Intelligence dissemination management

It is a maxim of intelligence that intelligence agencies do not make policy, but advise policymakers. Nevertheless, with an increasingly fast pace of operations, intelligence analysts may suggest choices of actions, with some projection of consequences from each. Intelligence consumers and providers still struggle with the balance of what drives information flow. Dissemination is the part of the intelligence cycle that delivers products to consumers, and Intelligence Dissemination Management refers to the process that encompasses organizing the dissemination of the finished intelligence.

- This article is part of a series on intelligence cycle management, and deals with the dissemination of processed intelligence. For a hierarchical list of articles, see the intelligence cycle management hierarchy.

Intelligence information ranges from the equivalent of "we interrupt this television program" - to book-length studies which may, or may not, be read by policymakers. Large documents sometimes are legitimately for specialists only. Other lengthy studies may be long-term predictions. Recent worldwide events show that high-level policymakers simply do not read large studies, while staff briefers may.

In principle, intelligence is merely informational, and does not recommend policies. In practice, there are at least two specialized ways in which the effects of alternatives are considered. One is variously called a net assessment, correlation of forces analysis, or strategic assessment, and goes through comparisons of capabilities of both sides, and analyzing what the effects of various actions might be. The other is to use both information on one's own capabilities - and the best information on the others, and run realistic role-playing games or simulations, with people having senior policy experience either acting as the opposition, or possibly executing one's own role in a hypothetical situation.

Parameterizing

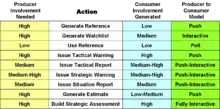

Dissemination and use decisions need to consider the nature of interaction between provider and consumer, and the special requirements of security.

Models

In logistics,[1] the two basic models are:

- push: the producer initiates the flow and the consumer receives it

- pull: the consumer requests or initiates the flow and the provider generates it.

Stating these as binary models, however, does not reflect the time factor. Drawing from business, another way of thinking about flow is the idea of just-in-time (JIT) inventory management, where a minimum of parts stays in a factory or store, with a closed loop between supplier and manufacturer/seller. Sellers keep the producers informed, in real time, of their inventory and consumption rate. Suppliers adjust the rate of production and the mix of products to keep an efficient logistic pipeline filled but not overflowing.

Push and pull, and JIT, models apply in intelligence as well, but are not always recognized as such. Logistical models, however, are simpler than certain cases of intelligence. Where the logistic model commands in one direction and receives in the other, some, but not all, forms of intelligence are interactive. To bring them together in a consistent model, consider, for a set of intelligence events:

- Intelligence producer activity

- Intelligence consumer activity

- Flow type caused by event

Intelligence has to be relevant. Assuming that some reference is considered to be useful, such as a basic country reference, users pull information from it when they have a question. There is relatively little interaction involved in producing the reference; analysts add to it when they have new material.

While analysts will do the basic work in developing indications and warning checklists, the analysts should get reality checks from the consumers. Where the analysts drive things, however, is when they issue warnings.

The issuance of a warning is almost always going to generate questions. A tactical report, however, may be enough, in and of itself, not to need more clarification, but to have the consumer take immediate action. Situation monitoring involves a steady flow of analyst actions, but there will be fairly frequent refinement requests from the consumers.

While analysts generate estimates, estimates may not be relevant unless consumers have been involved in defining the requirements for estimates.

Irrelevance is a related and arguably bigger problem for analysts than politicization. Intelligence analysis rarely impresses itself upon policymakers, who are inevitably busy and inundated with more demands on their time and attention than they can possibly meet. Intelligence officials must draw attention to their product and market their ideas. This is especially true in the case of any early-warning or intelligence-related development that has potentially significant consequences for important interests. A phone call, a personalized memorandum, a meeting-any and all are required if the situation is sufficiently serious. Involving relevant policymakers and other consumers in the regular personnel evaluations of the analysts who serve them would strengthen the importance of such an effort and provide an incentive to individual analysts

— CFR[2]

The proper relationship between intelligence gathering and policymaking sharply separates the two functions....Congress, not the administration, asked for the now-infamous October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iraq's unconventional weapons programs, although few members of Congress actually read it. (According to several congressional aides responsible for safeguarding the classified material, no more than six senators and only a handful of House members got beyond the five-page executive summary.) As the national intelligence officer for the Middle East, I was in charge of coordinating all of the intelligence community's assessments regarding Iraq; the first request I received from any administration policymaker for any such assessment was not until a year into the war

— P. Pillar[3]

Constraints

Many nations have an extremely restricted daily report that goes to the highest officials (e.g., the President's Daily Brief in the US), a more widely circulated daily that omits only the most sensitive source information, and a weekly summary at a lower classification level.

More generally than the classified equivalent of all-news channels, dissemination is the process of distribution of raw or finished intelligence to the consumers whose needs initiated the intelligence requirements.

Some parts of the intelligence community are reluctant to put their product onto even a classified web or wiki, due to concern that they cannot control dissemination once the material is in the published online format[4]

While modern information storage simplifies the handling and dissemination of exceptionally sensitive material, especially if it never is committed to hard copy, the systematic handling of compartmented information probably is most associated with the Special Liaison Units (SLU) originally for the distribution of British Ultra COMINT .[5] These units, and the equivalent US Special Security Offices (SSO), usually brought material to indoctrinated recipients, perhaps waited to answer questions, and took back the material. In some large headquarters, there was a special security reading room.

SLUs/SSOs had, from WWII on, dedicated, high-security communications links intended for their use alone. On occasion, senior commanders would send private messages over these channels.

Prior to US adoption of the British system, officer couriers brought COMINT to the White House and State Department, staying with the reader in most cases. For a time, after an intercept was found in the wastepaper basket of FDR's military aide, the Army and Navy cryptanalytic agencies unilaterally cut off White House access.[6]

In current US practice, there may be a special security office with the physical security of a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF) used for Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI) and Special Access Programs (SAP) information inside an organization. Parts of intelligence agencies, or manufacturing facilities for Special Access Projects, may, in their entirety, be considered secure for such material. Computer workstations with access to special security systems, if the overall building (e.g., CIA or NSA headquarters) is not approved for them, may be kept in the SCIF.

Soviet military intelligence rezidenturas in embassies had a central record room, from which individual GRU officers would check out locked file boxes, carry them to curtained alcoves, do their work, reseal the box, and check it back in.[7]

Dissemination of intelligence products

Basic intelligence

Consumers often need to look up individual facts. Increasingly, this material is in hyperlinked online documents, such as Intellipedia, which exists at the unclassified but for official use only, SECRET, and TS/SCI levels. Different agencies have different attitudes toward such publication; a resident consultant said that the CIA Directorate of Intelligence is uncomfortable with other than an Originator Controlled (ORCON) model,[4] while NSA seems more willing to let information flow among cleared users.

Warning and current intelligence

At a given level (e.g., alliance, country, multinational coalition, major military command, tactical operations), current intelligence centers continually provide customers, including other intelligence organization, with the all-source equivalent of daily newspapers and weekly newsmagazines. Current intelligence often is briefed directly to senior officers.

Current intelligence organizations need to be concerned with both tactical and strategic warning.[8]

The goal of tactical warning is to inform operational commanders of an event requiring immediate action. Warning of attacks is tactical, indicating that an opponent is not only preparing for war, but will attack in the near term.[9]

The goal of strategic warning is to prevent major surprises for policy officials.[8] Surprises, in part, manifest themselves in changes in the probability that some conceived-of event will take place, such that contingency plans are in place to respond to tactical warnings. A warning to national policymakers that a state or alliance intends war, or is on a course that substantially increases the risks of war and is taking steps to prepare for war, comes from:

- Attacks against the analyst's country and its interests, which can come from state or non-state actors, through military, terrorist, economic, information, and other means

- The breakdown of stability in an area or country critical to one's own side

- Key changes in adversary strategy and practice, especially with respect to terrorism or WMD proliferation attacks against the United States and its interests abroad by states and non-state actors via military, terrorist, and other means[9]

In combination, indications and warning (I&W)[9] provide alerts of potential or highly probable threat on the part of a hostile organizations. Indications may suggest preparation, such as an unusual pace of preventive maintenance, troop or supply transfers to shipping points, etc. Warnings are more immediate, such as the deployment of units, in combat formation, near national borders. Positive indications and warning may call for more specific "news reports" and briefings.

Countries with modern intelligence and operations communications networks can, on detecting indications and warnings, can initiate collaboration tools to help analysts share information. Specific actions, ranging from border crossings in large formations, to sorties of nuclear-capable ships and aircraft, to actual explosions, move at high priority on both operational and intelligence networks.

In the current environment of asymmetrical warfare by transnational groups, a given person dropping from sensors, or suddenly appearing outside their usual place, can be an indication of activity.

Tactical intelligence

According to the basic US Army manual on intelligence,[10] "Fundamental to decision-making in regard to any military operation is knowledge of the environment since it enables combatants to optimize the assets they have, to target their effort, to anticipate developments and husband their force." Current doctrine treats intelligence as "one of seven battlefield operating systems: intelligence, maneuver, fire support (FS), air defense, mobility/countermobility/survivability, combat service support (CSS), and command and control (C2) that enable commanders to build, employ, direct, and sustain combat power." Exercising the intelligence function produces information in several areas:

- Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (IPB). IPB helps the commander understand the current situation and its background.

- Situation development, which presents potential Enemy Courses of Action (ECOA) to the commander.

- Intelligence support to Force Protection (FP)

- Conduct police intelligence operations.

- At appropriate organizational levels, contribute to national intelligence through the Joint Military Intelligence Program (JMIP). Tactical Intelligence and Related Activities (TIARA) is the mirror image of military JMIP, providing direct support to warfighters

- With supporting intelligence units, synchronize intelligence development with surveillance and reconnaissance. The Operations Officer tasks the various units, with the Intelligence Officer defining objectives and analyzes the result.

- Manage distribution of national-level information (i.e., TENCAP, or Tactical Exploitation of National Capabilities), which may be Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI) or Special Access Programs (SAP). SCI and SAP need special access controls

"All these tasks take place within the dimensions of threat, political, unified action, land combat operations, information, and technology.

Starting with the basics: SALUTE

Standardization works very well for reporting, when it is drilled in from the beginning. The US Army has a new slogan, reinforced with video games, that "every soldier is a sensor." Standardized reporting for the most basic tactical things work under pressure, such as that which is defined by the acronym SALUTE, for a report about spotting the enemy:

- Size: how many men in the unit?

- Activity: what are they doing?

- Location: where are they? Give map coordinates if available, otherwise the best description available.

- Unit: who are they? Uniforms? Descriptions?

- Time: when did you see them?

- Equipment: what weapons do they have? Vehicles? Radios? Anything else distinctive?

Friction and standardization

With a trend toward multinational operations, there is even more opportunity for friction, when different doctrines (e.g., US intelligence cycle vs. NATO CCIRM) and restricted-to-own-nationals information become involved. US units, through TENCAP, are able to access national-level assets such as IMINT satellites, but rarely can share it with coalition partners.

For nuclear, biological, and chemical attacks, a CBRN Warning and Reporting System (CBRN WRS) is standardized among NATO countries and Australia. The basic reports are:

- CBRN 1-Initial report, used for passing basic data compiled at unit level.

- CBRN 2-Report used for passing evaluated data.

- CBRN 3-Report used for immediate warning of predicted contamination and hazard areas.

- CBRN 4-Report used for passing monitoring and survey results.

- CBRN 5-Report used for passing information on areas of actual contamination.

- CBRN 6-Report used for passing detailed information on chemical or biological attacks.

These reports, as are many such, are forms, with lines identified by letter. By text or by radio, one reads off letter codes, such as "CBRN 1. B(ravo) (my position). C(harlie) (direction of attack)" and so forth.

Beyond watch centers: Situation and interdisciplinary monitoring

As distinct from information needed for continuing tactical information, which often will come from organic or attached military intelligence units, national-level crises will need continuing and focused situation monitoring at the national or multinational level. To be able to establish situation-specific task forces or topical centers, there must be adequate basic intelligence, preassignments to task forces, and appropriate collaborative tools (e.g., Intellipedia) and basic intelligence.

Situation intelligence products need to be relevant to the level of reflection of the HQ making use of it: strategic (EU HQ, Operation Command HQ), operational (in-theatre force command HQ) or tactical (HQ deploying a force component in a local operation);

In some cases, the existing current intelligence, or indications & warnings, centers of national agencies may be adequate. The next step would be to set up conference calls or other collaborative techniques to link the relevant specialists in operations centers of different agencies, different countries, or perhaps multinational centers. These collaborations will produce periodic situation reports (SITREPS) to be disseminated to appropriate policymakers. It also disseminates other daily intelligence updates and products.

Longer range, more intractable intelligence challenges are addressed by grouping analytic and operational personnel from concerned agencies into close-knit functional units. Examples at both the national and multinational levels include counterterrorism (e.g., Singapore counterterrorism and ASEAN counterterrorism training center, transnational crime and drug enforcements (e.g., Interpol) and verification of compliance with nonproliferation treaties (e.g., Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO, to be established)).

Estimates

Estimates are coordinated analyses, by the intelligence community at the national levels, or by the various intelligence staff sections at a command level, of the various courses of action available to an actor of interest, and the likelihood of each. Estimates primarily consider the unilateral actions of the other side, or its actions in response to a well-defined actions of one's own side. Estimates are not strategic assessments, which examine a broader scope of strengths and weaknesses between one's side and that of another.

Most countries with a well-developed system of estimates have different types, with different time scales, and representing either an intelligence community consensus, or possibly an ideologically oriented group that justifies a premade conclusion.

In the US, National Intelligence Estimates are detailed analyses, typically in the tens to hundreds of pages, produced once a reasonable consensus is reached. These documents may contain dissenting footnotes, also called reclamas, documenting a disagreement by a particular organization or specialists. NIEs are typically associated with standing task groups. Special National Intelligence Estimates (SNIE) are short-term community documents, in response to a specific customer requirement.

There is controversy over the US Office of Special Plans and whether it bypassed the intelligence community cross-checking process. Winston Churchill had his own intelligence advisor, Sir Desmond Morton, who might bypass the WWII estimative process.

Estimative intelligence helps policymakers to think strategically about long-term threats by discussing the implications of a range of possible outcomes and alternative scenarios. They are not strictly operational, but fall into a special analysis and dissemination category because they usually involve multi-agency coordination.

In the topmost article of this series, Sun Tzu was quoted .[11] The Griffiths translation does speak of "estimates", but, according to Pillsbury,[12] a new translation from the Chinese Academy of Military Science argues that Griffiths mistranslated: "strategic assessments" is more accurate than "estimates".[13]

Between intelligence and action

Going beyond the pure intelligence is the assessment of known capabilities of one's own resources versus the best estimate of opponent capabilities.

Clausewitz' book On War[14] asks a simple question: How can the national leadership know how much force will be necessary to bring to bear against a potential enemy? Clausewitz replies, "We must gauge the character of . . . (the enemy) government and people and do the same in regard to our own. Finally, we must evaluate the political sympathies of other states and the effect the war may have on them.

Clausewitz warns that studying enemy weaknesses without considering one's own capacity to take advantage of those weaknesses is a mistake.

Many first heard of the term centers of gravity in the context of Desert Storm or COL John Warden, but Warden's contribution was adapting the idea [15] to air campaigns, of the Clausewitz idea[14] of a "center of gravity," a feature that if successfully attacked, can stop the enemy's war effort. Assessment requires considering the potential interaction of the two sides. According to Clausewitz, "One must keep the dominant characteristics of both belligerents in mind."

Net assessment

First and foremost, Net Assessment is nothing but the capability to analyse and measure the strategical assets of each warring side (for example, how many tanks it has, how many soldiers etc.). But Net Assessment is not only the measurement of material matters, but it is also the capability to try to estimate moral assets such as a people's will to fight in a given war, how far a state is capable of waging war, how willing are their generals and soldiers to fight in a war and other moral aspects of warfare in general. In the US, strategic assessment is one step beyond intelligence estimates, although intelligence analysts may well participate in the subsequent process of strategic assessment. The result, called a net assessment in the US and the correlation of forces in the fUSSR, are not themselves contingency plans, but are critical to the formulation of plans. Strategic assessment, above all else, is an examination of interactions, rather than the likely unilateral actions of another side or coalition.

Formalizing the role of a command historian was one of the first steps in the evolution of a true general staff,[16] as opposed to the personal entourage of a commander. By applying the planned assessment methodology to historical data, the methodology, cautiously, may be validated. Caution is needed because contingencies can make historical behavior obsolete.

In fact, a widely praised explanation for the causes of war is precisely that strategic assessments were in conflict prior to the initiation of combat—one side seldom starts a war knowing in advance it will lose. [17] Thus, we may presume there are almost always miscalculations in strategic assessments of varying types according to the nature of the national leadership that made the assessment.[12]

How not to do net assessment

How have major nations conducted strategic assessments of the security environment? There is no one standard. There are some errors that repeat. The Office of Net Assessment, in the US Department of Defense, under Andrew Marshall, commissioned a set of seven historical examples of strategic assessment from 1938 to 1940,[12] compares the pre-WWII equivalent of net assessment by seven countries. Mistakes in these assessments become "lessons learned" are relevant to any effort, Pillsbury's focus, to understand how the Chinese leadership conducts strategic assessment of its future security environment.

In his specification for the study, Marshall specified four motivations for assessment:

- Foreseeing potential conflicts

- Comparing strengths and predicting outcomes in given contingencies

- Monitoring current developments and being alerted to developing problems

- Warning of imminent military danger.

The main problem was how to frame assessments, particularly with regard to political-military factors such as who were the potential threats and potential allies, and what international alignments would be vital to the outcomes of future wars.

Simplistic force ratios and assumptions

An early but obsolete approach to estimation was a very simple quantitative one, using Lanchester's Laws. A simple comparison of forces of roughly equal capability can come down to number of soldiers, ratio of attackers to defenders, defensive quality of the terrain, and other basics. That sort of model breaks down, however, when the forces are dissimilar in quality of leadership, troop morale and initiative, or doctrine and technology. Japan made this mistake as it prepared for WWII, putting garrisons on a large number of islands, and considering their battleships one of their centers of gravity.

Japan's early WWII strategy towards the US, for example, made numerous assumptions that would lead the US Fleet to sail into the Western Pacific, to fight, on advantageous terms for the Japanese, a "Decisive Battle". Unfortunately for the Japanese, the US did not choose to make battleships its primary arm, fight for every Japanese outpost, use submarines only against the warrior targets of warships, or require a return to a fleet anchorage for regrouping. Intelligence was not a preferred assignment in the Japanese military, and their operations planners tended to make optimistic assumptions. An eccentric but incredibly creative US Marine, Earl Ellis, however, did foresee the US strategy for the Pacific in the 1920s, and set a standard for long-term estimates and net assessment[18]

France, as well as Japan, used overly simplistic assumptions and calculations in assessing the 1939 situation with Germany. Army manpower and equipment were roughly equal, with a slight advantage to France. French tanks, individually, were superior in weapons and protection to their German equivalent. German air power, however, was nearly double that of France. At its highest governmental levels, France did not understand the way in which Germany would combine tanks and aircraft, closely coordinated, and drive quickly into the rear, with German infantry securing the breaches. Ironically, a fairly junior officer, named Charles de Gaulle, had described just such tactics as Heinz Guderian conceived in Blitzkrieg.

In the areas of breakthrough, the Germans achieved at least a 4:1 advantage by not advancing on a broad front. Numeric ratios alone, as in the Lanchester equations, could not deal with concentration of force, or the force multiplier effect of coordinated air and armor. France also failed to consider that Germany might first defeat East European allies such as Poland and Czechoslovakia. The lesson for intelligence here is not to assume a very limited range of allies, or that certain avenues of attack, such as the Germans through the Ardennes or the Low Countries, are impossible. The analyst has the responsibility to let consumers, who may be subject matter experts, know about unlikely scenarios, as well as giving the consumers the detail they want on the likely scenarios.

Psychological and diplomatic assumptions

Another mistake is to assume which nations and groups will see the country doing an assessment as a friend. In planning for WWII, the United States developed the "Rainbow Series" of war plans; the serious assumption was that Japan would be the only significant enemy. While this was wargamed again and again, there had been little analysis of a two-front war with the Axis.

For WWII, Britain had assumed France would be an effective ally, rather than quickly defeated. Britain also did not consider the effect of the Soviet Union as a second front. This was understandable given the initial Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact before Germany attacked the USSR, but forced the reevaluation of the European balance of power.

Not all WWII assumptions were flawed. The USSR assumed Japanese neutrality toward the Soviets, which was, indeed, the case until the USSR declared war at the very end of WWII.

In 1990–1991, while the US had assumed it would be able to base troops in Saudi Arabia to meet a threat to that nation, such as the invasion of Kuwait, that was not a prior commitment by the Saudis. Even when preliminary negotiations were positive, the size of the proposed American force shocked the Saudis. For a time, until the King was convinced, the US assumption was just that.[19]

Iraqis did not greet American troops with flowers in 2003.

Assumptions about opposing decisionmaking

Robert S. McNamara, US Secretary of Defense during most of the Vietnam War, came from a background of quantitative analysis both in conventional warfare and industry, but appeared to assume that the North Vietnamese leadership would use logic similar to his own.[20] Lyndon B. Johnson, however, personalized conflict, seeing Ho Chi Minh as someone to dominate. Both assumptions were severely flawed.[21] Intelligence analysts need to estimate on what is known about the opposition, not what one's own leadership would like them to be. Unfortunately, as McMaster points out, Johnson and McNamara tended to ignore intelligence that contradicted their preconceptions.

Assumptions about doctrine and capabilities

It can be dangerous to assume wartime capabilities of an opponent, based on their published doctrines, known training exercises, deployments, and news reporting. There was widespread belief that some of the key US weapons systems, such as the M1A1 Abrams tank, AH-64 Apache helicopter, stealth technology and precision guided munitions would not be effective in the deserts of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq. While detailed postwar analysis showed that early reports about weapons effectiveness were overstated, precision guidance was a significant force multiplier. An unexpected force multiplier was GPS, which let Coalition soldiers go off-road and move through the desert as ships moved through the seas, where Iraqis stayed on roads for ease of navigation.[19]

Performing strategic assumptions

What goes into strategic assessment? A RAND Corporation study[22] starts with assessing national power, based on resources, the nation's ability to use those resources, and the capabilities of both its standing military and how that military could be multiplied by national mobilization.

This study, however, was focused on conventional warfare, and did not consider the much more common national military and nonmilitary options other than war. The latter, variously known as nation-building, peace operations,[23][24] or stability operations[25]

While many of his ideas are controversial, Thomas P.M. Barnett created a paradigm that better combines the military and nonmilitary aspects. His fundamental model says "The problem with most discussion of globalization is that too many experts treat it as a binary outcome: Either it is great and sweeping the planet, or it is horrid and failing humanity everywhere. Neither view really works, because globalization as a historical process is simply too big and too complex for such summary judgments. Instead, this new world must be defined by where globalization has truly taken root and where it has not.

"Show me where globalization is thick with network connectivity, financial transactions, liberal media flows, and collective security, and I will show you regions featuring stable governments, rising standards of living, and more deaths by suicide than murder. These parts of the world I call the Functioning Core, or Core. But show me where globalization is thinning or just plain absent, and I will show you regions plagued by politically repressive regimes, widespread poverty and disease, routine mass murder, and—most important—the chronic conflicts that incubate the next generation of global terrorists. These parts of the world I call the Non-Integrating Gap, or Gap".[26] Barnett states the approach as creating two forces, "Leviathan" (a term from Thomas Hobbes) and "System Administrator".[27]

The system administrator force focuses on connecting nations to the "Core". Typically, it would be a multinational organization, not primarily a military force although containing police and security forces, and having regular military force available. "Leviathan" would be a "First World", network-centric combat force that can take down the conventional military of almost any nation. While Barnett's arguments that the 2003 invasion of Iraq are questionable in hindsight, one can also observe that the invasion used Leviathan alone, and an outcome might have been different had a System Administrator force been following Leviathan, with adequate resources and legitimacy.

US contemporary

In the broadest definition, "strategic assessment" implies a forecast of peacetime and wartime competition between two nations or two alliances that includes the identification of enemy vulnerabilities and weaknesses in comparison to the strengths and advantages of one's own side. Many lessons have been learned, including perspective on balancing security of information against use of information. In the 1950s, RAND Corporation analysts who were doing the studies of Soviet power for the Defense Department, was producing badly skewed results, based on the Soviets being more dangerous than they were in reality. The analysts were not allowed to know, for security reasons, that Soviet Bison and Bear bombers had critical reliability problems. More bombers might crash in the Arctic than could arrive in North America .[28] US strategies, therefore, were less risk-taking. When the senior commanders and the intelligence community eventually found out the effects of the disconnect, it led to some reexamination of the tradeoffs between having absolutely secure intelligence versus intelligence that could actually affect policy.[28]

The practice of strategic assessment by the U.S. Department of Defense in the past 25 years has been divided into six categories of studies and analysis:[12]

National/Multinational military balance

"Measure and forecast trends in various military balances, such as the maritime balance, the Northeast Asian balance, the power-projection balance, the strategic nuclear balance, the Sino-Soviet military balance, and the European military balance between NATO and the former Warsaw Pact. Some of these studies look 20 or 30 years into the future to examine trends and discontinuities in technology, economic indicators, and other factors."

Weapons and force comparisons

"Weapons and force comparisons, with efforts to produce judgments about military effectiveness that sometimes "revealed U.S. and Soviet differences in measuring combat effectiveness and often showed the contrast between what each side considered important in combat."

Validation

"validation examines lessons of the past using historical evaluations as well as gathering data on past performance of weapons used in the context of specific conflicts.

Red Team

Red Team perceptions of foreign decision makers and even the process by which foreign institutions make strategic assessments. As Andrew Marshall, Director, Net Assessment, wrote in 1982 about assessing the former Soviet Union, "A major component of any assessment of the adequacy of the strategic balance should be our best approximation of a Soviet-style assessment of the strategic balance. But this must not be the standard U.S. calculations done with slightly different assumptions . . . . rather it should be, to the extent possible, an assessment structured as the Soviet would structure it, using those scenarios they see as most likely and their criteria and ways of measuring outcomes . . . the Soviet calculations are likely to make different assumptions about scenarios and objectives, focus attention upon different variables, include both long-range and theater forces (conventional as well as nuclear), and may at the technical assessment level, perform different calculations, use different measures of effectiveness, and perhaps use different assessment processes and methods. The result is that Soviet assessments may substantially differ from American assessments. Studies analyzing perceptions are difficult because the data used often must be inferred from public writings and speeches. Implicit biases of Americans based on our own education and culture must also be avoided."

Tool research

- Search for new analytical tools, such as developing higher "firepower scores" than may be used for the Air Force and Navy as well as the initial inventor, the ground forces. In the early 1980s, a multiyear effort was funded at The RAND Corporation to develop a Strategy Assessment System (RSAS) as a flexible analytic device for examining combat outcomes of alternative scenarios.

Assessing alternatives

- Professional analyses of particular issues of concern to the Secretary of Defense that may involve identifying competitive advantages and distinctive competencies of each size military force posture; highlighting important trends that may change a long-term balance; identifying future opportunities and risks in the military competition; and appraising the strengths and weaknesses of U.S. forces in light of long-term shifts in the security environment. Past practitioners from the Office of the Secretary of Defense have underscored the need for American strategic assessment to focus on long-term historical patterns rather than on

Russian contemporary

The most relevant comparison for China may be the Soviet Union, but this is also the most secret. As Professor Earl Ziemke put it, after three decades of research on Soviet military affairs, even when he tried to use historical data to look back from 1990 to 1940:

The Soviet net assessment process cannot be directly observed. Like a dark object in outer space, its probable nature can be discerned only from interactions with visible surroundings. Fortunately, its rigidly secret environment has been somewhat subject to countervailing conditions. . . . Tukhachevsky and his associates conducted relatively open discussion in print.[29]

Chinese Contemporary

There is intense secrecy about Chinese national security matters, but comparisons with other nations' processes of strategic assessment can increase our understanding of how China may assess its future security environment. By viewing China in comparative perspective, it may be possible to understand better how China deals with its assessment problems.[29]

"Comparing the Soviet structure with Chinese materials in the 1990s, it is apparent from the way in which Soviet strategic assessment was performed in the 1930s that a number of similarities, at least in institutional roles and the vocabulary of Marxism-Leninism, can also be seen in contemporary China. The leader of the Communist Party publicly presented a global strategic assessment to periodic Communist Party Congresses. The authors of the military portions of the assessment came from two institutions that have counterparts in Beijing today and were prominent in Moscow in the 1930s: the General Staff Academy and the National War College.

Another similarity was that the Communist Party leader chaired a defense council or main military committee and in these capacities attended peacetime military exercises and was involved deciding the details of military strategy, weapons acquisition, and war planning.[29]

In the US, there are independent or ideologically associated "think tanks", and there are government contract research organizations both not-for-profit and for-profit. In China, the primary difference between these Chinese institutes and American research institutes is their "ownership." Research institutes are "owned" by the major institutional players in the national security decision making process in China. Members of these institutes often decline to discuss in any detail the exact nature of their internal reports. They are not puppets, however, and many research institutions are important in their own right for the creative ideas they produce. Their leaders carry great prestige and have high rank in the Communist Party.[29]

Strategic gaming

Gaming, when it involves players that have experience at the levels at which they are playing, can complement or validate strategic assessment.[30] This section is not intended to be a general discussion of strategic gaming, but to address the role that intelligence material will play in constructing and playing the game. It is not uncommon, at national levels, to have intelligence analysts in the "Red Force" or other nations in a multilateral game, play their counterpart or an equivalent commander in the country or group on which they are expert.

Participation by top-level policymakers

Even at national-level games, it has always been the US practice never to have the incumbent President as an actual player, although some have observed. The rationale is preventing any adversary from knowing, with high confidence, how a President will decide in a given circumstance. The Presidential player typically is a former Cabinet member with extensive politicomilitary experience.

Britain, however, may regard top-level games as a valuable practice exercise for policymakers. Margaret Thatcher was reputed to play in these games, and be very serious about them.

Warfighter and battle labs

Strategic gaming is to be distinguished from training exercises, although there are training exercises for generals at the division (two-star) and corps (three-star) levels. As opposed to the battalion and brigade level troop exercises at the National Training Center (heavy/armored forces, Ft. Irwin, CA) and light forces at Joint Readiness Training Center (light forces, Ft. Polk, VA), what are now called Warfighter (formerly BCTP) exercises are apt to be command posts only, with controllers simulating subordinate units. This is realistic, as in modern warfare, the forces are so widely dispersed that senior generals could not physically watch all their forces. As a result of the "command post in the sky" excesses of Vietnam, with stacked helicopters well up the chain of command, micromanaging small battles, there is a reluctance to let generals get too close.

Cold War gaming

During the Cold War when major nuclear exchanges were a real possibility, the two sides understood one another reasonably well. Over time, even more so after the end of the USSR, Russia and the US have taken various steps to avoid military misunderstanding, such as putting liaison teams into one another's' strategic warning centers.

In the beginning of the Cold War, strategic gaming, given the "massive retaliation" strategies of the earlier parts of the Cold War, concentrated on major nuclear exchanges. One of the things taught by these games was that the resultant exchanges would cause huge casualties, but might not be politically meaningful. It can be argued that war gaming results were an incentive, in the late fifties and early sixties, to bring nuclear targeting under tighter civilian policy control in the US, and start to explore more limited scenarios such as counterforce, counterforce with avoidance[31] and "blunting" conventional forces. Tactical nuclear warfare limited to the oceans was examined as an option that might not escalate. The actual gaming, however, appeared to disprove some assumptions based on simple force ratios. Originally, the GLOBAL series of naval wargames assumed that the US Mediterranean fleet would be obliterated in hours, and the Soviet submarine threat would stop major transatlantic movement by US forces. Especially with cooperation from other services, these assumptions were not found to be consistently true. A side effect of learning how interdependence could help all services was improved cooperation among the military intelligence and operations personnel.

Scenarios began to be explored that involved conventional warfare between the US and USSR, and proxy war.

As important as the joint, interactive nature of the game was, GLOBAL increasingly was recognized for the realism injected into the decisionmaking that represented what might be expected in a global superpower military confrontation. Also significant in these early games was an evolution of offensive strategies on the part of the "Blue" force as the players began to appreciate the survivability of forward-engaged maritime forces and the synergistic contributions of joint and combined forces. Equally revealing was the shift over time to an outcome that favored conventional rather than nuclear escalation, and the opinion that US and NATO forces would ultimately emerge victorious from a conventional war of extended duration once the economic capacities of the West had shifted to military production. Issues of particular interest provided the foundation for the iterative process of "game-study-game." They included the following:

- The absolute necessity for the prompt use of strategic warning

- The requirement to examine military strategies for protracted conventional war

- The need to explore the longer-term effects of horizontal escalation

- The benefits of early identification of technological needs

"One of the reasons for this favorable appraisal [of GLOBAL] was the growing involvement of the military services and relevant civilian agencies of the federal government in a common forum. Another was the opportunity to challenge conventional wisdom by imposing real-world constraints on untested theories. "Finally, this sorting out of the conventional from the game-tested wisdom helped the players, in the real world after the exercise was over, to focus on the pertinent second-order issues.

The games were educational for the intelligence community, in learning the sort of information that policymakers needed in a critical situation, in understanding the information that needed to be researched even to create a plausible scenario. Policymakers and senior commanders learned how to use intelligence more effectively, and how to make use of the community resources. They also provided an opportunity to test new strategies and tactics, and sometimes explore the potential of weapons systems under consideration."[32]

Contemporary gaming: the 1920s in a new version?

"Andy Marshall, the Director of Net Assessment in the Pentagon and a notable consumer of wargaming, has argued that the circumstances facing the United States today, in terms of strategic uncertainty, are quite similar to those we confronted in the early 1920s. The beginning of that interwar period saw the emergence of new technologies with startling potential military applications." Threats were unclear, although Japan was seen as the likely enemy. It must be remembered that no intelligence community existed at the time. Can the modern intelligence community establish ways to test a wide range of opponents in a context of a "system of systems"?[33] Between the World Wars, games tended to be service specific. One service's intelligence was unlikely to consult with another, so the interactions of land-based aircraft, other than naval aviation, might not be considered. The British also did such games, yet Churchill described, in his history of WWII, that the Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse was his greatest shock of the war.

Perhaps because the Navy was more used to map exercises than the Army, the Naval War College was able to develop new concepts through gaming. Part of this was defining the requirements "for a measured, step-by-step offensive campaign, and began to appreciate the potential of naval aviation to operate as a principal offensive system, rather than as a "scouting arm," for the main battle fleet." The aviators were both providers of intelligence as scouts, and consumers of intelligence for strike planning.

What trends appear to be emerging from contemporary wargaming that can help shape our (significantly downsized) armed forces for the next century, as well as planning the intelligence community to meet the warfighters' needs? What are the lessons we have learned and where are the lessons to be learned? Priorities, all intelligence-dependent, seem to include: surveillance and precision strike capabilities, information technology and warfare, advanced battle management, and mutually supportive assets, the latter including military and national intelligence.

Surveillance and precision strike capabilities

Post Cold War games at the Naval War College indicated that aircraft carriers had to be faster than cruisers in order to survive. Similar survival-type games are needed to test current and planned precision strike platforms and systems, such as the survival of carrier battle groups in the littoral, a comparison of carrier battle groups with future surface combatant concepts, and the range and stealthiness required for carrier-based aircraft to prove effective and survivable. Attention must be paid to the survivability of intelligence cycle components, from sensors to dissemination, and what happens when they are degraded.

From the first Army AAN wargame, the essential role of space in C3I and ISR was apparent. Intelligence collection caspabilities were considered early in the planning process, not as an afterthought. The criticality of space systems was such that intelligence needed to determine the threat to them, and then develop alternatives (e.g., UAVs) if the space-based systems are disabled. These space-based systems are not limited to pure intelligence; consider the dependence of both fighting and intelligence functions on GPS. Recognizing that criticality is one reason that complementary, terrestrial eLORAN is attracting interest.

Tight coupling of sensors and precision attack might shift frameworks to a "halting" rather than a "buildup" or "counterattack" framework. Gaming can explore the intelligence requirements to know what are the centers of gravity for halting frameworks.

Information technology and warfare

Current games, especially when using actual C3I equipment, are exploring the amounts of intelligence information that may flow, and the communications support that will be needed. games and cases point to the importance of developing visions of future conflict, and working them to discern how changes in the external environment could cause the next war to differ from the last. Experience in Kosovo demonstrated friction when adequate intelligence management was deployed early, and friction in Bosnia when it was not. Wargames now need to explore the effects of portions of one's own, or one's opponent, C3I and ISR capabilities being disabled.

In the 1930s, naval officers began to understand the need for task force organization. Games have to explore the interoperability of intelligence systems for ad hoc, interservice task forces. There is a need to understand what happens if the opponent has comparably sophisticated organizational flexibility, C3I, and ISR.

Are the services anticipating the changing nature of future conflict in their wargaming? Are the experiences from those wargames enriching or challenging the services' vision? Are the lessons learned in the wargames played by the separate services being transferred into the joint arena? In other words, when it comes to wargames, who's winning and who's losing.[33]

Major games

The major games, authorized by explicit Congressional funding, all taught lessons, including that the services were not starting from a terribly coherent future picture. Services reached a bit less into the future, and made significant changes to their doctrinal frameworks.

This process was especially informational to military intelligence producers and consumers, as well as to the analysts concerned with technological development and where and when to focus.

US Navy: GLOBAL

Played between 1979 and 1990, the games during the Cold War contributed to the "Maritime Strategy" doctrinal framework for forward engagements of the Soviets. After the fall of the USSR, however, the threat became more diffuse and the games were criticized.

They led to the new framework "From the Sea", associated with intelligence-intensive "network-centric warfare". Again, both intelligence and operations people learned more about each other's needs and capabilities.

US Army: Army After Next/Transformation Wargame

Beginning in 1997 the Army's Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) began annual "Army After Next" (AAN) games—the AAN being viewed as what the presently planned "digitized" Army (Force XXI) would interact with a strong enemy in the year 2020. One surprising result was that air and naval fire support might be more flexible than the traditional organic artillery, although the role of precision guidance for organic fire support became even more obvious to the Army and Marines. This fire support, however, was dependent on space-based C3I, as well as a much greater Army ISR capability and networking all of these into a "system of systems" Some findings included:

- The strong influence of space-based systems on ground combat operations

- The vulnerability of ground forces to information warfare attacks

- A reluctance on the part of national leaders to commit ground troops to a region early in a crisis

- Dramatically shortened time frames in which critical decisions had to be made[32]

Early AAN results led to opposition from senior leaders, who regarded their comments as reality checks. Some senior officers suggested that using technologies from 20 years in the future was the equivalent of introducing supersonic aircraft into a 1920 wargame, not completely unreasonable given the exponential rate of technology improvement. The 20 year target, and the associated "History of the Future" document, was intended to allow examination of concepts without worry about budget, but the interaction between leadership and gamers educated all in what was realistic. This lesson might be quite important for intelligence personnel doing longer-term estimates. As a result, the AAN wargame has been restructured to forecast a 10- to 15-year future and, in 2000, the name of the series was changed to the Transformation wargame.

Both the games and real-world Army experience has taught that simply calling something "transformational" will not make it so, and tough testing, in games as well as battle laboratories, is essential.. The Army had to experience intelligence problems in Kosovo before it could define the problem well enough to include it in games.

AAN were not intended to be forecasts, but a way to test concepts. "By repeating the games, the plan was to conduct comparative analysis as scenarios and adversaries varied over the long term. In this case, however, it appears that a confrontation with an unpleasant present, rather than the repetitive pull of a coherent vision of the future, was the catalyst providing new direction for Army planning and wargaming.[33]

US Air Force: Global engagement/aerospace future capabilities

Air Force experience, early in the gaming process, revealed, as with the other services, a need for a more coherent concept of future challenges. As with the other services, a new doctrinal framework evolved, the Air Force version being "Expeditionary Air Forces," therefore, was essential in giving the games purpose and substance.

Expeditionary Air Forces involve new mixed units of different aircraft types, but are not as disruptive as early frameworks that assumed extensive use of space-based systems, UAVs, and extremely long-range operations. Just as the Army found looking forward 20 years was unrealistic, the Air Force reexamined the chances of revolutionary assets being affordable and implemented in a more modest future. The intelligence community could give them options of potential opponents' vulnerabilities, so the games helped focus attention on the most critical of the disruptive technologies. In turn, the intelligence community learned much more about what aggressive air warfare needed from them.

Millennium Challenge 2002

While this game generated considerable political controversy, it is being mentioned here as a reminder of how asymmetrical modern conflict can be, and the challenges that asymmetric thinking can present to intelligence capabilities and assumptions. LTG Paul K. Van Riper, USMC (ret.) commanded the enemy military in a Gulf scenario. According to Robert B. Oakley, ambassador and later special envoy to Somalia, who played the Red civilian leader, Van Riper was "out-thinking" Blue Force from the first day of the exercise. He also maneuvered Red forces frequently, potentially defeating non-real-time IMINT.

A relevant point to this discussion was that by using motorcycle messengers, he neutralized Blue COMINT capabilities. While it obviously will not be discussed in the open literature, a serious question arises of how dependent a Blue network-centric force is on its SIGINT capability against the other side. If they operate under strict radio silence (i.e., EMCON), will other intelligence collection systems take up the slack? This is not a question only for the US, since other major powers may find themselves in asymmetric conflicts, but without as many other sensors as the US, especially space-based ones that are probably immune from attack by a low-technology opponent.

Van Riper, in a leaked email, said "Instead of a free-play, two-sided game … it simply became a scripted exercise." The conduct of the game did not allow "for the concepts of rapid decisive operations, effects-based operations, or operational net assessment to be properly assessed. … It was in actuality an exercise that was almost entirely scripted to ensure a Blue 'win.' "

At one point in the game, when Blue's fleet entered the Persian Gulf, he sank some of the ships with suicide-bombers in speed boats. At various times in their separate war games before WWII, the US and Japanese navies "refloated" certain ships, which apparently was done in Millennium Challenge. "Exercise officials denied him the opportunity to use his own tactics and ideas against Blue, and on several occasions directed [Red Force] not to use certain weapons systems against Blue. It even ordered him to reveal the location of Red units." One of the priority areas for US military research is littoral. [34] While existing shipboard and possibly airborne radars might not have detected the speedboats, there is work in wake detection with MASINT sensors that might have picked up the boats. Was such a sensor capability being assumed? If there is such a sensor, it would be likely to be highly classified.

Without exact knowledge of what happened, the situation is not as clear as either side might have it. In the Louisiana Maneuvers of 1940, George S. Patton moved an armored division with unprecedented speed, eventually capturing the commander of the opposing army, Ben Lear. Lear was "repatriated", in the sense that there were many tactical ideas that Lear's army was to test for overall US knowledge. While Patton's act was dramatic, it disrupted some of the tests for which the exercise was being run. In Van Riper's case, were there things that his actions prevented from being tested, or was he demonstrating US weaknesses that the political level did not want known?

In his email about quitting the game, "You don't come to a conclusion beforehand and then work your way to that conclusion. You see how the thing plays out." He added, somewhat ominously in retrospect, "My main concern was we'd see future forces trying to use these things when they've never been properly grounded in any sort of an experiment."

Finally, the paper quoted a retired Army officer who has played in several war games with Van Riper. "What he's done is, he's made himself an expert in playing Red, and he's real obnoxious about it," the officer said. "He will insist on being able to play Red as freely as possible and as imaginatively and creatively, within the bounds of the framework of the game and the technology horizons and all that, as possible. He can be a real pain in the ass, but that's good. … He's a great patriot and he's doing all those things for the right reasons."[35]

References

- Edwards, John E. (2004). Combat Service Support Guide, 4th Edition. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3155-3.

- Council on Foreign Relations (1996). "Making Intelligence Smarter: The Future of US Intelligence". Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- Pillar, Paul R. (March–April 2006). "Intelligence, Policy, and the War in Iraq". Archived from the original on 2007-11-10. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- Berkowitz, Bruce. "The DI and "IT": Failing to Keep Up With the Information Revolution". Studies in Intelligence. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- Winterbotham, F.W. (1974). The Ultra Secret. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-76832-8.

- Kahn, David (1996). The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing. Scribners. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- Suvorov, Viktor (1987). Inside the Aquarium. Berkley. ISBN 0-425-09474-X.

- Davis, Jack (September 2002). "Improving CIA Analytic Performance: Strategic Warning" (PDF). Occasional Papers, The Sherman Kent Center for Intelligence Analysis, (US) Central Intelligence Agency. 1. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- US Department of Defense (12 July 2007). "Joint Publication 1-02 Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- US Department of the Army (2004). "Field Manual 2-0, Intelligence" (PDF). FM 2-0.

- Sun Tzu (1963). The Art of War (translated by Samuel B. Griffiths). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-501540-1.

- Pillsbury, Michael (January 2000). "China Debates the Future Security Environment, Appendix 1: The Definition of Strategic Assessment". National Defense University Press. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- Pan Jiabin and Liu Ruixiang (1993). Art of War: A Chinese-English Bilingual Reader. Junshi kexue chubanshe.

- Wikisource:On War#On the nature of war .28Book I.29

- Warden, John A. III (1988). "The Air Campaign: Planning for Combat". National Defense University Press. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- Goerlitz, Walter (1975). History of the German General Staff, 1657-1945. reenwood Press Reprint. ISBN 0-8371-8092-9.

- Ikle, Fred C. (2005). Every War Must End. Columbia University Press.

- Ellis, Earl H. (23 July 1921). "Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia". Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- Schwarzkopf, H Norman Jr. (1993). It Doesn't Take a Hero. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-56338-6. Schwarzkopf 1993.

- McNamara, Robert S. (1997). In Retrospect. Random House. ISBN 0-517-19334-5.

- McMaster, H.R. (1997). Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-018795-6.

- Tellis, Ashley J.; et al. (2000). "Measuring National Power in the Postindustrial Age: Analyst's Handbook" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- "Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations". 2000. Archived from the original on 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- "Future of Peace Operations Program". 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- Dicker, Paul F. (July 2004). "Effectiveness of Stability Operations during the initial Implementation of the Transition Phase for Operation Iraqi Freedom" (PDF). Army War College. USAWC. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- Barnett, Thomas P.M. (2003). "Esquire interview on The Pentagon's New Map". Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- Barnett, Thomas P.M. (2004). The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century. Putnam.

- Bracken, Paul (Spring 2006). "Net Assessment: A Practical Guide". Parameters. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- Pillsbury

- Caffrey, Matthew. "Toward a History Based Doctrine for Wargaming". Air & Space Power Journal.

- Herman, Kahn (1986). On Escalation: Metaphors and Scenarios. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25163-0.

- Haffa, Robert P.; Patton, James H. Jr. (Spring 1998). "Gaming the "System of Systems"". Parameters. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- Haffa, Robert P.; Patton, James H. Jr. (Spring 2001). "Wargames: Winning and Losing". Parameters. USAWC-Haffa-2001. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- National Academy of Sciences Commission on Geosciences, Environment and Resources (CGER) (April 29 – May 2, 1991). "Chapter 9: Measurement and Signals Intelligence". Symposium on Naval Warfare and Coastal Oceanography. Naval Amphibious Base, Little Creek, Virginia: National Academies Press. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- Fred Kaplan (March 28, 2003). "War-Gamed: Why the Army shouldn't be so surprised by Saddam's moves". Slate. Retrieved 2007-10-30.