Illinois Central Missouri River Bridge

The Illinois Central Missouri River Bridge, also known as the IC Bridge or the East Omaha Bridge, is a rail through truss double swing bridge across the Missouri River connecting Council Bluffs, Iowa, with Omaha, Nebraska. It is owned by the Canadian National Railway and is closed to all traffic. At 521 feet long, the second version of the bridge was the longest swing bridge in the world from when it was completed in 1903 through 1915.[1] In 1975 it was regarded as the third longest swing bridge.[2]

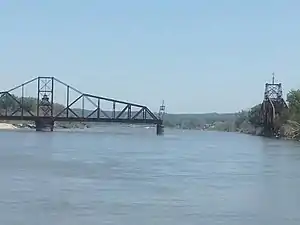

Illinois Central Missouri River Bridge | |

|---|---|

View from the south, looking upstream | |

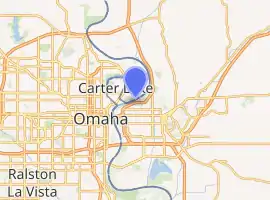

| Coordinates | 41°16′41″N 95°53′28″W |

| Carries | Railroad |

| Crosses | Missouri River |

| Locale | Council Bluffs, Iowa to Omaha, Nebraska |

| Owner | Illinois Central |

| Characteristics | |

| No. of spans | 2 |

| History | |

| Construction end | 1893 |

| Opened | 1903 |

| Location | |

| |

History

The East Omaha Bridge was originally built in 1893 and was owned by the Omaha Bridge and Terminal Railway Company. It was originally a single draw bridge.[3]

Reopened in January 1904,[4] the bridge was reconstructed again in 1908 by the American Bridge Company. In the reconstruction, there was discussion as to whether the bridge should be open to pedestrian and street traffic as well as rail traffic. Ultimately, it was limited to rail use only,[5] including commuter service between the two cities.

Illinois Central, or IC, started running through Omaha in January 1900, using the East Omaha Bridge for passenger trains from 1900 to 1921, and again from 1938 to 1939. In 1901, the bridge was targeted as part of a consolidation effort to bring together the street railway, electric light, and water utilities under public authority. "The plans for consolidation, in fact, include the union of interests in the cities of Omaha, South Omaha, and Council Bluffs..." Other utilities included the Omaha and Council Bluffs Street Railway and Bridge Company, the Council Bluffs Electric Light Company, and the Omaha Water Company, among others. These plans ultimately called for damming the Missouri River north of Omaha for an electricity plant; they ultimately were not actualized for this purpose,[6] and when consolidation did occur, it did not include the bridge.

Today, the Iowa swing span, still from the original bridge constructed in 1893, is of wrought iron; the Nebraska swing span was built in 1904 of steel. IC first gained rights to the bridge in 1899, and gained a controlling interest in 1902. The railroad took complete control of the Omaha Bridge and Terminal Railway Company in 1903, and was later bought by the Canadian National Railway, which currently owns the bridge.[7]

Features

The double swing was installed when the bridge was reconstructed in the first decade of the 1900s. It was necessary due to the changing channel of the river between when the bridge was originally constructed in the 1890s and when it was rebuilt. The bridge is composed of two 520' long draws.[4] Dating to the original construction of the bridge there were concerns about the effect of the river's flow on the bridge. In an 1895 Congressional Report the river's course change was predicted.[8] Precautionary steps were taken early in the bridge's history; however, the flow continued to affect it.

Completed in 1957,[9] the Gavins Point Dam controls the Missouri River flow at Omaha.[10] It has limited the flow of water at Omaha because of both droughts and decreased flow because of electricity needs met by the dam. Between that, levee building, and channelization of the river, starting in the 1950s the Iowa side of the bridge has spanned dry land, and the double swing became unnecessary. With the controlled flow of the Gavins Point Dam, starting in the 1960s the bridge was closed for rail traffic during the winter months when the Missouri River was shut down for barge traffic. In the 1970s the bridge the swing mechanism on the Iowa side was damaged in a fire of the equipment housing. In the spring when the river reopened the bridge would also be reopened for traffic. In the winter the Iowa side of the bridge would be swung open and closed by hooking a cable up to a bulldozer pulling it.

Closure

The bridge was taken out of service in 1980. Today the Iowa half is permanently wenched open to allow river traffic to cruise through without interruption. All railroad traffic through the Council Bluffs/Omaha area now crosses via the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge. A feasibility study conducted in the 1990s determined the need to keep the track and bridge in place in case of a problem with the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge.

Design

The current bridge features a drawspan of 521 feet with a fixed span of 560 feet carrying a double track railway between the trusses.[11]

References

- Waddell, John Alexander Low (1916). Bridge Engineering, Volume 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc – via Google Books.

- Marshall, John (1975). The Guinness Book of Rail Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. p. 99. ISBN 9780900424335 – via Google Books.

- White, J.T. (1904). The National cyclopaedia of American biography. p. 468. Retrieved March 19, 2011 – via Google Books.

- Poor's and Moodys Consolidated Manual. Volume 2, Part 1. Moody Manual Company. 1915. p. 398.

- "Omaha Bridge and Terminal Railway Company (Omaha, Neb.)". Nebraska State Historical Society. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved March 4, 2011. Communique regarding the East Omaha Bridge.

- "Gigantic Power Plant for Omaha". The Street Railway Journal. Street Railway Publishing Company. 18: 305. September 7, 1901 – via Google Books.

- "IC Swing Bridge". Bridgehunter.com. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- United States Congressional serial set. 1895. pp. 5–6 – via Google Books.

- "Gavins Point Dam & Powerplant". United States Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- Gaarder, Nancy (March 3, 2011). "No release at Gavins Point?". Omaha World Herald. Archived from the original on March 6, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Waddell, J.A.L. (1898). De pontibus: A pocket-book for bridge engineers. p. 156.

External links

- 1900 photo from Council Bluffs Public Library Special Collections.

- Historical image from before 1903.