Indian Rivers Inter-link

The Indian Rivers Inter-link is a proposed large-scale civil engineering project that aims to effectively manage water resources in India by linking Indian rivers by a network of reservoirs and canals to enhance irrigation and groundwater recharge, reduce persistent floods in some parts and water shortages in other parts of India.[1][2] India accounts for 18% of the world population and about 4% of the world’s water resources. One of the solutions to solve the country’s water woes is to link rivers and lakes.[3]

| Indian Rivers Inter-link | |

|---|---|

Rivers Inter-Link, Himalayan and Peninsular Components | |

| Country | India |

| Status | active |

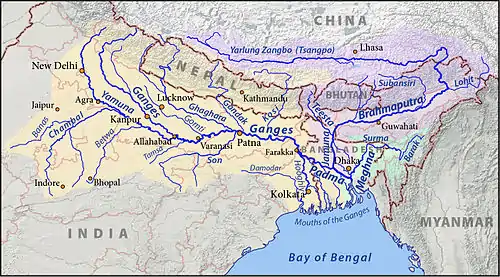

The Inter-link project has been split into three parts: a northern Himalayan rivers inter-link component, a southern Peninsular component and starting 2005, an intrastate rivers linking component.[4] The project is being managed by India's National Water Development Agency (NWDA), under its Ministry of Water Resources. NWDA has studied and prepared reports on 14 inter-link projects for Himalayan component, 16 inter-link projects for Peninsular component and 37 intrastate river linking projects.[4]

The average rainfall in India is about 4,000 billion cubic metres, but most of India's rainfall comes over a 4-month period – June through September. Furthermore, the rain across the very large nation is not uniform, the east and north gets most of the rain, while the west and south get less.[5][6] India also sees years of excess monsoons and floods, followed by below average or late monsoons with droughts. This geographical and time variance in availability of natural water versus the year round demand for irrigation, drinking and industrial water creates a demand-supply gap, that has been worsening with India's rising population.[6]

Proponents of the rivers inter-linking projects claim the answers to India's water problem is to conserve the abundant monsoon water bounty, store it in reservoirs, and deliver this water – using rivers inter-linking project – to areas and over times when water becomes scarce.[5] Beyond water security, the project is also seen to offer potential benefits to transport infrastructure through navigation, hydro power as well as to broadening income sources in rural areas through fish farming. Opponents are concerned about well-known environmental, ecological, social displacement impacts as well as unknown risks associated with tinkering with nature.[2] Others are concerned that some projects create international impact and the rights of nations such as Bangladesh must be respected and negotiated.[7]

History

- British colonial era

The Inter-linking of Rivers in India proposal has a long history. During the British colonial rule, for example, the 19th century engineer Arthur Cotton proposed the plan to interlink major Indian rivers in order to hasten import and export of goods from its colony in South Asia, as well as to address water shortages and droughts in southeastern India, now Andhra Pradesh and Orissa.[8]

- Post independence

In the 1970s, Dr. K.L. Rao, a dams designer and former irrigation minister proposed "National Water Grid".[9] He was concerned about the severe shortages of water in the South and repetitive flooding in the North every year. He suggested that the Brahmaputra and Ganga basins are water surplus areas, and central and south India as water deficit areas. He proposed that surplus water be diverted to areas of deficit. When Rao made the proposal, several inter-basin transfer projects had already been successfully implemented in India, and Rao suggested that the success be scaled up.[9]

In 1980, India’s Ministry of Water Resources came out with a report entitled "National Perspectives for Water Resources Development". This report split the water development project in two parts – the Himalayan and Peninsular components. Congress Party came to power and it abandoned the plan. In 1982, India financed and set up a committee of nominated experts, through National Water Development Agency (NWDA)[1] to complete detailed studies, surveys and investigations in respect of reservoirs, canals and all aspects of feasibility of inter-linking Peninsular rivers and related water resource management. NWDA has produced many reports over 30 years, from 1982 through 2013.[1] However, the projects were not pursued.

The river inter-linking idea was revived in 1999, after a new political alliance formed the central government, but this time with a major strategic shift. The proposal was modified to intra-basin development as opposed to inter-basin water transfer.[10]

- 21st century

By 2004, a different political alliance led by Congress Party was in power, and it resurrected its opposition to the project concept and plans. Social activists campaigned that the project may be disastrous in terms of cost, potential environmental and ecological damage, water table and unseen dangers inherent with tinkering with nature. The central government of India, from 2005 through 2013, instituted a number of committees, rejected a number of reports, and financed a series of feasibility and impact studies, each with changing environmental law and standards.[10][11]

In February 2012, while disposing a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) lodged in the year 2002, Supreme Court (SC) refused to give any direction for implementation of Rivers Interlinking Project. SC stated that it involves policy decisions which are part of legislative competence of state and central governments. However, SC directed the Ministry of Water Resources to constitute an experts committee to pursue the matter with the governments as no party had pleaded against the implementation of Rivers Interlinking Project.[12]

The need

- Drought, floods and shortage of drinking water

India receives about 4,000 cubic kilometers of rain annually, or about 1 million gallons of fresh water per person every year.[2] However, the precipitation pattern in India varies dramatically across distance and over calendar months. Much of the precipitation in India, about 85%, is received during summer months through monsoons in the Himalayan catchments of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basin.[13] The northeastern region of the country receives heavy precipitation, in comparison with the northwestern, western and southern parts. The uncertainty of start date of monsoons, sometimes marked by prolonged dry spells and fluctuations in seasonal and annual rainfall is a serious problem for the country.[1] The nation sees cycles of drought years and flood years, with large parts of west and south experiencing more deficits and large variations, resulting in immense hardship particularly the poorest farmers and rural populations. Lack of irrigation water regionally leads to crop failures and farmer suicides. Despite abundant rains during July–September, some regions in other seasons see shortages of drinking water. Some years, the problem temporarily becomes too much rainfall, and weeks of havoc from floods.[14] This excess-scarcity regional disparity and flood-drought cycles have created the need for water resources management. Rivers inter-linking is one proposal to address that need.[1][2]

- Population and food security

Population increase in India is the other driver of need for river inter-linking. India's population growth rate has been falling, but still continues to increase by about 10 to 15 million people every year. The resulting demand for food must be satisfied with higher yields and better crop security, both of which require adequate irrigation of about 140 million hectares of land.[15] Currently, just a fraction of that land is irrigated, and most irrigation relies on monsoon. River inter-linking is claimed to be a possible means of assured and better irrigation for more farmers, and thus better food security for a growing population.[1] In a tropical country like India with high evapotranspiration, food security can be achieved with water security which in turn is achieved with energy security to pump water to uplands from water surplus lower elevation river points up to sea level.[16][17]

- Salt export needs

When sufficient salt export is not taking place from a river basin to the sea in an attempt to harness the river water fully, it leads to river basin closure, and the available water in downstream area of the river basin closer to the sea becomes saline and/ or alkaline water. Land irrigated with saline or alkaline water gradually turns in to saline or alkali soils.[18][19][20] The water percolation in alkali soils is very poor leading to waterlogging problems. Proliferation of alkali soils would compel the farmers to cultivate rice or grasses only as the soil productivity is poor with other crops and tree plantations.[21] Cotton is the preferred crop in saline soils compared to many other crops.[22] Interlinking water surplus rivers with water deficit rivers is needed for the long term sustainable productivity of the river basins and for mitigating the anthropogenic influences on the rivers by allowing adequate salt export to the sea in the form of environmental flows.

- Navigation

India needs infrastructure for logistics and movement of freight. Using connected rivers as navigation is a cleaner, low carbon footprint form of transport infrastructure, particularly for ores and food grains.[1]

- Current reserves and loss in groundwater level

India currently stores only 30 days of rainfall, while developed nations strategically store 900 days worth of water demand in arid areas river basins and reservoirs. India’s dam reservoirs store only 200 cubic meters per person. India also relies excessively on groundwater, which accounts for over 50 percent of irrigated area with 20 million tube wells installed. About 15 percent of India’s food is being produced using rapidly depleting groundwater. The end of the era of massive expansion in groundwater use is going to demand greater reliance on surface water supply systems. Proponents of the project suggest India's water situation is already critical, and it needs sustainable development and management of surface water and groundwater usage.[23] Some proponents feel that India is not running out of water but water is running out of India.

Plan

The National perspective plan envisions about 150 million acre feet (MAF) (185 billion cubic metres) of water storage along with building inter-links.[24] These storages and the interlinks will add nearly 170 million acre feet of water for beneficial uses in India, enabling irrigation over an additional area of 35 million hectares, generation of 40,000 MW capacity hydro power, flood control and other benefits.

The total surface water available to India is nearly 1440 million acre feet (1776 billion cubic meters) of which only 220 million acre feet was being used in the year 1979. The rest is neither utilized nor managed, and it causes disastrous floods year after year. Up to 1979, India had built over 600 storage dams with an aggregate capacity of 171 billion cubic meters. These small storages hardly enable a seventh of the water available in the country to be utilized beneficially to its fullest potential.[24] From India-wide perspective, at least 946 billion cubic meters of water flow annually could be utilized in India, power generation capacity added and perennial inland navigation could be provided. Also some benefits of flood control would be achieved. The project claims that the development of the rivers of the sub-continent, each state of India, as well as its international neighbors stand to gain by way of additional irrigation, hydro power generation, navigation and flood control.[24] The project may also contribute to food security to the anticipated population peak of India.[24]

The Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna is a major international drainage basin which carries more than 1,000 million acre feet out of total 1440 million acre feet in India. Water is a scarce commodity and several basins such as Cauvery, Yamuna, Sutlej, Ravi and other smaller inter-State/intra-State rivers are short of water. 99 districts of the country are classified as drought prone, an area of about 40 million hectare is prone to recurring floods.[24] The inter-link project is expected to help reduce the scale of this suffering and associated losses.

The National Perspective Plan comprised, starting 1980s, of two main components:

- Himalayan Rivers Development, and

- Peninsular Rivers Development

An intrastate component was added in 2005.

Himalayan component

Himalayan Rivers Development envisages construction of storage reservoirs on the main Ganga and the Brahmaputra and their principal tributaries in India and Nepal along with inter-linking canal system to transfer surplus flows of the eastern tributaries of the Ganga to the West apart from linking of the main Brahmaputra with the Ganga.[24] Apart from providing irrigation to an additional area of about 22 million hectares the generation of about 30 million kilowatt of hydro-power, it will provide substantial flood control in the Ganga-Brahmaputra basin. The Scheme will benefit not only the States in the Ganga-Brahmaputra Basin, but also Nepal and Bangladesh, assuming river flow management treaties are successfully negotiated.[24]

The Himalayan component would consist of a series of dams built along the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers in India, Nepal and Bhutan for the purposes of storage. Canals would be built to transfer surplus water from the eastern tributaries of the Ganga to the west. This is expected to contribute to flood control measures in the Ganga and Brahmaputra river basins. It could also provide excess water for the Farakka Barrage to flush out the silt at the port of Kolkata.

By 2015, fourteen inter-links under consideration for Himalayan component are as follows, with feasibility study status identified:[25][26]

- Ghaghara–Yamuna link (Feasibility study complete)

- Sarda–Yamuna link (Feasibility study complete)

- Yamuna–Rajasthan link

- Rajasthan–Sabarmati link

- Kosi–Ghaghara link

- Kosi–Mechi link

- Manas–Sankosh–Tista–Ganga link

- Jogighopa–Tista–Farakka link

- Ganga–Damodar–Subernarekha link

- Subernarekha–Mahanadi link

- Farakka–Sunderbans link

- Gandak–Ganga link

- Chunar–Sone Barrage link

- Sone dam–Southern tributaries of Ganga link

Peninsular Component

This Scheme is divided in four major parts.

- Interlinking of Mahanadi-Godavari-Krishna-Palar-Pennar-Kaveri,

- Interlinking of West Flowing Rivers, North of Mumbai and South of Tapi,

- Inter-linking of Ken with Chambal and

- Diversion of some water from West Flowing Rivers

This component will irrigate an additional 25 million hectares by surface waters, 10 million hectares by increased use of ground waters and generate hydro power, apart from benefits of improved flood control and regional navigation.[24]

The main part of the project would send water from the eastern part of India to the south and west.[24] The southern development project (Phase I) would consist of four main parts. First, the Mahanadi, Godavari. Krishna and Kaveri rivers would all be inter-linked by canals. Reservoirs and dams would be built along the course of these rivers. These would be used to transfer surplus water from the Mahanadi and Godavari rivers to the south of India. Under Phase II, some rivers that flow west to the north of Mumbai and the south of Tapi would be inter-linked. The water would supply additional drinking water needs of Mumbai and provide irrigation in the coastal areas of Maharashtra. In Phase 3, the Ken and Chambal rivers would be inter-linked to serve regional water needs of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Over Phase 4, a number of west-flowing rivers in the Western Ghats, would be inter-linked for irrigation purposes to east flowing rivers such as Kaveri and Krishna.

The 800-km long Mahanadi-Godavari interlinking project would link River Sankosh originating from Bhutan to the Godavari in Andhra Pradesh through rivers like Teesta-Mahananda-Subarnarekha and Mahanadi.[27]

The inter-links under consideration for Peninsular component are as follows, with respective status of feasibility studies:[28][29]

- Almatti–Pennar Link (Feasibility study complete)(Part 1)

- Inchampalli–Nagarjunasagar Link (Halted construction by Telangana) (Part 1)

- Inchampalli–Pulichintala Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 1) Merged with Inchampalli–Nagarjunasagar Link

- Mahanadi–Godavari Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 1)

- Nagarjunasagar–Somasila Link (Part 1). It is remodelled as Srisailam to Somasila reservoir via Veligonda Project tunnels (fag end of construction) to reduce the cost of the link[30]

- Pamba–Anchankovil–Vaippar Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 4)

- Par–Tapi–Narmada Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 2)

- Parbati–Kalisindh–Chambal Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 3)

- Polavaram–Vijayawada Link (link canal constructed and partly in use with Pattiseema lift) (Part 1)

- Somasila–Grand Anicut Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 1)

- Srisailam–Pennar Link (link canals constructed and in use) (Part 1)

- Damanganga–Pinjal Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 2)

- Kattalai–Vaigai–Gundar Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 4)

- Ken–Betwa Link (Feasibility study complete) (Part 3)

- Netravati–Hemavati Link (Part 4)

- Bedti–Varada Link (Part 4)

Intra-state inter-linking of rivers

India approved and commissioned NWDA in June 2005 to identify and complete feasibility studies of intra-State projects that would inter-link rivers within that state.[31] The Governments of Nagaland, Meghalaya, Kerala, Punjab, Delhi, Sikkim, Haryana, Union Territories of Puducherry, Andaman & Nicobar islands, Daman & Diu and Lakshadweep responded that they have no intrastate river connecting proposals. Govt. of Puducherry proposed Pennaiyar – Sankarabarani link (even though it is not an intrastate project). The States Government of Bihar proposed 6 inter-linking projects, Maharashtra 20 projects, Gujarat 1 project, Orissa 3 projects, Rajasthan 2 projects, Jharkhand 3 projects and Tamil Nadu proposed 1 inter-linking proposal between rivers inside their respective territories.[31] Since 2005, NWDA completed feasibility studies on the projects, found 1 project infeasible, 20 projects as feasible, 1 project was withdrawn by Government of Maharashtra, and others are still under study.[32]

International comparisons

| |||||

The Indian Rivers Inter-link project is similar in scope and technical challenges as other major global river inter-link projects, such as:

- Rhine–Main–Danube Canal – completed in 1992, and also called the Europa Canal, it inter-links the Main river to the Danube river, thus connecting North Sea and Atlantic Ocean to the Black Sea. It provides a navigable artery between the Rhine delta at Rotterdam in the Netherlands to the Danube Delta in eastern Romania.[33] It is 171 km long, has the summit altitude (between the Hilpoltstein and Bachhausen locks) is 406 m above sea level, the highest point on Earth reachable by ships from the sea. In 2010, the inter-link provided navigation for 5.2 million tonnes of goods, mostly food, agriculture, ores and fertilizers, reducing the need for 250,000 truck trips per year.[34] The canal is also a source for irrigation, industrial water and power generation plants.[35]

- Illinois Waterway system consists of 541 kilometres of interlink that connects a system of rivers, lakes, and canals to provide a shipping connection from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River. It provides a navigation route; primary cargoes are coal to powerplants, chemicals and petroleum upstream, and agriculture produce downstream primarily for export.[36] The Illinois waterway is the principal source of industrial and municipal services water needs along its way; it serves the petroleum refining, pulp and paper processing, metal works, fermentation and distillation, and agricultural products industries.[37]

- Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway is a 377 kilometre man-made waterway that interlinks the Tennessee River to the Black Warrior-Tombigbee River in the United States.[38] The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway links major coal producing regions to coal consuming regions, and serves as commercial navigation for coal and timber products. Industries that utilize these natural resources have found the Waterway to be their most cost-efficient mode of transportation.[39] The water from the Tenn-Tom Waterway is a major source of industrial water supply, public drinking water supply, and irrigation along its way.[40]

- Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, completed in 1949, interlinks 8 rivers, and is located along the Gulf Coast of the United States. It is a navigable inland waterway running approximately 1700 kilometres from Florida to Texas.[41] It is the third busiest waterway in the United States, handling 70 million tonnes of cargo per year,[42] and a major low cost, ecologically friendly and low carbon footprint way to import, export and transport raw materials and products for industrial, chemical and petrochemical industries in the United States.[43] It has also become a significant source for fishing industry as well as for harvesting and shipping shellfish along the coast line of the United States.

- Dian Zhong Water Diversion Project is a water diversion project from the Jinsha River with 63 tunnels of total length 600 km to the Dianchi Lake in Yunnan province of China.[44] Once this project is completed, it would be world's longest tunnel relegating Delaware Aqueduct tunnel of 137 km to second place.

- Murray–Darling basin, this region in southern Australia with two rivers and associated watercourses was engineered for agriculture and a number of flows were altered over decades with the earliest alterations beginning in 1890.[45] Among the results were changes in seasonal flows causing numerous ecological problems including cyanobacteria blooms killing off fishes, high salinity, acidification, and decline in numerous species of plants and animals.[46] A study of attempts to repair the ecology that began in 2012 were reported as failing in 2017.[47]

Other completed rivers inter-linking projects include the Marne-Rhine Canal in France,[48][49] the All-American Canal and California State Water Project in the United States, South–North Water Transfer Project in China, etc.[50]

Discussion

Costs

The rivers inter-linking feasibility reports completed by 2013, suggest the following investment needs and potential economic impact:

| Inter-link project | Length (km) | Estimated Cost in the year 2003 or earlier# | New irrigation capacity added (hectares) | Potential Electricity generation capacity | Drinking & Industrial water added (MCM) | Reference | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krishna–Pennar Link | 587.2 | ₹6,599.80 crore (US$930 million) | 258,334 | 42.5 MW | 56 | [51] | Under Construction[52] |

| Godavari–Krishna Link | 299.3 | ₹26,289 crore (US$3.7 billion) | 287,305 | 70 MW | 237 | [53] | Completed[54] |

| Parbati Kalisindh Chambal | 243.7 | ₹6,114.5 crore (US$860 million) | 225,992 | 17 MW | 89 | [55] | |

| Nagarjunasagar Somasila Link | 393 | ₹6,320.54 crore (US$890 million) | 168,017 | 90 MW | 124 | [56] | |

| Ken Betwa Link | 231.5 | ₹1,988.74 crore (US$280 million) | 47,000 | 72 MW | 2,225 | [57] | |

| Srisailam Pennar Link | 203.6 | ₹1,580 crore (US$220 million) | 187,372 | 17 MW | 49 | [58] | |

| Damanganga Pinjal Link | 42.5 | ₹1,278 crore (US$180 million) | - | - | 44 | [59] | |

| Kaveri-Vaigai-Gundar Link | 255.6 | ₹2,673 crore (US$370 million) | 337,717 | - | 185 | [60] | |

| Polavaram-Vijayawada Link | 174 | ₹1,483.91 crore (US$210 million) | 314,718 | 72 MW | 664 | [61] | Under Construction[62] |

| Mahanadi Godavari Link | 827.7 | ₹17,540.54 crore (US$2.5 billion) | 363,959 | 70 MW | 802 | [63] | |

| Par Tapi Narmada Link | 395 | ₹6,016 crore (US$840 million) | 169,000 | 93 MW | 91 | [64] | |

| Pamba Achankovil Vaippar Link | 50.7 | ₹1,397.91 crore (US$200 million) | 91,400 | 500 MW | 150 | [65] |

#The cost conversion in US $ is at latest conversion price on the historical cost estimates in Indian rupees

Ecological and environmental issues

Some activists and scholars have, between 2002 and 2008, questioned the merits of Indian rivers inter-link projects, and questioned if appropriate study of benefits and risks to environment and ecology has been completed so far. Bandyopadhyay et al. claim there are knowledge gaps between the claimed benefits and potential threats from environment and ecological impact.[2] They also question whether the inter-linking project will deliver the benefits of flood control. Vaidyanathan claimed, in 2003, that there are uncertainty and unknowns about operations, how much water will be shifted and when, whether this may cause water logging, salinity/alkalinity and the resulting desertification in the command areas of these projects.[66] Other scholars have asked whether there are other technologies to address the cycle of droughts and flood havoc's, with less uncertainties about potential environmental and ecological impact.[67] Rivers may change their courses every (approximately) 100 years, so the interlinking may not be useful after 100 years. Interlinking may also lead to deforestation and cause ecological imbalances. Construction of environmentally benign multi purpose fresh water coastal reservoirs with massive storage capacities to inter link the Indian rivers can fully meet irrigation, domestic, industrial, ecological, environmental, etc. water requirements without social displacement impacts, poor river and ground water quality impacts and land or forest submergence with cheaper initial and operating costs.[68][69] India is not running out of water whereas water is running out of India without extracting its full potential benefits.[70]

Displacement of people and fisheries profession

Water storage and distributed reservoirs are likely to displace people – a rehabilitation process that has attracted concern of sociologists and political groups. Further, the inter-link would create a path for aquatic ecosystems to migrate from one river to another, which in turn may affect the livelihoods of people who rely on fishery as their income. Lakra et al., in their 2011 study, claim[71] large dams, interbasin transfers and water withdrawal from rivers is likely to have negative as well as positive impacts on freshwater aquatic ecosystem. As regards to the impact on fish and aquatic biodiversity, there could be positive as well as negative impacts.

Poverty and population issues

India has a growing population, and large impoverished rural population that relies on monsoon-irrigated agriculture. Weather uncertainties, and potential climate change induced weather volatilities, raise concerns of social stability and impact of floods and droughts on rural poverty. The population of India is expected to grow further at a decelerating pace and stabilize around 1.5 billion by 2050, or another 300 million people – the size of United States – compared to the 2011 census. This will increase demand for reliable sources of food and improved agriculture yields – both of which, claims India's National Council of Applied Economic Research,[5] require significantly improve irrigation network than the current state. The average rainfall in India is about 4,000 billion cubic metre, of which annual surface water flow in India is estimated at 1,869 billion cubic metre. Of this, for topological and other reasons, only about 690 billion cubic metre of the available surface water can be utilised for irrigation, industrial, drinking and ground water replenishment purposes. In other words, about 1,100 billion cubic metre of water is available, on average, every year for irrigation in India.[5] This amount of water is adequate for irrigating 140 million hectares. As of 2007, about 60% of this potential was realized through irrigation network or natural flow of Indian rivers, lakes and adoption of pumps to pull ground water for irrigation.

80% of the water India receives through its annual rains and surface water flow, happens over a 4-month period – June through September.[5][6] This spatial and time variance in availability of natural water versus year round demand for irrigation, drinking and industrial water creates a demand-supply gap, that only worsens with India's rising population. Proponents claim the answers to India's water problem is to conserve the abundant monsoon water bounty, store it in reservoirs, and use this water in areas which have occasional inadequate rainfall, or are known to be drought-prone or in those times of the year when water supplies become scarce.[5][72]

International issues

Hackre.in their 2007 report,[7] claim inter-linking of rivers initially appears to be a costly proposition in ecological, geological, hydrological and economical terms, in the long run the net benefits coming from it will far outweigh these costs or losses. However, they suggest that there is a lack of an international legal framework for the projects India is proposing. In at least some inter-link projects, neighboring countries such as Bangladesh may be affected, and international concerns for the project must be negotiated.

Technological developments

Cost of power generation by solar power projects would be below Rs. 1.0 per Kwh in few years.[73][74] Availability of cheaper, clean and perennial/renewable power would favour more water lifting/pumping and tunnels in the river link projects rather than purely gravity links to economize on cost, reduce construction time and reduce land submergence by optimum use of existing reservoirs/less storage, etc. Tunnelling technology/methodology has also undergone drastic improvements to make them alternate choice to the gravity open canal links with shortest distance and cost effective manner.[75]

Political views

BJP-led NDA government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee had propagated the idea of interlinking of rivers to deal with the problem of drought and different parts of the country at the same time.[11]

The Congress general secretary Rahul Gandhi said in 2009 that the entire idea of interlinking of rivers was dangerous and that he was opposed to interlinking of rivers as it would have "severe" environmental implications. Jairam Ramesh, a cabinet minister in former UPA government, said the idea of interlinking India's rivers was a "disaster", putting a question mark on the future of the ambitious project.[76]

Karunanidhi, whose DMK has been a key ally of the Congress-led UPA at the Centre, wrote that linking rivers at the national level perhaps is the only permanent solution to the water scarcity problem in the country. Karunanidhi said the government should make an assessment of the project's feasibility starting with the south-bound rivers. DMK for 2014 general elections added Nationalisation and inter-linking of rivers to its manifesto.

Kalpasar Project is an irrigation project which envisages storing Narmada River water in an off-shore fresh water reservoir located in Gulf of Khambhat sea for further pumping to arid Sourashtra region for irrigation use. It is one of the preferred project for implementation proposed by the UPA chief, Sonia Gandhi in 2009.[77]

Progress

On 16 September 2015, first linking was completed of rivers Krishna and Godavari.[78] It is still under review. But it isn't considered as a true river interlinking as it is just a small lift irrigation with few lines of pipes.

See also

- Environment of India

- Kalpasar Project

- List of rivers by dissolved load

- Ground water in India

- Interstate River Water Disputes Act

- Irrigation in India

- List of drainage basins by area

- List of rivers of India by discharge

- List of rivers by discharge

- List of dams and reservoirs in India

- Polavaram Project

- Pollution of the Ganges

- National Water Policy

- Saemangeum Seawall

- Water scarcity in India

- Water supply and sanitation in India

- Water pollution in India

References

- National Water Development Agency Ministry of Water Resources, Govt of India (2014)

- Jayanta Bandyopadhyay and Shama Perveen (2003), The Interlinking of Indian Rivers: Some Questions on the Scientific, Economic and Environmental Dimensions of the Proposal Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine IIM Calcutta, IISWBM, Kolkata

- http://greencleanguide.com/2013/09/13/national-water-policy/

- "National water Development Agency (NWDA) Studies". Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Suman Bery, Economic Impact of Interlinking of Rivers Programme NCAER, India

- IWMI Research Report 83. "Spatial variation in water supply and demand across river basins of India" (PDF). Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Misra et al., Proposed river-linking project of India: a boon or bane to nature, Environmental Geology, February 2007, Volume 51, Issue 8, pp 1361-1376

- Elizabeth Hope and William Digby, General Sir Arthur Cotton, R. E., K. C. S. I.:His Life and Work at Google Books

- A.K. Singh (2003), Interlinking of Rivers in India: A Preliminary Assessment, New Delhi

- Sharon Gourdji, Carrie Knowlton and Kobi Platt, Indian Inter-linking of Rivers: A Preliminary Evaluation M.S. Thesis, University of Michigan (May 2005)

- Koshy & Kanekal, SC revives NDA dream to interlink rivers LiveMint & The Wall Street Journal (28 February 2012)

- "Paras 62 to 64, WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 668 OF 2002", The Supreme Court of India, Civil Original Jurisdiction, Government of India (2002)

- "No water No growth" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "State wise flood damage statistics in India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Brown, Lester R. (29 November 2013). "India's dangerous 'food bubble'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014. Alt URL

- Pulakkat, Hari (9 June 2016). "Why rains will not solve the country's growing ground water problems". The Economic Times. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "Beyond hydropower: towards an integrated solution for water, energy and food security in South Asia". doi:10.1080/07900627.2019.1579705.

- J. Keller; A. Keller; G. Davids. "River basin development phases and implications of closure" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- David Seckler. "The New Era of Water Resources Management: From "Dry" to "Wet" Water Savings" (PDF). Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- Andrew Keller; Jack Keller; David Seckler. "Integrated Water Resource Systems: Theory and Policy Implications" (PDF). Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Oregon State University, USA. "Managing irrigation water quality" (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "Irrigation water quality—salinity and soil structure stability" (PDF). Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "India's water economy bracing for a turbulent future, World Bank report, 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- National perspectives for water resources development (accessdate 12 June 2014)

- Himalayan Component WRIS, Govt of India (Accessed: 27 November 2015)

- Himalayan Component Link Proposal NWDA, Govt of India (Accessed: June 2014)

- "Centre revises river linking project", The Times of India, 4 February 2016

- Summary of Link Proposal NWDA, Govt of India (Accessed: June 2014)

- Feasibility Studies – Peninsular components Govt of India

- "Andhra to Link Godavari, Penna and Palar Rivers". Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- National water Development Agency (NWDA) Studies Govt of India (Accessdate=9 June 2014)

- Intra – State river link proposals received from the State Governments NDWA, Government of India (2013)

- "Ein Traum wird Wirklichkeit" Die Fertigstellung des Main-Donau-Kanals (A Dream Becomes Reality: the Completion of the Main-Danube Canal), Siegfried Zelnhefer, July 1992

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.zaoerv.de/41_1981/41_1981_4_a_731_807.pdf

- United States Army Corps of Engineers. "Chapter 6. The Illinois Waterway Archived 9 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine". page 3. 3 June 2005.

- Water Chemistry of the Illinois Waterway State of Illinois, USA

- "Tenn-Tom Waterway Key Components" Archived 27 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine (2009), Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority

- "Economic Impacts of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway." 2009. Troy University.

- McKee and McAnally (2008), Water Budget of Tombigbee River – Tenn-Tom Waterway from Headwaters to Junction with Black Warrior River Mississippi State University, pp 11

- Lynn M. Alperin. "History of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2005.

- "Gulf Intracoastal Waterway".

- Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Texas DOT, USA

- "Dian Zhong Water Diversion Project". November 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- O'Gorman, Emily (2012). Flood Country: An Environmental History of the Murray-Darling Basin. CSIRO publishing. pp. 81–100.

- Pittock, J; Finlayson, C M (2013). "Climate change adaptation in the Murray-Darling Basin: Reducing resilience of wetlands with engineering". Australasian Journal of Water Resources. 17 (2): 161–169. doi:10.7158/W13-021.2013.17.2. ISSN 1324-1583. S2CID 130352258.

- Reese, April (13 December 2017). "Groundbreaking Australian Murray–Darling water agreement in peril". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-017-08428-6. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Jefferson, David (2009). Through the French Canals. Adlard Coles Nautical. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-4081-0381-4.

- McKnight, Hugh (2005). Cruising French Waterways, 4th Edition. Sheridan House. ISBN 978-1574092103.

- "History of the State Water Project". State Water Contractors. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Krishna Pennar Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Sarma, Ch R. S. "Naidu launches Godavari-Penna linkage project; vows to make AP drought-proof". @businessline. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Godavari–Krishna Link NDWA, Govt of India

- First River Linkage | Krishna Meets Godavari, retrieved 18 January 2020

- Parbati Kalisindh Chambal Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Nagarjunasagar Somasila Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Ken Betwa Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Srisailam Pennar Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Damanganga Pinjal Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Cauvery-Vaigai-Gundar link NDWA, Govt of India

- Polavaram-Vijayawada link NDWA, Govt of India

- "chandrababu-naidu-inspects-construction-work-polavaram-project". www.aninews.in. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Mahanadi Godavari Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Par Tapi Narmada Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Pamba Achankovil Vaippar Link NDWA, Govt of India

- Vaidyanathan, (2003) ‘Interlinking of Rivers’ The Hindu, 26 March

- Monirul Qader Mirza et al., Interlinking of Rivers in India: Issues and Concerns, ISBN 978-0415404693, Taylor & Francis, page xi

- "Efficacy of coastal reservoirs to address India's water shortage by impounding excess river flood waters near the coast (pages 49 and 19)". Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "International Association for Coastal Reservoir Research". Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "India is not running out of water, water is running out of India". 26 March 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Lakra et al, River inter linking in India: status, issues, prospects and implications on aquatic ecosystems and freshwater fish diversity, Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, September 2011, Volume 21, Issue 3, pp 463-479

- Monirul Qader Mirza et al., Interlinking of Rivers in India: Issues and Concerns, ISBN 978-0415404693, Taylor & Francis

- "Mexico's Energy Auction Just Logged the Lowest Solar Power Price on the Planet". 21 November 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- "The Birth of a New Era in Solar PV — Record Low Cost On Saudi Solar Project Bid". 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "China considering plan to make Xinjiang desert a new California". November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Interlinking of rivers buried, Jairam says idea a disaster Indian Express (6 October 2009)

- "Kalpasar to break ground in 2013". Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Balachandran, Manu (21 September 2015), Why India's $168 billion river-linking project is a disaster-in-waiting, Scroll.in

External links

- Major and medium dams & barrages location map in India

- The Guardian's Ravi S Jha writes on the project

- BBC report on the Project

- BBC Report on Bangladeshi objections

- Economic Impact of Interlinking of Rivers Programme

- National Water Development Agency official website, Ministry of Water Resources – Government of India

- Anatomy of Interlinking Rivers in India: A Decision in Doubt, paper by A.C. Shukla and Vandana Asthana

- அனைத்து மாநிலங்களும் வளம் பெற தேசிய அதி திறன் நீர்வழிச்சாலை வேண்டும்

- தமிழக நதிகளை இணைத்தால் ஆண்டுக்கு ரூ.5,000 கோடி வருமானம்!

- நீர்வழி திட்டத்திற்கு முன்னுரிமை கொடுப்போம்!

- Dr. Abdul Kalam Article about Indian Rivers Inter-link

.png.webp)