IX Corps (United States)

IX Corps was a corps of the United States Army. For most of its operational history, IX Corps was headquartered in or around Japan and subordinate to US Army commands in the Far East.

| IX Corps | |

|---|---|

Shoulder sleeve insignia of IX Corps | |

| Active | 1940–94 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Motto(s) | Pride of the Pacific |

| Engagements | World War II Korean War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Kenyon A. Joyce (1940–42) Charles W. Ryder (1944–48) Leland Hobbs (1949–50) Frank W. Milburn (1950) John B. Coulter (1950–51) Bryant Moore (1951) Oliver P. Smith (1951) William M. Hoge(1951) Willard G. Wyman (1951–52) Joseph P. Cleland (1952) Reuben E. Jenkins (1952–53) Samuel T. Williams (1954) Carter B. Magruder (1954–55) James E. Moore (1955–58) John R. Guthrie (1975–77)[1] |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |  |

| U.S. Corps (1939–present) | |

|---|---|

| Previous | Next |

| VIII Corps (United States) | X Corps (United States) |

Created following World War I, the corps was not activated for use until just before World War II almost 20 years later. The corps spent most of World War II in charge of defenses on the West Coast of the United States, before moving to Hawaii and Leyte to plan and organize operations for US forces advancing across the Pacific. Following the end of the war, IX Corps participated in the occupation of mainland Japan.

The corps' only combat came in the Korean War. It is best known for its exploits as a senior command of the Eighth United States Army, commanding front line UN forces in numerous offensives and counteroffensives throughout the war. The corps served on the front lines for most of the conflict and took command of several combat divisions at a time. Following the end of the Korean War, IX Corps remained in Korea for several years until it was moved to Japan. The corps spent almost 40 years as an administrative command of the US Army forces there, overseeing administrative functions but no combat. It was finally inactivated and consolidated in 1994.

History

World War I

IX Corps was formed from 25 to 29 November 1918 in Ligny-en-Barrois, France.[2] It was demobilized in France on 5 May 1919.[3] IX Corps was subordinate to Second United States Army, and after moving its headquarters to Saint-Mihiel, and commanded forces along the armistice line between Jonville-en-Woëvre and Fresnes-en-Woëvre until its deactivation.[4] Adelbert Cronkhite was the first corps commander, and William K. Naylor the first chief of staff.[5] Subsequent World War I commanders included Joseph E. Kuhn.[6]

Post-World War I

The IX Corps headquarters was first constituted on 29 July 1921 in the organized reserves, a new corps formation intended to complement the existing corps commands in the active duty component of the force by providing command to reserve units.[7] It was assigned a shoulder sleeve insignia shortly thereafter.[8] Though the corps was not activated, it remained on the organizational rolls of the Army, to be called on when needed. On 1 October 1933, the corps was moved to the active duty roster, though it remained deactivated.[7]

World War II

The corps headquarters was finally activated on 24 October 1940 at Fort Lewis, Washington as part of a large buildup of the US Army in response to conflicts around the world.[7] It immediately began training of combat units in preparation for deployment.[9] One year later, IX Corps took command of the Camp Murray staging area in Washington, responsible for training Army National Guard forces in addition to its responsibilities training active duty and reserve units.[10]

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in late 1941, IX Corps was assigned to defensive duties on the West Coast of the United States, specifically the central and northern regions of the coast.[9] The corps oversaw defenses on the West Coast for the majority of the war, but in 1944 it was moved to Fort McPherson, Georgia in preparation for deployment overseas.[10]

Planning

The corps trained at Fort McPherson in preparation for deployment to the Pacific Theater of Operations. On 25 September 1944, the corps closed headquarters at Fort McPherson and moved to Hawaii.[9] When it arrived in Hawaii, IX Corps was put under the command of the Tenth United States Army. Under the Tenth Army, IX Corps was assigned two missions. In 1944, it was primarily concerned with formulating plans for an invasion of the coastal regions of Japanese-held China. Later in 1944 and early 1945, it was placed in charge of preparing the rest of the Tenth Army for movement to Okinawa in preparation for an invasion of the island, which was launched in April 1945.[10]

When General of the Army Douglas MacArthur took overall command of Pacific Forces, IX Corps was moved to Leyte in the Philippine Islands and was assigned to the Sixth United States Army in July 1945.[10] In Leyte, the corps was tasked with the planning of Operation Downfall, the invasion of mainland Japan, specifically the island of Kyushu. It was also tasked with planning occupation once Japan surrendered.[9] IX Corps was assigned as one of four Corps under the command of the Sixth Army, with a strength of 14 divisions. With the 77th Infantry Division, the 81st Infantry Division and 98th Infantry Division, a force of 79,000 men, IX Corps would serve as the Sixth Army's reserve force during the initial invasion.[11] Before the assault could be launched, Japan surrendered in August 1945, following the use of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[12]

Occupation

Following the surrender, IX Corps was assigned command of occupation forces on the northern island of Hokkaidō. IX Corps transferred its headquarters in October 1945 to Sapporo for occupation duties.[10] The next few years were a period during which the terms of the surrender were supervised and enforced; Japanese military installations and material were seized, troops were disarmed and discharged, and weapons of warfare disposed of. The duties of the occupation force included conversion of industry, repatriation of foreign nationals, and supervision of the complex features of all phases of Japanese government, economics, education, and industry.[13]

As the occupation duties were accomplished, the occupation force continued to downsize as more troops returned home and their units were inactivated. By 1950, the Sixth Army had left Japan, and the occupation force was reduced to the Eighth United States Army commanding two corps and four under-strength divisions; the I Corps, commanding the 24th Infantry Division and 25th Infantry Division, and the IX Corps, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division and the 7th Infantry Division.[14] IX Corps had been moved to Sendai as the occupation forces shifted as a result of the downsizing.[15] As part of further downsizing, IX Corps was inactivated on 28 March 1950, and its command responsibilities were consolidated with other units.[7]

Korean War

Only a few months later, the Korean War began, and units from Japan began streaming into South Korea. The Eighth Army, taking charge of the conflict, requested the activation of three corps headquarters for its growing command of UN forces. IX Corps was activated on 10 August 1950 at Fort Sheridan, Illinois.[7] Most of its personnel were transferred from the headquarters of the Fifth United States Army.[16]

Pusan Perimeter

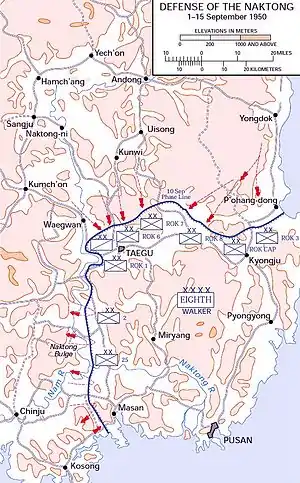

IX Corps arrived at the Pusan Perimeter in Korea on 22 September 1950, and became operational the next day when it took command of the 2nd Infantry Division and 25th Infantry Division.[16][17] It took charge of the western flank of the perimeter, defending the Naktong River area against attacking North Korean Korean People's Army (KPA) units.[18]

Amphibious landings at Inchon by X Corps hit KPA forces from behind, allowing I Corps to breakout from the Pusan perimeter starting on 16 September.[19] Four days later I Corps troops began a general offensive northward against crumbling KPA opposition to establish contact with forces of the 7th Infantry Division driving southward from the beachhead. Major elements of the KPA were destroyed and cut off in this aggressive penetration; the link-up was effected south of Suwon on 26 September.[20] The offensive was continued northwards, past Seoul, and across the 38th Parallel into North Korea on 1 October. The momentum of the attack was maintained, and the race to the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, ended on 19 October when elements of the Republic of Korea Army (ROK) 1st Infantry Division and the US 1st Cavalry Division captured the city. The advance continued, but against unexpectedly stiffening resistance. The Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) entered the war on the side of North Korea, making their first attacks in late October. By the end of October the city of Chongju, 40 miles (64 km) from the Yalu River border of North Korea, had been captured.[21] IX Corps advanced in the center of the Army, with I Corps along the west coast and X Corps operating independently further east. Commanders hoped the offensive would end the war "by Christmas."[22]

Chinese intervention

The UN forces renewed their offensive on 24 November before being stopped by the PVA Second Phase Offensive starting on 25 November with PVA forces penetrating the corps' rear from its exposed east flank.[23] The 2nd Infantry Division, at the front of IX Corp's advance in Kunuri, was overwhelmed from all sides by PVA forces of the 40th Army Corps and elements from the 38th Army Corps on 29 November in the Battle of Kunuri.[24] By 1 December, the division was almost completely destroyed; it lost virtually all of its heavy equipment and vehicles, as well as suffering 4,940 men killed or missing.[25] The 25th Infantry Division, on its western flank, was also hit by overwhelming PVA forces of the 39th Army Corps, facing strong attacks and suffering heavy casualties and losses in equipment in the Battle of Ch'ongch'on River.[24] However, it was spared the same losses as the 2nd Infantry Division by escaping across the Ch'ongch'on River.[23] The Eighth Army suffered heavy casualties, ordering a complete withdrawal to the Imjin River, south of the 38th Parallel, having been destabilised by the overwhelming PVA forces.[25] IX Corps retreated along the western coast to safety via Anju.[26]

In the wake of the retreat, the disorganized Eighth Army regrouped and re-formed in late December. The 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions had suffered so many losses that both divisions were designated combat ineffective and were relegated to the Eighth Army's reserve to rebuild. IX Corps was then assigned the 1st Cavalry Division, 24th Infantry Division, 1st Marine Division and ROK 6th Infantry Division, as well as the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team.[16] The corps' American forces were also reinforced at this point with battalions from Greece and the Philippines, as well as the 27th Commonwealth Brigade.[27]

On 1 January 1951, 500,000 PVA troops attacked the Eighth Army's line at the Imjin River, forcing them back 50 miles (80 km) and allowing the PVA to capture Seoul.[25] The PVA eventually advanced too far for their supply lines to adequately support them, and their attack stalled. The Eighth Army, battered by the PVA assault, began to prepare counteroffensives to retake lost ground and keep the retreating PVA forces from being able to rest.[28][29]

Following the establishment of defenses south of the capital city, General Matthew B. Ridgway ordered I, IX and X Corps to conduct a general counteroffensive against the PVA forces on 25 January, Operation Thunderbolt. The three corps advanced north with IX Corps at the center of the line, on both sides of the Han River.[30][31] The corps were to advance steadily northward, protected by heavy artillery and close air support, until they captured Seoul.[32] IX Corps was tasked with capturing Chipyong-ni, southeast of Seoul while providing support to the other two corps. However, it encountered stiff resistance from PVA forces dug into the hilly country around Chipyong-ni and was still bogged down in combat by 2 February. PVA forces had established machine gun nests in the hillside and mined roads to slow the corps' advance.[33] In response, X Corps launched Operation Roundup, hoping to take pressure off of IX Corps and to force the PVA to abandon Seoul.[34]

Between February and March, the corps participated in Operation Killer, pushing PVA forces north of the Han River.[35] This operation was quickly followed up with Operation Ripper, which retook Seoul in March.[36] After this, Operations Rugged and Operation Dauntless in April saw Eighth Army forces advance north of the 38th Parallel and reestablish themselves along the Kansas Line and Utah Line, respectively.[30] In March, the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team and the 1st Marine Division were reassigned, and the corps was given command of the 7th Infantry Division and the ROK 2nd Infantry Division in their place.[16]

In late April, the PVA launched a major counterattack.[37] 486,000 PVA troops assaulted I Corps and IX Corps' sector of the lines. Most of the UN forces were able to hold their ground, but the PVA broke through at Kapyong, where the ROK 6th Division was destroyed by the PVA 13th Army Corps, which penetrated the line and threatened to encircle the American divisions to the west.[38] The 1st Marine Division and 27th British Commonwealth Brigade were able to drive the 13th Army Corps back while the 24th and 25th Divisions withdrew on 25 April.[39] The line was pushed back to Seoul but managed to hold.[39] A second offensive the next month was similarly unsuccessful, as PVA and KPA forces suffered heavy casualties but were unable to push back the Eighth Army forces.[40] In May-June the UN launched another counteroffensive erasing most of the PVA gains.[41][42]

Stalemate

In September, the UN Forces launched another counteroffensive with the 24th Infantry Division at the center of the line, west of the Hwachon Reservoir. Subsequently, three of I Corps divisions advanced behind the 24th Infantry Division in Operation Commando.[43] Flanked by the ROK 2nd and 6th Divisions, the 24th advanced past Kumwha, engaging the PVA20th and 27th Armies.[43] These attacks were fierce, though PVA resistance was not as strong as it had been in previous offensives.[44] In November, the PVA attempted to counter this attack, but were unsuccessful. It was at this point, after several successive counteroffensives that saw both sides fighting intensely over the same ground, that the two sides started serious peace negotiations.[45] In January 1952, IX Corps was again reorganized, now containing the 7th Infantry Division and the newly arrived 45th Infantry Division. Two months later, it was reorganized with the 2nd Infantry Division, the 40th Infantry Division, and the ROK 2nd, 3rd and Capital Divisions.[16]

In October 1952, PVA forces conducted a large offensive against IX Corps' sector, against the hilly countryside around the Iron Triangle region of Cheorwon, Kumhwa, and Pyongyang. The PVA 8th Field Army sent heavy assaults against the ROK forces guarding Hill 395 in the Battle of White Horse.[46] At the same time, PVA forces attacked Arrowhead Hill, which was held by the 2nd Infantry Division 2 miles (3.2 km) away. Both hills changed hands several times, but after two weeks and almost 10,000 casualties, the PVA were unsuccessful in capturing either objective and withdrew.[47]

On 14 October 1952, IX Corps launched an offensive, Operation Showdown, intended to improve its defensive lines by capturing a complex of hills and force PVA lines back. This complex included Pike's Peak, Jane Russell Hill, Sandy Hill and Triangle Hill, northeast of Kumhwa. The 7th Infantry Division advanced, encountering resistance from the PVA 15th Field Army.[48] In the ensuing Battle of Triangle Hill, the four hills were captured and recaptured by both sides several times in the heaviest fighting that year.[49] Eventually, the UN forces withdrew having been unsuccessful in capturing their objectives. UN forces suffered 9,000 killed and the PVA suffered 19,000 killed or wounded during the fighting.[50] The result of the battle had only been a slight improvement in IX Corps' positions, as PVA positions had been too well fortified for the UN forces to take and hold the ground.[51] For the remainder of the year, UN and PVA forces both conducted a series of smaller raids on each other's lines, avoiding major conflicts, as armistice negotiations continued unsuccessfully.[52] In November, the PVA launched another offensive to retake ground lost during these operations, which was again repulsed by UN forces.[53]

In January 1953, IX Corps was reorganized for the last time and now consisted entirely of ROK forces. It retained command of the ROK 3rd Infantry Division and Capital Division, and gained command of the 9th Infantry Division.[16] The corps maintained a position around Chorwon, flanked to the west by I Corps and to the east by ROK II Corps.[54] Though ROK II Corps saw a major attack against its lines in July 1953, IX Corps and its divisions only fought in limited engagements, usually with company-sized formations attacking or defending fortified positions against the PVA until the end of the war.[55] No major attacks against the corps were conducted through 1953, until the armistice was signed in July, ending the war.[56]

After Korea

Following the armistice, IX Corps remained on the front lines in Korea in case hostilities erupted again. On 1 January 1954, it was reassigned from the Eighth Army to the Far East United States Army Forces.[9] Camp Sendai was Headquarters XVI and then IX Corps during the 1950s. In November 1956, over three years after the signing of the armistice, IX Corps headquarters left the front lines, moving to Fort Buckner, Okinawa, and the divisions under its command were shifted to the command of other headquarters.[16] There, as a part of consolidation of US forces in the region, IX Corps merged with the US Army's Ryukyu Command to form a joint command element on 1 January 1957. The command oversaw administrative duties of US forces in the Ryukyu Islands area.[9]

On 2 February 1956, IX Corps moved from mainland Japan to Fort Buckner, Okinawa, where it merged with Headquarters Ryukyus Command, to form HQ RYCOM/IX Corps on 1 January 1957. The Army had previously in the late 1940s formed Ryukyu Command from the previous Okinawa Base Command.

In 1961, part of the IX Corps was split into the 9th Regional Support Command, subordinate to U.S. Army Pacific. Though the 9th Regional Support Command was an independent unit, it continued to operate closely with IX Corps.[10] It received a distinctive unit insignia in 1969.[8]

A major change in the Army's organization in the Pacific occurred on 15 May 1972, in conjunction with the return of Okinawa to Japanese control after twenty-seven years of administration by the United States. Under the complex reorganization that accompanied reversion, Headquarters, IX U.S. Army Corps, was transferred from Okinawa and collocated with Headquarters, U.S. Army Japan, to form Headquarters, U.S. Army, Japan/IX Corps, at Camp Zama, Japan. There, its responsibilities included administrative oversight of US forces as well as conducting training and exercises with US and other units in the region.[9] On Okinawa, Headquarters, U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, and Headquarters, 2d Logistical Command, were inactivated.

To command and support all Army units on Okinawa and perform the theater logistic functions for United States and allied forces in the Pacific, U.S. Army Base Command, Okinawa was established as a major subordinate command of U.S. Army Japan on 15 May 1972. The command was reorganized as U.S. Army Garrison Okinawa and was reorganized in 1978 as U.S. Army Support Activity.[57] This was again changed back to U.S. Army Garrison Okinawa in September 1979. In February 1986, the unit was re-designated as 10th Area Support Group and served as the Installation Command for all Army units located on Okinawa. It was then officially reflagged effective 18 February 1986 as 10th Area Support Group (Provisional). The provisional status was dropped on 16 October 1987. During this timeframe, the headquarters was transferred to Torii Station. The 10th Area Support Group served as the installation command for all Army organization on Okinawa and provides contingency support to forces in the Pacific Rim.[58] U.S. Army Garrison Torii Station was activated on 11 July 2011 and was officially recognized as a battalion-level command. On 4 March 2014, U.S. Army Garrison Torii Station was redesignated U.S. Army Garrison Okinawa.

From 1972, IX Corps remained in the region conducting training and oversight to US Army forces in the area, and as such it was never deployed to support any other US Army contingencies. IX Corps remained a command component of United States Army Japan until 1994, when it was inactivated. At this point, the lineage of the corps was assumed by the 9th Theater Army Area Command, which was activated in its place.[9]

Lieutenant General James E. Moore was:

- Commanding General, IX Corps/Ryukyu Command/Deputy Governor, Ryukyu Islands, 1956–1957.

- Commanding General, IX Corps/U.S. Army Ryukyu Islands/Deputy Governor, Ryukyu Islands, 1957.

- Commanding General, IX Corps/U.S. Army Ryukyu Islands/U.S. High Commissioner, Ryukyu Islands, 1957–1958.

Lieutenant General Donald P. Booth was:

- Commanding General, IX Corps/U.S. Army Ryukyu Islands/U.S. High Commissioner, Ryukyu Islands, 1958–1961.

Lt. Gen. Albert Watson II was:

- Commanding General, U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, Aug 1964 – Oct 1966

Lt. Gen. Ferdinand T. Unger was:

- Commanding General, U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, O c t . 1966 – still in post Apr 1967 during GAO study on computers[59]

U.S. Army Ryukyu Islands (USARYIS) was active at least until from 22 April 1969 – 21 October 1970.

Honors

The IX Corps was awarded one campaign streamer for service in World War II, and nine campaign streamers and two unit decorations during its service in the Korean War for a total of ten streamers and two unit decorations in its operational history.[7]

Unit decorations

| Ribbon | Award | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1950 | for service in Korea | |

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1952–1953 | for service in Korea |

Campaign streamers

| Conflict | Streamer | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| World War II | Asiatic Pacific Theater | (No inscription) |

| Korean War | UN Offensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | CCF Intervention | 1950 |

| Korean War | First UN Counteroffensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | CCF Spring Offensive | 1951 |

| Korean War | UN Summer-Fall Offensive | 1951 |

| Korean War | Second Korean Winter | 1951–1952 |

| Korean War | Korea, Summer-Fall 1952 | 1952 |

| Korean War | Third Korean Winter | 1952–1953 |

| Korean War | Korea, Summer 1953 | 1953 |

References

Notes

- Varhola 2000, p. 278

- Dalessandro, Robert J.; Knapp, Michael G. (2008). Organization and Insignia of the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1923. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7643-2937-1.

- Organization and Insignia of the American Expeditionary Force

- Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War. Carlisle Barracks, PA: US Army War College. 1937. p. 163.

- Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, p. 343

- Barber, J. Frank (1922). History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, A. E. F. During the World War: 1917-1919. Lancaster, PA: Steinman & Steinman. pp. 7–8.

- "Lineage and Honors Information: IX Corps". United States Army Japan. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "The Institute of Heraldry: IX Corps". The Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- "IX Corps History". United States Army Reserve. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- "GlobalSecurity.org: IX Corps". GlobalSecurity. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- Marston 2005, p. 229

- Marston 2005, p. 236

- Marston 2005, p. 237

- Varhola 2000, p. 84

- Varhola 2000, p. 87

- Varhola 2000, p. 88

- Appleman 1998, p. 545

- Varhola 2000, p. 86

- Alexander 2003, p. 221

- Appleman 1998, p. 597

- Appleman 1998, p. 682

- Alexander 2003, p. 312

- Alexander 2003, p. 313

- Malkasian 2001, p. 31

- Varhola 2000, p. 14

- Malkasian 2001, p. 34

- Alexander 2003, p. 379

- Varhola 2000, p. 15

- Alexander 2003, p. 395

- Varhola 2000, p. 16

- Alexander 2003, p. 394

- Malkasian 2001, p. 39

- Alexander 2003, p. 400

- Varhola 2000, p. 17

- Varhola 2000, p. 18

- Varhola 2000, p. 19

- Malkasian 2001, p. 41

- Catchpole 2001, p. 120

- Malkasian 2001, p. 42

- Varhola 2000, p. 20

- Malkasian 2001, p. 44

- Alexander 2003, p. 403

- Malkasian 2001, p. 50

- Alexander 2003, p. 447

- Malkasian 2001, p. 53

- Varhola 2000, p. 25

- Varhola 2000, p. 26

- Malkasian 2001, p. 82

- Varhola 2000, p. 27

- Varhola 2000, p. 28

- Alexander 2003, p. 467

- Varhola 2000, p. 29

- Malkasian 2001, p. 52

- Malkasian 2001, p. 86

- Malkasian 2001, p. 87

- Varhola 2000, p. 31

- "U.S. ARMY GARRISON GETS NAME CHANGE... - U.S. Army Garrison Okinawa | Facebook". web.facebook.com. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Globalsecurity.org, 10 SG

- The Comptroller General of the United States (April 1967). "Report to the Congress of the United States - Review of the acquisition and installation of computers by the United States Army, Pacific" (PDF). gao.gov. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War We Lost, New York City, New York: Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, London, England: Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Malkasian, Carter (2001), The Korean War, Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-282-1

- Marston, Daniel (2005). The Pacific War Companion: from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ASIN B002ARY8KO.

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953. Mason City, Iowa: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4.