22] |

The tropical depression that later became Paul produced the worst natural disaster in El Salvador history since 1965.[1] Although the death toll was initially believed to be lower[1][30][31] it rose to a final toll of 761 after new victims were confirmed on September 28.[32] Of these deaths, 312 occurred in the capital city of San Salvador,[30] which had also sustained the worst damage.[33] Another 40 people perished in Actoo, a very small village located 42 mi (68 km) west of San Salvador.[30] Rescue workers searched through rocks and mud to find missing victims.[34] About 25,000–30,000 people were left homeless.[1] Much of San Salvador was submerged by flood waters of up to 8 ft (2.4 m) high, and even after their recession hundreds of homes remained buried under trees, debris, and 10 ft (3.0 m) of mud.[1][30] In all, property damage from the storm amounted to $100 million in the country;[30] while crop damage amounted to $250 million.[31]

Guatemala, and southern Mexico

| Storm | Season | Damage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuel | 2013 | $4.2 billion | [35] |

| Iniki | 1992 | $3.1 billion | [36] |

| Odile | 2014 | $1.25 billion | [37] |

| Agatha | 2010 | $1.1 billion | [38] |

| Willa | 2018 | $825 million | [39][40][41][42] |

| Madeline | 1998 | $750 million | [43] |

| Rosa | 1994 | $700 million | [44] |

| Paul | 1982 | $520 million | [45][31][30] |

| Octave | 1983 | $512.5 million | [46][47] |

| Norman | 1978 | $500 million | [48] |

In Guatemala, widespread catastrophic floods claimed 615 lives and left 668 others missing. More than 10,000 people were left homeless in the wake of the disaster.[49] According to the highway department, the storm destroyed 16 bridges which left 200 communities isolated from surrounding areas.[50] Overall, economic losses of $100 million (1982 USD) were reported in the country.[45] Throughout southern Mexico, floods from the precursor depression to Paul killed another 225 people.[51]

Baja California Sur

Hurricane Paul produced heavy rainfall along its path through Baja California Sur. At least 85 homes in La Paz sustained damage, and many telephone lines in the region were down at the height of the storm.[7] Wind gusts estimated at 120 mph (195 km/h) swept through San José del Cabo, causing property damage and subsequently leaving 9,000 homeless.[1] Despite the damage, no deaths were reported in the wake of Paul.[52]

Northwest Mexico and southwest United States

Upon making its final landfall in Sinaloa, Paul produced hurricane-force winds recorded at 100 mph (160 km/h) in Los Mochis. The winds demolished numerous homes in the region, leaving 140,000 residents homeless and another 400,000 people isolated.[53] The greatest damage occurred 70 miles (110 km) south of Los Mochis in the city of Guamuchil;[1] some houses suffered total destruction, while many other had their roof blown off. A total of 24 people were killed by the storm, although it produced beneficial rains over the region.[13]

The worst flooding occurred near the Rio Sinaloa; 7.9 in (200 mm) to 12 in (300 mm) of rain fell in some locations. Over 25,000 homes were damaged.[54] Agricultural damage was severe in the state of Sinaloa, with up to 40 percent of the soybean crop destroyed. Sugar cane, tomato, and rice crops also sustained damage from the hurricane, and in its wake the state's corn production was down by 26 percent from the previous year. Total storm damage in Mexico amounted to $4.5 billion (1982 MXN; $70 million USD).[1]

The remnants of Paul moved into the United States, producing heavy rainfall in southern New Mexico and extreme West Texas. Inclement weather was observed as far inland as the Great Plains.[55] A combination of rain and snow moved into Colorado; 6 in (150 mm) of snow was expected in Wyoming, thus winter storm warnings were required for parts of the state.[56]

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the storm, the Government of El Salvador was criticized for failing to keep the public well informed. It provided over $300,000 in aid and declared a state of emergency;[30][34] additionally, a state of mourning was declared.[57] The United Nations World Food program began distributing food set aside for victims of the El Salvador Civil War.[58] The U.S. Embassy in Guatemala provided $25,000 in aid for the country.[59] Mexican authorities rushed to supply food and water to the homeless.[60]

See also

- Other storms with the same name

- List of Category 2 Pacific hurricanes

- 1959 Mexico hurricane – deadliest pacific hurricane on record, only ahead of Hurricane Paul.

References

- Gunther, Emil B.; R.L. Cross; R. A. Wagoner (May 1983). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1982". Monthly Weather Review. 111 (5): 1080–1102. Bibcode:1983MWRv..111.1080G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<1080:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved 1 October 2020. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Hurricane Paul lashes Mexico". The Day. September 29, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Five die, 50,000 evacuate as hurricane hits Mexico". Eugene Register-Guard. September 30, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Hurricane Hits Mexico; 5 Dead". L.A. Times. September 30, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Hurricane Hit Southern Coast of Mexico". Reading Eagle. September 29, 1982. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "Hurricane claims 5 in Mexican sweep". Times Daily. September 30, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Natural Hazards of North America. Supplement to National Geographic magazine (Map). National Geographic Society. April 1998.

- "More Flood Victims found". The Spokesman-Review. September 28, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "More flood victims found". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. September 28, 1982. p. 12. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- "Mexico - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2008. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- "24 killed from hurricane". The Hour. October 1, 1982. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "Mexico gives up to try and find storm victims". Bangor Daily News. United Press International. October 6, 1976. p. 8. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- "Hurricane Liza rips Mexico". Beaver County Times. United Press International. October 2, 1976. p. 18. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "Historias y Anecdotas de Yavaros". Ecos del mayo (in Spanish). June 14, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (August 1993). "Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide 1900-present" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- "Nicaragua seeks aid as flood victims kill 108". The Montreal Gazette. May 28, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Canada Aids Victims". The Leader-Post. June 10, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- Miles B. Lawrence (1997). "Hurricane Pauline Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- Jack L. Beven (January 10, 2011). "Tropical Storm Agatha Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database". Université catholique de Louvain.

- Steve Jakubowski; Adityam Krovvidi; Adam Podlaha; Steve Bowen. "September 2013 Global Catasrophe Recap" (PDF). Impact Forecasting. AON Benefield. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, U.S. Agency for International Development (1989). "Disaster History: Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900-Present". Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Oklahoma residents clean up in Hurricane's wake". The Evening independent. October 22, 1983. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- Centro Nacional de Prevención de Desastres (2006). "Impacto Socioeconómico de los Ciclones Tropicales 2005" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- Associated Press (1931-11-17). "Hurricane Toll Reaches 100 in Mexico Blow". The Evening Independent. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- "World News". The Virgin Islands Daily News. 1931-09-18. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- Howard C. Sumner (1944-01-04). "1943 Monthly Weather Review" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- "El Salvador Death Toll hits 565 as more bodies found". September 22, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "5 day toll in El Salvador, 630 killed, crops, destroyed". Anchorage Daily Times. September 23, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "More Flood Victims found". The Spokesman-Review. September 28, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Salvador Flood total 565". The Courier. September 23, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Death toll expected to hit 500 in Salvador flood disaster". The Deseret News. September 21, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Jakubowski, Steve; Krovvidi, Adityam; Podlaha, Adam; Bowen, Steve. "September 2013 Global Catasrophe Recap" (PDF). Impact Forecasting. AON Benefield. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables update (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. January 12, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- Albarrán, Elizabeth (December 10, 2014). "Aseguradores pagaron 16,600 mdp por daños del huracán Odile" [Insurers paid 16,600 MDP for Hurricane Odile damages]. El Economista (in Spanish). Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Beven, Jack (January 10, 2011). "Tropical Storm Agatha Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- "Hay daños evidentes en Lerdo por lluvias" [There is obvious damage in Lerdo due to rain]. El Siglo de Durango (in Spanish). November 3, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- Piña, Ireri (October 25, 2018). "Necesarios 35 mdp para solventar daños por "Willa"" [35 MDP required to address damages by "Willa"]. Contramuro (in Spanish). Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "Estiman en 6 mil millones de pesos los daños dejados por huracán Willa en Escuinapa". Noticias Digitales Sinaloa (in Spanish). February 6, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Espinosa, Gabriela (November 11, 2018). "Ascienden a $10 mil millones los daños que causó 'Willa' en Nayarit". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- United States Department of Commerce (1999). "South Texas Floods- October 17 – 22, 1998" (PDF). Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- "Floods in Southeast Texas, October 1994" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. January 1995. p. 1. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- "Guatemala - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2008. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- Tucson, Arizona National Weather Service (2008). "Tropical Storm Octave 1983". National Weather Service. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- Rotzull, Brenda (October 7, 1983). "Domestic News". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Oard, Michael (March 1, 2015). The New Weather Book (Wonders of Creation). Master Books. p. 54. ISBN 0890518610.

- "More flood victims found". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. September 28, 1982. p. 12. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- "Death from Salvadoran flood exceeds 1,200". Anchorage Daily News. September 24, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Mexico - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2008. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- "Hurricane hits Baja California". L.A. Times. October 1, 1982. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "Mexican state". Ellensburg Daily Record. October 2, 1982. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- "Adverse meteorological phenomena 3.2.2 KEY IN THE LAST 20 YEARS" (PDF). Elac. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- "Local National International". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. September 1, 1982. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- "Chilly weather follows behind Hurricane Paul". The Albany Herald. October 1, 1982. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- "El Salvador in Mouring". September 25, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Latest death toll from Flooding in El Salvador reaches 232". Williamson Daily News. September 21, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Latin Receive U.S. Disaster aid". Pittsburgh Press. September 22, 1982. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "World news". The Modest Bee. October 4, 1982. Retrieved August 11, 2011.