James Smithson

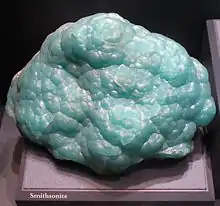

James Smithson FRS (c. 1765[1] – 27 June 1829) was an English chemist and mineralogist. He published numerous scientific papers for the Royal Society during the late 1700s as well as assisting in the development of calamine, which would eventually be renamed after him as "smithsonite". He was the founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution, which also bears his name.

James Smithson | |

|---|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project_cropped.jpg.webp) James Smithson by Henri-Joseph Johns, 1816 | |

| Born | Jacques-Louis Macie c. 1765 |

| Died | 27 June 1829 (aged 64) |

| Burial place | Smithsonian Castle, Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Chemist, mineralogist |

| Known for | Founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution |

Born in Paris, France as the illegitimate child of Hugh Percy, the 1st Duke of Northumberland, he was given the French name Jacques-Louis Macie. His birth date was not recorded and the exact location of his birth is unknown; it is possibly in the Pentemont Abbey.[2] Shortly after his birth he naturalized to Britain where his name was anglicized to James Louis Macie. He adopted his father's original surname of Smithson in 1800, following his mother's death. He attended university at Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782, eventually graduating with an honorary Master of Arts in 1786. As a student he participated in a geological expedition to Scotland and studied chemistry and mineralogy. Highly regarded for his blowpipe analysis and his ability to work in miniature, Smithson spent much of his life traveling extensively throughout Europe; he published some 27 papers in his life.[3]

Smithson never married and had no children; therefore, when he wrote his will, he left his estate to his nephew, or his nephew's family if his nephew died before Smithson. If his nephew were to die without heirs, however, Smithson's will stipulated that his estate be used "to found in Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men". He died in Genoa, Italy on 27 June 1829, aged 64. Six years later, in 1835, his nephew died without heir, setting in motion the bequest to the United States. In this way Smithson became the patron of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. despite having never visited the United States.

Early life

James Smithson was born in c. 1765 to Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland and Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie.[4] His mother was the widow of John Macie, a wealthy man from Weston, Bath.[5] An illegitimate child, Smithson was born in secret in Paris, resulting in his birth name being the Francophone Jacques-Louis Macie (later altered to James Louis Macie). In 1801 when he was about 36, after the death of his again-widowed mother, he changed his last name to Smithson, the original surname of his biological father.[6][4][7] (Baronet Hugh Smithson had changed his surname to Percy when he married Lady Elizabeth Seymour, already a baroness and indirect heiress of the Percy family, one of the leading landowning families of England).

James was educated and eventually naturalised in England.[5] He enrolled at Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782 and graduated in 1786 with an honorary MA.[8][9] The poet George Keate was a first cousin once removed, on his mother's side.

Smithson was nomadic in his lifestyle, travelling throughout Europe.[4] As a student, in 1784, he participated in a geological expedition with Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, William Thornton and Paolo Andreani to Scotland and especially the Hebrides.[10] He was in Paris during the French Revolution.[4] In August 1807 Smithson became a prisoner of war while in Tönning during the Napoleonic Wars. He arranged a transfer to Hamburg, where he was again imprisoned, now by the French. The following year, Smithson wrote to Sir Joseph Banks and asked him to use his influence to gain release; Banks succeeded and Smithson returned to England.[11] He never married or had children.[4]

In 1766, his mother had inherited from the Hungerford family of Studley, where her brother had lived up until his death.[12] His controversial legal step-father John Marshe Dickinson (aka Dickenson) of Dunstable died in 1771.[13] Smithson's wealth stemmed from the splitting of his mother's estate with his half-brother, Col. Henry Louis Dickenson.[12]

Scientific work

Smithson's research work was eclectic. He studied subjects ranging from coffee making to the use of calamine, eventually renamed smithsonite, in making brass. He also studied the chemistry of human tears, snake venom and other natural occurrences. Smithson would publish twenty-seven papers.[4] He was nominated to the Royal Society of London by Henry Cavendish and was made a fellow on 26 April 1787.[14] Smithson socialised and worked with scientists Joseph Priestley, Sir Joseph Banks, Antoine Lavoisier, and Richard Kirwan.[3]

His first paper was presented at the Royal Society on 7 July 1791, "An Account of Some Chemical Experiments on Tabasheer".[14] Tabasheer is a substance used in traditional Indian medicine and derived from material collected inside bamboo culms. The samples that Macie analysed had been sent by Patrick Russell, physician-naturalist in India.[15] In 1802 he read his second paper, "A Chemical Analysis of Some Calamines," at the Royal Society. It was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London and was the documented instance of his new name, James Smithson. In the paper, Smithson challenges the idea that the mineral calamine is an oxide of zinc. His discoveries made calamine a "true mineral".[16] He explored and examined Kirkdale Cave; his findings, published in 1824, successfully challenged previous beliefs that the fossils within the formations at the cave were from the Great Flood.[17] Smithson is credited with first using the word "silicates".[3] Smithson's bank records at C. Hoare & Co show extensive and regular income derived from Apsley Pellatt, which suggests that Smithson had a strong financial or scientific relationship with the Blackfriars glass maker.

Later life and death

Smithson died in Genoa, Italy on 27 June 1829.[4][18] He was buried in Sampierdarena in a Protestant cemetery.[18] In his will written in 1826, Smithson left his fortune to the son of his brother – that is, his nephew, Henry James Dickenson.[12] Dickenson had to change his surname to Hungerford as a condition of receiving the inheritance. In the will Smithson stated that Henry James Hungerford, or Hungerford's children, would receive his inheritance, and that if his nephew did not live, and had no children to receive the fortune, it would be donated to the United States to establish an educational institution to be called the Smithsonian Institution.[19]

Henry Hungerford died on 5 June 1835, unmarried and leaving behind no children, and the United States was the recipient.[19][20] In his will, Smithson explained the Smithsonian mission:

I then bequeath the whole of my property, . . . to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.[19]

Legacy and the Smithsonian

Later in the year of his death the United States government was informed about the bequest when Aaron Vail wrote to Secretary of State John Forsyth.[21] This information was then passed onto President Andrew Jackson who then informed Congress; a committee was organized, and after much debate the Smithsonian Institution was established by legislation.[22] In 1836 President Jackson sent Richard Rush, former Treasury Secretary, to England as Commissioner to proceed in Chancery Court to secure the funds. In 1838 he was successful and returned, accompanied by 104,960 gold sovereigns (in eleven crates) and Smithson's personal items, scientific notes, minerals, and library.[23][24] The gold was transferred to the treasury in Philadelphia and was reminted into $508,318.46.[23] The final funds from Smithson were received in 1864 from Marie de la Batut, Smithson's nephew's mother. This final amount totalled $54,165.38.[25]

On 24 February 1847 the Board of Regents, which oversaw the creation of the Smithsonian, approved the seal for the institution. The seal, based on an engraving by Pierre Joseph Tiolier, was manufactured by Edward Stabler and designed by Robert Dale Owen.[26] Although Smithson's papers and collection of minerals were destroyed in a fire in 1865, his collection of 213 books remains intact at the Smithsonian.[4][27][28] The Board of Regents acquired a portrait of Smithson dressed in Oxford University student attire, painted by James Roberts, that is now on display in the crypt at the Smithsonian Castle.[29] An additional portrait, a miniature, and the original draft of Smithson's will were acquired in 1877; they now reside in the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian Institution Archives, respectively.[30] Additional items were acquired from Smithson's relatives in 1878.[31]

The circumstances of his birth seem to have created on him a desire for posthumous fame, although he had established quite a reputation in the scientific community and lived proud of his descent.[32] Smithson once wrote:

The best blood of England flows in my veins. On my father’s side I am a Northumberland, on my mother’s I am related to kings; but this avails me not. My name shall live in the memory of man when the titles of the Northumberlands and the Percys are extinct and forgotten.[33]

Relocation of Smithson's remains to Washington

Smithson was buried just outside Genoa, Italy. The United States consul in Genoa was asked to maintain the grave site, with sponsorship for its maintenance coming from the Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Secretary Samuel P. Langley visited the site, contributing further money to maintain it and requested a plaque be designed for the grave site. Three plaques were created by William Ordway Partridge. One was placed at the grave site, a second at a Protestant chapel in Genoa, and the last was gifted to Pembroke College, Oxford. Only one of the plaques exists today. The plaque at the grave site was stolen and then replaced with a marble version. During World War II, the Protestant chapel was destroyed and the plaque was looted. A copy was eventually placed at the site in 1963.[27] The cemetery in Italy was going to be moved in 1905 for the expansion of an adjacent quarry. In response, Alexander Graham Bell, then a regent of the Smithsonian, proposed that Smithson's remains be moved to the Smithsonian Institution Building; in 1903, he and his wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, traveled to Genoa to exhume the body. A steamship departed Genoa on 7 January 1904 with the remains and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey on 20 January, where they were transferred to the USS Dolphin (PG-24) for the trip to Washington. On 25 January a ceremony was held in Washington, D.C. and the body was escorted by the United States Cavalry to the Castle.[34] When handing over the remains to the Smithsonian, Bell stated: "And now... my mission is ended and I deliver into your hands ... the remains of this great benefactor of the United States. The coffin then lay in state in the Board of Regents' room, where objects from Smithson's personal collection were on display."

Memorial

After the arrival of Smithson's remains, the Board of Regents asked Congress to fund a memorial. Artists and architects were solicited to create proposals for the monument. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Louis Saint-Gaudens, Gutzon Borglum, Totten & Rogers, Henry Bacon, and Hornblower & Marshall were some of the many artists and architectural firms who submitted proposals. The proposals varied in design, from elaborate monumental tombs that, if built, would have been bigger than the Lincoln Memorial, to smaller monuments just outside the Smithsonian Castle. Congress decided not to fund the memorial. To accommodate the fact that the Smithsonian would have to fund the memorial, they used the design of Gutzon Borglum, which suggested a remodel of the south tower room of the Smithsonian Castle to house the memorial surrounded by four Corinthian columns and a vaulted ceiling. Instead of the tower room, a smaller room (at the time it was the janitor's closet) at the north entrance would house an Italian-style sarcophagus.[35]

On 8 December 1904 the Italian crypt was shipped, in sixteen crates from Italy. It travelled on the same ship that the remains of Smithson travelled on. Architecture firm Hornblower & Marshall designed the mortuary chapel, which included marble laurel wreaths and a neo-classical design. Smithson was entombed on 6 March 1905. His casket, which had been held in the Regent's Room, was placed into the ground underneath the crypt. This chapel was to serve as a temporary space for Smithson's remains until Congress approved a larger memorial. However, that never happened, and the remains of Smithson still lie there today.[36]

Ancestors

| 8. Sir Hugh Smithson, 3rd Bart., of Stanwick, (1657–1733)[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Langsdale Smithson[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Hon. Elizabeth Langdale[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland | |||||||||||||||

| 10. William Reveley of Newby Wiske (1662–1725)[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Philadelphia Reveley[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 11. Margery Willey | |||||||||||||||

| 1. James (Jacques) Louis Macie Smithson | |||||||||||||||

| 12. John Keate Esq.[38] | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Lt. John Hungerford Keate Esq. (1709-c1755)[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 13. Frances Hungerford[38] | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie (1728–1800) | |||||||||||||||

| 14. Henry Fleming DD, (1659–1728),[38] Rector of Grasmere | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Penelope Fleming (c1711-1764)[37] | |||||||||||||||

| 15. Mary Fletcher | |||||||||||||||

References

- "Smithsonian History, James Smithson". Smithsonian Institution Archives Website. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Ewing, Heather (2010). The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. AC Black. Ch. 1, note 35.

- Colquhoun, Kate (31 May 2007). "A very British pioneer". The Telepgrah. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "James Smithson". Smithsonian History. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). Birth of James Smithson. New York: De Vinne Press. pp. 1, 9.

- As early as December 1800, Macie began using the name Smithson, by signing the Royal Society of London visitor register as James Smithson.

- "James Macie Changes His Name to Smithson". Public Records Office, Great Britain. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "James Smithson Enrolls at Oxford". Record Unit 7000, Box 5. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Goode, George Brown (1880). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. pp. 10–11.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 10.

- "Smithson Held as a Prisoner of War". James Smithson Collection, 1796–1951. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 22.

- His mother married him in the autumn of 1768, see Dickenson v. Macie (London, 1771), The Law Library, volume XXII, Philadelphia, 1838.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 11.

- Macie, ames Louis Macie, Esq. (1791). "An Account of Some Chemical Experiments on Tabasheer". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 81: 368–388. doi:10.1098/rstl.1791.0025. S2CID 186214539.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: Di Vinne Press. pp. 12–13.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. pp. 13–14.

- Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835–1899, Vol. 1, 1835–1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 13.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. pp. 19–21.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 25.

- Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835–1899, Vol. 1, 1835–1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 8–9.

- Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835–1899, Vol. 1, 1835–1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 125.

- "Smithson's Legacy and Effects Arrive in NY". Chronology of Smithsonian History. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 30.

- Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835–1899, Vol. 1, 1835–1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 116–117.

- Rhees, William J. (1879). Journals of the Proceedings of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1846–76, Reports of Committees, Statistics, Etc. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 445–446.

- Stamm, Richard E. "The Italian Grave Site". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington And the Search for a Proper Memorial. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "A Man of Science". From Smithson to Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Purchase of Smithson Portrait". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Smithson Portrait and Papers Purchased". Record Unit 7000, Box 3, Folder 7. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Smithson Artifacts Obtained from de la Batut". Record Unit 7000, p. Box 3, Folder 7. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Appleton's Cyclopædia of American Biography, Vol. V, Pag. 598. D. Appleton & CO., New York, 1887.

- Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. LIII, Pag. 173. Edited by Sidney Lee. Smith, Elder & CO, London 1898, The Macmillan CO.

- Stamm, Richard E. "The Exhumation and Journey to America". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Stamm, Richard E. "The Search for a Proper Memorial". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Stamm, Richard E. "Smithson's Crypt". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage. 2 (107th ed.). Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd. pp. 2942–43.

- Burke, Bernard (1866). A Genealogical History of the Dormant: Abeyant, Forfeited, and Extinct Peerages of the British Empire. Harrison. p. 291.

Further reading

- Works by James Smithson

- Works about James Smithson

Articles

- Bird Jr., William L., William L. Bird, Jr. "A Suggestion Concerning James Smithson's Concept of 'Increase and Diffusion.'" Technology and Culture Vol. 24 No. 2 (April 1983): 246–255.

- Burleigh, Nina (Summer 2012). "Digging Up James Smithson: Alexander Graham Bell traveled to Italy at the turn of the 20th century on an audacious mission to rescue the remains of the man whose legacy endowed the Smithsonian Institution". American Heritage. 62 (2).

- CNN, "How a Mysterious Englishman's Fortune Founded the Smithsonian". 8 May 2000.

- Larner, Jesse (21 December 2003). "Foreign Motivations: How a Former President and an English Scientist Gave Us the Smithsonian (review of Nina Burleigh's The Stranger and the Statesman)". San Francisco Chronicle.

Books

- Bello, Mark; William Schulz; Madeleine Jacobs; Alvin Rosenfeld (eds.) (1993). The Smithsonian Institution, a World of Discovery : An Exploration of Behind-the-Scenes Research in the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities. Washington, D.C.: Distributed by Smithsonian Institution Press for Smithsonian Office of Public Affairs. ISBN 1-56098-314-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bolton, Henry Carrington (1896). The Smithsonian Institution : Its Origin, Growth, and Activities. New York, N.Y.

- Burleigh, Nina (2003). The Stranger and the Statesman : James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America's Greatest Museum, The Smithsonian. New York, N.Y.: Morrow. ISBN 0-06-000241-7.

- Ewing, Heather (2007). The Lost World of James Smithson : Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. USA: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-59691-029-4.

- Goode, George Brown (ed.) (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896 : The History of its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) Reprinted as Goode, George Brown (ed.) (1980). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896. New York, N.Y.: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-12584-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gurney, Gene (1964). The Smithsonian Institution, a Picture Story of its Buildings, Exhibits, and Activities. New York, N.Y.: Crown.

- Hellman, Geoffrey T. (1966). The Smithsonian : octopus on the Mall. Philadelphia; New York: J.B. Lippincott Company.

- Karp, Walter (1965). The Smithsonian Institution; an Establishment for the Increase & Diffusion of Knowledge among Men. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Rhees, William Jones (comp. & ed.) (1901). The Smithsonian Institution : Documents Relative to its Origin and History, 1835–1889. Washington, D.C.: G.P.O. Reprinted as Rhees, William Jones (ed.) (1980). The Smithsonian Institution, 1835–1899 (2 vols.). New York, N.Y.: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-12583-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Smithson. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: James Smithson |

- Smithson's story and will Smithsonian Institution

- Smithson's biographical details from the Royal Society of London

- Smithson's Library at the Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- James Smithson at LibraryThing by the Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- Remembering James Smithson from Around the Mall