45th Infantry Division (United States)

The 45th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the United States Army, part of the Oklahoma Army National Guard, from 1920 to 1968. Headquartered mostly in Oklahoma City, the guardsmen fought in both World War II and the Korean War.

| 45th Division 45th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) 45th Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia. | |

| Active | 1923–1945 1946–1968 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | |

| Garrison/HQ | Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

| Nickname(s) | "Thunderbird"[1] |

| Motto(s) | Semper Anticus (Latin: "Always Forward")[2] |

| Engagements | World War II

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Troy H. Middleton William S. Key Dwight E. Beach Philip De Witt Ginder |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia (1920–46) |  |

| Distinctive unit insignia (1946–68) |  |

The 45th Infantry Division guardsmen saw no major action until they became one of the first National Guard units activated in World War II in 1941. They took part in intense fighting during the invasion of Sicily and the attack on Salerno in the 1943 Italian Campaign. Slowly advancing through Italy, they fought in Anzio and the Beachhead breakout to the capture of Rome. After landing in France during Operation Dragoon, they joined the 1945 drive into Germany that ended the War in Europe.

After brief inactivation and subsequent reorganization as a unit restricted to Oklahomans, the division returned to duty in 1951 for the Korean War. It joined the United Nations troops on the front lines during the stalemate of the second half of the war, with constant, low-level fighting and trench warfare against the People's Volunteer Army of China that produced little gain for either side. The division remained on the front lines in such engagements as Old Baldy Hill and Hill Eerie until the end of the war, returning to the U.S. in 1954.

The division remained a National Guard formation until its downsizing in 1968. Several units were activated to replace the division and carry on its lineage. Over the course of its history, the 45th Infantry Division sustained over 25,000 battle casualties, and its men were awarded ten Medals of Honor, twelve campaign streamers, the Croix de Guerre and the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation.

History

With the outbreak of World War I, troops of the National Guard were formed into the units which exist today, with the Colorado Guard forming the 157th Infantry Regiment, the Arizona Guard forming the 158th Infantry Regiment, and the New Mexico Guard forming the 120th Engineer Regiment. These units were attached to the 40th Infantry Division and deployed to France where they were used as "depot" forces to provide replacements for front-line units. They returned home at the end of the war.[3] The Oklahoma Guard units that would later become the 179th Infantry Regiment and 180th Infantry Regiment were assigned to the 36th Infantry Division and would earn a combat participation credit during the Meuse-Argonne Campaign in France as the 142nd Infantry.[4]

Inter-war years

|

1923–1940 "Square" Organization[5]

|

On 19 October 1920, units of the Oklahoma National Guard were organized as part the 45th Infantry Division, also manned with troops from Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico.[6] The division was formed and federally recognized as a National Guard unit on 3 August 1923 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.[7] It was assigned the 89th Infantry Brigade of the Colorado and Arizona National Guards, and the 90th Infantry Brigade of the Oklahoma National Guard.[8] As a consequence of these militia roots, when the division was properly organized, many of its members were marksmen and outdoorsmen from the remote frontier regions of the Southwestern United States.[9] The division's first commander was Major General Baird H. Markham.[10]

The 45th Infantry Division engaged in regular drills but no major events in its first few years, though the division's Colorado elements were called in to help quell a large coal mining strike.[11] The onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s severely curtailed its funding for training and equipment. Major General Roy Hoffman took command in 1931, followed by Alexander M. Tuthill, Alexander E. McPherren in 1935, and William S. Key in 1936.[10] In 1937, the division's troops were once again called up, this time to help manage a locust plague affecting Colorado.[11]

.svg.png.webp)

The division's original shoulder sleeve insignia, approved in August 1924,[12] featured a swastika, a common Native American symbol, as a tribute to the Southwestern United States region which had a large population of Native Americans. However, with the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, with its infamous swastika symbol, the 45th Division stopped using the insignia.[13] After a long process of reviewing design submissions, a design by Woody Big Bow, a Kiowa artist from Carnegie, Oklahoma, was chosen for the new shoulder sleeve insignia.[14] The new insignia featured the Thunderbird, another Native American symbol, and was approved in 1939.[1]

In August 1941, the 45th Infantry Division took part in the Louisiana Maneuvers, the largest peacetime exercises in U.S. military history.[15] The division was assigned to VIII Corps with the 2nd Infantry Division and the 36th Infantry Division, camped near Pitkin, Louisiana.[16] Still operating with outmoded equipment from World War I, the division did not perform well during these exercises.[17] With poor weather and bad equipment, the undertrained 45th Infantry Division was criticized by officers who considered it "feeble."[16] In spite of these deficiencies, less than one month later, the men were recalled to the active duty force, much to their chagrin, because of concerns of an impending American entry into World War II.[15]

World War II

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Naples-Foggia

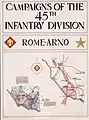

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Naples-Foggia Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Rome-Arno

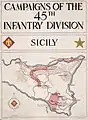

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Rome-Arno Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Sicily

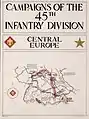

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Sicily Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Central Europe

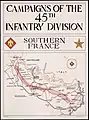

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Central Europe Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Southern France

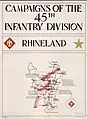

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Southern France Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Rhineland

Campaigns of the 45th Infantry Division: Rhineland

On 16 September 1940, the 45th Infantry Division, under Major General William S. Key, was federalized from state control into the regular army force.[7] It was one of four National Guard divisions to be federalized, alongside the 30th, the 41st and 44th Infantry Divisions, originally for a one-year period.[18] Its men immediately began basic combat training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.[19] Throughout 1942, it continued this training at Camp Barkeley, Texas,[20] before moving to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, to undergo amphibious assault training in preparation for an invasion of Italy.[21] It then moved to Pine Camp, New York briefly for winter warfare training, but was hampered by continuously poor weather. In January 1943 it moved to Fort Pickett, Virginia, for its final training.[22] The division, now commanded by Major General Troy H. Middleton, a Regular Army soldier and highly distinguished World War I veteran, moved to the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation's Camp Patrick Henry to await combat loading on the transports.[23]

The division's two combat commands, the 89th and 90th Infantry Brigades, were not activated, as the army favored smaller and more versatile regimental commands for the new conflict.[8] The 45th Infantry Division was instead based around the 157th, 179th, and 180th Infantry Regiments.[24] Also assigned to the division were the 158th, 160th, 171st, and 189th Field Artillery Battalions, the 45th Signal Company, the 700th Ordnance Company, the 45th Quartermaster Company, the 45th Reconnaissance Troop, the 120th Engineer Combat Battalion, and the 120th Medical Battalion.[24]

Sicily

|

1942–1945 "Triangular" Organization[25]

|

The 45th Division sailed from the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation for the Mediterranean region on 8 June 1943, combat loaded aboard thirteen attack transports and five cargo attack vessels as convoy UGF-9 headed by the communications ship USS Ancon.[21][23] By the time the 45th Division landed in North Africa on 22 June 1943, the Allies had largely secured the African theater. As a result, the division was not sent into combat upon arrival and instead commenced training at Arzew, French Morocco,[26] in preparation for the invasion of Sicily. Allied intelligence estimated that the island was defended by approximately 230,000 troops, the majority of which were drawn mostly from weak Italian formations and two German divisions which had been reconstituted after being destroyed earlier. Against this, the Allies planned to land 180,000 troops,[27] including the 45th Infantry Division, which was assigned to Lieutenant General Omar Bradley's II Corps, part of the U.S. Seventh Army under Lieutenant General George S. Patton, for the operation.[28]

The division was subsequently assigned a lead role in the amphibious assault on Sicily, coming ashore on 10 July.[29][30] Landing near Scoglitti, the southernmost U.S. objective on the island, the division advanced north on the U.S. force's eastern flank.[31] After initially encountering resistance from armor of the Herman Goering Division, the division advanced, supported by paratroopers of the 505th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, part of the 82nd Airborne Division, who landed inland on 11 July.[32] The paratroopers, conducting their first combat jump of the war, then set up to protect the 45th's flank against German counterattack, but without weapons to counter heavy armor, the paratroopers had to rely on support from the 2nd Armored Division to repulse the German Tiger I tanks.[32] As the division advanced towards its main objective to capture the airfields at Biscari, and Comiso, German forces pushed back.[33] For most of the first two weeks while the division moved slowly north, it encountered only light resistance from Italian forces fighting delaying actions.[34] Italian and German forces resisted fiercely at Motta Hill on 26 July, however, and for four days the 45th Division was held up there.[35] After this, the division was allocated to drive towards Messina, being ordered by the Seventh Army commander to cover the distance as quickly as possible.[36] The 45th Division spent a few days in that city, but on 1 August, the division was withdrawn from the front line for rest and rear-guard patrol duty,[26] after which the division was assigned to Major General Ernest J. Dawley's VI Corps, part of the U.S. Fifth Army, under Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, in preparation for the invasion of mainland Italy.[37]

Salerno

On 3 September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allied powers. Hoping to occupy as much of the country as humanly possible before the German Army could react, the U.S. Fifth Army prepared to attack Salerno.[38] On 10 September, elements of the division conducted its second landing at Agropoli and Paestum with the 36th Infantry Division, on the southernmost beaches of the attack.[37] Opposing them were elements of the German 29th Panzergrenadier Division and XVI Panzer Corps.[37] Against stiff resistance, the 45th pushed to the Calore River after a week of heavy fighting.[39] The Fifth Army was battered and pushed back by German forces until 20 September, when Allied forces were finally able to break out and establish a more secure beachhead.[37][40]

On 3 November it crossed the Volturno River and took Venafro.[39] The division had great difficulty moving across the rivers and through the mountainous terrain, and the advance was slow. After linking up with the British Eighth Army, which had advanced from the south, the combined force, under the 15th Army Group, commanded by British General Sir Harold Alexander, was stalled when it reached the Gustav Line.[41] Until 9 January 1944, the division, now under Major General William W. Eagles (replacing Major General Middleton who, struck down with arthritis, was sent to England to command VIII Corps in the Normandy invasion), inched forward into the mountains reaching St. Elia, north of Monte Cassino, before moving to a rest area.[39]

Anzio

Allied forces conducted a frontal assault on the Gustav Line stronghold at Monte Cassino, and VI Corps, under Major General John P. Lucas from 20 September, was assigned to Operation Shingle, detached from the 15th Army Group to land behind enemy lines at Anzio on 22 January 1944.[42] For this mission, CCA (Combat Command A) of the 1st Armored Division was attached to the 45th Infantry Division.[43] Landing on schedule, VI Corps surprised the Germans, but Major General Lucas's decision to consolidate the beachhead instead of attacking gave the Germans time to bring the LXXVI Panzer Corps forward to oppose the landings.[42][44]

One regiment of the 45th (the 179th Infantry) went ashore with the landings. In company with the British 1st Infantry Division, they advanced north along the Anzio-Albano road and captured the Aprilia "factory", but encountered ingrained resistance from German armored units a few miles further on. Lucas then ordered the rest of the division ashore. The 45th Division was deployed on the southeastern side of the beachhead, along the lower Mussolini Canal.[45]

On 30 January 1944, when VI Corps advanced from the beaches, it encountered heavy resistance and took heavy casualties.[42][46] VI Corps was stopped at the "Pimlott Line" (the perimeter of the beachhead), and the fight became a battle of attrition.

The first major German counterattack came in early February, was against the British 1st Division. Two regiments of the 45th (the 179th and 157th Infantry) were sent to the Aprilia sector to reinforce the British. The 179th Infantry and a tank battalion of CCA tried to recapture Aprilia but were repulsed. Lucas then moved the rest of the 45th Division to the left-center of the perimeter, at Aprilia and along the west branch of the Mussolini Canal.[45] For the next few months the 45th Infantry Division was mostly stuck in place, holding its ground during repeated German counterattacks, and subjected to bombardment from aircraft and artillery.[39]

On 16 February, a major German attack struck the 45th, and nearly broke through the 179th Infantry on 18 February. Lucas sent famed U.S. Army Ranger leader Colonel William Orlando Darby to assume command of the 157th Infantry, and the Germans were repulsed.[45] The next three months were spent on the defensive, with the 45th engaged in trench warfare, alike to that in World War I.

On 23 May, VI Corps, now commanded by Major General Lucian Truscott, went on the offensive, breaking out of the beachhead to the northeast, with the 45th Division forming the left half of the attack. By 31 May, the German defenses were shattered, and the 45th Division turned northwest, toward the Alban Hills and Rome.[47] On 4 June the 45th Division crossed the Tiber River below Rome, and entered the city along with other VI Corps troops.[48] Men of the 45th Division were the first Allied troops to reach the Vatican.

On 16 June, the 45th Division withdrew for rest in preparation for other operations.[39] At this time, VI Corps was attached to the Seventh Army, under Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, itself part of the 12th Army Group under Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers.[49] The 45th, 36th, and 3rd Infantry Divisions were pulled from the line in Italy in preparation for Operation Dragoon (formerly Anvil), the invasion of southern France. Dragoon was originally planned to coincide with the Normandy landings in the north, but was delayed until August because of a shortage of landing craft.[50]

France and Germany

The 45th Infantry Division participated in its fourth amphibious assault landing during Operation Dragoon on 15 August 1944, at St. Maxime, in Southern France.[39] The 45th Infantry Division landed its 157th and 180th regimental combat teams and captured the heights of the Chaines de Mar before meeting with the 1st Special Service Force.[51] The German Army, reeling from the Battle of Normandy, in which it had suffered a major defeat, pulled back after a short fight, part of an overall German withdrawal to the east following the landings.[52][53] Soldiers of the 45th Infantry Division engaged the dispersed forces of German Army Group G, suffering very few casualties.[48] The U.S. Seventh Army, along with Free French forces, were able to advance north quickly. By 12 September, the Seventh Army linked up with Lieutenant General George S. Patton's U.S. Third Army, advancing from Normandy, joining the two forces at Dijon.[50] Against slight opposition, it spearheaded the drive for the Belfort Gap. The 45th Infantry Division took the strongly defended city of Epinal on 24 September.[39] The division was then reassigned to V Corps, under the command of Major General Leonard T. Gerow, for its next advance.[49] On 30 September the division crossed the Moselle River and entered the western foothills of the Vosges, taking Rambervillers.[39] It would remain in the area for a month waiting for other units to catch up before crossing the Mortagne River on 23 October.[39] The division remained on the line with the U.S. 6th Army Group the southernmost of three army groups advancing through France.[54]

After the crossing was complete, the division was relieved from V Corps and assigned to Major General Wade H. Haislip's XV Corps.[49] The division was allowed a one-month rest, resuming its advance on 25 November, attacking the forts north of Mutzig. These forts had been designed by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1893 to block access to the plain of Alsace. The 45th Division next crossed the Zintzel River before pushing through the Maginot Line defenses.[39] During this time much of the division's artillery assets were attached to the 44th Infantry Division to provide additional support.[55] The 45th Infantry Division, now commanded by Major General Robert T. Frederick, who had previously commanded the 1st Special Service Force, was reassigned to VI Corps on New Year's Day.[49] From 2 January 1945, the division fought defensively along the German border, withdrawing to the Moder River.[39] It sent half of its artillery to support the 70th Infantry Division.[55] On 17 February the division was pulled off the line for rest and training. Once this rest period was complete, the division was assigned to XV Corps for the final push into German territory.[49] The 45th moved north to the Sarreguemines area and smashed through the Siegfried Line, on 17 March taking Homburg on the 21st and crossing the Rhine between Worms and Hamm on the 26th.[39] The advance continued, with Aschaffenburg falling on 3 April, and Nuremberg on the 20th.[39] The division crossed the Danube River on 27 April, and liberated 32,000 captives of the Dachau concentration camp on 29 April 1945.[39] The division captured Munich during the next two days, occupying the city until V-E Day and the surrender of Germany.[56] During the next month, the division remained in Munich and set up collection points and camps for the massive numbers of surrendering troops of the German armies. The number of POWs taken by the 45th Division during its almost two years of fighting totalled 124,840 men.[39] The division was then slated to move to the Pacific theater of operations to participate in the invasion of mainland Japan on the island of Honshu, but these plans were scrubbed before the division could depart after the surrender of Japan, on V-J Day.[57]

|

World War II Casualties |

Allegations of war crimes

During and after the war, courts-martial were convened to investigate possible war crimes by members of the division. In the first two cases, dubbed the Biscari massacre, American troops from C Company, 180th Infantry Regiment, were alleged to have shot 74 Italian and two German prisoners in Acate in July 1943 following the capture of an airfield in the area. George Patton, the Seventh Army commanding general, asked Omar Bradley, II Corps commanding general, to get the cases dismissed to prevent bad press, but Bradley refused. A non-commissioned officer later confessed to the crimes and was found guilty, but an officer who claimed he had only been following orders was acquitted.[59][60][61]

In a third incident, the Army considered court-martialling several officers of the 157th Infantry Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Felix L. Sparks after servicemen were accused of massacring German soldiers who were surrendering at the Dachau concentration camp in 1945. Some of the German troops were camp guards; the others were sick and wounded troops from a nearby hospital. The soldiers of the 45th Division who liberated the camp were outraged at the malnourishment and maltreatment of the 32,000 prisoners they liberated, some barely alive, and all victims of the Holocaust. After entering the camp, the soldiers found boxcars filled with dead bodies of prisoners who had succumbed to starvation or last-minute executions, and in rooms adjacent to gas chambers they found naked bodies piled from the floor to the ceiling.[62] The cremation ovens, which were still in operation when the soldiers arrived, contained bodies and skeletons as well. Some of the victims apparently had died only hours before the 45th Division entered the camp, while many others lay where they had died in states of decomposition that overwhelmed the soldiers' senses.[63] Accounts conflict over what happened and over how many German troops were killed. After investigating the incident, the Army considered court-martialling several officers involved, but Patton successfully intervened. The Seventh Army was being disbanded and Patton had been appointed Military Governor of Bavaria, placing the matter in his hands.[64] Some veterans of the 45th Infantry Division have said that only 30 to 50 German soldiers were killed and that very few were killed trying to surrender, while others have admitted to killing or refusing to treat wounded German guards.[65]

Confessed murderer Frank Sheeran later recalled his war service as the time when he first developed a callousness to the taking of human life. Sheeran claimed to have participated in numerous massacres and summary executions of German POWs, acts which violated the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the 1929 Geneva Convention on POWs. In later interviews with Charles Brandt, he divided such massacres into four categories:

- Revenge killings in the heat of battle. Sheeran told Brandt that, when a German soldier had just killed his close friends and then tried to surrender, he would often "send him to hell, too". He described often witnessing similar behavior by fellow GIs.[66]

- Orders from unit commanders during a mission. When describing his first murder for organized crime, Sheeran recalled: "It was just like when an officer would tell you to take a couple of German prisoners back behind the line and for you to 'hurry back'. You did what you had to do."[67]

- The Dachau massacre and other reprisal killings of concentration camp guards and trustee inmates.[68]

- Calculated attempts to dehumanize and degrade German POWs. While Sheeran's unit was climbing the Harz Mountains, they came upon a Wehrmacht mule train carrying food and drink up the mountainside. The female cooks were first allowed to leave unmolested, then Sheeran and his fellow GIs "ate what we wanted and soiled the rest with our waste". Then the Wehrmacht mule drivers were given shovels and ordered to "dig their own shallow graves". Sheeran later joked that they did so without complaint, likely hoping that he and his buddies would change their minds. But the mule drivers were shot and buried in the holes they had dug. Sheeran explained that by then, he "had no hesitation in doing what I had to do."[69]

After the war

|

During World War II, the 45th Division fought in 511 days of combat.[26] Nine soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor during their service with the 45th Infantry Division: Van T. Barfoot,[72] Ernest Childers,[73] Almond E. Fisher,[74] William J. Johnston,[75] Salvador J. Lara,[76] Jack C. Montgomery,[77] James D. Slaton,[73] Jack Treadwell,[78] and Edward G. Wilkin.[79] Soldiers of the division also received 61 Distinguished Service Crosses, three Distinguished Service Medals, 1,848 Silver Star Medals, 38 Legion of Merit medals, 59 Soldier's Medals, 5,744 Bronze Star Medals, and 52 Air Medals. The division received seven distinguished unit citations and eight campaign streamers during the conflict.[26]

Most of the division returned to New York in September 1945, and from there went to Camp Bowie, Texas. On 7 December 1945, the division was inactivated from the active duty force and its members reassigned to other Army units. The following year, on 10 September 1946, the 45th Infantry Division was reconstituted as a National Guard unit.[80] Instead of comprising units from several states, the post-war 45th was an all-Oklahoma organization.[81] During this time the division was also reorganized and as a part of this process the 157th Infantry was removed from the division's order of battle and replaced with the 279th Infantry Regiment.[82]

During this time, the U.S. Army underwent a drastic reduction in size. At the end of World War II, it contained 89 divisions, but by 1950, there were just 10 active divisions in the force, along with a few reserve divisions such as the 45th Infantry Division which were combat-ineffective.[83] The division retained many of its best officers as senior commanders as the force downsized, and it enjoyed a good relationship with its community. The 45th in this time was regarded as one of the better-trained National Guard divisions.[84] Regardless, by mid-1950 the division had only 8,413 troops, less than 45 percent[n 1] of its full-strength authorization.[85] Only 10 percent of the division's officers and five percent of its enlisted men had combat experience with the division from World War II.[86]

Korean War

At the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the U.S. Army looked to expand its force again to prepare for major conflict. After the North Korean People's Army invaded the Republic of Korea, four understrength U.S. divisions on occupation duty in Japan were rushed to South Korea to stand alongside the Republic of Korea Army. These were the 7th Infantry Division, the 1st Cavalry Division, the 24th Infantry Division, and the 25th Infantry Division, which were all under the control of the Eighth United States Army. Due to drastic reductions in U.S. military spending following the end of World War II, these divisions were equipped with worn-out or obsolete weaponry and suffered from a shortage of anti-armor weapons capable of penetrating the hulls of the North Korean T-34 tanks.[87][88]

Reinforcement pool

Initially, the division was used to provide a pool of reinforcements for the divisions which had been sent to the Korean War theater, and in January 1951 it provided 650 enlisted fillers for overseas service. Later that month, it was given 4,006 new recruits for its three infantry regiments and artillery assets, and each unit created a 14-week training program to prepare these new soldiers for combat.[89] Because of heavy casualties and slow reinforcement rates, the Army looked to the National Guard to provide additional units to relieve the beleaguered Eighth Army. At the time, the 45th Infantry Division was comprised overwhelmingly of high school students or recent graduates and only about 60 percent of its divisional troops had conducted training and drills with the division for a year or more. Additionally, only about 20 percent of its personnel had prior experience of military service from World War II.[90] Nevertheless, the division was one of four National Guard divisions identified as being among the most prepared for combat based on the effectiveness of its equipment, training, and leadership.[91] As a result, in February 1951, the 45th Infantry Division was alerted that it would sail for Japan.[92]

In preparation for the deployment, the division was sent to Fort Polk, Louisiana, to begin training and to fill its ranks.[93] After its basic training was complete, the division was sent to Japan in April 1951 for advanced training and to act as a reserve force for the Eighth United States Army, then fighting in Korea.[94] The involvement of the National Guard in the fighting in Korea was further expanded when the 40th Infantry Division of the California Army National Guard received warning orders for deployment as well.[95]

Initial struggles

On 1 September 1950,[96] the 45th Infantry Division was activated as the first National Guard division to be deployed to the Far East theater since World War II.[93][97] Nevertheless, it was not deployed to Korea until December 1951, when its advanced training was complete.[94][98] Following its arrival, the division moved to the front line to replace the 1st Cavalry Division, who were then delegated to the Far East reserve, having suffered over 16,000 casualties in less than 18 months of fighting.[99]

Though the 45th remained de facto segregated as an all-white unit in 1950,[100] individual unit commanders went to great lengths to integrate reinforcements from different areas and ethnicity into their units.[101] By 1952, it was fully integrated.[102] Additionally, in an effort to reduce the burden on the National Guard,[n 2] troops from the division were often replaced by enlisted and drafted soldiers from the active duty force. When it arrived in Korea, only half the division's manpower were National Guard troops, and over 4,500 guardsmen left between May and July 1952, continually replaced by more active duty troops, including an increasing number of African Americans.[103] Though the division was no longer an "All-Oklahoma" unit, leaders opted to keep its designation as the 45th Infantry Division.[104][n 3]

By the time the division was in place, the battle lines on both sides had largely solidified, leaving the 45th Infantry Division in a stationary position as it conducted attacks and counterattacks for the same ground.[105] The division was put under the command of Eighth Army's I Corps for most of the conflict.[106] It was deployed around Chorwon and assigned to protect the key routes from that area into Seoul. The terrain was difficult and the weather was poor in the region.[107] The division suffered its first casualty on 11 December 1951.[108]

Initially, the division did not fare well, though it improved quickly.[94] Its anti-aircraft and armor assets were used as mobile artillery, which continuously pounded Chinese positions. The 45th, in turn, was under constant artillery and mortar attack.[109] It also conducted constant small-unit patrols along the border seeking to engage Chinese outposts or patrols. These small-unit actions made up the majority of the division's combat in Korea.[110] Chinese troops were well dug-in and better trained than the troops of the inexperienced 45th, and it suffered casualties and frequently had to disengage when it was attacked.[111]

In the division's first few months on the line, Chinese forces conducted three raids in its sector. In retaliation, the 245th Tank Battalion sent nine tanks to raid Agok.[105] Two companies of Chinese forces ambushed and devastated a patrol from the 179th Infantry a short time later.[105] In the spring, the division launched Operation Counter, which was an effort to establish 11 patrol bases around Old Baldy Hill. The division then defended the hill against a series of Chinese assaults from the Chinese 38th Army.[105]

Final engagements and the end of the war

The 45th Infantry Division, along with the 7th Infantry Division, fought off repeated Chinese attacks all along the front line throughout 1952, and Chinese forces frequently attacked Old Baldy Hill into the fall of that year.[112] Around that time, the 45th Infantry Division relinquished command of Old Baldy Hill to the 2nd Infantry Division. Almost immediately the Chinese launched a concentrated attack on the hill, overrunning the U.S. forces.[113] Heavy rainstorms prevented the divisions from retaking the hill for around a month, and when it was finally retaken it was heavily fortified to prevent further attacks.[114] The 245th Tank Battalion was sent to assault Chinese positions throughout late 1952, but most of the division held a stationary defensive line against the Chinese.[112]

In early 1953, North Korean forces launched a large-scale attack against Hill 812, which was then under the control of K Company, 3rd Battalion, 179th Infantry.[115] The ensuing Battle of Hill Eerie was one of a series of larger attacks by Chinese and North Korean forces which produced heavier fighting than the previous year had seen. These offensives were conducted largely in order to secure a better position during the ongoing truce negotiations.[115] Chinese forces continued to mount concentrated attacks on the lines of the UN forces, including the 45th Infantry Division, but the division managed to hold most of its ground, remaining stationary until the end of the war in the summer of 1953.[116]

During the Korean War the 45th Infantry Division suffered 4,004 casualties, consisting of 834 killed in action and 3,170 wounded in action.[94] The division was awarded four campaign streamers and one Presidential Unit Citation.[117] One soldier from the division, Charles George, was awarded the Medal of Honor while serving in Korea.[118]

After Korea

The division briefly patrolled the Korean Demilitarized Zone following the signing of the armistice ending the war, but most of its men returned home and reverted to National Guard status on 30 April 1954.[80] Its colors were returned to Oklahoma on 25 September of that year, formally ending the division's presence in Korea.[104]

The division remained as a unit of the Oklahoma National Guard, and participated in no major actions throughout the rest of the 1950s save regular weekend and summer training exercises. In 1963, the formation was reorganized in accordance with the Reorganization Objective Army Divisions plan, which saw the establishment of a 1st, 2nd and 3rd Brigade within the division. These brigades would see no major deployments or events, and were inactivated five years later in 1968.[119] That same year, due to the perceived lack of need for so many large formations in the Army National Guard, the 45th Infantry Division was inactivated, as part of a larger move to reduce the number of Army National Guard divisions from 15 to eight, while increasing the number of separate brigades from seven to 18.[120] In its place, the independent 45th Infantry Brigade (Separate) was established.[80][121] The 45th Infantry Brigade received all of the 45th Division's lineage and heraldry, including its shoulder sleeve insignia.[2] Also activated from division assets were the 45th Field Artillery Group, later redesignated the 45th Fires Brigade, and the 90th Troop Command.[122][123]

Honors

The 45th Infantry Division was awarded eight campaign streamers and one foreign unit award in World War II and four campaign streamers and one foreign unit award in the Korean War, for a total of twelve campaign streamers and two foreign unit decorations in its operational history.[7]

| Conflict | Streamer | Inscription | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| French Croix de Guerre, World War II (With Palm) | Embroidered "Acquafondata" | 1944 | |

| European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Streamer | Sicily (with Arrowhead) | 1943 | |

| Naples–Foggia (with Arrowhead) | 1943 | ||

| Anzio (with Arrowhead) | 1943 | ||

| Rome–Arno | 1944 | ||

| Southern France (with Arrowhead) | 1944 | ||

| Rhineland | 1944–45 | ||

| Central Europe | 1945 | ||

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | For service in Korea | 1952–53 | |

| Korean Service Campaign Streamer | Second Korean Winter | 1951–52 | |

| Korea, Summer–Fall 1952 | 1952 | ||

| Third Korean Winter | 1952–53 | ||

| Korea, Summer 1953 | 1953 |

Museum

The 45th Infantry Division Museum is located in Oklahoma City, and includes a substantial collection of cartoons by World War II cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who served with it during the war.[124]

Commanding Generals

| MG | Baird H. Markham | 15 Feb 1923 | 6 Apr 1931 |

| MG | Roy V. Hoffman | 13 Jun 1931 | 13 Jun 1933 |

| MG | Alexander M. Tuthill | 14 Jun 1933 | 21 Oct 1935 |

| MG | Charles E. McPherren | 25 Nov 1935 | 29 Jul 1936 |

| MG | William S. Key | 29 Jul 1936 | 13 Oct 1942 |

| MG | Troy H. Middleton | 14 Oct 1942 | 21 Nov 1943 |

| MG | William W. Eagles | 22 Nov 1943 | 2 Dec 1944 |

| MG | Robert T. Frederick | 3 Dec 1944 | 20 Sep 1945 |

| BG | Paul D. Adams | 21 Sep 1945 | 25 Oct 1945 |

| BG | H.J.D. Meyer | 26 Oct 1945 | 7 Dec 1945 |

| MG | James C. Styron | 5 Sep 1946 | 20 May 1952 |

| MG | David Ruffner | 21 May 1952 | 15 Mar 1953 |

| MG | Philip De Witt Ginder | 16 Mar 1953 | 30 Nov 1953 |

| MG | Paul D. Harkins | 1 Dec 1953 | 15 Mar 1954 |

| BG | Harvey H. Fischer | 18 Mar 1954 | 27 Apr 1954 |

| MG | Hal L. Muldrow, Jr | 10 Sep 1952 | 31 Aug 1960 |

| MG | Frederick Alvin Daugherty | 1 Sep 1960 | 20 Nov 1964 |

| MG | Jasper N. Baker | 21 Nov 1964 | 31 Jan 1968 |

Note: Similarity of dates for General Muldrow and commanders beginning with General Ruffner is because 45th Infantry Division, AUS, was retained in Korea while twin unit, 45th Infantry Division, NGUS, was activated in Oklahoma.[125]

References

Notes

- As of 1 August 1950, the division consisted of 698 commissioned officers, 64 warrant officers, and 7,651 enlisted men. Army doctrine dictated a fully manned infantry division at 910 officers, 132 warrant officers, and 17,460 enlisted men. The National Guard at the time was operating at a reduced authorization of 851 officers, 130 enlisted men, and 12,777 enlisted men. See Donnelly 2001, p. 92.

- Fearing political ramifications, Army leaders sought to prevent large numbers of casualties from any one state, and the 45th Infantry Division was an all-Oklahoma organization at the beginning of the war. See: Donnelly 2001, p. 122

- As a result of this effort, two 45th Infantry Division units existed between 1952 and 1953; the mostly Active-duty 45th Infantry Division (AUS) in Korea, and the National Guard 45th Infantry Division (NGUS) in Oklahoma. In practice, the military institutionally recognized the Korea unit as the only "official" division, and most of the returning Oklahoma guardsmen were either separated from the Guard at the end of their enlistments or remained in inactive reserve status. See: Donnelly 2001, p. 122

Citations

- Whitlock 2005, p. 21

- The Institute of Heraldry: 45th Infantry Brigade, Fort Belvoir, Virginia: The Institute of Heraldry, archived from the original on 30 September 2012, retrieved 12 June 2012

- Whitlock 2005, p. 17

- "142nd Infantry Regiment". Texas Military Forces Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Stanton 1945, p. 126

- McGrath 2004, p. 234

- Wilson 1999, p. 663

- McGrath 2004, p. 171

- Whitlock 2005, p. 11

- Whitlock 2005, p. 18

- Whitlock 2005, p. 19

- Whitlock 2005, p. 20

- Stout & Yeide 2007, p. 18

- Perry 2009, p. 115

- Whitlock 2005, p. 5

- Whitlock 2005, p. 9

- Whitlock 2005, p. 7

- Whitlock 2005, p. 6

- Whitlock 2005, p. 10

- Whitlock 2005, pp. 22–28

- Blumenson 1999, p. 33

- Whitlock 2005, p. 29

- Bykofsky & Larson 1990, p. 194

- Young 1959, p. 592

- Stanton 1945, p. 179

- Young 1959, p. 544

- Collier 2003, p. 56

- Collier 2003, p. 23

- Muir 2001, p. 182

- Axelrod 2006, p. 104

- Collier 2003, p. 22

- Muir 2001, p. 184

- Axelrod 2006, p. 105

- Garland & Smyth 1965, p. 206

- Garland & Smyth 1965, p. 127

- Axelrod 2006, p. 107

- Pimlott 1995, p. 140

- Blumenson 1999, p. 12

- Young 1959, p. 545

- Collier 2003, p. 57

- Pimlott 1995, p. 141

- Pimlott 1995, p. 142

- Clark 2007, p. 78

- Collier 2003, p. 58

- "Anzio1944". The U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- Collier 2003, p. 124

- "Rome–Arno 1944". The U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- Collier 2003, p. 60

- Stanton 1945, p. 184

- Pimlott 1995, p. 166

- Stout & Yeide 2007, p. 29

- Pimlott 1995, p. 167

- Stout & Yeide 2007, p. 30

- Pimlott 1995, p. 189

- Stanton 1945, p. 183

- Kennedy 2003, p. 426

- Kennedy 2003, p. 427

- Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- Atkinson 2007, p. 119

- Botting & Sayer 1989, pp. 354–359

- Whitlock 2005, p. 389

- Whitlock 2005, pp. 360–364

- Whitlock 2005, p. 359

- Sparks, Felix. "Liberation of Dachau". Albert R. Panebianco's World War II Website. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Whitlock 2005, pp. 365–366

- Brandt (2004), p. 50.

- Brandt (2004), p. 84.

- Brandt (2004), p. 52.

- Brandt (2004), p. 51.

- "Lt. Kleindienst's Forward Observer's Notebook". Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Codes Used in the Daily Journals of the Command Reports". Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Whitlock 2005, p. 292

- Whitlock 2005, p. 103

- Whitlock 2005, p. 323

- Whitlock 2005, p. 229

- Santschi, Darrell R. (23 February 2014). "Riverside men to get top honor: Jesus S. Duran and Salvador J. Lara will be awarded the Medal of Honor". The Press-Enterprise.

- Whitlock 2005, p. 245

- Whitlock 2005, p. 343

- Whitlock 2005, p. 345

- Wilson 1999, p. 665

- Donnelly 2001, p. 25

- Donnelly 2001, p. 230

- Stewart 2005, p. 211

- Donnelly 2001, p. 91

- Donnelly 2001, p. 92

- Donnelly 2001, p. 90

- Stewart 2005, p. 222

- Catchpole 2001, p. 41

- Donnelly 2001, p. 61

- Donnelly 2001, p. 27

- Donnelly 2001, p. 26

- Donnelly 2001, p. 62

- Varhola 2000, p. 101

- Varhola 2000, p. 102

- Varhola 2000, p. 100

- Wilson, John B. (1999). CMH Publication 60-7 "Armies, Corps, Divisions, and Separate Brigades" (1999 ed.). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 664. ISBN 0-16-049994-1.

- Donnelly 2001, p. 98

- Donnelly 2001, p. 102

- Varhola 2000, p. 93

- Donnelly 2001, p. 49

- Donnelly 2001, p. 50

- Donnelly 2001, p. 121

- Donnelly 2001, p. 120

- Donnelly 2001, p. 122

- Varhola 2000, p. 24

- Varhola 2000, p. 86

- Donnelly 2001, p. 105

- Ecker 2004, p. 130

- Donnelly 2001, p. 160

- Donnelly 2001, p. 107

- Donnelly 2001, p. 108

- Varhola 2000, p. 25

- Catchpole 2001, p. 168

- Catchpole 2001, p. 169

- Varhola 2000, p. 28

- Varhola 2000, p. 30

- Wilson 1999, p. 666

- Ecker 2004, p. 160

- McGrath 2004, p. 202

- Wilson 2001, p. 338

- Wilson 2001, p. 240

- Talley, Tim. "Legislature Honors 45th Infantry Brigade". Durant Democrat. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Home at Last – National Guardsmen Return Home". Tulsa Beacon. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Bill Mauldin Cartoon Collection". 45thdivisionmuseum.com. 45th Infantry Division Museum. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Nelson, Guy (1970). Thunderbird: A History of the 45th Infantry Division. Oklahoma City, OK: 45th Infantry Division Association. pp. 130–131.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 45th Infantry Division. |

- Atkinson, Rick (2007), The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944 (The Liberation Trilogy), New York City, New York: Henry Holt and Co., ISBN 0-8050-6289-0

- Axelrod, Alan (2006), Patton: A Biography, London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1403971395

- Blumenson, Martin (1999), United States Army in World War II: Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001884-8

- Botting, Douglas; Sayer, Ian (1989), Hitler's Last General: The Case Against Wilhelm Mohnke, London, United Kingdom: Bantam Books, ISBN 0-593-01709-9

- Bykofsky, Joseph; Larson, Harold (1990), The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas, United States Army in World War II, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, LCCN 56060000

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, London, United Kingdom: Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Clark, Lloyd (2007), Anzio: Italy and the Battle for Rome – 1944, New York City, New York: Grove Press, ISBN 978-0-8021-4326-6

- Collier, Paul (2003), Second World War: Volume 4 The Mediterranean 1940–1945, London, United Kingdom: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-96848-5

- Donnelly, William (2001), Under Army Orders: The Army National Guard During The Korean War, College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 978-1-58544-117-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0786419807

- Garland, Howard N.; Smyth, Albert N. (1965), United States Army in World War II: The Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, OCLC 396186

- Kennedy, David M. (2003), The American People in World War II: Freedom from Fear, Part Two, Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516893-8

- McGrath, John J. (2004), The Brigade: A History: Its Organization and Employment in the U.S. Army, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-4404-4915-4

- Muir, Malcolm Jr. (2001), The Human Tradition in the World War II Era, Lanham, Maryland: SR Books, ISBN 978-0-8420-2786-1

- Nelson, Guy (1970), Thunderbird: A History of the 45th Infantry Division, Oklahoma City, OK: 45th Infantry Division Association

- Perry, Robert (2009), Uprising!: Woody Crumbo's Indian Art, Ada, Oklahoma: Chickasaw Press, ISBN 978-0979785856

- Pimlott, John (1995), The Historical Atlas of World War II, New York City, New York: Henry Holt and Company, ISBN 978-0-8050-3929-0

- Stanton, Shelby (1945), Order of Battle of the United States Army: World War II European Theater of Operations, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001967-8

- Stewart, Richard W. (2005), American Military History Volume II: The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917–2003, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-072541-8

- Stout, Mark; Yeide, Harry (2007), First to the Rhine: The 6th Army Group in World War II, New York City, New York: Zenith Press, ISBN 978-0-76-033146-0

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Mason City, Iowa: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

- Whitlock, Flint (2005), The Rock of Anzio: From Sicily To Dachau, A History of the U.S. 45th Infantry Division, New York City, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-813343-01-3

- Wilson, John B. (1999), Armies, Corps, Divisions, and Separate Brigades, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-160499-94-4

- Wilson, John B. (2001), Maneuver and Firepower: Divisions and Separate Brigades, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-0-89875-498-8

- Young, Gordon Russell (1959), Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States, Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, ISBN 978-0758135483

- Rothberg, Daniel (21 February 2014). "Obama will award Medal of Honor to 24 overlooked Army veterans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 December 2017.