Iapygians

The Iapygians or Apulians (Greek: Ἰάπυγες, Ĭāpyges; Latin: Iapyges, Iapygii) were an Indo-European people, dwelling in an eponymous region of the southeastern Italian Peninsula named Iapygia (modern Apulia) between the beginning of the first millennium BC and the first century BC. They were divided into three tribes: the Daunians, Peucetians and Messapians. After their lands were gradually colonized by the Romans from the late 4th century onward and eventually annexed to the Roman Republic by the early 1st century BC, Iapygians were fully Latinized and assimilated into Roman culture.

Name

The region was known to the Greeks of the 5th century BC as Iapygía ('Ιαπυγία), and its inhabitants as the Iápyges ('Ιάπυγες). It was probably the term used by the indigenous peoples to designate themselves.[1] The name Iapyges has also been compared to that of the Iapydes, an Illyrian tribe of northern Dalmatia.[2]

Some ancient sources treat Iapygians and Messapians as synonymous, and several writers of the Roman period referred to them as Apuli in the north, Poediculi in the centre, and Sallentini or Calabri in the south. Those discrepancies in the exonyms may indicate that the sub-ethnic Iapygian structures were unstable and sometimes fragmented. By the middle of the third century, Iapygians were generally divided by contemporary observers among three peoples – the Daunians in the north, the Peucetians in the centre, and the Messapians in the south.[1]

The name of the modern Italian region of Apulia stems from Iapygia after passing from Greek to Oscan to Latin and undergoing morphological changes (Iapudia, Apudia, then modern Puglia).[1]

Geography

Iapygia (modern-day Apulia) was located in the southeastern part of the Italian Peninsula, between the Appennine Mountains and the Adriatic Sea.[3]

The northeast area of the region, dominated by the massif of Monte Gargano (1,055 m), was largely unsuited for agriculture and abandoned to forests.[3] To the south and west of the Gargano stretched the largest plain of peninsular Italy, the Tavoliere delle Puglie. Although it mainly consists of sands and gravels, the plain is also crossed by several rivers. In ancient times, the land was best suited for cereal cultivation and, above all, for the pasturage of sheep in the winter. The Ofanto river, one of the longest rivers of the Italian Peninsula, marked the southern border of the plain.[3] Despite their name, the impervious Daunian Mountains (1,152 m), west of the plain, were strongly hold by the Hirpini, an Oscan-speaking Samnite tribe.[4]

Central Iapygia was composed of the Murge Plateau (686 m), an area poor in river. The western half of the massif was suitable only for grazing sheep; nearer the sea, the land was more adapted to cultivation, and likely used in ancient times to produce grains.[5]

In the Salento peninsula, the landscape was more varied, though still without river formation. Olives are known to have been cultivated in this area during the pre-Roman period, but the scale of the production is uncertain.[5] Several Greek colonies were located on the coast of the Gulf of Taranto, nearby the indigenous Messapians in southern Iapygia, most notably Taras, founded in the late 8th century BC, and Metapontion, founded in the late 7th century.[5]

Culture

Language

The Iapygians were a "relatively homogeneous linguistic community" speaking a non-Italic, Indo-European language, commonly called 'Messapic'. The language, written in variants of the Greek alphabet, is attested from the mid-6th to the late-2nd century BC.[6] Some scholars have argued that the term 'Iapygian languages' should be preferred to refer to those dialects, and the term 'Messapic' reserved to the inscriptions found in the Salento peninsula, where the specific Messapian people dwelt in the pre-Roman era.[6]

During the 6th century BC, Messapia, and more marginally Peucetia, underwent Hellenizing cultural influences, mainly from the nearby Taras. The use of writing systems was introduced in this period, with the acquisition of the Laconian-Tarantine alphabet and its adaptation to the Messapic language.[7][8] The second great Hellenizing wave occurred during the 4th century BC, this time also involving Daunia and marking the beginning of Peucetian and Daunian epigraphic records, in a local variant of the Hellenistic alphabet that replaced the older Messapic script.[7][9][10]

By the 4th century BC, inscriptions from central Iapygia suggest that the local artisan class had acquired some proficiency in the Greek language,[11] while the whole regional elite was used to learning Latin by the 3rd century BC. The Oscan language became also widespread after Italic peoples had occupied the territory in that period.[12] Along with the Messapic dialects, Greek, Oscan and Latin were consequently spoken and written all together in the whole region of Iapygia during the Romanization period,[13] and bilingualism in Greek and Messapic was probably common in the Salento peninsula.[14]

Religion

The late pre-Roman religion of Iapygians appears as a substrate of indigenous beliefs mixed with Greek elements.[2] The Roman conquest probably accelerated the hellenisation of a region already influenced by contacts with Magna Grecia from the 8th century BC onward.[15] Aphrodite and Athena were thus worshipped in Iapygia as Aprodita and Athana, respectively.[16] Some deities of native origin have also been highlighted by scholars, such as Zis ('sky-god'), Menzanas ('lord of horses'), Venas ('desire'), Taotor ('the people, community'), and perhaps Damatura ('mother-earth').[17]

Pre-Roman religious cults have also left few material traces.[18] Preserved evidence indicate that indigenous Iapygian beliefs featured the sacrifices of living horses to the god Menzanas, the fulfilling of oracles for anyone who slept wrapped in the skin of a sacrificed ewe, and the curative powers of the waters at the herõon of the god Podalirius, preserved in Greek tales.[2][19][20] Several cave sanctuaries have been identified on the coast, most notably the Grotta Porcinara sanctuary (Santa Maria di Leuca), in which both Messapian and Greek marines used to write their vows on the walls.[18]

It is likely that Peucetians had no civic cult requiring public buildings, and if urban sanctuaries have been identified in Daunia (at Teanum Apulum, Lavello, or Canosa), no conspicuous buildings are found before the Romanization period.[18]

Dress

The Iapygian peoples are noted for their ornamental dress.[1] By the 7th century BC, the Daunian aristocracy wore highly ornate costume and much jewellery, a custom that has persisted in the classical period, with depictions of Iapygians with long hair, wearing highly patterned short tunics with elaborate fringes. Young women were portrayed with long tunics belted at the waist, generally with a head-band or diadem.[1] On ritual or ceremonial occasions, the women of central Iapygia wore a distinctive form of mantle over their heads that left the headband visible above the brow.[21]

Burial

Iapygian funeral traditions were distinct from that of neighbouring Italic peoples: whereas the latter banished adult burials to the fringes of their settlements, the inhabitants of Iapygia buried their dead both outside and inside their own settlements.[22][21] Although females may sometimes have been buried with weapons, arms, and armour, such a custom was normally reserved to male funerals.[23]

Until the end of the 4th century BC, the normal practice among Daunians and Peucetians was to lay out the body in a fetal position with the legs drawn up towards the chest, perhaps symbolizing the rebirth of the soul in the womb of Mother Earth.[18] Messapians, by contrast, laid out their dead in the extended position as did other Italic peoples. From the 3rd century BC, extended burials with the body lying on its back began to appear in Daunia and Peucetia, although the previous custom survived well into the 2nd century BC in some areas.[18]

History

_(simple_map).svg.png.webp)

Origin

The leading view among scholars, already mentioned by ancient sources and supported by archaeological evidence, is that Iapygians have migrated from the Western Balkans towards southeastern Italy in the early first millennium BCE.[24][note 1]

Pre-Roman period

The Iapygians most likely left the eastern coasts of the Adriatic for Italy from the 11th century BC onwards,[25] merging with pre-existing Italic and Mycenean cultures and providing a decisive cultural and linguistic imprint.[7] The three main Iapygian tribal groups–Daunians, Peucetians and Messapians–retained a remarkable cultural unity in the first phase of their development. After the 8th century BC, however, they began a phase marked by a process of differentiation due to internal and external causes.[7]

Contacts between Messapians and Greeks intensified after the end of the 8th century BC and the foundation of the Spartan colony of Taras, preceded by earlier precolonial Mycenaean incursions during which the site of Taras seems to have already played an important role.[2] Until the end of the 7th century, however, Iapygia was generally not encompassed in the area of influence of Greek colonial territories, and with the exception of Taras, the inhabitants were evidently able to avoid other Greek colonies in the region.[7][26] During the 6th century BC Messapia, and more marginally Peucetia, underwent Hellenizing cultural influences, mainly from the nearby Taras.[7]

The relationship between Messapians and Tarantines deteriorated over time, resulting in a series of clashes between the two peoples from the beginning of the 5th century BC.[7] After two victories of the Tarentines, the Iapygians inflicted a decisive defeat on them, causing the fall of the aristocratic government and the implementation of a democratic one in Taras. It also froze relations between Greeks and the indigenous people for about half a century. Only in the late-5th and 6th centuries did they re-establish relationships. The second great Hellenizing wave occurred during the 4th century BC, this time also involving Daunia.[7]

Punic Wars

The Iapygians are mentioned by Polybius as having provided Socii troops for Rome's armies in the wars against Carthage.

Roman conquest

The Roman conquest of Iapygia started in the late 4th century, with the subjugation of the Canusini and the Teanenses.[27] It paved the way for Roman hegemony in the entire peninsula, as they used their progression in the region to contain Samnite power and encircle their territory during the Samnite Wars.[28] By the early third century, Rome had planted two strategic colonies, Luceria (314) and Venusia (291), on the border of Iapygia and Samnium.[29]

Social organization

In the early period, the Iapygian housing system was made up of small groups of huts scattered throughout the territory, different from the later Greco-Roman tradition of cities. The inhabitants of the rural districts gathered for common decisions, for feasts, for religious practices and rites, and to defend themselves against external attacks.[7]

From the 6th century BC onward, the large but thinly occupied settlements that had been founded around the beginning of the first millennium BC began to take on a more structured form.[30] The largest of them gradually gained the administrative capacity and the manpower to erect stone defensive walls and eventually to mint their own coins, indicating both urbanization and the assertion of political autonomy.[31][30]

According to Thucydides, some of these Iapygian communities were ruled by powerful individuals in the late 5th century BC.[32] A small number of them had grown into such large fortified settlements that they probably regarded themselves as autonomous city-states by the end of the 4th century,[33][34] and some of the northern cities were seemingly in control of an extensive territory during that period.[33] Arpi, who had the largest earthen ramparts of Iapygia in the Iron Age, and Canusium, whose territory probably straddled the Ofanto River from the coast up to Venusia, appear to have grown into regional hegemonic powers.[35]

This regional hierarchy of urban power, in which a few dominant city-states competed with each other in order to assert their own hegemony over limited resources, most likely led to frequent internecine warfare between the various Iapygian groups, and to external conflicts between them and foreign communities.[33]

Warfare

As evidenced by items found in graves and warriors shown on red-figure vase paintings, Iapigyan fought with little else defensive armour than a shield, sometimes a leather helmet and a jerkin, exceptionally a breastplate.[36] Their most frequent weapon was the thrusting spear, followed by the javelin, whereas swords were relatively rare. Bronze belts were also a common item found in warrior graves.[36]

Scenes of combat depicted on red-figure vase paintings also demonstrate that the various Iapygian communities were frequently involved in conflict with each other, and that prisoners of war were taken for ransom or to be sold into slavery.[36]

Economy

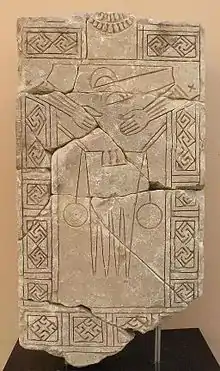

Archaeological evidence suggest that transhumance was practiced in pre-Roman Iapygia during the first millennium BC, and that wide areas of the region were reserved to provide pasture for transhumant sheep.[37] Weaving was indeed an important activity in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. The textile made from wool was most likely marketed in the Greek colony of Taranto, and the winter destination of Iapygian pastoralists probably located in the Tavoliere plain, where the weaving industry was already well developed by the seventh or early sixth century BC, as evidenced by the depiction of weavers at work on a stelae.[37]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illyria & Illyrians. |

Notes

- Boardman & Sollberger 1982, p. 231: "Apart from the spears and spear-heads of 'South-Illyrian' type (...), a connexion can be traced between Albania and Italy through various features in the pottery (shapes, handles; later on also painted geometric decoration); for although in Albania they derive from an earlier local tradition, they seem to represent new elements in Italy. In the same way we can account for the fibulae – typically Illyrian – arching in a simple curve with or without buttons, which one finds in southern Italy and in Sicily, and also some in which the curve is decorated with 'herring-bone' incisions, like examples from the eastern coast of the Adriatic. These influences appear finally in the rites of burial in tumuli in the contracted position, which are seen at this period in southern Italy, especially in Apulia. There is also evidence, as we have seen elsewhere, for supposing that in the diffusion of these Illyrian influences in Italy the Illyrian tribes which were displaced at the beginning of this period from the South-Eastern sea-board of the Adriatic and passed over into Italy may have played a significant role."; Wilkes 1992, p. 68: "...the Messapian language recorded on more than 300 inscriptions is in some respects similar to Balkan Illyrian. This link is also reflected in the material culture of both shores of the southern Adriatic. Archaeologists have concluded that there was a phase of Illyrian migration into Italy early in the first millennium BC."; Fortson 2004, p. 407: "They are linked by ancient historians with Illyria, across the Adriatic sea; the linkage is borne out archeologically by similarities between Illyrian and Messapic metalwork and ceramics, and by personal names that appear in both locations. For this reason, the Messapic language has often been connected by modern scholars to Illyrian; but, as noted above, we have too little Illyrian to be able to test this claim."

References

- Small 2014, p. 18.

- Pallottino 1992, p. 50.

- Small 2014, p. 13.

- E. T. Salmon (1989). "The Hirpini: "ex Italia semper aliquid novi"". Phoenix. 43 (3): 225–235. doi:10.2307/1088459. JSTOR 1088459.

- Small 2014, p. 14.

- De Simone 2017, pp. 1839–1840.

- Salvemini & Massafra 2005, pp. 7–16.

- De Simone 2017, p. 1840.

- Marchesini 2009, pp. 139–141.

- De Simone 2017, p. 1841.

- Small 2014, p. 32.

- McInerney 2014, p. 121.

- Salvemini & Massafra 2005, pp. 17–29.

- Adams 2003, pp. 116–117.

- Fronda 2006, pp. 409–410.

- Krahe 1946, p. 199–200.

- Krahe 1946, p. 204; Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 274, Gruen 2005, p. 279; West 2007, pp. 166, 176; De Simone 2017, p. 1843; Lamboley 2000, p. 130

- Small 2014, p. 20.

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 274.

- Lamboley 2000, p. 138 (note 34): Festus, De verborum significatu (frg. p. 190 ed. Lindsay) : Et Sallentini, apud quos Menzanae Iovi dicatus uiuos conicitur in ignem [En témoignent aussi les Sallentins qui jettent vivant dans les flammes un cheval consacré à Jupiter Menzanas].

- Small 2014, p. 19.

- Pallottino 1992, p. 51.

- Small 2014, p. 27.

- Boardman & Sollberger 1982, pp. 839–840; Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 278; Salvemini & Massafra 2005, pp. 7–16; Matzinger 2017, p. 1790

- Boardman & Sollberger 1982, p. 229, 231.

- Graham 1982, pp. 112–113.

- Fronda 2006, p. 399.

- Fronda 2006, p. 397: "Rome's control of Apulia would prove vital during Rome's conflicts with the Samnites since the Romans used Apulia as a staging area to attack Samnium's eastern flank."; p. 417: "Therefore, Roman actions in Apulia in 318/317 may have formed part of a long-term strategy of encircling Samnium, or at least a policy of securing allies so that Rome was better positioned to confront and subdue the Samnites..."

- Fronda 2006, p. 397.

- Small 2014, pp. 20–21.

- Fronda 2006, p. 409.

- Small 2014, p. 23.

- Fronda 2006, p. 411.

- Small 2014, p. 22.

- Fronda 2006, p. 410.

- Small 2014, p. 28.

- Small 2014, p. 16.

Bibliography

- Adams, James N. (2003). Bilingualism and the Latin Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81771-4.

- Boardman, John; Sollberger, E. (1982). J. Boardman; I. E. S. Edwards; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. III (part 1) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521224969.

- De Simone, Carlo (2017). "Messapic". In Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. 3. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-054243-1.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7.

- Fronda, Michael P. (2006). "Livy 9.20 and Early Roman Imperialism in Apulia". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 55 (4): 397–417. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4436827.

- Graham, A. J. (1982). "The Colonial Expansion of Greece". In John Boardman; N. G. L. Hammond (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. III (part 3) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521234476.

- Gruen, Erich S. (2005). Cultural borrowings and ethnic appropriations in antiquity. F. Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-08735-3.

- Krahe, Hans (1946). "Die illyrische Naniengebung (Die Götternamen)" (PDF). Jarhbücher f. d. Altertumswiss (in German). pp. 199–204.

- Lamboley, Jean-Luc (2000). "Les cultes de l'Adriatique méridionale à l'époque républicaine". In Christiane, Delplace (ed.). Les cultes polythéistes dans l'Adriatique romaine (in French). Ausonius Éditions. ISBN 978-2-35613-260-4.

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Marchesini, Simona (2009). Le lingue frammentarie dell'Italia antica: manuale per lo studio delle lingue preromane (in Italian). U. Hoepli. ISBN 978-88-203-4166-4.

- Matzinger, Joachim (2017). "The Lexicon of Albanian". In Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. 3. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-054243-1.

- McInerney, Jeremy (2014). A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3734-1.

- Pallottino, Massimo (1992). "The Beliefs and Rites of the Apulians, an Indigenous People of Southeastern Italy". In Bonnefoy, Yves (ed.). Roman and European Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06455-0.

- Salvemini, Biagio; Massafra, Angelo, eds. (2005). Storia della Puglia. Dalle origini al Seicento (in Italian). 1. Laterza. ISBN 8842077992.

- Small, Alastair (2014). "Pots, Peoples and Places in Fourth-Century B.C.E. Apulia". In Carpenter, T. H.; Lynch, K. M.; Robinson, E. G. D. (eds.). The Italic People of Ancient Apulia: New Evidence from Pottery for Workshops, Markets, and Customs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–35. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107323513.004. ISBN 978-1-139-99270-1.

- F. W. Walbank; A. E. Astin; M. W. Frederiksen; R. M. Ogilvie, eds. (1989). "Rome and Italy in the Early Third Century". The Cambridge Ancient History: The Rise of Rome to 220 B.C. VII (part 2) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23446-8.

- West, Morris L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199280759.

- Wilkes, J. J. (1992). The Illyrians. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.