Isabella Breviary

The Isabella Breviary (Ms. 18851) is a late 15th-century illuminated manuscript housed in the British Library, London. Queen Isabella I was given the manuscript shortly before 1497 by her ambassador Francisco de Rojas to commemorate the double marriage of her children and the children of Emperor Maximilian of Austria and Duchess Mary of Burgundy.

Origin

The work known as the breviary of Isabella I of Castile is a Breviarium Romanum made in Flanders for a Castilian nobleman Francisco de Rojas near the end of the 15th century. It was a present for Isabel at the occasion of the marriage of her children with the children of Maximilian.[n 1]

.jpg.webp)

Francisco de Rojas y Escobar was a Castilian diplomat who carried out several important diplomatic missions for Ferdinand. He negotiated the marriage between Infante Juan, the Crown Prince, and Margaret of Austria and Philip the Handsome and Infanta Joanna of Castile. The negotiations were finalized in 1495. The marriage of Joanna and Philip took place on 20 October 1496 in Lier and that of Juan and Margaret on 3 April 1497 in Burgos. On folio 436 verso of the manuscript, the arms of the Catholic Monarchs and of both the Wedding couples are painted.

Description

The manuscript is written in medieval Latin and was made according to the Dominican use.[n 2][n 3][n 4] It contains 523 folios measuring 230 x 160 mm. and the ruled space is 135 x 95 mm. The text is written in a round gothic script (gotica rotunda) in two columns of 34 lines. Columns and lines are ruled with red ink, but the ruling is barely visible.

The manuscript contains 170 miniatures and is one of the most lavishly decorated breviaries that were preserved. The miniatures are distributed as follows:

- Calendar: 12

- Proprium de tempore: 50

- Psalter: 27

- Proprium et commune Sanctorum: 81[n 5]

One can find two types of miniatures in the codex, page wide and column wide ones. There are 44 page wide miniatures and most of them are 24 lines high. One has a height of 26 lines, two of them are 19 lines high and one is only 18 lines high. In addition there are 104 column wide paintings whose height varies between nine and nineteen lines. Furthermore, the manuscript has twelve calendar pages, one full-page miniature and a folio with coats of arms and mottos on banners. It also counts eight historiated initials one of which remained unfinished.

The calendar is of the Flemish type: not all days are assigned to a saint or a typical office for a feast day, a lot of the days of the month is left open.

Starting from folio 402 the parchment is slightly different from that used before, but also the style of the handwriting, the initials and the illumination are different from the previous part of the book. And there are also differences in the lay-out, the responsories were smaller than the remainder of the text in the first part while this is no longer so from folio 402 on, with the exception of the quire that contains the folios 499-506. So scholars think that the manuscript was made in two campaigns.[m 1]

Breviaries for lay use

This breviary was not the only one in Isabella's collection; the queen owned at least twenty breviaries, according to the inventory reconstituted by Elisa Ruiz García.[a 1] We can only guess why Isabella collected so many breviaries. While it was usual in those days that the noble ladies had a book of hours for their personal devotion, a breviary was a book for the clergy. It is quite possible that, since books of hours were in the possession of the "general public", and since the upper middle class possessed luxurious versions, the highest class strove to distinguish themselves with a more "professional" prayer book, namely a breviary. Its larger format further distinguished the Isabella Breviary by accommodating a completely different illumination program.[m 2]

Many breviaries were highly decorated and were a symbol of status but often they serve very few practical purposes as they were expensive, heavy and difficult to transport without damaging them. Therefore other small versions of a breviaries were used and they were commonly called Book of hours. Upon Isabel's death they auctioned many of her breviaries and books of hours.[a 1] One of this examples published in Spanish by Philippe Pigouchet in 1498 was sold for 51 Maravedí in the auction (pp 551[a 1]) and can be download here.

The first breviaries for lay use were made for the French royal house.[n 6][n 7] Their example was soon followed by the Dukes of Burgundy of the house of Valois-Burgundy and later on by the Spanish and Portuguese royal families.

Some of the famous medieval breviaries:

- Breviary of Philippe le Bel, ca. 1290-1295, BnF Latin 1023.

- Belleville-breviarium Paris 1323-1326, BnF, Ms. Lat. 10484 view on line

- Breviary of Philip the Good, Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium, 9511 en 9026

- Breviary of Henri de Lorraine, Chazy (New York), Alice T. Miner museum

- Breviary of Eleanor of Portugal, New York, Morgan Library 2287

- Breviary of Charles V of France BnF ms. lat 1052

- Breviary of Marie de Savoie, Bibliothèque municipale de Chamberry some images on line

- Breviary van Martin of Aragon, Paris, BnF, Rothschild 2529 View on line[n 8]

- Breviary of Mattias Corvinus Rome, Vatican Library Urb. Lat. 112

- Breviary of Monte cassino, Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms 364 / 20 some images on line

- Breviary of Renaud de Bar (Winter part), Verdun, Bibliothèque municipale de Verdun, Bm 107 View on line[n 9]

- Breviary of Renaud de Bar (Summer part), London, British Library

- Grimani Breviarium, Venice, Biblioteca Marciana, Ms. Lat.X167(7531) view on line

- Breviarium Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp, Museum Mayer van den Bergh

History

It is unknown who got hold of the breviary after the death of Isabella or even during her lifetime. In his work of 1883 Waagen reports that it was taken by the French from the Escorial during the War of the Pyrenees in 1794.[a 2] but there are no documents that confirm this.

In 1815, the work is in the possession of John Dent, a British collector, banker and member of Parliament. In 1817 the manuscript was described by Thomas Frognall Dibdin.[a 3] After the dead of Dent in 1826, his collection is sold in 1827 at an auction held by Robert Harding Evans and in the catalogue four pages are devoted to the discussion of the Isabella Breviary. It was in this catalogue that a faulty interpretation of the text of Francisco Rojas lead to the story that the book was in honour of Isabella's support for the expedition of Christopher Columbus. The book is sold for £378 [a 4] to Philip Hurd, member of the Inner Temple.

Five years later, after Hurd died, the codex is once again sold on an auction at Evans and acquired by John Soane, a famous architect and the founder of the Sir John Soane's Museum; for the sum of £520 [a 5] Soane sells the breviary to John Tobin for £645.[a 6] Tobin had bought the famous Bedford Hours at the auction by Evans where Soane bought the Isabella Breviary,[m 3] and in 1833 he bought a book of hours of Joanna of Castile (add. 18852).

While the manuscript was in the possession of John Tobin, Frederic Madden the future keeper of manuscripts at the British Museum and the German art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen were given the opportunity to study the manuscript. Waagen was very impressed by the miniature of St. John at Patmos (f309r), attributed today to Gerard David.[a 7] Upon Sir John's death in 1851 the collection went to his son the Rev. John Tobin of Liscard. The reverend was approached by the bookseller William Boone who offered him £1900 for the complete collection (eight manuscripts) from his father. After the deal was closed, Boone tried to sell the manuscripts to Bertram, the 4th Earl of Ashburnham but he had no success. He then offered the collection to the British Museum for £3000 and after some hesitation due to the exorbitant price, the trustees agreed. As we have seen above, the Bedford Hours were part of the deal, so after all this may have been one of the best deals the British Museum ever made.[m 4]

Content

A breviary contains the public or canonical prayers, hymns, the Psalms, readings, and notations for everyday use, especially by bishops, priests, monks, and deacons in the Divine Office (i.e., at the canonical hours or Liturgy of the Hours. The core of the breviaries as they were in use in medieval times was the Psalter with the 150 psalms attributed to King David. In the monasteries these 150 psalms were to be recited every week and Benedict of Nursia was one of the first to set up a scheme to plan the recitation of the psalms over the week and this scheme was readily accepted. Gradually other prayers like antiphons, hymns, canticles, readings from the script, versicles and collects were added to the daily prayers and eventually a large number of different books were needed. The breviary was a collection of all the prayers that were needed to recite the daily office The first occurrence of a single manuscript of the daily office was written by the Benedictine order at Monte Cassino in Italy in 1099 but the real breakthrough came with the advent of the mendicant friars who travelled around a lot and needed a shortened, or abbreviated, daily office contained in one portable book

The Isabella Breviary contains the standard sections of a Dominican breviary as they were established by Hubert de Romans, superior of the order between 1254 and 1277 (for details see the list hereunder).

| Section | Folios | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Calendar | ff. 1v – 7r | |

| The Proprium de Tempore first part[n 10] | ff. 8v – 110v | this section starts with the first Sunday of the Advent and ends with Holy Saturday. |

| The Psalms | ff. 111v – 194r | |

| The canticles | ff. 194r – 197v | for matins, lauds, vespers and compline and for the prime on Sundays. |

| Apostles' Creed and Our father | f. 197v | |

| Litany of the Saints | ff. 198r – 200r | |

| Rubrics | ff. 203r – 208r | Explaining the class of the feast days and their mutual ranking. |

| The Proprium de Tempore second part | ff. 211r – 288v | This section covers the period from Easter up to the last Sunday before the Advent. |

| Office for the consecration of a church | ff. 288v – 292r | |

| The Proprium Sanctorum[n 11] | ff. 293r – 498r | The section starts with Andrew the Apostle (November 30) and ends with the feast of Saturnin of Rome (November 29). |

| The commune sanctorum[n 12] | ff. 498r – 508r | |

| Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary | ff. 508v – 512v | |

| Office of the Dead | ff. 512v – 514r | |

| Benedictions | ff. 514r – 514v | used by the lessons of the Matins |

| Prayers for the deceased | ff. 518v – 521r | |

| Prayers to recite before the meals | ff. 521r – 521v | and blessing of various objects |

| Various prayers | ff. 522r – 523r | Including the blessing of water (holy water) and salt. |

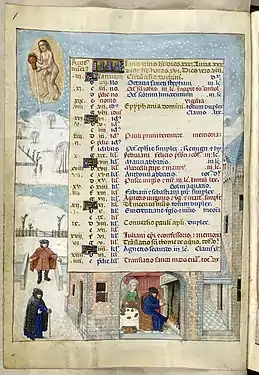

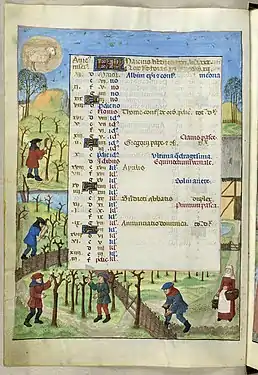

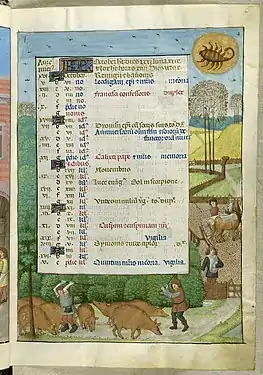

Calendar

The calendar is a calendar based on the standardised Dominican calendar drawn up by Humbert of Romans. During the third quarter of the 13th century A number of changes to the original calendar were implemented after approval by the General- Chapter of the Dominicans, but sometimes it took a long time before those changes were seen in all the monasteries.

The calendar includes several feasts of saints venerated typically by the Dominicans (see list below).

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| January 28 | Translation of Thomas Aquinas. |

| February 4 | Commemoration of the dead of members of the order. |

| March 7 | Feast of Thomas Aquinas |

| April 5 | Feast of Vincent Ferrer. |

| April 29 | Feast of Peter of Verona. |

| May 24 | Translation of Dominic. |

| July 11 | Feast of Procopius. |

| July 27 | Feast of Martha. |

| August 5 | Feast of Dominic. |

| August 25 | Feast of Saint Louis. |

| September 4 | Feast of Marcellus of Paris |

| September 28 | Feast of Wenceslas. |

| October 10 | Commemoration of the dead of members of the order. |

| December 8 | Sanctification of the Virgin Mary |

The calendar gives for every feast day the ranking: memoria, iii lectiones, simplex, semiduplex, duplex and totum duplex. This ranking is used to decide on the prayers that should be recited if the feast day of a saint coincides with a variable feast day. The used terminology is typical for the Dominicans and on the folios 203r – 208r a rubric explains how one should proceed.

Besides the feast days, the calendar contains also the computistical entries necessary to determine the day of the week corresponding to a given calendar date. In the first column one can find the golden number and in the second the Dominical letter. In the third column the date is expressed in the according to the Roman calendar with kalendae, nonae and idus. Also the date on which the sun enters a zodiacal sign is indicated in the calendar.

In the heading for each month the number of days and lunar days is given and the length of day and night is indicated.

The proprium de tempore

The proprium de tempore or temporal contains the prayers for the liturgical year, according to the calendar and starting with the Advent. The temporal specifies the prayers to be recited for the daily hours of the Divine Office: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. The prayers consist of psalms, antiphons, versicles, responses, hymns, readings from the Old and New Testaments, sermons of the Fathers and the like. The recurring prayers like the hymns, psalms and canticles are normally not repeated in the breviary but are identified by a reference to the section of the book where the prayer in question can be found, but in the Isabella Breviary the hymns were integrated in the temporal and the Sanctoral, the manuscript has no separate hymnarium. The references to the psalms etc. are written in read ink and are called rubrics.

When one tries to read the temporal or the sanctoral it will be noted that the office for Sundays and major holidays start with the Vespers of the previous day. This was standard practice, the celebration of a feast began with the vigil the night before.

The Isabella Breviary is also quite exceptional by the fact that the temporal is divided in two parts by the Psalter. This could mean that the original source from which the breviary was copied, may have consisted of two parts, a winter and a summer breviary and that during the writing of the text of the Isabella Breviary, someone decided to create it as a single volume. A winter and a summer breviary normally contain each the entire Psalter between the temporal and the sanctoral. The Isabella Breviary was probably made in two campaigns. The first campaign stopped when the winter part of the temporal and the Psalter were completed but before the winter part of the sanctoral was written. In the second phase the scribe continued with the summer part of the temporal, followed by a complete sanctoral and the remaining sections.

The Psalter

The Psalter in the Isabella Breviary consists of the 150 psalms of the Book of Psalms the first book of the "Writings", the third section of the Hebrew bible.[a 8] In the Jewish and Western Christian tradition there are 150 psalms. The order in which they should be recited during the week depends on the liturgical use. The Isabella Breviary followed the Dominican use that is summarized in the table here under. The psalms are numbered here according to the medieval vulgate, later versions and translations like the KJV use a different numbering.

| Hour | Weekday | Psalms |

|---|---|---|

| Matins | ||

| Sunday | 1-3, 6-20 | |

| Monday | 26-37 | |

| Tuesday | 38-41, 43-49, 51 | |

| Wednesday | 52, 54-61, 63, 65, 67 | |

| Thursday | 68-79 | |

| Friday | 80-88, 93, 95-96 | |

| Saturday | 97-108 | |

| Lauds [n 13] | ||

| Sunday | 92, 99, 62, 66, Benedicite, 148-150 | |

| Monday | 50, 5, 62,66, Confitebor, 148-150 | |

| Tuesday | 50, 42, 62,66, Ego dixi, 148-150 | |

| Wednesday | 50, 64, 62,66, Exultavit, 148-150 | |

| Thursday | 50, 89, 62,66, Cantemus, 148-150 | |

| Friday | 50, 142, 62,66, Domine audivi, 148-150 | |

| Saturday | 50, 91, 62,66, Audite, 148-150 | |

| Prime | all | 53, 118:1-32 |

| Terce | all | 118:33-80 |

| Sext | all | 118:81-128 |

| None | all | 118:129-176 |

| Vespers | ||

| Sunday | 109-113 | |

| Monday | 114-116, 119-120 | |

| Tuesday | 121-125 | |

| Wednesday | 126-130 | |

| Thursday | 131, 132, 134-136 | |

| Friday | 137-141 | |

| Saturday | 143-147 | |

| Compline | all | 4, 30:1-5, 90, 133 |

In the Psalter of the breviary, the psalms are in numerical order starting with psalm 1 "Beatus vir" up to psalm 150 "Laudate dominum", such a Psalter is called a "Psalterium non feriatum", but in the Isabella Breviary some psalms are copied a second time and grouped with another psalm to make it easier for the user. An example hereof is psalm 53 ("Deus in nomine tue") that figures on f139v in de numerical order but is repeated on f176r prior to psalm 118 because they are recited in that order during prime on every weekday. Another example is psalm 94 that can be found on f111v at the very beginning of the Psalter and also on f161v in numerical order.

The proprium Sanctorum

The proprium Sanctorum or Sanctoral is functionally equivalent to the Temporal. It contains the offices to be used on the saints’ days. Normally there should be a one-to-one correspondence between the calendar and the Sanctoral, but like in most breviaries there are some minor differences.

The decoration

One of the purposes of the decoration of a manuscript like Isabella's Breviary was to make it easier to use the book by structuring the text. A strict hierarchy can be recognized in the decoration. The largest miniatures are used to mark the most important sections or feasts, the smaller ones indicate subsections or less important Sundays or feasts. Initials and border decoration are used to complement miniatures or to mark divisions of the text like. individual psalms and psalm verses.

In the winter part of the Temporal de page-wide miniatures are used for the main Sundays and for the feast days in the week. Lesser Sundays are illustrated with a column-wide miniature and weekdays with a partial border and a large ornamental initial. The Matins of Maundy Thursday are illustrated with 16 column-wide miniatures illustrating the passion of Christ

In the Psalter the page-wide miniatures were used to illustrate the opening psalm in the Matins for Sunday and the weekdays (1, 26, 38, 52, 68, 80 and 97) but also the Vespers on Sunday and the Gradual Psalms are marked with a page-wide miniature. The opening psalms for the Vespers of the other days and for the lesser hours are illustrated with a small miniature.

The page-wide miniatures are used in the summer part for the important feasts (Easter, Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday and three other Sundays.

In the Sanctoral the page-wide miniatures are reserved for the great saints and the typical Dominican saints. A number of saints’ offices are illustrated with a column-wide miniature and some with a historiated initial. The use of historiated initials is limited to the first folia of the Sanctoral. Probably the initial plan was to use historiated initials and then later on it was decided to use small miniatures instead.[m 5]

Page-wide miniatures

The manuscript contains a number of miniatures that are page wide and 24 lines high except a couple of them in the Sanctoral. These miniatures are always accompanied by a complete border decoration (4 sides) and a large decorated initial of eight lines. In the table hereunder the feasts illustrated with a page wide miniature are listed.

List of page-wide miniatures

| Folium | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal (winter part) | ||

| f8v | The twelve Sibyls (full-page miniature) | Beginning of the winter part of the temporal |

| f9r | David on his deathbed | First Sunday of Advent |

| f29r | The adoration of the shepherds | Christmas |

| f37r | Circumcision of Christ (Luke 2:21) | First of January |

| f41r | The Adoration of the Magi (Matthew 2:1-12) | Epiphany |

| f63r | God creating the animals | Septuagesima, the first Sunday of the Easter cycle |

| f71r | The Temptation of Christ (Matthew 4:1-11) | The first Sunday of Lent (Quadragesima Sunday) |

| f77r | Christ and the Canaanite Woman (Matthew 15:21-28) | The second Sunday of lent |

| f81v | Evicting of a dumb devil (Luke 11:14-28) (Lucas 11:14-28) | The third Sunday of Lent |

| f86r | Jesus and the woman taken in adultery (John 8:1-11) | The fourth Sunday of Lent |

| f90r | Jews threaten to stone Christ (John 8:46-59) | Passion Sunday |

| f96r | The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (Matthew 21:1-9) | Palm Sunday |

| f100r | The Washing of the Feet and the Last Supper (John 30:25-6) | Maundy Thursday |

| f106v | The Crucifixion | Good Friday |

| Psalter (Introduced by a diptych of page-wide miniatures) | ||

| f111v | Nebukadnezar burning the books of the Temple | Beginning of the Psalter, Psalm 94 Venite exultemus; matins invitatory |

| f112r | The rebuilding of Jerusalem | Beginning of the Psalter, Psalm 1 Beatus vir; Sunday Matins |

| f124r | David is anointed as King | Psalm 26 Dominus illuminatio mea; Monday Matins |

| f132r | David is cursed and stoned by Shimei | Psalm 38 Dixi custodiam; Tuesday Matins |

| f139r | Antiochus plundering the Temple of Jerusalem | Psalm 52 Dixit insipiens; Wednesday Matins |

| f146v | David and the Temple singers | Psalm 68 Saluum me fac Deus; Thursday Matins |

| f155v | David with musicians for the Tabernacle | Psalm 80 Exultate Deo: Friday Matins |

| f164r | David with musicians learning a new song | Psalm 97 Cantate domino canticum novum; Saturday Matins |

| f173r | Abraham rescues Lot from his enemies | Psalm 109 Dixit Dominus Domino; Sunday Vespers |

| f184v | David and his musicians climb the stairs of the temple | Psalm 119 Ad Dominum cum tribularer; First gradual psalm |

| Temporal (summer part) | ||

| f211r | The Risen Christ | Temporal (summer part), Holy Saturday |

| f228r | The Ascension of Jezus | Feast of the Ascension |

| f234v | The descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and the Virgin | Pentecost |

| f241r | Mercy Seat and St. Augustine with a child on the beach | Trinity Sunday |

| f252r | Parable of Dives and Lazarus (Lucas 16:19-31) | First Sunday after Trinity Sunday |

| f260r | Salomon instructing Rehoboam (Proverbs 1:1-10) | First Sunday in August |

| f262r | The trials of Job (Job 1:18-19) | First Sunday in September |

| Sanctoral | ||

| f293r | Martyrdom of St. Andrew | First Saint in the Sanctoral |

| f297r | SaintBarbara | |

| f309r | John on Patmos | |

| f337r | Purification of the Virgin Mary or presentation of Jesus at the Temple | |

| f348r | Thomas Aquinas and the speaking crucifix | |

| f354r | Annunciation | |

| f365r | Peter Martyr | |

| f368r | Saint Catherine of Siena | |

| f386v | Nativity of John the Baptist | |

| f392r | The martyrdom of Peter [n 14] and Paul | |

| f399r | The Visitation (the visit of Mary to her cousin Elizabeth) | |

| f436v | Full-page miniature with the arms of Ferdinand en Isabella | |

| f437r | Coronation of the Virgin Mary (18 lines) and weapons of Francisco de Rojas | |

| f455r | Emperor Heraclius carries the cross of Christ into Jerusalem (21 lines) | |

| f477v | All Saints in heaven (19 lines) | |

| f481r | Resurrection of Lazarus (Feast of All Souls)) (19 lines) |

Temporal

Within the major sections the text is divided by column-wide miniatures. The second, third and fourth Sunday of the advent for example are marked with a miniature of 13 or 14 lines high and a four-sided border decoration.

The important feast days in the Christmastide are Christmas, the Circumcision of Jesus and the Adoration of the Magi, which are illustrated by a page-wide miniature. The Sundays after the octave of the Epiphany and the beginning of the Easter cycle are indicated by an initial of eight lines high and a three-sided margin decoration. The first Sunday of the Easter cycle is marked with a page-wide miniature, but the Sundays before the start of Lent and Ash Wednesday have small miniatures. From the first Sunday of lent up to Easter, all Sundays and feast-days are indicated with a large miniature. After Easter up to the beginning of the Advent, all Sundays have a small miniature except the important feasts and the first Sunday of August and September.

Elsewhere, small miniatures are used to illustrate the text, as is the case with the Passion of Christ on the folia 101r to 104r.

| Folium | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Winter part | ||

| f14v | The day of Judgment (Luke 21:23-55) | Second Sunday of Advent |

| f18r | John the Baptist sent two of his disciples to Christ (Matthew 11:2-10) | Third Sunday of Advent |

| f23r | John explains his message out to the Pharisees (John I :19-28) | Fourth Sunday of Advent |

| f65v | Noah's Ark (Genesis 6) | Sexagesima, second Sunday before Ash Wednesday |

| f67v | Abraham goes to the promised land (Genesis 12) | Quinquagesima, Sunday before Ash Wednesday |

| f69v | A priest placing crosses of ashes on the foreheads of adherents’ | Ash Wednesday |

| f100v | Christ praying in Gethsemane (Matthew 26:40) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f100v | Christ addressing the soldiers (John 18:5-6) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f101r | The kiss of Judas (Matthew 26:51) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f101r | Christ before Annas (John 18:13-23) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f101v | Christ before Caiaphas (Matthew 26:57-66) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f101v | The mocking of Christ (Matthew 26:67-68)[n 15] | Illustration of the Passion |

| f102r | Christ before Pontius Pilate (Luke 23:1-6) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f102r | Christ is brought to Herod Antipas (Luke 23:7) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f102v | Christ before Herod | Illustration of the Passion |

| f102v | Christ brought back to Pilate | Illustration of the Passion |

| f103r | Christus a second time before Pilate (Luke 23:13-24) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f103r | Christ being scourged (Mark 15:15) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f103v | Crown of thorns (Matthew 27:27-31) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f103v | Ecce Homo (John 19:5) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f104r | Christ Carrying the Cross (John 19:23-24) | Illustration of the Passion |

| f104r | Christ waiting for his crucifixion, and the dividing of his seamless robe | Illustration of the Passion |

| f108v | Soldiers sleeping around the tomb of Christ | Holy Saturday |

| Rubrics[n 16] | ||

| f203r | A Dominican reading for a group of monks. | Rubrics explaining the use of the breviary. |

| Summer part | ||

| f220v | John on Patmos | Readings from the Apocalypse |

| f263v | Tobias distributing bread (Tobias :19-20) | Matins readings in the second week of September |

| f266r | Alexander the Great defeats Darius (I Maccabees 1:1-2) | Matins readings for October |

| f270r | Prophets in a church praying to God | Matins readings for November |

| Dedication of a church [n 17] | ||

| f298r | Dedication of a church | Office for the dedication of a church |

Psalter

Also in the Psalter there are numerous psalms illustrated with a small miniature based on the text of the psalm or the psalm commentaries from Nicholas of Lyra[a 9] In the Psalter the small miniatures are used to point to the beginning of psalms for Vespers of the week and the beginning of the small tidal psalms (prime, tierce, sext and none). The initial Psalms of Lauds and Compline are not represented by a miniature.

| Folium | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| f174r | Passage of the Red Sea (Exodus 14:23-37) | Psalm 113 In exitu israel de egypto; Final Psalm of Sunday Vespers |

| f174v | David takes the cup and the spear out of the tent of Saul (I Samuel 26:12-13) | Psalm 114 Dilexi quoniam exaudiet; Monday Vespers |

| f176r | A man from Ziph betray the whereabouts of David to Saul (1 Samuel 22:14-20) | Psalm 53 Deus in nomine tuo; Prime |

| f177v | Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden (Genesis 4:23-24) and a Terceentecostal scene | Psalm 118:33-80 Legem pone michi domine;: |

| f180r | Jacob's Ladder (Genesis 28:12-14) | Psalm 118:81-128 Defecit in salutare tuam; Sext |

| f182r | A woman praying in a rose garden | Psalm 118:129-176 Mirabilia testimonia tua; None |

| f185r | Solomon oversees the construction of the temple | Psalm 121 Letatus sum; Tuesday Vespers |

| f186r | Christ and the saints in heaven above a church | Psalm 126 Nisi dominus aedificaverit; Wednesday Vespers |

| f187r | The Ark is placed in the temple (II Kings 6:15) | Psalm 131 Memento domine; Thursday Vespers |

| f189r | Goliath challenges the Israelites to single combat (1 Samuel 17:4-10) | Psalm 137 Cofitebor tibi; Friday Vespers |

| f191v | The fight between David en Goliath (I Samuel 17:40-51)) | Psalm 143 Benedictus dominus; Saturday Vespers |

Canticles and Litany

The text of the canticles, prayers or hymns from the Bible, of the Old Testament and the New Testament is illustrated with a few small miniatures

| Folium | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Canticles | ||

| f194r | Baptism of St Augustine | Te Deum |

| f194v | The three children in the fiery furnace (Daniel 3:52-90) | Benedicite, omnia opera |

| f195v | Visitation (Luke 1:46-55) | Magnificat (Canticle of Mary) |

| f196r | Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (Luke 2:29-32) | Nunc dimittis (Canticle of Simeon) |

| f196v | The Pope looks on in burning heretical books | Quicumque vult (Athanasian Creed) |

| Litany | ||

| f198r | Leaders of church and state pray to Christ | Litany |

The Common of Saints

The beginning of the Common of Saints on f499r is announced by a column-wide miniature of 12 lines high representing the twelve apostles. This page has also a four sided margin decoration. It is the last, fully decorated page in the manuscript.

The sections of the Common are marked with a decorated initial of four lines high but without miniatures or historiated initials.

Sanctoral

The largest number of illustrations can be found in the Proprium Sanctorum or Sanctoral, 81 of the 178 feasts are illustrated with a miniature. The Sanctoral contains almost half of the 170 miniatures illuminating the manuscript. The choice of ventilation depends on the 'use' of the breviary. In a breviary for use Dominican people will make different selections than in a breviary for Cistercian use. The choice of the saints to represent, aside from the major saints that are found in any breviary, depends of course on the “use” of the breviary but also on the preferences of the customer or the person for whom the book was intended. Considering that this manuscript was made for Dominican use, the Dominican saints like Dominic, Thomas Aquinas, Peter of Verona, Vincent Ferrer, Catherine of Siena and Procopius take an important place.

Also here, small pictures were used as a kind of bookmarks but also to illustrate the symbols of the saint with possibly a representation of his martyrdom, or a special event in his life. In the list below, one can see a full list of the miniatures, with a brief description. The page-wide miniatures are included in the list. The dates of the holidays in this list may differ from the dates that can be found in the modern Calendar of saints because the Dominican calendar sometimes differs from the Roman calendar some feast-days have changed since the Middle Ages.

| Folio | Date | H[n 18] | Typ[n 19] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| f293r | 30/11 | 24 | PW | Andrew, apostle and his death on the cross. In the background a story about Andrew from the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine is depicted. |

| f297r | 4/12 | 24 | PW | Saint Barbara seated in a closed garden next to her icon, the tower. In the landscape in the background her life and martyrdom are depicted. |

| f297v | 6/12 | 9 | I | Saint Nicholas, the initial was never historiated and remained empty. |

| f301r | 8/12 | 12 | CW | Coronation of the Virgin by the Trinity |

| f303r | 13/12 | 7 | I | Lucia van Syracuse with a book and a column[n 20] |

| f304v | 21/12 | 9 | I | Thomas the Apostle, With a spear as attribute.[n 21] |

| f306r | 26/12 | 9 | I | Saint Stephen, the first martyr, with book and stones (he was stoned to death). |

| f309r | 27/12 | 24 | PW | John the Evangelist on Patmos. He is pictured with his symbol, the eagle, writing on a scroll. In the landscape in the background one can see three of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse . |

| f312r | 28/12 | 12 | CW | The Innocent Children, with a picture of the Infanticide of Bethlehem. |

| f314v | 29/12 | 12 | CW | Thomas Becket; Thomas stands at the altar with his chaplain, while behind him his murderers approach. |

| f320v | 17/1 | 9 | I | Anthony of Egypt, abbot and hermit, in a black robe with a staff and a book bag. |

| f322v | 20/1 | 9 | I | Fabian en Saint Sebastian. Fabian as a bishop with his staff and Sebastian fixed to a pillar and pierced with arrows. Besides their common feast date, there is no relation between these saints. |

| f324r | 21/1 | 10 | I | Agnes, standing in a landscape with a lamb, her attribute based on her name (agnus = lamb). The palm branch she holds is the symbol of her martyrdom. |

| f326r | 22/1 | 12 | I | Vincent of Saragossa with palm branch and book in his hands. |

| f328v | 25/1 | 13 | CW | Conversion of Paul the Apostle. Paul falls with his horse and in the air, we see his vision of Christ. |

| f331v | 28/1 | 15 | CW | De Translation of Thomas Aquinas. Thomas is depicted in a garden holding a chalice while his staff and mitre lay on the ground. He is crowned by an angel. Staff and mitre are erroneous attributes, Thomas was not a bishop. |

| f337v | 2/2 | 24 | PW | Purification of the Virgin or the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, also called Candlemas. |

| f345v | 22/2 | 14 | CW | Chair of Saint Peter. Christ speaks to Peter kneeling with Tiara, with in the background the chair of Peter. |

| f347r | 24/2 | 14 | CW | Matthew the Apostle. Matthew is depicted in a landscape with a book and a try square. He is usually depicted with a spear or halberd, believed to be the tool of his martyrdom, but here the artist preferred to the square, his symbol as Patron Saint of the carpenters.. |

| f348r | 8/3 | 24 | PW | Thomas Aquinas and the miracle of the speaking Crucifix. |

| f354r | 25/3 | 24 | PW | Annunciation. The miniature shows the annunciation with the traditional iconography but with a Tree of Jesse in the background. This combination is quite rare but can be explained by the text of Isaiah (11:1): “And there shall come forth a rod out of the root of Jesse”, that is added to the lessons for Matins in the Dominican breviary. |

| f358r | 5/4 | 14 | CW | Vincent Ferrer, a Dominican looking up to a vision of Christ in the sky.. |

| f363r[n 22] | 23/4 | 12 | CW | Saint George fighting the dragon. The princess he was rescuing is kneeling in the background. |

| f364r[n 22] | 25/4 | 10 | CW | Mark the Evangelist writing in a room in the company of a lion, his symbol. |

| f365r[n 23] | 29/4 | 24 | PW | Peter of Verona The miniature shows a Dominican kneeling, with a dagger in his side and writing “Credo” with his blood on the ground. |

| f367r[n 22] | 1/5 | 12 | CW | Philip and James the Less, apostles. They are depicted in a landscape. Philip is holding a cross-staff while James holds a fuller’s club, the tool of his martyrdom. |

| f368r[n 22] | 2/5 | 24 | PW | Catherine of Siena, was a tertiary of the Dominican Order. She is depicted with a crucifix and flowers in her right hand and a heart in her left. Catherine is crowned with a crown of thorns. |

| f372r[n 23] | 3/5 | 12 | CW | The Invention of the Cross by Saint Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. The scene shows Helena looking at a man digging with a pick-axe. |

| f374r[n 23] | 4/5 | 13 | CW | Feast of the crown of thorns. The miniature shows a seated Christ being crowned with thorns. |

| f385v[n 22] | 22/6 | 12 | CW | Saint Acacius and the Ten thousand martyrs. The miniature depicts a number of corpses on thorn bushes at the foot of a hill. |

| f386v[n 23] | 24/6 | 24 | PW | Nativity of John the Baptist. The miniature shows the room where John was born. The midwife and her assistant are preparing a bath for the baby and Zacharias, in the left foreground, is writing the name of the newborn in a book (Luke, 1:57-64). |

| f390r[n 23] | 26/6 | 12 | CW | John and Paul, martyrs. John and Paul were beheaded in Rome under Julian the Apostate (361-3). It is clear that the artist had no example of iconography to use, for he depicts John as John the Baptist holding a lamb and the apostle Paul holding a sword. |

| f392r[n 23] | 29/6 | 24 | PW | Peter and Paul, apostles. The miniature shows the two apostles being beheaded, what is correct for Paul but Peter was crucified according to the tradition. |

| f399r[n 23] | 2/7 | 24 | PW | Visitation. This miniature was painted around 1500, probably by a Spanish artist. The building on the right is in a classical style, not used by the Flemish painters. |

| f404v | 10/7 | 14 | CW | The Seven Brothers, the seven sons of Felicitas of Rome. |

| f405r | 11/7 | 13 | CW | Saint Procopius. He is depicted as an abbot holding a book and his crosier. His mitre is placed on the altar to the right. Procopius founded the abbey of Sázava in Bohemia. He is one of the Saints added to the calendar and the sanctoral by the Dominicans to “internationalise” the list of saints. This is also the case with Louis IX, Wenceslaus of Bohemia and Edward the Confessor.[m 6] |

| f405v | 17/7 | 12 | CW | Alexius of Rome, depicted holding an open book and a sceptre and a ladder beside him. |

| f406v | 20/7 | 9 | CW | Margaret of Antioch. Margaret steps out of the dragon with a crucifix in her hands. |

| f407v | 21/7 | 14 | CW | Praxedes holding a palm and a book. Roman martyr, second century. |

| f408r | 22/7 | 12 | CW | Mary Magdalene depicted in a landscape with mount Calvary and holding an ointment jar, her attribute. |

| f411r | 23/7 | 13 | CW | Apollinaris of Ravenna as bishop, reading a book and holding crosier and sword. |

| f412v | 25/7 | 15 | CW | James the Great, reading a book and holding a pilgrim’ staff. A scallop shell is fixed on his hat. |

| f414r | 26/7 | 14 | CW | Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, a very popular depiction in Flanders. |

| f417r | 27/7 | 15 | CW | Martha reading a book and holding keys and a ladle, illustrating her attention with domestic affairs.. |

| f418r | 29/7 | 15 | CW | Felix, Simplicius, Faustinus and Beatrix Roman martyrs. Nearly nothing is known about the Roman martyr Felix who was confused with Antipope Felix II. In the miniature he is presented as a pope. Either Simplicius or Faustinus is represented as a bishop. This is also an error for both of then were laymen. Beatrix was the sister of Simplicius and Faustinus and died also as a martyr. There is no relation between Felix and the others except for the fact that their feast days are on the same day, July 29. |

| f419v | 1/8 | 14 | CW | The Liberation of Saint Peter from jail by an angel, according to the Acts 12. |

| f421v | 3/8 | 14 | CW | Inventio[n 24] van Saint Stephen. He is represented as a deacon in a dalmatic with two stones on his head. In the left hand he holds a book ant with the right hand he holds up his dalmatic filled with stones. Stephen was the first martyr and was stoned to death. |

| f423v | 5/8 | 14 | CW | Saint Dominic, The founder of the Dominican Order. He is depicted in a landscape with a dog holding a flaming brand to his left and a daemon head at his right. It is astonishing that he got only a small miniature in a breviary for Dominican use. |

| f427r | 6/8 | 14 | CW | The Transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor (Matthew 17:4-5) |

| f431r | 10/8 | 14 | CW | Lawrence of Rome. The miniature shows Lawrence as a deacon holding a book and a gridiron. He was martyred by burning on a gridiron. |

| f437r | 15/8 | 18 | PW | Assumption of Mary. The miniature shows the crowning of the Virgin Mary by the Trinity. Around the throne are music-playing angels. This theme is not the normal theme used for the illustration of the assumption. In contemporary Flemish breviaries this feast is illustrated by either de dead of the Virgin or by the Virgin carried up to heaven by angels. In the border under the miniature, the Arms of Francesco de Rojas were painted. On the opposite page there is a full page miniature with the arms of Ferdinand and Isabella and those of the two couples that were going to be married. |

| f441r | 20/8 | 15 | CW | Bernard of Clairvaux with book and crosier and dressed in a Cistercian habit. Beside Bernard are a dog and a chained devil. |

| f442v | 24/8 | 16 | CW | Bartholomew. Depicted in a landscape, holding a knife and a book bag. His attribute the knife, was the tool of his martyrdom, he was flayed alive. |

| f444r | 25/8 | 14 | CW | Saint Louis, king of France. |

| f445v | 28/8 | 13 | CW | Augustine seated as a bishop, with a heart in his right hand and a crosier in the other. |

| f449r | 29/8 | 16 | CW | Beheading of St. John the Baptist situated in a landscape. John points to the Lamb of God sitting on a book and holding a crucifix. Normally one should find a miniature of Salome receiving the head of John, it seems that the miniaturist choose the wrong theme. |

| f451v | 8/9 | 19 | CW | The birth of Mary. One can see a midwife presenting the baby to Anne and Joachim, who is kneeling in the foreground. |

| f455r | 9&11/9 | 17 | PW | Gorgonius, Protus and Hyacinth. The page-wide miniature is divided in two by a column. The left half depicts Gorgonius standing before a wall with a sword in his hands, behind the wall we see Protus and Hyacinth holding a book. In the other half, the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross is illustrated. Emperor Heraclius is depicted, bare footed, porting the cross through the gate of Jerusalem. |

| f458r | 16/9 | 15 | CW | Euphemia with a sword and a millstone. Euphemia was the daughter of a Roman senator and was martyred under the reign of Diocletian. |

| f459r | 21/9 | 16 | CW | Matthew the Apostle the evangelist with his symbol, the angle, writing at a desk in his study. |

| f461r | 22/9 | 13 | CW | Saint Maurice and his companions. Maurice is depicted in armour, holding a sword and reading a book. Four of his companions are standing at his side. |

| f462r | 27/9 | 12 | CW | Cosmas and Damian were twin brothers and physicians according to Christian tradition. They are depicted, one with a urine bottle in his hand, the other with a mortar and pestle. |

| f463v | 28/9 | 15 | CW | Saint Wenceslaus, duke of Bohemia depicted with sword and book before a landscape. |

| f464r | 29/9 | 15 | CW | Archangel Michael in armour with a sword, fighting a dragon and trampling a demon. |

| f476v | 30/9 | 12 | CW | Jerome dressed as a cardinal sitting in a landscape with a lion. |

| f468v | 1/10 | 16 | CW | Remigius of Reims depicted as Saint Bavo. He is depicted as a knight on a horse holding sword and shield. |

| f469v | 4/10 | 15 | CW | Francis of Assisi receiving the stigmata. |

| f470v | 7/10 | 14 | CW | Pope Mark with tiara and crosier, reading a book. |

| f471r | 9/10 | 15 | CW | Denis and his companions Eleuterus and Rusticus. He stands in a landscape with a chapel in the background and is head is half decapitated. In the iconography of St Denis he is often represented walking and carrying his own head after he was decapitated. |

| f472v | 13/10 | 13 | CW | Translation of Edward the Confessor with sceptre and an open book in front of a cloth of honour. |

| f473r | 18/10 | 13 | CW | Luke the Evangelist in his study working on a painting of the Holy Virgin. Is symbol, the bull or the oxen is also depicted. |

| f474v | 21/10 | 16 | CW | Saint Ursula and the eleven thousand virgins. They are depicted in a landscape with Ursula flanked by two of her companions in front of a procession of virgins. Ursula is holding arrows in her hands. |

| f467r | 28/10 | 16 | CW | Simon the Zealot or Simon the apostle and Jude the Apostle. Simon, patron of the carpenters is holding a saw and Jude is reading a book. |

| f477v | 1/11 | 19 | PW | All Saints' Day. The miniature shows the Trinity, Father and Son enthroned and the Holy Ghost in the form of a dove hovering above them. Below the throne we see Mary flanked by two female saints and surrounded by a large crowd of saints, both clergy and laity. |

| f481r | 2/11 | 19 | PW | All Souls' Day. The raising of Lazarus is depicted on the miniature. This is a quite unusual theme for All Souls' Day in Flemish art. |

| f484v | 8/11 | 14 | CW | Four Crowned Martyrs. The martyrs represented on the miniature are Claudius, Nicostratus, Simpronianus and Castoris, four stonemasons who were martyred in Rome in the early fourth century. They are holding the tools of their trade like trowel, hammer, chisels, a set square and a large wooden plank. One of them is holding a book. |

| f485r | 9/11 | 16 | CW | Theodore of Amasea, also known as Theodore Tiro. He is represented as a richly dressed lay person, but in fact he was a soldier and should have been depicted as such. |

| f485v | 11/11 | 15 | CW | Martin of Tours, dividing his cloak to share it with a naked cripple at the gate of the city. |

| f488v | 19/11 | 16 | CW | Elizabeth of Hungary. She is depicted standing before a cloth of honour carrying two crowns. One as a symbol of her worldly status and the other to symbolize her sanctity. |

| f491v | 22/11 | 17 | CW | Saint Cecilia, depicted in a niche. She is reading a book while holding a portative organ in her arm. Cecilia is the patron of musicians. |

| f494r | 23/11 | 17 | CW | Pope Clement I. The miniature depicts Clement in a landscape with a ship on the sea in the background. He wears a tiara and holds a processional cross, a big anchor is lying behind him. He was martyred by throwing him in the sea with an anchor tied to his neck. |

| f495v | 25/11 | 17 | CW | Catherine of Alexandria. She is depicted standing in a landscape holding a sword and a book. In the background one can see the broken wheel. She is trampling emperor Maxentius, her crowned persecutor, who holds a sceptre in his hand. This iconography was popular in Flanders.[a 10] |

The calendar miniatures

The calendar miniatures are not a part of the hierarchical system described above, they are not intended to structure or clarify the text, but are purely decorative. The calendar miniatures are the only real full-page miniatures in the manuscript. They seem to have been set up as a kind of full-page miniature of a landscape in which the works of the month were displayed. Over the (virtual) central part of that landscape, the calendar text is written. The zodiac sign of the month is always placed in the upper left or right corner.

The use of real full-page miniatures for the calendar started in France in the third quarter of the fifteenth century. In the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Limbourg Brothers used full-page miniatures of the works of the month facing the calendar page. Their invention was scarcely followed by other artists until it was picked up by Flemish painters in the beginning of the sixteenth century as for example in the Grimani Breviary. The Isabella Breviary was one of the earliest manuscripts in which the technique of "overwritten" full-page miniatures for the calendar was applied.[m 7]

Initials

This manuscript contains literally thousands of decorated initials. They are between one and eight lines high. All the characters are drawn with blue or purple ink on a gold background, and parts of the initials are decorated with geometric motifs in white. The open space within the initial is usually decorated with vines or floral motifs, sometimes with geometric structures. For the larger initials the corners are often cut. The initials are, like the miniatures, also used to structure the text. For example, in the Psalter each psalm starts with an initial of 3 lines high.[n 25]

Line fillers

If the line is ending with a blank space, this is filled with a gold bar which buds, tendrils or geometric motifs. In the Psalter this line fillers are widespread, they are used to mark the end of the verses. Sometimes, instead of the gold bar, a kind of chain of o's written in red ink is used.

Borders

Margin decoration is also extensively used in the manuscript. Each page with a large or small miniature has a full, four-sided border decoration. The decoration is also applied in the space between the two text columns.

It Isabella Breviary one can find the already outmoded French border decoration alongside scatter borders invented in Flanders around 1470.

French border decoration originated in Paris in the early 15th century in the vicinity of the Boucicaut Master and the Bedford Master. This type was adopted in Flanders and further developed. To emphasize the distinction with the then ultramodern Ghent-Bruges style it is called "outmoded" French here. The Ghent-Bruges style of border decoration was first used around 1470 in the vicinity of the Master of Mary of Burgundy, Lieven van Lathem, and the master of Margaret of York.

The outmoded border decorations were painted on the blank parchment. There are two variants of this. The first (type-a) has delicate acanthus scrolls painted in blue and gold, with strawberries, small flowers, leaves and twigs and small gold dots. The other version (type-b) has the same features but with only blue, gold, and black (see example).

In the "modern" Ghent-Bruges style, the border decoration is painted on a painted background, usually painted in yellow. The proper decoration is then painted on the coloured border. Also for this type of border we can distinguish different types.

In the first variant the artist uses broad acanthus branches in white or gold, sometimes knotted or interwoven. Between the acanthus there are thin-stemmed flowers, some strawberries, insects and birds. Here and there we see human figures or between branches climbing the branches (see example).

The second variant consists of much thinner acanthus tendrils sprouting flowers (see example). .

The third variant are the so-called the scatter borders, where flowers and flower buds are scattered over the painted border (see example).

Sometimes the outmoded French borders are combined with a narrow scatter border that is surrounding the text ore miniature. The scatter borders and the outmoded French borders are the most commonly used types throughout the manuscript..

Here and there the border decoration is completely different. Some borders have the appearance of fabric, or consist of text written in large capital letters. A good example of such a fabric margin can be seen on the miniature with Saint Barbara at the top of the article.

Examples of the different types of border decoration.

Outmoded French border type a, f67v

Outmoded French border type a, f67v Outmoded French border type b, f69v

Outmoded French border type b, f69v Ghent-Bruges style variant 1, f112r

Ghent-Bruges style variant 1, f112r Ghent-Bruges style variant 2, f374r

Ghent-Bruges style variant 2, f374r Ghent-Bruges style variant 3, f184v

Ghent-Bruges style variant 3, f184v Sample of a combined border, f101r

Sample of a combined border, f101r Sample of the special types

Sample of the special types

In addition to the four-side full page borders, or framing three sides of it, one van find also partial borders ranging from a couple of lines high to full-page height. These small borders are used together with decorated initials to structure the text. This type of decoration can be found on literally every page of the manuscript and in that context, one can say that all the 1048 pages of the book are decorated (with the exception of a couple completely blank pages.

Full-page border decoration is generally used on a page with a miniature, be it small or large, but here and there one can find full-page border decoration in combination with large initials as introduction of a new section in the manuscript where no miniature was planned. Examples of this situation can be found on folios 13r, 13v and 14r with the prayers for the days of the first week of Advent.

The artists

Master of the Dresden Prayer Book

The largest number of miniatures was painted by the artist known as the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book. There are one full-page miniature, 32 page-wide en 52 column-wide miniatures attributed to this master.[m 8] This master eschewed the use of models[a 11] and his inventivity in the illumination of the Isabella Breviary is remarkable. The iconography used in his illustrations of the Psalter was completely new in Flanders. Admittedly, the miniatures were based on newly published theological works,[a 9][a 12] but it seems unlikely that the miniaturist had read these works himself. He was probably advised by a theologian and it would not be surprising if it would have been a Dominican.

Dating the contributions of the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book remains a difficult issue. Until recently, his work in the manuscript was dated according to the inscription on folio 437r around the time of the double marriage and the presence of Francisco de Rojas in Flanders, thus in the 1490s. But recent research, [a 13] dates the work on stylistic grounds, earlier in the previous decade, so in the 1480s, and before 1488 when the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book left Bruges for several years, returning after 1492 when the political situation in Bruges was stable again..

Calendar Master

The illustration of the calendar was probably realised in the same period as the work of the Dresden master, but although the latter was specialised in calendar illumination,[m 9] this part of the work is not from his hand. The illuminator who painted the calendar was also involved in the realisation of the border decoration in the Ghent-Bruges style variant 1, with the broad acanthus branches. The characters he painted here and there in the borders are very similar to those in the calendar. The calendar is artistically the weakest part of the illumination of the breviary.

Gerard David

When Gustav Friedrich Waagen studied the book for the first time in 1838, he already noted that four of the miniatures were of an exceptional quality: the miniature with the nativity scene at f29r, the Adoration of the Magi on f41r, St. Barbara on f297r and John on Patmos on f309r. Waagen knew very well the Adoration of the Magi kept in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich and attributed to Gerard David but he did not attribute the very similar miniature in the Isabella Breviary to David, but in his opinion, the four miniatures were of the same hand. Recent research attributes these miniatures to Gerard David[a 14] but the discussion between scholars about this attribution is ongoing.[m 10] The similarity in composition between the miniature and the painting is striking, but the miniature can of course be painted by another miniaturist who based his composition on the work of David. In any case it is recognised more en more that Gerard David played an important role in the late miniature art in Flanders.[a 15] The difference between these four miniatures and the rest of the miniatures in the first campaign by the master of Dresden is obvious. The velvety surface, the rich colour palette and the refined modelling of these miniatures sets them apart from the other in the first part. Detailed study learns that the foreground and background of the St. Barbara (f297r) have been painted with different techniques[a 16] and that is also the case for the left part of the landscape on the miniature of John (f09r).

Master of James IV of Scotland

Also this illuminator is only known to us through a nickname, some scholars identify him as Gerard Horenbout [a 17] while others don't agree at all.[a 18][a 19] The painter's name is derived from a portrait of James IV of Scotland which, together with one of his Queen, is in the Prayer book of James IV and Queen Margaret, a book of hours commissioned by James and now in Vienna in the Austrian National Library as Cod. 1897. Het was one of the great illuminators in the period between 1480 and 1530 and apart from the Isabella Breviary, he was involved in the illumination of the Breviarium Mayer van den Bergh and of the Breviarium Grimani.

The Master of James IV of Scotland was responsible for 48 miniatures in the second part of the Isabella Breviary,[n 26] the second half of the Sanctoral. In this part of the manuscript all the miniatures are column-wide except those on ff. 437r, 477v and 481r (The raising of Lazarus) . These miniatures are less high then the large ones in the first part of the breviary. Through comparison with his other work, his contribution is dated in the 1490s.[m 11] A typical difference between the miniatures realised by the Dresden master and those painted by the James master is that the latter are always framed with a three-dimensional golden frame.

Later updates

We saw that the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book finished his work on folio 358 recto and the Master of James IV of Scotland started on folio 404 verso. The miniatures in the intermediate quires must therefore be attributed to other illuminators.

English artist, early 19th century

We know from the description of the manuscript by Dibdin[a 3] that in his time the miniature of Saint Catharina was lacking. In light here of, and based on the modern style and painting technique reminiscent of oil painting, this miniature and four small column-wide miniatures (f363r, f364r, f367r and f385v) must be assigned to an early 19th-century English artist.[a 20]

Spanish artist ca. 1500

The other miniatures that were not performed, nor in the campaign of the master of Dresden, or in the second campaign with the Master of James IV of Scotland, are assigned to one hand. Based on style and on the clothing of the figures, the classical temple on f399r it is thought that this must have been an artist of Spanish origin.[m 12] It remains an open question whether this Spanish artist made these miniatures after the second campaign in 1500, or that he was appointed to finish the book after the first campaign around 1488. In the second case, he must have been removed from that job because of a significantly lower quality of his work.[m 13]

Sources, references and notes

Sources

- Janet Backhouse, The Isabella Breviary, London, The British Library, 1993

- Scot McKendrick, Elisa Riuz Garcia, Nigel Morgan, The Isabella Breviary, The British Library, London Add. Ms. 18851, Barcelona, Moleiro, 2012

References to The Isabella Breviary

- The Isabella Breviary, p. 95.

- The Isabella Breviary, p. 50.

- The Isabella Breviary, p. 61.

- The Isabella Breviary, pp. 62-63.

- The Isabella Breviary, pp. 98-99

- The Isabella Breviary, p.246

- The Isabella breviary, p. 125

- The Isabella Breviary p.99 note 17

- The Isabella Breviary p.102

- The Isabella Breviary p.103

- The Isabella Breviary, p. 106.

- The Isabella Breviary, pp.106-109.

- The Isabella Breviary, p. 109.

General references

- Elisa Ruiz García, Los Libros de Isabel la Católica: Arqueologia de un patrimonio escrito, 2004, Salamanque; inventory on pp. 371-582.

- Gustav Friedrich Waagen, Works of Art and Artists in England, 3 vols. London, 1838, p. 177.

- Thomas Frognall Dibdin, The Bibliographical Decameron, 3vols. London, 1817, Vol I, pp. 163-168.

- Evans, London, March 29th, 1827, lot 484; the lot number is written in pencil on the first flyleaf.

- Evans, London, 29 March 1832, lot 1434.

- Edward Morris, Early Nineteenth-Century Liverpool Collectors of Late Medieval Manuscripts, in Costambeys, Hammer et Heale, The Making of the Middle Ages. Liverpool Essays, Liverpool, 2007, p. 162.

- G.F. Waagen, Works of art ant artists in England, 3 vols, 1838, p.177.

- Mazor, Lea (2011). "Book of Psalms". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine. The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. p. 589.

- Nicolas de Lyre, Pastilla super Psalmos, 1486.

- Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting, 2 vols, New York 14971, pp.96-7.

- Bodo Brinkman, Die Flämische Buchmalerei am Ende des Burgunderreichs: Der Meister des Dresdener Gebetbuchs und die Miniaturisten seiner Zeit, Turnhout 1996, Brepols. pp.207-208.

- Philippus de Barberis, Sybillarum et prophetarum de Christo vaticinia, 1479

- Bodo Brinkman, 1996, pp.139-142.

- Hans J. Van Miegroet, Gerard David, Antwerp 1989, Mercatorfonds, pp.327-328.

- T. Kren & S. McKendrick (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance - The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, pp. 344-365

- Diane G. Scillia, Gerard David's St. Elisabeth of Hungary in the Hours of Isabella the Catholic, Cleveland, Studies in the History of Art, 7(2002), p.57).

- Thomas Kren, Scot McKendrick, 2003, p. 431.

- Brigitte Dekeyzer, Herfsttij van de Vlaamse miniatuurkunst - Het breviarium Mayer van den Bergh, Ludion, Gent-Amsterdam, 2004, p. 204.

- Biography of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Janet Backhouse, The Isabella Breviary, London, British Library, p.44.

Notes

- On Folio 437 recto the Coat of arms and the motto of Francisco de Rojas can be found together with the dedication of the codex.

- Until the council of Trent every bishop had full power to regulate the Breviary of his own diocese; and this was acted upon almost everywhere. Each monastic community, also, had one of its own.

- The House of Trastámara, the line to which Isabella and Ferdinand belonged, had very narrow connections with the Dominican order. Vincent Ferrer was one of the judges of the court that decided on the succession in Aragon, in favour of the Trastámara’s, with the Compromise of Caspe in 1412.

- The calendar of saints in the Isabella breviary matches perfectly with the Dominican calendars in Missals printed between 1485 and 1500 like the Breviarium Fratrem Predicatorem printed by Anton Koberger in Nuremberg in 1485 (Cambridge University Library, Inc. 6. a. 7.2, ISTC: ib01141300)

- In the office of Nicholas of Myra space for the miniature is foreseen, but the miniature was not painted.

- The first one was made for Philip IV of France ca. 1290-1295, BnF Latin 1023.

- Another well known example is the Belleville Breviary 1323-1326 made for Jeanne de Belleville and illustrated by Jean Pucelle, BnF Latin 10484.

- Via Mandragore; click Recherche, type "Rothschild 2529" in the field Cote and hit enter or click Chercher; next click Images

- Doesn’t work with all web browsers.

- Contains the prayers for a given feast or saint festival.

- The Proprium Sanctorum or Sanctoral contains the prayers to be used on the feast day of a Saint.

- This comprises psalms, antiphons, lessons, &c., for feasts of various groups or classes (twelve in all); e.g. apostles, martyrs, confessors, virgins, and the Blessed Virgin Mary. These offices are of very ancient date, and many of them were probably in origin proper to individual saints.

- The text gives the de incipit of the canticle.

- Peter was crucified, not beheaded. The painter made a small error.

- In the margin the denial by Peter (Mark 14:66-68)

- This text is in fact not a part of the Temporale but is inserted before the beginning of the summer part.

- The dedication of a church has nothing to do with the Temporal.

- Height in number of lines

- PW : page-wide; CW: column-wide; I: historiated initial

- The column is not the normal attribute for Lucia, she is usually depicted with a dagger through her throat and with a lamp as an allusion to her name (lux = light) or a pair of eyes on a scale.

- According to the “Acts of Thomas” he was killed in India with spears.

- Added in the 19th century

- Added ca. 1500

- Inventio: the discovery of the relics or the tomb of a saint.

- This is true for the psalms with a sequence number greater than 4, starting on folio 115 verso, with two exceptions. The exceptions are probably an error of the scribe who forgot to leave sufficient space for the initial.

- From f402r up to f524 with exception of the quire ff. 499-506.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isabella Breviary (c.1497) - BL Add MS 18851. |

- London, British Library, Add. MS 18851: complete digitization

- Moleiro facsimile with references to miniatures