Ithell Colquhoun

Ithell Colquhoun (9 October 1906 – 11 April 1988) was a British painter, occultist, poet and author. Stylistically her artwork was affiliated with surrealism. In the late 1930s, Colquhoun was part of the British Surrealist Group before being expelled because she refused to renounce her association with occult groups.

Ithell Colquhoun | |

|---|---|

Head 1931 (Self Portrait) | |

| Born | Margaret Ithell Colquhoun 9 October 1906 Shillong, Eastern Bengal and Assam, British India |

| Died | 11 April 1988 (aged 81) Cornwall, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Slade School of Fine Art |

| Known for | Surrealist painter and author |

Colquhoun was born in Shillong, Eastern Bengal and Assam, British India, but brought up in the United Kingdom. After studying at the Slade School of Art, she lived briefly in Paris before moving back to London. She spent the latter part of her life in Cornwall, where she died in 1988.

Biography

Margaret Ithell Colquhoun was born in Shillong, Eastern Bengal and Assam, British India,[1] the daughter of Henry Archibald Colebrooke Colquhoun and Georgia Frances Ithell Manley. Colquhoun was educated in Rodwell, near Weymouth, Dorset before attending Cheltenham Ladies' College.[2] She became interested in occultism aged 17, after reading Aleister Crowley's Abbey of Thelema.[3] Colquhoun gained admission to the Slade School of Art in London in October 1927, and was taught by Henry Tonks and Randolph Schwabe. While at the Slade, she joined G.R.S. Mead's Quest Society, and in 1930 published her first article, "The Prose of Alchemy", in the society's journal.[3] In 1929, Colquhoun received the Slade's Summer Composition Prize for her painting Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes, and in 1931 it was exhibited in the Royal Academy.[4] Despite her studies at the Slade, Colquhoun was primarily a self-taught artist.[2]

In 1931, after leaving the Slade, Colquhoun moved to Paris, where she established a studio.[4] She was introduced to surrealism there, in 1931 reading Peter Neagoe's essay What is Surrealism?,[5] and her interest in the movement was deepened in 1936 when she saw Salvador Dalí lecture at the International Exhibition of Surrealism in London.[6]

Colquhoun's first solo exhibition was at the Cheltenham Art Gallery in 1936;[2] a solo exhibition at the Fine Art Society in London followed in the same year.[4] In 1937 she joined the Artists' International Association,[2] and in the late 1930s she became increasingly associated with the surrealist movement in Britain, writing three articles for the London Bulletin in 1938 and 1939,[7] visiting André Breton in Paris in 1939,[6] and joining the British Surrealist Group in the same year.[2] Also in 1939, she exhibited with Roland Penrose at the Mayor Gallery,[4] showing 14 oil paintings and two objects.[7]

After only a year as a member of the British Surrealist Group, Colquhoun was expelled in 1940, due to her refusal to comply with E.L.T. Mesens' demands that the surrealists should not be members of any other groups, which Colquhoun felt would interfere with her studies of occultism. This led to Colquhoun's exclusion from other exhibitions organised by the British surrealists, but she continued to work with surrealist principles.[6]

In 1946, Colquhoun bought a studio near Penzance in Cornwall, and divided her time between there and London; in 1957 she moved to Paul, Cornwall.[2]

Colquhoun died in 1988. She left her occult work to the Tate, and her other art to the National Trust. In 2019, the Tate acquired the National Trust's holdings of Colquhoun's works.[8]

Art

Though only formally involved with the surrealist movement in England for a few years, Colquhoun first gained her reputation as a surrealist, and identified as a surrealist for the rest of her life.[9] She used many automatic techniques,[2] which were described in André Breton's first surrealist manifesto as a defining feature of surrealism,[10] and invented several automatic techniques herself.[2]

Colquhoun had an early interest in biology, and studies of plants and flowers were a recurring theme in her art throughout her life. Many of her early notebooks contained very detailed drawings of plants,[11] and her early works included a series of enlarged images of flora, occupying the full canvas and painted almost photographically.[2]

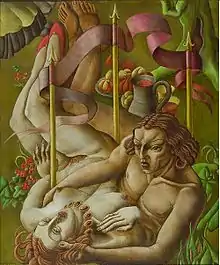

Colquhoun's work also often explored themes of sex and gender.[12] Her early work often depicts powerful women from myth and Bible stories, such as Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes 1929, and Susanna and the Elders 1930 – both of which are likely homages to Artemisia Gentileschi's works on the same themes.[13] Dawn Ades sees Colquhoun's treatment of gender as responding to the masculine and patriarchal themes in the art of other surrealists – for instance, where other surrealists drew landscapes as women, Colquhoun's Gouffres Amers 1939 shows a male body as a landscape.[7]

Stylistically, some her works have been described as "macabre" and sinister."[14] In 1939, she created the work Tepid Waters (Rivières Tièdes) which was displayed at her solo exhibition at the Mayor Gallery the same year. The work was political in content, referring to the Spanish Civil War.

In the 1940s, Colquhoun began to create works exploring the themes of consciousness and the subconscious. Her interest in psychology and dreams also attached her to the Surrealism movement.

She used a wide range of materials and methods, such as decalcomania, fumage, frottage and collage. Colquhoun went further, developing new techniques such as superautomatism, stillomanay, parsemage, and entoptic graphomania writing about them in her article The mantic stain.[2]

Three works which stand out during the 1940s are The Pine Family, which deals with dismemberment and castration, A Visitation which shows a flat heart shape with multicoloured beams of light and Dreaming Leaps, a homage to Sonia Araquistain.[2]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Colquhoun turned her attention towards collages rather than painting. The last retrospective of her work was held at the Newlyn Orion Gallery in 1976, which showed a large number of collages, many of which were according to Ratcliffe inspired by the collages of Kurt Schwitters.[15]

Although initially acclaimed, art historians have noted that Colquhoun's reputation suffered during the war, a period when British surrealists such as E.L.T Mesens pamphleted against her former husband, Toni del Renzio.

A review of her 1973 exhibition in Penzance claimed:

"She has always ignored prevailing fashions in art and remained true to her beliefs and highly personal style and approach with an integrity that is to be admired. Unfortunately, as a result she has often been under-rated...'

Her major work 'La Cathedrale Engloutie' was a leading exhibit in the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition of British Surrealism, 2020[16]

Literary works

Colquhoun was also a writer.

Between 1942 and 1944, she gave a number of poetry readings at the International Arts Centre in London, an event organised by her former husband.

In 1955 she published The Crying of the Wind, a travelogue containing some stylistically surreal passages about her journeys in Ireland and interest in Celtic history. In 1961, her book The Goose of Hermogenes was published. Written in first-person narrative, the literary work was described by Paul C. Ray as a text that "recounts encounters of objective chance with their attendant shocks of recognition - encounters to produce their effect must be experienced."[17]

In the 1980s, the art historian Dawn Ades described her early literary works as "like accounts of dreams in which a stream of narrative fantasy replaces the striking juxtapositions of images in Surrealist automatic texts."[18]

She published poetry (Grimoire of the Entangled Thicket [1973], Ozmazone [1983]) and tales of her travels in Ireland and Cornwall.[19] Colquhoun also published a variety of critical writing and automatic prose on the London Bulletin, as well as essays on automatism such as 'The Mantic Stain.'[20] The article discussed automatism in the British context, leading her to give a series of lectures in institutions in the early 1950s, such as at the Oxford Art Society, Cambridge Art Society and the Working Men's Institute.

In 1953, she appeared on the BBC television show Fantastic Art.

Reception and legacy

Colquhoun gained an early reputation within the British Surrealist movement, though in later years she became better known as an occultist.[21]

Upon her death, Colquhoun left her occult work to Tate, and her other artistic belongings to the National Trust. In 2019 it was announced that more than 5,000 drawings, sketches, and commercial artworks by her had been transferred to Tate by the National Trust.[8]

Although her work has largely been discussed in terms of its connection to Surrealism, Colquhoun sometimes stated her independence from the movement. In 1939, the same year she joined the English Surrealist group, she described herself as an 'independent artist' in a review for the London Bulletin.[22]

In 2012, the scholar Amy Hale noted that Colquhoun "is becoming recognized as one of the most interesting and prolific esoteric thinkers and artists of the twentieth century".[21] Hale noted that through Colquhoun's work "we can see an interplay of themes and movements which characterizes the trajectory of certain British subcultures ranging from Surrealism to the Earth Mysteries movement and also gives us a rare insight into the thoughts and processes of a working magician."[21]

Personal life

In 1940, Colquhoun met the Russian-born Italian artist and critic Toni del Renzio in London. Although initially, it appears that Renzio gave bad reviews of Colquhoun's art when seeing her work exhibited at the A.I.A exhibition in March, he later wrote a letter to Conroy Maddox declaring that he found her to be "essentially a mystic, therefore individualist, conscious of being an artist, anxious to exhibit."[23]

They married in July 1940 and in the same year they moved into a two-storey apartment at 45a Fairfax Road, Bedford Park. Their Bedford Park studio according to Ratcliffe became an open house for friends, other artists and like-minded individuals. The marriage later became an unhappy union and Matthew Gale wrote that they were "acrimoniously divorced" in 1947. From 1945, Colquhoun lived and worked in Parkhill Road, Hampstead.

In 1957 Colquhoun moved to Cornwall, where she already owned a studio in Penzance. She remained in Cornwall until her death on 11 April 1988.[2]

Bibliography

- Salvo for Russia, 1942 (contributor)

- The Fortune Anthology, 1942 (contributor)

- The Crying of the Wind: Ireland, 1955

- The Living Stones: Cornwall, 1957

- Goose of Hermogenes, 1961

- Grimoire Of The Entangled Thicket (1973)

- Sword Of Wisdom - MacGregor Mathers and the Golden Dawn, 1975

- The Rosie Crucian Secrets: Their Excellent Method of Making Medicines of Metals Also Their Lawes and Mysteries, 1985 (provides introduction)

- The Magical Writings of Ithell Colquhoun, 2007 (edited by Steve Nichols)

- Ithell Colquhoun: Magician Born of Nature, 2009/2011 (by Richard Shillitoe)

- I Saw Water: An Occult Novel and Other Selected Writings 2014 (with an introduction and notes by Richard Shillitoe and Mark Morrisson)

- Decad of Intelligence, 2016

- Taro As Colour, 2018

- Medea's Charms: Selected Shorter Writing, 2019 (edited by Richard Shillitoe)

References

Footnotes

- Phaidon Editors (2019). Great women artists. Phaidon Press. p. 106. ISBN 0714878774.

- Remmy, Michel (2009). "Colquhoun, (Margaret) Ithell (1906–1988), painter and poet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/64737. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Morrisson 2014, p. 592.

- Gale, Matthew (1997). "Ithell Colquhoun". Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Ratcliffe, Eric (2007). Ithell Colquhoun: Pioneer Surrealist Artist, Occulist, Writer and Poet. Mandrake of Oxford. p. 35.

- Ferentinou, Victoria (2011). "Ithell Colquhoun, Surrealism, and the Occult". Papers of Surrealism (9): 2.

- Ades 1980, p. 40.

- Brown, Mark (15 July 2019). "Tate acquires vast archive of British surrealist Ithell Colquhoun". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Hale 2012, pp. 307–308.

- Hale 2012, p. 310.

- Hale 2012, p. 308.

- Hale 2012, p. 313.

- Hale 2012, p. 312.

- Portrait of the Artist: Artists' Portraits published by 'Art News & Review' 1949-1960. London: The Tate Gallery. 1989. p. 85.

- Ratcliffe, Eric (2007). Ithell Colquhoun: Pioneer Surrealist Artist, Occulist, Writer, and Poet. Oxford: Madrake of Oxford. p. 177.

- https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/about/press-media/press-releases/british-surrealism-full-press-release/

- C. Ray, Paul (1971). The Surrealist Movement in England. Cornell University Press. p. 300.

- Adès, Dawn (1980). "Notes on two women Surrealist painters: Eileen Agar and Ithell Colquhoun". Oxford Art Journal. iii/I: 36–42.

- Durozoi, Gerard (2002). History of the Surrealist Movement. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 660. ISBN 0-226-17412-3.

- Colquhoun, Ithell (1949). "The Mantic Stain". Enquiry. 2 (4): 15–21.

- Hale 2012, p. 307.

- Gaze, Delia (1997). Dictionary of Woman Artists Volume 1. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 412. ISBN 1-884964-21-4.

- Remy, Michel (1999). Surrealism in Britain. Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 226. ISBN 1859282822.

Sources

- Ades, Dawn (1980). "Notes on Two Women Surrealist Painters: Eileen Agar and Ithell Colquhoun". Oxford Art Journal. 3 (1): 36–42. doi:10.1093/oxartj/3.1.36. JSTOR 1360177.

- Hale, Amy (2012). "The Magical Life of Ithell Colquhoun". In Nevill Drury (ed.). Pathways in Modern Western Magic. Richmond, California: Conscrescent. pp. 307–322. ISBN 978-0-9843729-9-7.

- Morrisson, Mark S. (2014). "Ithell Colquhoun and Occult Surrealism in Mid-Twentieth-Century Britain and Ireland". Modernism/Modernity. 21 (3): 587–616. doi:10.1353/mod.2014.0068.

External links

- 15 paintings by or after Ithell Colquhoun at the Art UK site

- Official site

- Entry on Ithell Colquhoun at the World Religions and Spirituality Project

- Ithell Colquhoun at the Tate Gallery Archive

- Portrait of Ithell Colquhoun by Man Ray, 1932