Bartholomew the Apostle

Bartholomew (Aramaic: ܒܪ ܬܘܠܡܝ; Ancient Greek: Βαρθολομαῖος, romanized: Bartholomaîos; Latin: Bartholomaeus; Armenian: Բարթողիմէոս; Coptic: ⲃⲁⲣⲑⲟⲗⲟⲙⲉⲟⲥ; Hebrew: בר-תולמי, romanized: bar-Tôlmay; Arabic: بَرثُولَماوُس, romanized: Barthulmāwus) was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. He has also been identified as Nathanael or Nathaniel,[2] who appears in the Gospel of John when introduced to Jesus by Philip (who also became an apostle; John 1:43–51), although many modern commentators reject the identification of Nathanael with Bartholomew.[3]

Bartholomew the Apostle | |

|---|---|

Saint John and Saint Bartholomew (right) by Dosso Dossi, 1527 | |

| Apostle and martyr | |

| Born | 1st century AD Cana, Galilee, Roman Empire |

| Died | 1st century AD Albanopolis, Armenia[1] |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints |

| Major shrine | Saint Bartholomew Monastery in historical Armenia, Relics at Basilica of San Bartolomeo in Benevento, Italy, Saint Bartholomew-on-the-Tiber Church, Rome, Canterbury Cathedral, the Cathedrals in Frankfurt and Plzeň, and San Bartolomeo Cathedral in Lipari |

| Feast | August 24 (Western Christianity) June 11 (Eastern Christianity) |

| Attributes | Knife and his flayed skin, Red Martyrdom |

| Patronage | Armenia; bookbinders; butchers; Florentine cheese and salt merchants; Gambatesa, Italy; Catbalogan, Samar; Magalang, Pampanga; Malabon, Metro Manila; Nagcarlan, Laguna; San Leonardo, Nueva Ecija, Philippines; Għargħur, Malta; leather workers; neurological diseases; skin diseases; dermatology; plasterers; shoemakers; curriers; tanners; trappers; twitching; whiteners; Los Cerricos (Spain); Barva, Costa Rica |

According to the Synaxarium of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Bartholomew's martyrdom is commemorated on the first day of the Coptic calendar (i.e., the first day of the month of Thout), which currently falls on September 11 (corresponding to August 29 in the Julian calendar). Eastern Christianity honours him on June 11 and the Catholic Church honours him on August 24. The Church of England and other Anglican churches also honour him on August 24.[4]

The Armenian Apostolic Church honours Saint Bartholomew along with Saint Thaddeus as its patron saints. Bartholomew is English for Bar Talmai (Greek: Βαρθολομαῖος, transliterated Bartholomaios in Greek) comes from the Aramaic: בר-תולמי bar-Tolmay native to Hebrew "son of Talmai", or farmer, "son of the furrows".[5] Bartholomew is listed among the Twelve Apostles of Jesus in the three synoptic gospels: Matthew,[10:1–4] Mark,[3:13–19] and Luke,[6:12–16] and also appears as one of the witnesses of the Ascension;[Acts 1:4, 12, 13] on each occasion, however, he is named in the company of Philip. He is not mentioned by the name "Bartholomew" in the Gospel of John, nor are there any early acta,[lower-alpha 1] the earliest being written by a pseudepigraphical writer, Pseudo-Abdias, who assumed the identity of Abdias of Babylon and to whom is attributed the Saint-Thierry (Reims, Bibl. mun., ms 142) and Pseudo-Abdias manuscripts.[6][7]

In art Bartholomew is most commonly depicted with a beard and curly hair at the time of his martyrdom. According to legends he was skinned alive and beheaded so is often depicted holding his flayed skin or the curved flensing knife with which he was skinned.[8]

New Testament references

In the East, where Bartholomew's evangelical labours were expended, he was identified as "Nathanael", in works by Abdisho bar Berika (often known as "Ebedjesu" in the West), the 14th century Nestorian metropolitan of Soba, and Elias, the bishop of Damascus.[lower-alpha 2] Nathanael is mentioned only in the Gospel of John. In the Synoptic Gospels, Philip and Bartholomew are always mentioned together, while Nathanael is never mentioned. In John's gospel, however, Philip and Nathanael are similarly mentioned together. Giuseppe Simone Assemani specifically remarks, "the Chaldeans confound Bartholomew with Nathaniel".[lower-alpha 3] Some Biblical scholars reject this identification, however.[9][lower-alpha 4]

Tradition

Eusebius of Caesarea's Ecclesiastical History (5:10) states that after the Ascension, Bartholomew went on a missionary tour to India, where he left behind a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. Other traditions record him as serving as a missionary in Ethiopia, Mesopotamia, Parthia, and Lycaonia.[10] Popular traditions and legends say that Bartholomew preached the Gospel in India, then went to Greater Armenia.[5]

Mission to India

Two ancient testimonies exist about the mission of Saint Bartholomew in India. These are of Eusebius of Caesarea (early 4th century) and of Saint Jerome (late 4th century). Both of these refer to this tradition while speaking of the reported visit of Pantaenus to India in the 2nd century.[11] The studies of Fr A.C. Perumalil SJ and Moraes hold that the Bombay region on the Konkan coast, a region which may have been known as the ancient city Kalyan, was the field of Saint Bartholomew's missionary activities.Previously the consensus among scholars was against the apostolate of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in India. Majority of the scholars are skeptical about the mission of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in India . Stililingus (1703), Neande (1853), Hunter (1886), Rae (1892), Zaleski (1915) are the authors who supported the Apostolate of Saint Bartholomew in India. Scholars such as Sollerius (1669), Carpentier (1822), Harnack (1903), Medlycott (1905), Mingana (1926), Thurston (1933), Attwater (1935) etc does not support this hypothesis.The main argument is that the India, Eusebius and Jerome refers here should be Ethiopia or Arabia Felix.[11]

In Armenia

Along with his fellow apostle Jude "Thaddeus", Bartholomew is reputed to have brought Christianity to Armenia in the 1st century. Thus, both saints are considered the patron saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

One tradition has it that Apostle Bartholomew was executed in Albanopolis in Armenia. According to popular hagiography, the apostle was flayed alive and beheaded. According to other accounts he was crucified upside down (head downward) like St. Peter. He is said to have been martyred for having converted Polymius, the king of Armenia, to Christianity. Enraged by the monarch's conversion, and fearing a Roman backlash, King Polymius's brother, Prince Astyages, ordered Bartholomew's torture and execution, which Bartholomew endured. However, there are no records of any Armenian king of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia with the name "Polymius". Current scholarship indicates that Bartholomew is more likely to have died in Kalyan in India, where there was an official named "Polymius".[12][13]

The 13th-century Saint Bartholomew Monastery was a prominent Armenian monastery constructed at the site of the martyrdom of Apostle Bartholomew in Vaspurakan, Greater Armenia (now in southeastern Turkey).[14]

Relics

The 6th-century writer in Constantinople, Theodorus Lector, averred that in about 507, the Byzantine emperor Anastasius I Dicorus gave the body of Bartholomew to the city of Daras, in Mesopotamia, which he had recently refounded.[15] The existence of relics at Lipari, a small island off the coast of Sicily, in the part of Italy controlled from Constantinople, was explained by Gregory of Tours[16] by his body having miraculously washed up there: a large piece of his skin and many bones that were kept in the Cathedral of St Bartholomew the Apostle, Lipari, were translated to Benevento in 838, where they are still kept now in the Basilica San Bartolomeo. A portion of the relics was given in 983 by Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor, to Rome, where it is conserved at San Bartolomeo all'Isola, which was founded on the temple of Asclepius, an important Roman medical centre. This association with medicine in course of time caused Bartholomew's name to become associated with medicine and hospitals.[17] Some of Bartholomew's alleged skull was transferred to the Frankfurt Cathedral, while an arm was venerated in Canterbury Cathedral.

Miracles

Of the many miracles claimed to have been performed by Bartholomew before and after his death, two of which are known by the townsfolk of the small Italian island of Lipari.

The people of Lipari celebrated his feast day annually. The tradition of the people was to take the solid silver and gold statue from inside the Cathedral of St Bartholomew and carry it through the town. On one occasion, when taking the statue down the hill towards the town, it suddenly became very heavy and had to be set down. When the men carrying the statue regained their strength, they lifted it a second time. After another few seconds, it got even heavier. They set it down and attempted once more to pick it up. They managed to lift it but had to put it down one last time. Within seconds, walls further downhill collapsed. If the statue had been able to be lifted, all the townspeople would have been killed.[4]

During World War II, the fascist regime looked for ways to finance their activities. The order was given to take the silver statue of Saint Bartholomew and melt it down. The statue was weighed, and it was found to be only a few grams. It was returned to its place in the Cathedral of Lipari. In reality, the statue is made from many kilograms of silver and it is considered a miracle that it was not melted down.[18]

Saint Bartholomew is credited with many other miracles having to do with the weight of objects.

Art and literature

The appearance of the saint is described in detail in the Golden Legend: "His hair is black and crisped, his skin fair, his eyes wide, his nose even and straight, his beard thick and with few grey hairs; he is of medium stature..."[19] Christian tradition has three stories about Bartholomew's death: "One speaks of his being kidnapped, beaten unconscious, and cast into the sea to drown. Another account states that he was crucified upside down, and another says that he was skinned alive and beheaded in Albac or Albanopolis", near Başkale, Turkey.[20]

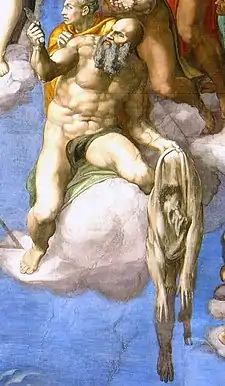

St Bartholomew is the most prominent flayed Christian martyr.[21] During the 16th century, images of the flaying of Bartholomew were so popular that it came to signify the saint in works of art.[22] Consequently, Saint Bartholomew is most often represented being skinned alive.[23] Symbols associated with the saint include knives (alluding to the knife used to skin the saint alive) and his skin, which Bartholomew holds or drapes around his body.[22] Similarly, the ancient herald of Bartholomew is known by "flaying knives with silver blades and gold handles, on a red field."[24] As in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, the saint is often depicted with both the knife and his skin.[23] Representations of Bartholomew with a chained demon are common in Spanish painting.[22]

Saint Bartholomew is often depicted in lavish medieval manuscripts.[25] Manuscripts, which are literally made from flayed and manipulated skin, hold a strong visual and cognitive association with the saint during the medieval period and can also be seen as depicting book production.[25] Florentine artist Pacino di Bonaguida, depicts his martyrdom in a complex and striking composition in his Laudario of Sant’Agnese, a book of Italian Hymns produced for the Compagnia di Sant’Agnese c. 1340.[21] In the five scene, narrative based image three torturers flay Bartholomew's legs and arms as he is immobilised and chained to a gate. On the right, the saint wears his own flesh tied around his neck while he kneels in prayer before a rock, his severed head fallen to the ground. Another example includes the Flaying of St. Bartholomew in the Luttrell Psalter c.1325–1340. Bartholomew is depicted on a surgical table, surrounded by tormentors while he is flayed with golden knives.[26]

Due to the nature of his martyrdom, Bartholomew is the patron saint of tanners, plasterers, tailors, leatherworkers, bookbinders, farmers, housepainters, butchers, and glove makers.[22] In works of art the saint has been depicted being skinned by tanners, as in Guido da Siena's reliquary shutters with the Martyrdoms of St. Francis, St. Claire, St. Bartholomew, and St. Catherine of Alexandria.[27] Popular in Florence and other areas in Tuscany, the saint also came to be associated with salt, oil, and cheese merchants.[28]

Although Bartholomew's death is commonly depicted in artworks of a religious nature, his story has also been used to represent anatomical depictions of the human body devoid of flesh. An example of this can be seen in Marco d'Agrate's St Bartholomew Flayed (1562) where Bartholomew is depicted wrapped in his own skin with every muscle, vein and tendon clearly visible, acting as a clear description of the muscles and structure of the human body.[29]

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1634) by Jusepe de Ribera depicts Bartholomew's final moments before being flayed alive. The viewer is meant to empathize with Bartholomew, whose body seemingly bursts through the surface of the canvas, and whose outstretched arms embrace a mystical light that illuminates his flesh. His piercing eyes, open mouth, and petitioning left hand bespeak an intense communion with the divine; yet this same hand draws our attention to the instruments of his torture, symbolically positioned in the shape of a cross. Transfixed by Bartholomew's active faith, the executioner seems to have stopped short in his actions, and his furrowed brow and partially illuminated face suggest a moment of doubt, with the possibility of conversion.[30] The representation of Bartholomew's demise in the National Gallery painting differs significantly from all other depictions by Ribera. By limiting the number of participants to the main protagonists of the story—the saint, his executioner, one of the priests who condemned him, and one of the soldiers who captured him—and presenting them halflength and filling the picture space, the artist rejected an active, movemented composition for one of intense psychological drama. The cusping along all four edges shows that the painting has not been cut down: Ribera intended the composition to be just such a tight, restricted presentation, with the figures cut off and pressed together.[31]

The idea of using the story of Bartholomew being skinned alive to create an artwork depicting an anatomical study of a human is still common amongst contemporary artists with Gunther Von Hagens's The Skin Man (2002) and Damien Hirst's Exquisite Pain (2006). Within Gunther Von Hagens's body of work called Body Worlds a figure reminiscent of Bartholomew holds up his skin. This figure is depicted in actual human tissues (made possible by Hagens's plastination process) to educate the public about the inner workings of the human body and to show the effects of healthy and unhealthy lifestyles.[32] In Exquisite Pain 2006, Damien Hirst depicts St Bartholomew with a high level of anatomical detail with his flayed skin draped over his right arm, a scalpel in one hand and a pair of scissors in the other. The inclusion of scissors was inspired by Tim Burton's film Edward Scissorhands (1990).[33]

Bartholomew plays a part in Francis Bacon's Utopian tale New Atlantis, about a mythical isolated land, Bensalem, populated by a people dedicated to reason and natural philosophy. Some twenty years after the ascension of Christ the people of Bensalem found an ark floating off their shore. The ark contained a letter as well as the books of the Old and New Testaments. The letter was from Bartholomew the Apostle and declared that an angel told him to set the ark and its contents afloat. Thus the scientists of Bensalem received the revelation of the Word of God.[34]

Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin in Michelangelo's The Last Judgment.

Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin in Michelangelo's The Last Judgment. St Bartholomew Flayed, by Marco d'Agrate, 1562 (Duomo di Milano)

St Bartholomew Flayed, by Marco d'Agrate, 1562 (Duomo di Milano) Statue of Bartholomew at the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran by Pierre Le Gros the Younger.

Statue of Bartholomew at the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran by Pierre Le Gros the Younger. Shield showing three flaying knives, symbol of St. Bartholomew, at the Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania)

Shield showing three flaying knives, symbol of St. Bartholomew, at the Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania) Saint Bartholomew Simone Martini, circa 1317-1319

Saint Bartholomew Simone Martini, circa 1317-1319

Culture

The festival in August has been a traditional occasion for markets and fairs, such as the Bartholomew Fair which was held in Smithfield, London, from the Middle Ages,[35] and which served as the scene for Ben Jonson's 1614 homonymous comedy.

St Bartholomew's Street Fair is held in Crewkerne, Somerset, annually at the start of September.[36] The fair dates back to Saxon times and the major traders' market was recorded in the Domesday Book. St Bartholomew's Street Fair, Crewkerne is reputed to have been granted its charter in the time of Henry III (1207–1272). The earliest surviving court record was made in 1280, which can be found in the British Library.

In Islam

The Qur’anic account of the disciples of Jesus does not include their names, numbers, or any detailed accounts of their lives. Muslim exegesis, however, more-or-less agrees with the New Testament list and says that the disciples included Peter, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew, Matthew, Andrew, James, Jude, John and Simon the Zealot.[37]

See also

- St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

- St Bartholomew's Hospital

- Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, patron saint archive

- Bertil

- Bartholomeus

References

Notes

- Smith & Cheetham 1875 noted the "absence of any great amount of early trustworthy tradition."

- Both noted, Ebedjesu as "Ebedjesu Sobiensis", in Smith & Cheetham 1875, who give their source, Giuseppe Simone Assemani Bibliotheca Orientalis iii.i. pp. 30ff.

- Bartholomaeum cum Nathaniel confundunt Chaldaei Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, iii, pt 2, p. 5 (noted by Smith & Cheetham 1875).

- for the identification see Benedict XVI 2006

Citations

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Green, McKnight & Marshall 1992, p. 180.

- Smith 1999, p. 75.

- Damo-Santiago 2014.

- Butler & Burns 1998, p. 232.

- Fabricius 1703, p. 341.

- Lillich 2011, p. 46.

- Bissell 2016.

- Meier 1991, pp. 199–200.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Micropædia. vol. 1, p. 924. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998. ISBN 0-85229-633-9.

- "Mission of Saint Bartholomew, the Apostle in India". Nasranis. October 10, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Fenlon 1907.

- Spilman 2017.

- "The Condition of the Armenian Historical Monuments in Turkey". raa.am. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Smith & Cheetham 1875, p. 179.

- Gregory, De Gloria Martyrum, i.33.

- Attwater & John 1995.

- "Saint Bartholomew the Apostle". timelineindex.com. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- de Voragine & Duffy 2012, pp. xxi, 496.

- Teunis 2003, p. 306.

- Mittman & Sciacca 2017, pp. viii, 141.

- Giorgi 2003, p. 51.

- Crane 2014, p. 5.

- Post 2018, p. 12.

- Kay 2006, pp. 35–74.

- Mittman & Sciacca 2017, pp. 42.

- Decker & Kirkland-Ives 2017, p. ii.

- West 1996.

- "The statue of St Bartholomew in the Milan Duomo". Duomo di Milano. June 29, 2018. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- "The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew". nga.gov. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- DeGrazia & Garberson 1996, p. 410.

- "Philosophy". Body Worlds. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Dorkin 2003.

- Bacon 1942.

- Cavendish 2005.

- "About the Fair". Crewkerne Charter Fair, Somerset – (Formerly St.Bartholomew's Street Fair). Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Noegel & Wheeler 2002, p. 86: Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon

Sources

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1995). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051312-7.

- Bacon, Francis (1942). New Atlantis. New York: W. J. Black.

- Benedict XVI (October 4, 2006). "General Audience". vatican.va. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Bissell, Tom (March 1, 2016). "A Most Violent Martyrdom". Lapham’s Quarterly. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Butler, Alban; Burns, Paul (1998). Butler's Lives of the Saints: August. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-86012-257-9.

- Cavendish, Richard (September 9, 2005). "London's Last Bartholomew Fair". History Today. Vol. 55 no. 9.

- Crane, Thomas Frederick (2014). Tales from Italy: When Christianity Met Italy. M&J. ISBN 979-11-951749-4-2.

- Damo-Santiago, Corazon (August 28, 2014). "Saint Bartholomew the Apostle skinned alive for spreading his faith". BusinessMirror. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Decker, John R.; Kirkland-Ives, Mitzi (2017). "Death, Torture and the Broken Body in European Art, 1300 - 1650 ". Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-57009-1.

- DeGrazia, Diane; Garberson, Eric (1996). Italian Paintings of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Edgar Peters Bowron, Peter Lukehart, Mitchell Merling. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-241-4.

- de Voragine, Jacobus; Duffy, Eamon (2012). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-4205-0.

- Dorkin, Molly (2003), "Sotheby's", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t079852

- Fabricius, Johann Albert (1703). Codex Apocryphus Novi Testamenti: collectus, castigatus testimoniisque, censuris & animadversionibus illustratus. sumptib. B. Schiller.

- Fenlon, John Francis (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Giorgi, Rosa (2003). Saints in Art. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-717-7. OCLC 50982363.

- Green, Joel B.; McKnight, Scot; Marshall, I. Howard (1992). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1777-1.

- Kay, S. (2006). "Original Skin: Flaying, Reading, and Thinking in the Legend of Saint Bartholomew and Other Works". Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 36 (1): 35–74. doi:10.1215/10829636-36-1-35. ISSN 1082-9636.

- Lillich, Meredith Parsons (2011). The Gothic Stained Glass of Reims Cathedral. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-03777-6.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: Companions and competitors. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-46993-7.

- Mittman, Asa Simon; Sciacca, Christine (2017). Tracy, Larissa (ed.). Flaying in the Pre-modern World: Practice and Representation. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-452-5.

- Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. ISBN 978-0-8108-4305-9.

- Post, W. Ellwood (2018). Saints, Signs, and Symbols. Papamoa Press. ISBN 978-1-78720-972-5.

- Smith, Dwight Moody (1999). Abingdon New Testament Commentaries. Vol.4: John. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-05812-9.

- Smith, William; Cheetham, Samuel (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities: A-Juv. J. Murray.

- Spilman, Frances (2017). The Twelve: Lives and Legends of The Apostles. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-365-64043-8.

- Teunis, D. A. (2003). Satan's Secret: Exposing the Master of Deception and the Father of Lies. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4107-3580-5.

- West, Shearer (1996). The Bloomsbury Guide to Art. Bloomsbury. OCLC 246967494.

Further reading

- Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Hardcastle, Kate (2016). A Dictionary of First Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880051-4.

- Perumalil, A. C. (1971). The Apostles in India. Jaipur: Xavier Teachers' Training Institute.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bartholomew the Apostle. |

| Old Testament |

|---|

|

- The Martyrdom of the Holy and Glorious Apostle Bartholomew, attributed to Pseudo-Abdias, one of the minor Church Fathers

- St. Bartholomew's Connections in India

- St. Bartholomew at the Christian Iconography web site.'

- "The Life of St. Bartholomew the Apostle" in the Caxton translation of the Golden Legend