Iqbal Masih

Iqbal Masih (Urdu: اقبال مسیح) was a Pakistani Christian boy who became a symbol of abusive child labour in Pakistan.[1][2][3][4]

Iqbal Masih | |

|---|---|

اقبال مسیح | |

| |

| Born | 1983 |

| Died | 16 April 1995 (aged 11–12) Muridke, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Nationality | Pakistani |

| Organization | Bandhua Mukti Morcha |

| Known for | Abolitionism |

Biography

Iqbal Masih was born in 1983 in Muridke, a commercial city outside of Lahore in Punjab, Pakistan, into a poor Christian family.[1][2][3][4] At age four, he was put to work by his family to pay off their debts.[5] Iqbal's family borrowed 600 rupees (less than US$12.00) from a local employer who owned a carpet weaving business. In return, Iqbal was required to work as a carpet weaver until the debt was paid off. Every day, he would rise before dawn and make his way along dark country roads to the factory, where he and most of the other children were tightly bound with chains to the carpet looms to prevent escape. Iqbal knew his debt wouldn't be paid off anytime soon and one day couldn't take it anymore. He ripped one of the carpets and got into serious trouble with the home factory owner Hussain Khan.

Escape and activism

At the age of 10, Iqbal escaped his slavery, after learning that bonded labour was declared illegal by the Supreme Court of Pakistan.[6] He escaped and then went to the police to report Arshad, but the police brought him back to Arshad, who told the police to tie him upside down if he tried to escape again. Iqbal escaped a second time and he attended the Bonded Labour Liberation Front (BLLF) School for former child slaves and quickly completed a four-year education in only two years.[7] Iqbal helped over 3,000 Pakistani children that were in bonded labour to escape to freedom and made speeches about child labour throughout the world.

He expressed a desire to become a lawyer to better equip him to free bonded labourers, and he began to visit other countries including Sweden and the United States to share his story, encouraging others to join the fight to eradicate child slavery.[8]

In 1994 he received the Reebok Human Rights Award in Boston and in his acceptance speech he said: "I am one of those millions of children who are suffering in Pakistan through bonded labour and child labour, but I am lucky that due to the efforts of Bonded Labour Liberation Front (BLLF), I go out in freedom I am standing in front of you here today. After my freedom, I joined BLLF School and I am studying in that school now. For us slave children, Ehsan Ullah Khan and BLLF have done the same work that Abraham Lincoln did for the slaves of America. Today, you are free and I am free too."[9]

Death

"Iqbal Masih, a brave and eloquent boy who attended several international conferences to denounce the hardships of child weavers in Pakistan, was shot dead with a shotgun while he and some friends were cycling in their village of Muridke, near Lahore."[10]

Iqbal was fatally shot by the carpet Mafia, while visiting relatives in Muridke, Pakistan on 16 April 1995, Easter Sunday.[3][11] He was 12 years old at the time. His mother said she did not believe her son had been the victim of a plot by the "carpet mafia".[12] However, the Bonded Labour Liberation Front disagreed because Iqbal had received death threats from individuals connected to the Pakistani carpet industry.[12] His funeral was attended by approximately 800 mourners.

Following his death, Pakistani economic elites responded to declining carpet sales by denying the use of bonded child labour in their factories and employing the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) to brutally harass and arrest activists working for the Bonded Labour Liberation Front (BLLF). The Pakistani press conducted a smear campaign against the BLLF, arguing that child labourers receive high wages and favourable working conditions.[13]

Legacy

- Iqbal's cause inspired the creation of organizations such as Free The Children,[14] a Canada-based charity and youth movement, and the Iqbal Masih Shaheed Children Foundation,[15] which has started over 20 schools in Pakistan.

- In 1994, Iqbal visited Broad Meadows Middle School in Quincy, Massachusetts,[16] and spoke to 7th graders about his life. Inspired the famous afterschool program run by teacher Ronald Adams called ODW. When the students learned of his death, they decided to raise money with a financially productive program called "Penny Power",and build a school in his honor in Kasur, Pakistan.

- Iqbal's story was depicted in a book entitled Iqbal by Francesco D'Adamo,[17] a fictional story based on true events, from the point of view of a girl named Fatima.

- In 1994 he received the Reebok Youth in Action Award.[18]

- In 1996 the Movimiento Cultural Cristiano[19] (MCC- Christian Cultural Movement) and Camino Juvenil Solidario (CJS- Youth Solidarity Path) promoted the 16 of April as International Day against Child Slavery in Spain and South America[20]

- In 1998 the newly formed Istituto Comprensivo Iqbal Masih, a comprehensive education institute comprising several schools in Trieste, Italy, was named after him.[21]

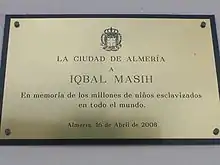

- In 2000 he received a posthumous World's Children's Prize for the Rights of the Child and the Piazzale dei Traghetti Iqbal Masih was inaugurated in Genoa, Italy.

- The 2006 book The Little Hero: One Boy's Fight for Freedom tells the story of his legacy.[22]

- In 2009 the United States Congress established the annual Iqbal Masih Award for the Elimination of Child Labor.[23]

- On 16 April 2012, the Council of Santiago, after a proposal of Movimiento Cultural Cristiano, inaugurates a Square named after Iqbal in Santiago de Compostela, Spain.[24]

- The 2014 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to children's rights advocate Kailash Satyarthi[25] on grounds of prevention of child labour and female education. Satyarthi mentioned Masih in his Nobel Peace Prize award speech, dedicating it to him and other "martyrs".[26]

- In 2016, the "X Iqbal Masih Rugby Tournament" was held in Catania, Sicily.[27]

- On 17 April 2017, the University of Salamanca committed itself to celebrate every 16 April as a Day Against Child Slavery on behalf of Iqbal Masih.[28]

References

- Fair, C. Christine; Gregory, Shaun (8 April 2016). Pakistan in National and Regional Change: State and Society in Flux. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 9781134924653.

The plight of Pakistan's bonded labourers came to international attention briefly with the murder of 12-year-old Christian Iqbal Masih in 1995.

- Winter, Jeanette (1999). Tikvah: Children's Book Creators Reflect on Human Rights. Chronicle Books. p. 84. ISBN 9781587170973.

Iqbal Masih was born into a poor Christian family in the village of Muridke, in Pakistan.

- World Vision, Volumes 38-39. World Vision. 1995. p. 41.

Police harrassment [sic] and death threats levelled at Kailash Satyarthi, chairman of the South Asian Coalition on Child Servitude, have prompted worldwide concern for the Indian activist's safety. But it's too late for Pakistani Christian Iqbal Masih, 12, a former bonded carpet-weaver who traveled the world crusading against child labor and succeeded in shutting down many carpet factories in Pakistan. On Easter Sunday, 1995, he was shot dead in his home village in Muridke. A victim of target killing.

- Ryan, Timothy (1995). "Iqbal Masih's Life -- a Call To Human Rights Vigilance". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

But on a more complex and sinister level, there is some connection between the fact that Iqbal was Christian and the fact that he was pressed into slavery in the first place.

- Iqbal Masih; Blair Underwood (2002). "Presentation and Acceptance of Reebok Youth in Action Award". In Robin Broad (ed.). Global Backlash: Citizen Initiatives for a Just World Economy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 199. ISBN 978-0742510340. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Sandy Hobbs; Jim McKechnie; Michael Lavalette (1 October 1999). Child Labor: A World History Companion. ABC-CLIO. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0874369564.

- Kile, J (20 April 2011). "Iqbal Masih".

- Chowdhry, Wilson. "Iqbal Masih Pakistan's Forgotten Hero".

- "Human Rights Youth in Action Award" (PDF).

- "Boy leader of child labour protest is shot dead". 19 April 1995.

- "Iqbal Masih's Heart-Rending Tragedy". pangaea.org. 19 January 2016.

- "Plot Discounted in Death of Pakistani Boy".

- "Child Labor in Pakistan". The Atlantic. February 1996.

- "Iqbal and Craig: Two children against child labour". 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Iqbal Masih Shaheed Children Foundation". 19 January 2016.

- "Broad Meadows Middle School, Paragraph 5". 19 January 2016.

- Francesco D'Adamo (19 January 2016). "Iqbal".

- GoodWeave (18 March 2013). "Iqbal Masih, Child Hero" – via YouTube.

- "Movimiento Cultural Cristiano – Web Oficial". www.movimientoculturalcristiano.org.

- "Welcome to the website of Iqbal Masih in solidaridad.net - Iqbal Masih". solidaridad.net.

- "Iqbal Masih - Storia". www.iqbalmasihtrieste.it. Archived from the original on 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- Crofts, Andrew (2006). The Little Hero: One Boy's Fight for Freedom - Iqbal Masih's Story.

- "Iqbal Masih Award". 19 January 2016.

- http://www.saingalicia.blogspot.com.es/2012/02/iqbal-masih-ya-tiene-plaza-en-santiago.html Plaza Iqbal Masih

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 2014". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ""Let Us March!" Nobel Lecture by Kailash Satyarthi, Oslo, 10 December 2014". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

I give the biggest credit of this honour to my movement's Kaalu Kumar, Dhoom Das and Adarsh Kishore from India and Iqbal Masih from Pakistan who made the supreme sacrifice for protecting the freedom and dignity of children. I humbly accept this award on behalf of all such martyrs, my fellow activists across the world and my countrymen.

- Stampa, Ufficio. "X Torneo "Coppa Iqbal Masih" 23/24 aprile 2016". sicilia.federugby.it.

- "Colegio Oficial de Graduados Sociales de Salamanca". www.graduadosocialsalamanca.es.

Further reading

- Andrew Crofts (15 June 2006). The Little Hero: One Boy's Fight for Freedom: Iqbal Masih's Story. Summersdale Publishers LTD - ROW. ISBN 978-1-84839-492-6.

- Susan Kuklin (15 October 1998). Iqbal Masih and the Crusaders Against Child Slavery. Henry Holt and Company (BYR). ISBN 978-0-8050-5459-0.

External links

- "Who Was Iqbal Masih?" mirrorimage.com.

- Gannon, Kathy (May 31, 1995). "Young Activist's Death Hits Pakistani Carpet Sales". Los Angeles Times.