Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is a point-and-click adventure game by LucasArts originally released in 1992. Almost a year later, it was reissued on CD-ROM as an enhanced "talkie" edition with full voice acting and digitized sound effects. In 2009, this version was also released as an unlockable extra of the Wii action game Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings, and as a digitally distributed Steam title. The seventh game to use the script language SCUMM, Fate of Atlantis has the player explore environments and interact with objects and characters by using commands constructed with predetermined verbs. It features three unique paths to select, influencing story development, gameplay and puzzles. The game used an updated SCUMM engine and required a 286-based PC, although it still runs as a real-mode DOS application. The CD talkie version required EMS memory enabled to load the voice data.

| Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis | |

|---|---|

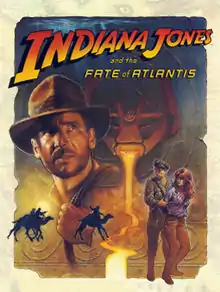

Lead artist William Eaken's cover artwork depicts the main characters Indiana Jones and Sophia Hapgood. | |

| Developer(s) | LucasArts |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts |

| Director(s) | Hal Barwood |

| Producer(s) | Shelley Day |

| Designer(s) | Hal Barwood Noah Falstein |

| Artist(s) | William Eaken Mark Ferrari |

| Writer(s) | Hal Barwood Noah Falstein |

| Composer(s) | Clint Bajakian Peter McConnell Michael Land |

| Engine | SCUMM |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, FM Towns, MS-DOS, Macintosh, Wii |

| Release | June 1992 Wii

|

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The plot is set in the fictional Indiana Jones universe and revolves around the eponymous protagonist's global search for the legendary sunken city of Atlantis. Sophia Hapgood, an old co-worker of Indiana Jones who gave up her archaeological career to become a psychic, supports him along the journey. The two partners are pursued by the Nazis who seek to use the power of Atlantis for warfare, and serve as the adventure's antagonists. The story was written by Hal Barwood and Noah Falstein, the game's designers, who had rejected the original plan to base it on an unused movie script. They came up with the final concept while researching real-world sources for a suitable plot device.

Fate of Atlantis was praised by critics and received several awards for best adventure game of the year. It became a million-unit seller and is widely regarded as a classic of its genre today. Two concepts for a supposed sequel were conceived, but both projects were eventually canceled due to unforeseen problems during development. They were later reworked into two separate Dark Horse Comics series by Lee Marrs and Elaine Lee, respectively.

Gameplay

Fate of Atlantis is based on the SCUMM story system by Ron Gilbert, Aric Wilmunder, Brad P. Taylor, and Vince Lee,[1] thus employing similar gameplay to other point-and-click adventures developed by LucasArts in the 1980s and 1990s.[2] The player explores the game's static environments while interacting with sprite-based characters and objects; they may use the pointer to construct and give commands with a number of predetermined verbs such as "Pick up", "Use" and "Talk to".[3] Conversations with non-playable characters unfold in a series of selectable questions and answers.[4]

Early on, the player is given the choice between three different game modes, each with unique cutscenes, puzzles to solve and locations to visit: the Team Path, the Wits Path, and the Fists Path.[5] In the Team Path, protagonist Indiana Jones is joined by his partner Sophia Hapgood who will provide support throughout the game.[5] The Wits Path features an abundance of complex puzzles, while the Fists Path focuses heavily on action sequences and fist fighting, the latter of which is completely optional in the other two modes.[5] Atypical for LucasArts titles, it is possible for the player character to die at certain points in the game, though dangerous situations were designed to be easily recognizable.[6] A score system, the Indy Quotient Points, keeps track of the puzzles solved, the obstacles overcome and the important objects found.[6]

Plot

The story of Fate of Atlantis is set in 1939, on the eve of World War II.[7] At the request of a visitor named Mr. Smith, archaeology professor and adventurer Indiana Jones tries to find a small statue in the archives of his workplace Barnett College. After Indy retrieves the horned figurine, Smith uses a key to open it,[8] revealing a sparkling metal bead inside. Smith then pulls out a gun and escapes with the two artifacts, but loses his coat in the process. The identity card inside reveals "Smith" to be Klaus Kerner, a Nazi agent.[9] Also inside the coat is an old magazine containing an article about an expedition on which Jones collaborated with a young woman named Sophia Hapgood, who has since given up archaeology to become a psychic.[10]

Fearing that she might be Kerner's next target, Indy travels to New York City to warn her and to find out more about the mysterious statue.[11] There, he interrupts her lecture on the culture and downfall of Atlantis,[12] and the two return to Sophia's apartment. They discover that Kerner ransacked her office in search of Atlantean artifacts, but Sophia says that she keeps her most valuable item, her necklace, with her.[13] She owns another of the shiny beads, now identified as the mystical metal orichalcum, and places it in the medallion's mouth, invoking the spirit of the Atlantean king Nur-Ab-Sal.[14] She explains that a Nazi scientist, Dr. Hans Ubermann, is searching for the power of Atlantis to use it as an energy source for warfare.[15]

Sophia then gets a telepathic message from Nur-Ab-Sal, instructing them to find the Lost Dialogue of Plato, the Hermocrates, a book that will guide them to the city.[16] After gathering information, Indy and Sophia eventually find it in a collection of Barnett College.[17] Correcting Plato's "tenfold error", a mistranslation from Egyptian to Greek, the document pinpoints the location of Atlantis in the Mediterranean, 300 miles from the Kingdom of Greece, instead of 3000 as mentioned in the dialogue Critias.[18][19] It also says that in order to gain access to the Lost City and its colonies, three special engraved stones are required.[20] At this point, the player has to choose between the Team, Wits, or Fists path, which influences the way the stones are acquired. In all three paths, Jones meets an artifact dealer in Monte Carlo, ventures to an archaeological dig in Algiers, explores an Atlantean labyrinth in Knossos on Crete, and Sophia gets captured by the Nazis. Other locations include the remains of a small Atlantean colony on Thera,[21] a hydrogen balloon and a Nazi submarine.

The individual scenarios converge at this point as Indiana makes his way to the underwater entrance of Atlantis near Thera and starts to explore the Lost City. He figures out how to use various Atlantean devices and even produce orichalcum beads. With this knowledge he saves Sophia from a prison, and they make their way to the center of Atlantis, where her medallion guides them to the home of Nur-Ab-Sal. The spirit of the Atlantean king takes full possession of Sophia[22] and it is only by a trick that Indy rids her of the necklace and destroys it, thus freeing her. Meanwhile, they notice grotesquely deformed bones all over the place. They advance further and eventually reach a large colossus the inhabitants of the city built trying to transform themselves into gods. They had hoped using ten orichalcum beads at a time would enable them to control the water with the powers they gained, keeping the sea level down to prevent an impending catastrophe.[23]

Unknowingly, Indiana starts the machine, upon which Kerner, Ubermann, and Nazi troops invade the place and announce their intention to use the machine to become gods. The machine was responsible for creating the mutated skeletons seen earlier, but the Nazis believe that it will work on them due to their Aryan qualities. Kerner insists to step onto the platform first, claiming himself to be most suitable for godhood. After Jones mentions Plato's tenfold error, Kerner decides to use one bead instead of ten. He is turned into a horribly deformed and horned creature, and jumps into the surrounding lava.[23] Indiana is forced to step on the platform next but threatens Ubermann with eternal damnation once he is a god. Fearing his wrath, Ubermann uses the machine on himself, feeding it one hundred beads. He is turned into a green ethereal being, but his form becomes unstable and he flies apart with an agonized scream.

Two alternative bad endings see one of the protagonists undergo the second transformation if Indiana could not convince Ubermann to use the machine instead, or if Sophia was not freed from her prison and Nur-Ab-Sal's influence. In the happy ending, Atlantis succumbs to the eruption of the still active volcano as the duo flees from the city. The final scene depicts Indiana kissing Sophia on top of the escape submarine, to comfort himself for the lack of evidence for their discovery.[24]

Development

At the time a sequel to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure was decided, most of the staff of Lucasfilm Games was occupied with other projects such as The Secret of Monkey Island and The Dig.[25][26] Designer Hal Barwood had only created two computer games on his own before, but was put in charge of the project because of his experience as a producer and writer of feature films.[25][26] The company originally wanted him to create a game based on Indiana Jones and the Monkey King/Garden of Life, a rejected script written by Chris Columbus for the third movie[26] that would have seen Indiana looking for Chinese artifacts in Africa.[26][27] However, after reading the script Barwood decided that the idea was substandard, and requested to create an original story for the game instead.[26] Along with co-worker Noah Falstein, he visited the library of George Lucas' workplace Skywalker Ranch to look for possible plot devices.[26] They eventually decided upon Atlantis when they looked at a diagram in "some cheap coffee-table book on the world's unsolved mysteries", which depicted the city as built in three concentric circles.[26] Falstein and Barwood originally considered the mythical sword Excalibur as the story's plot device, but the idea was scrapped because it wouldn't have easily given Indiana Jones a reason to go anywhere except England.[28]

Writing the story involved extensive research on a plethora of pseudo-scientific books.[29] Inspiration for the mythology in the game, such as the description of the city and the appearance of the metal orichalcum, was primarily drawn from Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias, and from Ignatius Loyola Donnelly's book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World that revived interest in the myth during the nineteenth century.[25] The magical properties of orichalcum and the Atlantean technology depicted in the game were partly adopted from Russian spiritualist Helena Blavatsky's publications on the force vril.[25] The giant colossus producing gods was based on a power-concentrating device called "firestone", formerly described by American psychic Edgar Cayce.[25]

Once Barwood and Falstein completed the rough outline of the story, Barwood wrote the actual script,[30] and the team began to conceive the puzzles and to design the environments.[25] The Atlantean artifacts and architecture devised by lead artist William Eaken were made to resemble those of the Minoan civilization, while the game in turn implies that the Minoans were inspired by Atlantis.[31][32] Barwood intended for the Atlantean art to have an "alien" feel to it, with the machines seemingly operating on as yet unknown physics rather than on magic.[32] The backgrounds were first pencil sketched, given a layer of basic color and then converted and touched up with 256-colors.[33] Mostly they were mouse-drawn with Deluxe Paint, though roughly ten percent were paintings scanned at the end of the development cycle.[31] As a consequence of regular design changes, the images often had to be revised by the artists.[32] Character animations were fully rotoscoped with video footage of Steve Purcell for Indiana's and Collette Michaud for Sophia's motions.[26] The main art team that consisted of Eaken, James Dollar and Avril Harrison was sometimes consulted by Barwood to help out with the more graphical puzzles in the game, such as a broken robot in Atlantis.[31][32]

The addition of three different paths was suggested by Falstein and added about six more months of development time, mainly because of all the extra dialogue that had to be implemented for the interaction between Indiana and Sophia.[26] Altogether, the game took around two years to finish, starting in early 1990,[26] and lasting up to the floppy disk release in June 1992.[34] The only aspect Barwood was not involved in at all was the production of voices for the enhanced "talkie" edition released on CD-ROM in May 1993, which was instead handled by Tamlynn Barra.[26][35] The voice-over recordings for the approximately 8000 lines of dialogue took about four weeks, and were done with actors from the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. Harrison Ford was not available to record Indiana Jones's voice, so a substitute actor Doug Lee was used.[36] The "talkie" version was later included as an extra game mode in the Wii version of the 2009 action game Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings,[37] and distributed via the digital content delivery software Steam as a port for Windows XP, Windows Vista and Mac OS X that same year. The versions on the Wii and available on Steam have improved MIDI versions of the soundtrack, along with both voices and text.[38][39]

The package illustration for Fate of Atlantis was inspired by the Indiana Jones movie posters of Drew Struzan.[31] It was drawn by Eaken within three days, following disagreements with the marketing department and an external art director over which concept to use.[26][31][32] Clint Bajakian, Peter McConnell and Michael Land created the soundtrack for the game, arranging John Williams' main theme "The Raiders March" for a variety of compositions.[1] The DOS version uses sequenced music played back by either an internal speaker, the FM synthesis of an AdLib or Sound Blaster sound card, or the sample-based synthesis of a Roland MT-32 sound module.[40] During development of the game, William Messner-Loebs and Dan Barry wrote a Dark Horse Comics series based on Barwood's and Falstein's story, then titled Indiana Jones and the Keys to Atlantis.[41] In an interview, Eaken mentioned hour-long meetings of the development team trying to come up with a better title than Fate of Atlantis, though the staff members could never think of one and always ended up with names such as "Indiana Jones Does Atlantis".[31][32] The final title was Barwood's idea, who first had to convince the company's management and the marketing team not to simply call the game "Indy's Next Adventure".[26]

LucasArts developed a port of the enhanced edition for the Sega CD,[42] but the release was eventually canceled because The Secret of Monkey Island failed to be much of a commercial success on the platform.[43] The arcade-style game Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: The Action Game designed by Attention to Detail was released almost simultaneously with its adventure counterpart, and loosely follows its plot.[44]

Reception

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Dragon | |

| The One | 88%[46] |

| Amiga Computing | 88%[47] |

| Amiga Format | 92%[48] |

| Commodore User | 90%[49] |

| PC Review | 9/10[50] |

According to Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts, Fate of Atlantis was "a commercial hit."[51] Noah Falstein reported that it was LucasArts' all-time most successful adventure title by 2009, at which point its lifetime sales had surpassed 1 million units. He recalled that the game's player audience was 30% female, a higher figure than most LucasArts titles had achieved before its release.[52]

Reviewers from Game Informer, Computer Game Review, Games Magazine and Game Players Magazine named Fate of Atlantis the best adventure game of the year, and it was later labeled a "classic" by IGN.[53][26][54] Patricia Hartley and Kirk Lesser of Dragon called it "terrific" and "thought-provoking". They lauded the "Team, Wits, Fists" system for increasing the game's replay value, but believed that the Team option was the best. The reviewers summarized it as a "must-buy".[45] Lim Choon Wee of the New Straits Times praised the game's graphics and arcade-style sequences. About the former, he wrote, "The attention to detail is excellent, with great colours and brilliant sprite animation." He echoed Hartley's and Lesser's opinion that "Team" was the best mode of the game. Wee ended his review by calling Fate of Atlantis "a brilliant game, even beating Secret of Monkey Island 2."[55]

Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World in September 1992 praised its setting for containing the "right combination of gravity, silliness, genuine scholarship and mystical mumbo-jumbo", and called it a "strong enough storyline to hold its own next to any of the Indy films." He highly praised the game's Team, Wits, Fists system, about which he wrote, "Never before has a game paid this much attention to what the player wants." He also enjoyed its graphics and varied locales. Although he cited the pixelated character sprites and lack of voice acting as low points, Ardai summarized Fate of Atlantis as an "exuberant, funny, well-crafted and clever game" that bettered its predecessor, The Last Crusade.[56] QuestBusters also praised the game, stating that it "is not only the best adventure ever done by LucasArts ... but is also probably the nicest graphic adventure ever ... just about perfect in all areas". The reviewer wrote "Atlantis shines in 256 colors" and that "the musicians and sound effects specialists deserve a tip of the hat", stating that the audio "completes the effect of playing a movie". He described the puzzles as quite creative and certainly fair" and liked the multiple solutions. The reviewer concluded that the game was "a must-buy for all adventurers" and "gets my vote ... for 'Best Quest of the Year'", tied with Ultima Underworld, "both of which redefine the state-of-the-art in their respective genres".[57]

The following year, Ardai stated that "Unlike many recent CD-ROM upgrades, which have been embarrassing and amateurish", the CD-ROM version "has the stamp of quality all over it", with the added dialogue and sound effects "like taking a silent film and turning it into a talkie ... It's hard to go back to reading text off a monitor after experiencing a game like this". He concluded that "LucasArts has done an impeccable job ... a must-see".[58] In April 1994 the magazine said that "the disk version of Atlantis is fun, but in many ways, it's just another adventure game", but speech made the CD version "a fine approximation of an Indiana Jones film, with you as the main character", concluding "If you want a good reason to purchase a CD-ROM, look no further".[59] Andy Nuttal of Amiga Format wrote, "The puzzles are very well thought-out, with some exquisite, subtle elements that give you a real kick when you solve them." He noted that the game is "littered with elements that are genuinely funny". His sole complaint was about the game's linearity compared to Monkey Island 2; but he finished by saying, "It's a minor point, anyway, and it shouldn't put you off buying what is one of the best Amiga adventures ever."[48] In 2008, Retro Gamer Magazine praised it as "a masterful piece of storytelling, and a spellbinding adventure".[26]

In 1992 Computer Gaming World named Fate of Atlantis as one of the year's four best adventure games.[60] It was nominated for an award at the 1993 Game Developers Conference.[61] In 1994, PC Gamer US named the CD-ROM version of Fate of Atlantis as the 38th best computer game ever. The editors wrote that the floppy release was "a terrific game", but that the CD-ROM edition improved upon it by "set[ting] a new industry standard for voice acting."[62] That same year, PC Gamer UK named it the 13th best computer game of all time. The editors called it "a sumptuous feast for adventure and Indy fans alike."[63] In 1996, Computer Gaming World declared Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis the 93rd-best computer game ever released.[64] In 2011, Adventure Gamers named Fate of Atlantis the 11th-best adventure game ever released.[65]

In 1998, PC Gamer declared it the 41st-best computer game ever released, and the editors called it "a milestone achievement for LucasArts, this genre's greatest exponent, and it remains required playing for adventurers everywhere".[66]

Legacy

After the release of the game, a story for a supposed successor in the adventure genre was conceived by Joe Pinney, Hal Barwood, Bill Stoneham, and Aric Wilmunder.[67] Titled Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix, it was set after World War II and featured Nazis seeking refuge in Bolivia, trying to resurrect Adolf Hitler with the philosophers' stone.[29] The game was in development for 15 months before it was showcased at the European Computer Trade Show.[29]

However, when the German coordinators discovered how extensively the game dealt with Neo-Nazism, they informed LucasArts about the difficulty of marketing the game in their country.[68] As Germany was an important overseas market for adventure games, LucasArts feared that the lower revenues would not recoup development costs, and subsequently canceled the game.[68] The plot was later adapted into a four-part Dark Horse Comics series by Lee Marrs,[67] published monthly from December 1994 to March 1995.[69][70] In an interview, Barwood commented that the development team should have thought about the story more thoroughly beforehand, calling it insensitive and not regretting the cancellation of the title.[68]

Another follow-up game called Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny was planned, which revolved around the Spear of Longinus.[68] Development was outsourced to a small studio, but eventually stopped as LucasArts did not have experience with the supervision of external teams.[68] Elaine Lee loosely reworked the story into another four-part comic book series, released from April to July 1995.[71][72]

References

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Scene: staff credits.

- Shepard, Mark (1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Manual. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. p. 14.

- Shepard, Mark (1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Manual. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. p. 3.

- Shepard, Mark (1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Manual. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. p. 7.

- Shepard, Mark (1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Manual. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. p. 6.

- Shepard, Mark (1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Manual. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. p. 11.

- Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis back cover. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. June 1992.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Klaus Kerner: ...did you find a lock to match my key?

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Indiana Jones: Klaus Kerner, huh? Marcus Brody: Good Lord, Indy, the man's some sort of agent from the Third Reich. What does a SPY want with a PHONY STATUE?

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Marcus Brody: Look what else our friend was carrying, an old copy of National Archaeology, and there you are in ICELAND. Indiana Jones: Yeah...field supervisor for the Jastro expedition, my first real job. Marcus Brody: Who's the woman? Indiana Jones: Sophia Hapgood. She was my assistant, a spoiled rich kid from Boston rebelling against her family. Marcus Brody: Where is she now? Indiana Jones: She gave up archaeology to become a PSYCHIC.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Marcus Brody: Indy, Kerner found YOU, what if he finds HER? We should WARN the woman. Indiana Jones: You're right. I want to know more about that statue!

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Sophia Hapgood: Here, my friends, is ATLANTIS as it might have appeared in its heyday...glorious...prosperous...socially and technically advanced beyond our wildest dreams! [...] However it happened, on that fateful day when proud Atlantis sank beneath the waves...or perhaps it was a volcanic eruption, and SOMETHING remains even now.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Sophia Hapgood: Kerner missed the grand prize... Indiana Jones: What? Sophia Hapgood: ...my necklace.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Sophia Hapgood: Watch closely. The bead is made of ORICHALCUM, the mystery metal first mentioned by Plato. Now I'll place it in the medallion's mouth. Did you see that? Indiana Jones: Yeah. Creepy. Is your electric bill paid up? Sophia Hapgood: That was Nur-Ab-Sal. His spirit is close!

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Sophia Hapgood: Listen to this... "Germans claim victory in worldwide race to smash the uranium atom. Chief scientist Dr. Hans Ubermann announces plan to harness new sources of energy for the Third Reich." Indiana Jones: So? Practical results are years away. Sophia Hapgood: Of course they are. That's why they're looking for the POWER OF ATLANTIS.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Sophia Hapgood: Shhhh! ...I'm getting something! Nur-Ab-Sal SPEAKS...he bids us find the...what...a book...yes...the LOST DIALOGUE OF PLATO!

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Indiana Jones: I believe BARNETT COLLEGE owns the Ashkenazy/Dunlop/Pearce/Sprague/Ward collection.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Hermocrates: In shame I hereby recant the time and place whereof Critias spoke. In rendering Egyptian into Greek he made a tenfold error. Instead of lying 3,000 miles hence, Atlantis may well have been 30,000 miles away. Or perhaps it was less than 300 miles from our own shores.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Indiana Jones: Didn't you notice Plato's tenfold numbering error? Sophia Hapgood: So he got his dates mixed up, why is that so important? Indiana Jones: Plato's error means distances could ALSO be wrong. Sophia Hapgood: So what if they are? Indiana Jones: If Plato is right, Atlantis is in the MEDITERRANEAN. Sophia Hapgood: You mean-- 300 miles from Greece instead of 3,000. Indiana Jones: Yes! The cradle of civilization. Sophia Hapgood: You could be right. He once told me he came from the middle of the world. That's what "Mediterranean" means!

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Hermocrates: Gates of the kingdom opened only with the aid of special stones. At many outposts, a Sunstone sufficed [...] At the Greater Colony a Moonstone was also needed [...] To approach Atlantis itself a Worldstone was required as well [...]

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Alain Trottier: More important, I know where to find an entrance to the Lost City itself. [...] It's on the island of Thera, South of Greece. [...] You've read about the Lesser Colony in Plato's Lost Dialogue, have you not? [...] Of course. I'm convinced Thera is the Lesser Colony and I believe it's the way in.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Nur-Ab-Sal: The woman that WAS is now THE KING THAT SHALL EVER BE! Address me accordingly, please.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Hermocrates: ...as the waters rose around their city, the Kings of Atlantis, one after another, sought to hold off fate. Knowing mortal men would never rule the sea, they planned a huge colossus, which by use of orichalcum, ten beads at a time, would make them like the gods themselves. Nur-Ab-Sal was one such king. He it was, say the wise men of Egypt, who first put men in the colossus, making many freaks of nature at times when the celestial spheres were well aligned.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

Indiana Jones: You know, a lot of my discoveries seem like tall tales, even to me. At least there's some evidence this time. Sophia Hapgood: Then again...maybe not... [...] What was that for? Indiana Jones: To ease the pain.

- Barwood, Hal (January 1991). "Afterword". Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. Dark Horse Comics, Inc (1): 28–29.

- Bevan, Mike (2008). "The Making of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Retro Gamer Magazine. Imagine Publishing Ltd. (51): 44–49.

- Piccalo, Gina (October 3, 2007). "'Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull': A primer". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- https://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comments/6a5v6m/im_noah_falstein_ive_been_making_games/dhbx8w1/

- Mishan, Eddie (October 10, 2004). "Interview with Hal Barwood". The Indy Experience. Archived from the original on November 8, 2005.

- "Hal Credits". Finite Arts. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: Developer Reflections". The International House of Mojo. Mixnmojo. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- Linkola, Joonas (August 31, 2000). "An Interview With Bill Eaken". LucasFans. Archived from the original on March 9, 2001.

- "Rising out of the SCUMM". Computer Gaming World. No. 87. Software Publishers Association. October 1991. pp. 32–34.

- "20th Anniversary". LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006.

- "About Us". LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Archived from the original on December 10, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "The Talkies Are Coming! The Talkies Are Coming!". The Adventurer. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (6). Spring 1993.

- Todd, Brett (June 22, 2009). "Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings Review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Back by Popular Demand, LOOM, The Dig, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, and Star Wars Battlefront II Headline List of Games Soon to be Available via Direct Download!". LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. July 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis on Steam". Steam Store. Valve. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (June 1992). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Scene: Atlantis.exe unknown flag input.

i: Interal [sic] Speaker; a: Adlib/SoundBlaster sounds; r: Roland sounds

- Lang, Jeffrey (1991). "Indiana Jones at Dark Horse" (PDF). Amazing Heroes. Fantagraphics Books Inc. (189): 28–33. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2011.

- "Just Review It: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Sega Visions. Infotainment World Inc. (December/January 1994): 58. 1994. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010.

- Reiss, Jo Ellen (Winter 1994–1995). The Adventurer. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (9). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lemon, Kim (July 2, 2004). "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: The Action Game". Lemon Amiga. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia & Lesser, Kirk (May 1993). "The Role of Computers". Dragon Magazine. TSR, Inc. (193): 60–61.

- Upchurch, David (January 1993). "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". The One Amiga (52): 54–57.

- Kennedy, Stevie (March 1993). "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Amiga Computing (58): 104, 105.

- Nuttal, Andy (February 1993). "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Amiga Format (43): 72, 73.

- Gill, Tony (January 1993). "Indiana Jones & the Fate of Atlantis". Commodore User: 48–51.

- Presley, Paul (September 1992). "Indiana Jones & the Fate of Atlantis Review". PC Review: 44.

- Smith, Rob (November 26, 2008). Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts. Chronicle Books. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8118-6184-7.

- Falstein, Noah (March 12, 2009). "Step 9; Include Structures that Adapt to Player Needs". In Bateman, Chris (ed.). Beyond Game Design: Nine Steps Towards Creating Better Videogames. Cengage Learning. pp. 227–229. ISBN 978-1584506713.

- LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC (April 22, 1993). Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Talkie Demo. LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

- Buchanan, Levi (May 20, 2008). "Top 10 Indiana Jones Games". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- Wee, Lim Choon (July 27, 1992). "The return of Indiana Jones". New Straits Times. p. 14.

- Ardai, Charles (September 1992). "The "Sea"quel; LucasArts' Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Computer Gaming World. No. 98. pp. 44–45.

- Ceccola, Russ (September 1992). "Indiana Jones & the Fate of Atlantis". QuestBusters. p. 1. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Ardai, Charles (September 1993). "Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Computer Gaming World. p. 86. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Invasion Of The Data Stashers". Computer Gaming World. April 1994. pp. 20–42.

- "CGW Salutes The Games of the Year". Computer Gaming World. November 1992. p. 110. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "The 7th International Computer Game Developers Conference". Computer Gaming World. July 1993. p. 34. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Staff (August 1994). "PC Gamer Top 40: The Best Games of All Time". PC Gamer US (3): 32–42.

- Staff (April 1994). "The PC Gamer Top 50 PC Games of All Time". PC Gamer UK (5): 43–56.

- Staff (November 1996). "150 Best (and 50 Worst) Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World (148): 63–65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 94, 98.

- AG Staff (December 30, 2011). "Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- The PC Gamer Editors (October 1998). "The 50 Best Games Ever". PC Gamer US. 5 (10): 86, 87, 89, 90, 92, 98, 101, 102, 109, 110, 113, 114, 117, 118, 125, 126, 129, 130.

- Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix 1 of 4: 1 (December 1, 1994), Dark Horse Comics, Inc

- Frank, Hans (July 18, 2007). "Interview: Hal Barwood". Adventure-Treff. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix #1 (of 4)". Dark Horse Comics, Inc. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix #4 (of 4)". Dark Horse Comics, Inc. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny #1 (of 4)". Dark Horse Comics, Inc. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny #4 (of 4)". Dark Horse Comics, Inc. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis |

- Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis at MobyGames

- Archive of Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix design documents from Aric Wilmunder - Design document, Cast, Room Design 1, 2, and 3