Hurricane Walaka

Hurricane Walaka was a Category 5 hurricane that brought high surf and a powerful storm surge to the Hawaiian Islands. Walaka was the nineteenth named storm, twelfth hurricane, eighth major hurricane, and second Category 5 hurricane of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season.[1]

| Category 5 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

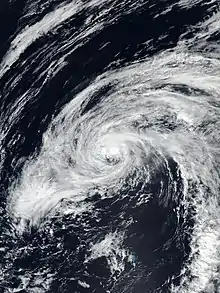

Hurricane Walaka at peak intensity south of Johnston Atoll on October 2 | |

| Formed | September 29, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 7, 2018 |

| (Extratropical after October 6) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 921 mbar (hPa); 27.2 inHg |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | Minimal |

| Areas affected | Johnston Atoll, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, East Island |

| Part of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season | |

The tropical cyclone originated from an area of low pressure that formed around 1,600 mi (2,575 km) south-southeast of Hawaii on September 24. The system tracked westward and moved into the Central Pacific Basin about a day later. The disturbance continued westward over the next few days, organizing into a tropical depression on September 29. Later that day, the system strengthened into a tropical storm, receiving the name Walaka. The storm rapidly intensified, becoming a hurricane on September 30 and a major hurricane by October 1. The cyclone took on a more northward track under the influence of a low-pressure system located to the north. Walaka peaked as a Category 5 hurricane, with winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a pressure of 921 mbar (27.20 inHg), early on October 2. An eyewall replacement cycle caused the hurricane to weaken, though it remained a major hurricane for the next couple of days. Afterward, less favorable conditions caused a steady weakening of the hurricane, and Walaka became extratropical on October 6, well to the north of the Hawaiian Islands. The storm's remnants accelerated northeastward, before dissipating on October 7.

Although the hurricane did not impact any major landmasses, it passed very close to the unpopulated Johnston Atoll as a strong Category 4 hurricane, where a hurricane warning was issued in advance of the storm. Four scientists there intended to ride out the storm on the island, but were evacuated before the storm hit. Walaka neared the far Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, but weakened considerably as it did so. East Island in the French Frigate Shoals suffered a direct hit and was completely destroyed. The storm caused significant damage to the nesting grounds for multiple endangered species; coral reefs in the region suffered considerable damage, displacing the local fish population. Several dozen people had to be rescued off the southern shore of Oahu as the storm brought high surf to the main Hawaiian Islands.

Meteorological history

On September 22, 2018, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecast that a low-pressure area would form around 130–140° west.[2] Two days later, a trough – an elongated region of low atmospheric pressure – formed around 1,600 mi (2,575 km) south-southeast of Hilo, Hawaii.[3] The disturbance entered the Central Pacific Basin on September 26 as a mixture of low-level clouds and larger cumulus clouds. A subtropical ridge located north of the Hawaiian Islands caused the system to track westward over the next few days. A surface low formed by 12:00 UTC on September 27 as the system was located 805 mi (1,295 km) southeast of Hilo. The system became Tropical Depression One-C around 12:00 UTC on September 29 while it was around 690 mi (1,110 km) south of Honolulu, Hawaii.[4] Convection or thunderstorm activity formed near the system's low-level circulation center, and a banding feature – significantly elongated, curved bands of rain clouds – became established over the southern and eastern portions of the depression. Six hours later, the system strengthened into a tropical storm, receiving the name Walaka from the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC).[4][5]

The nascent tropical storm was located in an environment of warm 84–86 °F (29–30 °C) sea surface temperatures, low vertical wind shear, and humid air.[4][5] After forming, the cyclone's banding features degraded, although its convection persisted. Meanwhile, the ridge continued to steer Walaka westward.[6] Around this time, Walaka began a stint of rapid intensification.[4] Convection became more abundant around the storm's low-level center during the morning of September 30.[7] Walaka's cloud tops cooled;[8] the tropical cyclone intensified into a hurricane by 18:00 UTC.[4] A cloud-filled eye emerged on visible satellite imagery by early October 1 as Walaka continued to strengthen.[9] Walaka became a Category 3 major hurricane around 12:00 UTC on October 1, the fourth storm to do so in the Central Pacific in 2018.[4] At that time, the hurricane possessed a prominent eye surrounded by a sizeable ring of cold clouds. Walaka turned towards the west-northwest as it moved around the southwestern edge of the ridge.[10] Walaka peaked as a Category 5 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 921 mbar (27.20 inHg), at 00:00 UTC on October 2. Walaka's peak intensity made it the second Category 5 hurricane of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season.[4] Around that time, the cyclone had a clear, 23-mile (37 km) wide eye surrounded by cool cloud tops.[11] Meanwhile, microwave imagery and ASCAT data showed the formation of concentric eyewalls, signaling that an eyewall replacement cycle had commenced. A strengthening upper-level low located north of Walaka was causing the hurricane to begin a more northward track.[4][12][13]

Walaka maintained its peak intensity for six hours before beginning to decay as a result of the eyewall replacement cycle. The cyclone continued to track northward under the influence of the upper-level low.[4][13] The hurricane weakened to a minimal Category 4 hurricane by 00:00 UTC on October 3. By that time, Walaka's eye had degraded on satellite imagery;[4] the eye had become cloud-filled, and the clouds making up the eyewall and central dense overcast had warmed.[14][15] Walaka passed about 45 mi (75 km) west of Johnston Island around 03:00 UTC.[16] After completing the eyewall cycle, Walaka reintensified slightly, reaching a secondary peak of 145 mph (230 km/h) around 12:00 UTC on October 3.[4] The cyclone's eye became increasingly delineated as the clouds comprising the eyewall cooled. Although the storm had restrengthened, increasing wind shear was thinning the northwestern eyewall.[17] Soon after, Walaka began to weaken once more as it advanced north-northeastward. Later on October 3, the western and southwestern eyewall eroded as a result of the wind shear. At the same time, upper-level cirrus outflow was disrupted in the southwestern and northeastern portions of the storm.[18] The already strong wind shear increased even further, peaking at 54 mph (87 km/h) around 00:00 UTC. Walaka's eye disappeared from visible satellite imagery and the southwestern portion of the low-level center became uncovered.[19]

Walaka made its closest approach to the French Frigate Shoals around 06:20 UTC on October 4. At that time, the Category 3 hurricane was located approximately 35 mi (55 km) to the west-northwest.[4] Environmental conditions deteriorated even further on October 4 as sea surface temperatures fell below 81 °F (27 °C) and ocean heat content decreased.[20] This caused Walaka to rapidly weaken; the hurricane fell below major hurricane intensity around 12:00 UTC and was a minimal Category 1 hurricane by 00:00 UTC on October 5.[4] Early on October 5, Walaka turned towards the northwest as it traced the northern boundary of the upper-level low. Convection associated with the storm continued to dissipate; the remaining thunderstorm activity was displaced northeast of the storm's low-level center.[21] The wind shear abated later on October 5, although sea surface temperatures along the remainder of the tropical storm's track were cooler than 77 °F (25 °C). As a result of the decreased shear, Walaka's low-level center was temporarily recovered by convection and the weakening trend slowed as the storm continued north-northwest.[4][22] By late October 5, the low-level center was completely exposed once more and the remaining convection had all but dissipated. Walaka turned towards the northeast, steered by an upper-level trough.[4][23] Walaka transitioned into an extratropical cyclone around 12:00 UTC on October 6 after having been deprived of thunderstorm activity.[4][24] The extratropical cyclone tracked over the open sea and dissipated by 18:00 UTC on October 7.[4]

Preparations and impact

As Walaka approached the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, a hurricane watch was issued for Johnston Atoll on September 30 and was upgraded to a hurricane warning on October 1. Early on October 2, a hurricane watch was issued for Nihoa to French Frigate Shoals to Maro Reef. Later in the day, a hurricane warning was issued for French Frigate Shoals to Maro Reef and a tropical storm warning was issued for Nihoa to French Frigate Shoals.[4] A crew of four scientists on the isolated Johnston Atoll had planned on riding out the storm in an evacuation shelter until the United States Fish and Wildlife Service sought an emergency evacuation on October 1. The United States Coast Guard flew a plane from Kalaeloa Airport to evacuate the personnel the next day.[25][26] Seven researchers studying Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles on French Frigate Shoals were evacuated to Honolulu on October 2.[27]

Walaka struck the northwestern Hawaiian Islands as a Category 3 hurricane on October 4.[4] A powerful storm surge accompanied the hurricane as it traversed the French Frigate Shoals. The small, low-lying East Island suffered a direct hit and was completely destroyed, sediment being scattered across coral reefs to the north. The island had served as one of the major nesting locations for the endangered green sea turtles, and critically endangered Hawaiian monk seals.[28] An estimated 19 percent of 2018's sea turtle nests on the island were lost, but all adult females tending the nests left before the storm. Approximately half of Hawaii's green sea turtles nested on the island, and Charles Littnan – director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's protected species division – stated it would take years for the implications of the island's loss to be fully understood.[29] By August 2019, satellite imagery showed that sand was beginning to reaccumulate on East Island.[30] Coral reefs near the French Frigate Shoals, Lisianski Island, and the Pearl and Hermes Atoll were substantially damaged, displacing the native fish population.[4]

Swells from Hurricane Walaka brought high surf to the main Hawiian Islands on October 4. Walaka produced a surf that was 6–12 ft (1.8–3.7 m) high along the southern and western shores of Niihau, Kauai, and Oahu. The southern shores of Molokai, Lanai, and Maui experienced waves approximately 5–8 ft (1.5–2.4 m) in height. Hawaii's Big Island endured a surf that was 6–10 ft (1.8–3.0 m) high on its western shores.[31] At least 81 people had to be rescued by lifeguards off the southern shore of Oahu.[32]

See also

- List of Category 5 Pacific hurricanes

- Hurricane Iniki (1992) – took a 90° northward turn, under the influence of an upper level trough[33]

- Hurricane Neki (2009) – Category 3 hurricane that affected the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument as a tropical storm.[34]

References

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved October 1, 2020. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Zelinsky, David (September 22, 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook: Eastern Pacific [500 PM PDT Mon Sep 22 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- Zelinsky, David (September 24, 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook: Eastern Pacific [500 PM PDT Mon Sep 24 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- Houston, Sam; Birchard, Thomas (June 9, 2020). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Walaka (PDF) (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Wroe, Derek (September 29, 2018). Tropical Storm Walaka Discussion Number 1 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Wroe, Derek (September 30, 2018). Tropical Storm Walaka Discussion Number 2 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Jelsema, Jon (September 30, 2018). Tropical Storm Walaka Discussion Number 3 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Powell, Jeff (September 30, 2018). Tropical Storm Walaka Discussion Number 5 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Powell, Jeff (October 1, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 6 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Jelsema, Jon (October 1, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 8 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Kodama, Kevin (October 1, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 9 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Kodama, Kevin (October 2, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 10 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Jelsema, Jon (October 2, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 12 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Brenchley, Chris (October 2, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 13 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Ballard, Robert (October 3, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 14...Corrected (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Ballard, Robert (October 3, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Advisory Number 14 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Houston, Sam (October 3, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 16...Corrected (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Brenchley, Chris (October 3, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 17 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Brenchley, Chris (October 4, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 18 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Houston, Sam (October 4, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 20 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Wroe, Derek (October 5, 2018). Hurricane Walaka Discussion Number 22 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Jelsema, Jon (October 5, 2018). Tropical Storm Walaka Discussion Number 23 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Powell, Jeff (October 5, 2018). Tropical Storm Walaka Discussion Number 25 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Houston, Sam (October 6, 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Walaka Discussion Number 28 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Magee, David (October 2, 2018). "Hurricane Walaka Threatens Seabirds With Direct Hit on Johnston Atoll in Pacific". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "Coast Guard evacuates Fish and Wildlife crew off Johnston Atoll ahead of Hurricane Walaka". Coast Guard News. October 2, 2018. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "7 Researchers Evacuated From Pacific Atoll as Storm Nears". The New York Times. Associated Press. October 3, 2018. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Milman, Oliver (October 24, 2018). "Hawaiian island erased by powerful hurricane: 'The loss is a huge blow'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- D’Angelo, Chris (October 23, 2018). "Remote Hawaiian Island Wiped Off The Map". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Eagle, Nathan (August 15, 2019). "NOAA: 'The Reefs Weren't Damaged, They Were Just Gone'". Honolulu Civil Beat. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Event: High Surf in Kohala, Hawaii [2018-10-04 06:00 HST-10] (Report). Storm Events Database. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Gonzales, Melody (October 4, 2018). "Lifeguards rescue dozens as Walaka kicks up surf on Oahu's south shore". KITV 4 Island News. ABC. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- The 1992 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Wroe, Derek (February 5, 2010). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Neki (PDF) (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Walaka. |

- The Central Pacific Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Walaka

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Weather Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Weather Service.