Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is an increase in parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels in the blood.[1][4] This occurs from a disorder either within the parathyroid glands (primary hyperparathyroidism) or outside the parathyroid glands (secondary hyperparathyroidism).[1] Symptoms of hyperparathyroidism are caused by inappropriately normal or elevated blood calcium leaving the bones and flowing into the blood stream in response to increased production of parathyroid hormone.[1] In healthy people, when blood calcium levels are high, parathyroid hormone levels should be low. With long-standing hyperparathyroidism, the most common symptom is kidney stones.[1] Other symptoms may include bone pain, weakness, depression, confusion, and increased urination.[1][2] Both primary and secondary may result in osteoporosis (weakening of the bones).[2][3]

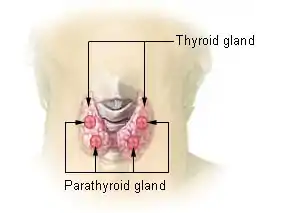

| Hyperparathyroidism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Thyroid and parathyroid | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | None, kidney stones, weakness, depression, bone pains, confusion, increased urination[1][2][3] |

| Complications | Osteoporosis[2][3] |

| Usual onset | 50 to 60[2] |

| Types | Primary, secondary |

| Causes | Primary: parathyroid adenoma, multiple benign tumors, parathyroid cancer[1][2] Secondary: vitamin D deficiency, chronic kidney disease, low blood calcium[1] |

| Diagnostic method | High blood calcium and high PTH levels[2] |

| Treatment | Monitoring, surgery, intravenous normal saline, cinacalcet[1][2] |

| Frequency | ~2 per 1,000[3] |

In 80% of cases, primary hyperparathyroidism is due to a single benign tumor known as a parathyroid adenoma.[1][2] Most of the remainder are due to several of these adenomas.[1][2] Very rarely it may be due to parathyroid cancer.[2] Secondary hyperparathyroidism typically occurs due to vitamin D deficiency, chronic kidney disease, or other causes of low blood calcium.[1] The diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism is made by finding elevated calcium and PTH in the blood.[2]

Primary hyperparathyroidism may only be cured by removing the adenoma or overactive parathyroid glands.[5][1][2] In those without symptoms, mildly increased blood calcium levels, normal kidneys, and normal bone density monitoring may be all that is required.[2] The medication cinacalcet may also be used to decrease PTH levels in those unable to have surgery although it is not a cure.[2] In those with very high blood calcium levels, treatment may include large amounts of intravenous normal saline.[1] Low vitamin D should be corrected in those with secondary hyperparathyroidism but low Vitamin D pre-surgery is controversial for those with primary hyperparathyroidism.[6] Low vitamin D levels should be corrected post-parathyroidectomy.[2]

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common type.[1] In the developed world, between one and four per thousand people are affected.[3] It occurs three times more often in women than men and is often diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 60 but is not uncommon before then.[2] The disease was first described in the 1700s.[7] In the late 1800s, it was determined to be related to the parathyroid.[7] Surgery as a treatment was first carried out in 1925.[7]

Signs and symptoms

In primary hyperparathyroidism, about 75% of people are 'asymptomatic'.[1] While most primary patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, 'asymptomatic' is poorly defined and represents only those without "obvious clinical sequalae" such as kidney stones, bone disease, or hypercalcemic crisis.[5] These 'asymptomatic' patients may have other symptoms such as depression, anxiety, gastrointestinal distress, and neuromuscular problems that are not counted as symptoms.[5] The problem is often picked up incidentally during blood work for other reasons, and the test results show a higher amount of calcium in the blood than normal.[3] Many people only have non-specific symptoms.

Common manifestations of hypercalcemia include weakness and fatigue, depression, bone pain, muscle soreness (myalgias), decreased appetite, feelings of nausea and vomiting, constipation, pancreatitis, polyuria, polydipsia, cognitive impairment, kidney stones ([nb 1]), vertigo and osteopenia or osteoporosis.[10][11] A history of acquired racquet nails (brachyonychia) may be indicative of bone resorption.[12] Parathyroid adenomas are very rarely detectable on clinical examination. Surgical removal of a parathyroid tumor eliminates the symptoms in most patients.

In secondary hyperparathyroidism due to lack of Vitamin D absorption, the parathyroid gland is behaving normally; clinical problems are due to bone resorption and manifest as bone syndromes such as rickets, osteomalacia, and renal osteodystrophy.[13]

Causes

Radiation exposure increases the risk of primary hyperparathyroidism.[1] A number of genetic conditions including multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes also increase the risk.[1] Parathyroid adenomas have been linked with DDT although a causal link has not yet been established.[14]

Mechanism

Normal parathyroid glands measure the ionized calcium (Ca2+) concentration in the blood and secrete parathyroid hormone accordingly; if the ionized calcium rises above normal, the secretion of PTH is decreased, whereas when the Ca2+ level falls, parathyroid hormone secretion is increased.[8]

Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs if the calcium level is abnormally low. The normal glands respond by secreting parathyroid hormone at a persistently high rate. This typically occurs when the 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels in the blood are low and hypocalcemia is present. A lack of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 can result from a deficient dietary intake of vitamin D, or from a lack of exposure of the skin to sunlight, so the body cannot make its own vitamin D from cholesterol.[15] The resulting hypovitaminosis D is usually due to a partial combination of both factors. Vitamin D3 (or cholecalciferol) is converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (or calcidiol) by the liver, from where it is transported via the circulation to the kidneys, and it is converted into the active hormone, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3.[8][15] Thus, a third cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism is chronic kidney disease. Here the ability to manufacture 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 is compromised, resulting in hypocalcemia.

Diagnosis

The gold standard of diagnosis is the PTH immunoassay. Once an elevated PTH has been confirmed, the goal of diagnosis is to determine whether the hyperparathyroidism is primary or secondary in origin by obtaining a serum calcium level:

| Serum calcium | Phosphate | ALP | PTH | Likely type |

| ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | Primary hyperparathyroidism[16] |

| ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Secondary hyperparathyroidism[16] |

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism has a high PTH and a high serum calcium. It is differentiated from primary hyperparathyroidism by a history of chronic kidney failure and secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Hyperparathyroidism can cause hyperchloremia and increase renal bicarbonate loss, which may result in a normal anion gap metabolic acidosis.[7]

Differential diagnosis

Familial benign hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia can present with similar lab changes.[1] In this condition, the calcium creatinine clearance ratio, however, is typically under 0.01.[1]

Intact PTH

In primary hyperparathyroidism, parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels are either elevated or "inappropriately normal" in the presence of elevated calcium. Typically, PTH levels vary greatly over time in the affected patient and (as with Ca and Ca++ levels) must be retested several times to see the pattern. The currently accepted test for PTH is intact PTH, which detects only relatively intact and biologically active PTH molecules. Older tests often detected other, inactive fragments. Even intact PTH may be inaccurate in patients with kidney dysfunction. Intact pth blood tests may be falsely low if biotin has been ingested in the previous few days prior to the blood test.[17]

Calcium levels

In cases of primary hyperparathyroidism or tertiary hyperparathyroidism, heightened PTH leads to increased serum calcium (hypercalcemia) due to:

- increased bone resorption, allowing flow of calcium from bone to blood

- reduced kidney clearance of calcium

- increased intestinal calcium absorption

Serum phosphate

In primary hyperparathyroidism, serum phosphate levels are abnormally low as a result of decreased reabsorption of phosphate in the kidney tubules. However, this is only present in about 50% of cases. This contrasts with secondary hyperparathyroidism, in which serum phosphate levels are generally elevated because of kidney disease.

Alkaline phosphatase

Alkaline phosphatase levels are usually elevated in hyperparathyroidism. In primary hyperparathyroidism, levels may remain within the normal range, but this is inappropriately normal given the increased levels of plasma calcium.

Nuclear medicine

A technetium sestamibi scan is a procedure in nuclear medicine that identifies hyperparathyroidism (or parathyroid adenoma).[18] It is used by surgeons to locate ectopic parathyroid adenomas, most commonly found in the anterior mediastinum.

Primary

Primary hyperparathyroidism results from a hyperfunction of the parathyroid glands themselves. The oversecretion of PTH is due to a parathyroid adenoma, parathyroid hyperplasia, or rarely, a parathyroid carcinoma. This disease is often characterized by the quartet stones, bones, groans, and psychiatric overtones referring to the presence of kidney stones, hypercalcemia, constipation, and peptic ulcers, as well as depression, respectively.[19][20]

In a minority of cases, this occurs as part of a multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome, either type 1 (caused by a mutation in the gene MEN1) or type 2a (caused by a mutation in the gene RET), which is also associated with the adrenal tumor pheochromcytoma. Other mutations that have been linked to parathyroid neoplasia include mutations in the genes HRPT2 and CASR.[21][22]

Patients with bipolar disorder who are receiving long-term lithium treatment are at increased risk for hyperparathyroidism.[23] Elevated calcium levels are found in 15% to 20% of patients who have been taking lithium long-term. However, only a few of these patients have significantly elevated levels of parathyroid hormone and clinical symptoms of hyperparathyroidism. Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism is usually caused by a single parathyroid adenoma.[23]

Secondary

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is due to physiological (i.e. appropriate) secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) by the parathyroid glands in response to hypocalcemia (low blood calcium levels). The most common causes are vitamin D deficiency[24] (caused by lack of sunlight, diet or malabsorption) and chronic kidney failure.

Lack of vitamin D leads to reduced calcium absorption by the intestine leading to hypocalcemia and increased parathyroid hormone secretion. This increases bone resorption. In chronic kidney failure the problem is more specifically failure to convert vitamin D to its active form in the kidney. The bone disease in secondary hyperparathyroidism caused by kidney failure is termed renal osteodystrophy.

Tertiary

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism is seen in those with long-term secondary hyperparathyroidism, which eventually leads to hyperplasia of the parathyroid glands and a loss of response to serum calcium levels. This disorder is most often seen in patients with end-stage kidney disease and is an autonomous activity.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the type of hyperparathyroidism encountered.

Primary

People with primary hyperparathyroidism who are symptomatic benefit from parathyroidectomy—surgery to remove the parathyroid tumor (parathyroid adenoma). Indications for surgery are:[25]

- Symptomatic hyperparathyroidism

- Asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism with any of the following:

- 24-hour urinary calcium > 400 mg (see footnote, below)

- serum calcium > 1 mg/dl above upper limit of normal

- Creatinine clearance > 30% below normal for patient's age

- Bone density > 2.5 standard deviations below peak (i.e., T-score of -2.5)

- People age < 50

Surgery can rarely result in hypoparathyroidism.

Secondary

In people with secondary hyperparathyroidism, the high PTH levels are an appropriate response to low calcium and treatment must be directed at the underlying cause of this (usually vitamin D deficiency or chronic kidney failure). If this is successful, PTH levels return to normal levels, unless PTH secretion has become autonomous (tertiary hyperparathyroidism).

Calcimimetics

A calcimimetic (such as cinacalcet) is a potential therapy for some people with severe hypercalcemia and primary hyperparathyroidism who are unable to undergo parathyroidectomy, and for secondary hyperparathyroidism on dialysis.[26][27] Treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism with a calcimimetic in those on dialysis for CKD does not alter the risk of early death; however, it does decrease the likelihood of needing a parathyroidectomy.[28] Treatment carries the risk of low blood calcium levels and vomiting.[28]

History

The oldest known case was found in a cadaver from an Early Neolithic cemetery in southwest Germany.[29]

Notes

- Although parathyroid hormone (PTH) promotes the reabsorption of calcium from the kidneys' tubular fluid, thus decreasing the rate of urinary calcium excretion, its effect is only noticeable at any given plasma ionized calcium concentration. The primary determinant of the amount of calcium excreted into the urine per day is the plasma ionized calcium concentration. Thus, in primary hyperparathyroidism, the quantity of calcium excreted in the urine per day is increased despite the high levels of PTH in the blood, because hyperparathyroidism results in hypercalcemia, which increases the urinary calcium concentration (hypercalcuria). Kidney stones are, therefore, often a first indication of hyperparathyroidism, especially since the hypercalcuria is accompanied by an increase in urinary phosphate excretion (a direct result of the high plasma PTH levels). Together, the calcium and phosphate tend to precipitate out as water-insoluble salts, which readily form solid “stones”.[8][9]

References

- Fraser WD (July 2009). "Hyperparathyroidism". Lancet. 374 (9684): 145–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60507-9. PMID 19595349. S2CID 208793932.

- "Primary Hyperparathyroidism". NIDDK. August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Michels TC, Kelly KM (August 2013). "Parathyroid disorders". American Family Physician. 88 (4): 249–57. PMID 23944728.

- Allerheiligen DA, Schoeber J, Houston RE, Mohl VK, Wildman KM (April 1998). "Hyperparathyroidism". American Family Physician. 57 (8): 1795–802, 1807–8. PMID 9575320.

- McDow AD, Sippel RS (2018-01-01). "Should Symptoms Be Considered an Indication for Parathyroidectomy in Primary Hyperparathyroidism?". Clinical Medicine Insights. Endocrinology and Diabetes. 11: 1179551418785135. doi:10.1177/1179551418785135. PMC 6043916. PMID 30013413.

- Randle RW, Balentine CJ, Wendt E, Schneider DF, Chen H, Sippel RS (July 2016). "Should vitamin D deficiency be corrected before parathyroidectomy?". The Journal of Surgical Research. 204 (1): 94–100. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.022. PMID 27451873.

- Gasparri G, Camandona M, Palestini N (2015). Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Updates. Springer. ISBN 9788847057586. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Blaine J, Chonchol M, Levi M (July 2015). "Renal control of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium homeostasis". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 10 (7): 1257–72. doi:10.2215/CJN.09750913. PMC 4491294. PMID 25287933.

- Harrison TR, Adams RD, Bennett Jr IL, Resnick WH, Thorn GW, Wintrobe MM (1958). "Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders.". Principles of Internal Medicine (Third ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 575–578.

- Hyperparathyroidism Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine. National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service. May 2006.

- McKenna K, Rahman K, Parham K (November 2020). "Otoconia degeneration as a consequence of primary hyperparathyroidism". Medical Hypotheses. 144: 109982. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109982. PMID 32531542.

- Baran R, Turkmani MG, Mubki T (February 2014). "Acquired racquet nails: a useful sign of hyperparathyroidism". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 28 (2): 257–9. doi:10.1111/jdv.12187. PMID 23682576.

- "Secondary Hyperparathyroidism: What is Secondary Hyperparathyroidism? Secondary Hyperparathyroidism Symptoms, Treatment, Diagnosis - UCLA". www.uclahealth.org. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- Hu X, Saunders N, Safley S, Smith MR, Liang Y, Tran V, et al. (January 2021). "Environmental chemicals and metabolic disruption in primary and secondary human parathyroid tumors". Surgery. 169 (1): 102–108. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2020.06.010. PMID 32771296.

- Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 707. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- Le T, Bhushan V, Sochat M, Kallianos K, Chavda Y, Zureick AH, Kalani M (2017). First aid for the USMLE step 1 2017. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1259837630.

- Waghray A, Milas M, Nyalakonda K, Siperstein AE (2013). "Falsely low parathyroid hormone secondary to biotin interference: a case series". Endocrine Practice. 19 (3): 451–5. doi:10.4158/EP12158.OR. PMID 23337137.

- Neish AS, Nagel JS, Holman BL. "Parathyroid Adenoma". BrighamRAD Teaching Case Database. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- Carroll MF, Schade DS (May 2003). "A practical approach to hypercalcemia". American Family Physician. 67 (9): 1959–66. PMID 12751658. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014.

his constellation of symptoms has led to the mnemonic “Stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans,” which is used to recall the signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia, particularly as a result of primary hyperparathyroidism.

- McConnell TH (2007). The Nature of Disease: Pathology for the Health Professions. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 466. ISBN 9780781753173.

"Stones" refers to kidney stones, "bones" to associated destructive bone changes, "groans" to the pain of stomach and peptic ulcers that occur in some cases, and "moans" to the depression that frequently accompanies the disease and is often its first and most prominent manifestation.

- Marx SJ (2011). "Hyperparathyroid genes: sequences reveal answers and questions". Endocrine Practice. 17 Suppl 3: 18–27. doi:10.4158/EP11067.RA. PMC 3484688. PMID 21454225.

- Sulaiman L, Nilsson IL, Juhlin CC, Haglund F, Höög A, Larsson C, Hashemi J (June 2012). "Genetic characterization of large parathyroid adenomas". Endocrine-Related Cancer. 19 (3): 389–407. doi:10.1530/ERC-11-0140. PMC 3359501. PMID 22454399.

- Pomerantz JM (2010). "Hyperparathyroidism Resulting From Lithium Treatment Remains Underrecognized". Drug Benefit Trends. 22: 62–63. Archived from the original on 2010-07-01.

- Lips P (August 2001). "Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications". Endocrine Reviews. 22 (4): 477–501. doi:10.1210/er.22.4.477. PMID 11493580.

- Bilezikian JP, Silverberg SJ (April 2004). "Clinical practice. Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism". The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (17): 1746–51. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp032200. PMC 3987990. PMID 15103001.

- "Sensipar: Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Amgen Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- Ott SM (April 1998). "Calcimimetics--new drugs with the potential to control hyperparathyroidism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 83 (4): 1080–2. doi:10.1210/jc.83.4.1080. PMID 9543121.

- Ballinger AE, Palmer SC, Nistor I, Craig JC, Strippoli GF (9 December 2014). "Calcimimetics for secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD006254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006254.pub2. PMID 25490118.

- Zink AR, Panzer S, Fesq-Martin M, Burger-Heinrich E, Wahl J, Nerlich AG (January 2005). "Evidence for a 7000-year-old case of primary hyperparathyroidism". JAMA. 293 (1): 40–2. doi:10.1001/jama.293.1.40-c. PMID 15632333.

External links

- Hyperparathyroidism at Curlie

- Overview at Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service

- Insogna KL (September 2018). "Primary Hyperparathyroidism". The New England Journal of Medicine (Review). 379 (11): 1050–1059. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.322.5883. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1714213. PMID 30207907. S2CID 205069527.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |