Jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots

The jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587) are mainly known through the evidence of inventories held by the National Archives of Scotland.[1]

Collection of a queen

Mary, Queen of Scots inherited personal jewels belonging to her father, James V. For a time, the Earl of Arran was ruler of Scotland as regent. In 1556, after her mother Mary of Guise had become regent, Arran returned a large consignment of royal jewels to the young queen in France.[2][3] Mary had jewels repaired and refashioned by a Parisian jewellers Robert Mangot who made paternoster beads and Mathurin Lussault, who also provided gloves, pins, combs and brushes.[4] Lussault himself was a patron of the sculptor Ponce Jacquiot, who designed a fireplace for the goldsmith.[5] Her clothes were embroidered with jewels, a white satin skirt front and sleeves featured 120 diamonds and rubies, and coifs for her hair had gold buttons or rubies, sewn by her tailor Nicolas du Moncel in 1551.[6]

She was betrothed to the French prince Francis, and was given jewels to wear which were regarded as the property of the French crown. Her jewelled appearance at their wedding included necklaces with a pendant of "incalculable value."[7][8] Her mother-in-law, Catherine de' Medici, gave her the necklaces which she had commissioned from goldsmiths in Lyon and Paris.[9] After Francis died in December 1560, Mary had to return many of the French crown jewels to Claude de Beaune, Dame du Gauguier, a lady-in-waiting and treasurer to Catherine de' Medici.[10][11]

Queen Elizabeth had proposed sending her portrait to Mary in Scotland in January 1561, but her painter was unwell. Mary, Queen of Scots mentioned to the ambassador Thomas Randolph that she would send Elizabeth a ring with a diamond made like a heart by the envoy who brought the portrait, and after the portrait failed to materialise, in June 1561 she told Randolph she would send the ring with some verses she had written herself.[12] In October 1564 Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox arrived at the Scottish court, and gave Mary a "marvellous fair and rich" jewel, a clock and dial, and a looking glass set with precious stones in the "4 metals". He gave diamond rings to several courtiers and presents to the queen's four Maries.[13] The English ambassador Thomas Randolph observed Mary playing dice with Lennox, wearing a mask after dancing, and losing a "pretty jewel of crystal well set in gold" to the earl.[14]

In July 1565 Mary paid a French goldsmith in Edinburgh, Ginone Loysclener, £76 Scots. This was probably for gifts at her wedding to Lord Darnley.[15] Soon after they faced a rebellion now known as the Chaseabout Raid. In need of money, it was said they tried to pawn some of her jewels in Edinburgh for 2,000 English marks, but no-one would lend this sum.[16] When Mary, Queen of Scots was pregnant in 1566 she made an inventory of her jewels, leaving some as permanent legacies to the crown of Scotland, and others to her relations, courtiers, and ladies-in-waiting.[17] Mary Livingston and Margaret Carwood helped her and signed the documents.[18]

If Mary had died in childbirth, one Scottish lady in waiting, Annabell Murray, Countess of Mar and her daughter Mary Erskine would have received jewels including a belt of amethysts and pearls, a belt of chrysoliths with its pendant chain, bracelets with diamonds, rubies and pearls, pearl earrings, a zibellino with a gold marten's head, and yet another belt with a miniature portrait of Henri II of France.[19] An Edinburgh goldsmith John Mosman had made a gold marten's head for her mother, Mary of Guise, in 1539, and the queen had several.[20]

The queen's four year old nephew Francis Stewart, son of Lord John Stewart, would have had several sets of gold buttons and aiglets, and a slice of unicorn horn mounted on silver chain, used to test for poison.[21] Mary wanted the Earl of Bothwell to have a jewel for a hat with a mermaid set with diamonds and a ruby, which she kept close by her in her cabinet.[22]

Mary safely gave birth to Prince James at Edinburgh Castle. According to Anthony Standen a diamond cross was fixed to James's swaddling clothes in the cradle.[23] His christening was held at Stirling Castle on 17 December 1566. Mary gave presents of her jewels as diplomatic gifts. The Earl of Bedford represented Queen Elizabeth at the baptism and was guest of honour at the banquet and masque.[24] She gave him a gold chain set with pearls, diamonds, and rubies.[25] According to James Melville of Halhill she also gave Christopher Hatton a chain of pearls and a diamond ring, a ring and a chain with her miniature picture to Henry Carey, and gold chains to five English gentlemen of "quality".[26]

Regent Moray and the queen's jewels

In 1567 Mary, Queen of Scots was deposed and imprisoned in Lochleven Castle, and her half-brother, James Stewart, became the ruler of Scotland and was known as Regent Moray. His secretary John Wood and Mary's wardrobe servant Servais de Condé made inventories of her clothes and jewels.[27]

Regent Moray and the treasurer Robert Richardson raised loans with jewels as security and sold some pieces with precious stones to Edinburgh merchants.[28] Robert Melville arranged with Valentine Browne, treasurer of Berwick, for loans secured on the jewels.[29] John Wood and Nicoll Elphinstone marketed Mary's jewels in England.[30] Nicoll Elphinstone sold Mary's pearls to Queen Elizabeth, despite offers from Catherine de' Medici.[31][32] The chains of pearls, some as big as nutmegs,[33] are thought to be represented in Elizabeth's "Armada Portrait".[34]

Other jewels sold by Regent Moray ended up in the hands of the widows of two merchants who dealt with him. Helen Leslie, the "Goodwife of Kinnaird", was the widow of James Barroun, who had loaned money to Moray. She married James Kirkcaldy, whose brother, Moray's friend William Kirkcaldy of Grange, unexpectedly declared for Mary in 1570.[35]

Helen, or Ellen, Achesoun, a daughter of the goldsmith John Achesoun,[36] was the widow of William Birnie, a merchant who had bought the lead from the roof of Elgin Cathedral in 1568 expecting a lucrative deal in scrap metal.[37] Achesoun and Birnie had lent Moray £700 Scots and taken as security some of Mary's "beltis and cousteris". The "couster", or in French a "cottouere" or "cotiere", was the gold chain that descended from a woman's belt with its terminal pendant. One of these was described in Scots as, "ane belt with ane cowter of gold and ceyphres (ciphers) and roissis quheit and reid inamelit (roses enamelled white and red), contenand knoppis and intermiddis (entredeux) with cleik (clasp) and pandent 44 besyd the said pandent."[38]

After Birnie died, Achesoun married Archibald Stewart, a future Provost of Edinburgh and friend of John Knox. A silver mounted "mazer" or cup made for the couple, engraved with their initials, survives.[39][40] Despite their Protestant credentials, they became financial backers of Mary's cause in Scotland by lending money to William Kirkcaldy, on the security of more of the queen's jewels.[41]

After Mary escaped from Lochleven in May 1568 and made her way to England, the jewel sales were halted. Most of the remaining pieces which Mary had left behind were kept in a coffer in Edinburgh Castle. The Parliament of Scotland exonerated Regent Moray from selling Mary's jewels but Queen Elizabeth, according to Mary's request, wrote to ask him not to sell her jewels in October 1568. Moray agreed and claimed he and his friends had not personally been "enriched worth the value of a groat of any of her goods".[42]

After Moray was assassinated in January 1570, Mary wrote from Tutbury and Sheffield Castle to his widow, Agnes Keith, asking for "our H", the "Great H of Scotland" and other pieces. Agnes Keith kept these jewels. Regent Moray had taken them to England and brought them back unsold. His successor Regent Lennox wanted them, while the Earl of Huntly wrote for them for Mary, Agnes Keith did not oblige.[43] The "Great H" or "Harry" may have been the priceless pendant which Mary had worn at her first wedding in 1558.[44]

Regent Lennox said in August 1570 he would not borrow money on the security of Mary's jewels, and promised to make an inventory of her things, her gowns and furnishings, which were safe in Edinburgh castle, apart from the tapestry hanging at Stirling Castle.[45] During the "Lang Siege" of Edinburgh Castle, the last action of the Marian Civil War, the Captain of the castle, William Kirkcaldy of Grange gave jewels to supporters of Mary as pledges for loans they gave him to pay his garrison.[46] The goldsmiths James Mossman and James Cockie valued the jewels as pledges for loans, and Mossman loaned his own money and accepted jewels as security.[47] Several documents concerning the jewels and loans survive from this time, including a note about Mary's marriage ring, which was in the hands of Archibald Douglas.[48]

Regent Morton and the jewels

.jpg.webp)

The siege caused great suffering in Edinburgh. The new ruler of Scotland Regent Morton made strenuous efforts to recover the jewels after the castle surrendered on 28 May 1573.[49] As English and Scottish soldiers entered the castle, James Mosman gave his share of the queen's jewels to Kirkcaldy, wrapped in an old cloth or "evill favoured clout", and he put them in a chest in his bedchamber.[50] The English commander at the siege, William Drury recovered the jewel coffer from a vault and redeemed some jewels from lenders including Helen Leslie, Lady Newbattle and Helen Achesoun. They came to his lodging at Leith where Kirkcaldy was held.[51] William Kirkcaldy, his brother James, James Cockkie, and James Mossman were executed by hanging on 3 August 1573.[52]

Morton obtained the records of the loans and pledges made by Kirkcaldy, and later wrote of his pleasure at this find to the Countess of Lennox.[53] Kirkcaldy made a statement about the jewels for the benefit of William Drury. Amongst the papers from the castle, Kirkcaldy had written in the margins of an inventory gifts made, or to be made, to Margery Wentworth, Lady Thame, widow of John Williams, Master of the Jewels, and wife of William Drury. Kirkcaldy had blotted out some of these marginal notes, and now signed a statement that Lady Thame had refused any gifts of Mary's jewels from him back in April 1572 when she was staying at Restalrig.[54]

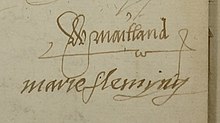

Mary Fleming, who had helped make this inventory of the jewels with her husband William Maitland and Lady Seton, was ordered to return a chain or necklace of rubies and diamonds.[55] Agnes Gray, Lady Home surrendered jewels which had been her security for a loan of £600 Scots.[56] The lawyer Robert Scott returned a "carcan" or garnishing, circled about with pearls, rubies and diamonds.[57] On 28 July the triumphant Regent sent Mary's gold buttons and pearl-set "horns" to Annabell Murray at Stirling Castle to be sewn on the king's clothes.[58] On 3 August Morton sent a copy of Kirkcaldy's inventory to the Countess of Lennox, in the hope that she could get all the jewels still in Drury's hands and now in Berwick sent to him.[59]

Morton wrote to Countess of Lennox again later in August, asking for a progress report. Ninian Cockburn, the bearer of his letter, had delivered some jewels from Archibald Douglas to Valentine Browne, treasurer of Berwick.[60] In October 1573 Morton sent money to Berwick to redeem one of the queen's garnishings, comprising a pair of headbands and a necklace of "roses of gold" set with diamonds.[61] Robert Melville was interrogated about the jewels in October.[62] Gilbert Edward, the page of Valentine Browne, the treasurer of Berwick, ran away from his master and stole several jewels, including a jewelled mermaid.[63] Browne's mermaid was described in similar terms to an "ensign" Mary had inherited from her father, James V.[64][65]

_(attributed_to)_-_Portrait_of_a_Lady%252C_called_Lady_Helen_Leslie%252C_Wife_of_Mark_Ker_-_NG_1939_-_National_Galleries_of_Scotland.jpg.webp)

Morton had a prolonged negotiation with Moray's widow, Agnes Keith, now Countess of Argyll, for the return of the diamond and cabochon ruby pendant called the "Great H of Scotland" and other pieces.[66] Unsurprisingly, Mary wrote again to the countess asking her to return the jewels to her instead. Agnes Keith claimed the jewels were security for her late husband's unpaid expenses as Regent, but she gave them to Morton in March 1575.[67]

Morton resigned the regency in March 1579, and his half-brother, George Douglas of Parkhead, made an inventory of royal jewels, her costume and her dolls, furnishings, and library.[68]

Jewels with political messages

Mary Queen of Scots wrote from Sheffield Castle in 1574 and 1575 to her ally, the Archbishop of Glasgow in Paris asking him to commission jewelry for her. She wanted gold lockets with her portrait to send to her friends in Scotland. As a gift for Queen Elizabeth, Mary wanted bracelets or a pendant or gold mirror to hang from a belt. This would be decorated with her cipher or initials conjoined with Elizabeth's, and with other motifs, emblems, or inscriptions, according to the "device" made by her uncle, the Cardinal of Lorraine. She also asked for a gold belt and necklace as a present for the daughter of her chancellor, Gilles du Verger.[69][70] The portraits, to be distributed as keepsakes for her supporters, may have been her profile cut in cameo. Several examples exist, and one is said to have been Mary's gift to Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk.[71][72]

While she was at Chatsworth in September 1578 Mary wrote to the Archbishop again, sending a "device", a description of the concept and theme for a jewel she wanted to be made in gold and enamel as a gift for her son, James VI.[73][74] In 1570 the Countess of Atholl, and her friends, known as the "Witches of Atholl", had commissioned a jewel which referred directly to the succession to the crown of England.[75] The surviving "Lennox Jewel" now in the Royal Collection is a propaganda jewel of this type, thought to have been commissioned by Mary's mother-in-law Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox.[76][77]

James VI

James VI gave several of his mother's jewels to his favourite Esmé Stewart in October 1581, including the "Great H" and a gold cross set with seven diamonds and two rubies.[78] In September 1584 a German travel writer Lupold von Wedel saw James, who was staying at Ruthven Castle, wearing this cross on his hat ribbon in St John's Kirk in Perth.[79] In October the valet John Gibb returned the cross to the Master of Gray, the newly appointed Master of the Royal Wardrobe.[80] It was probably the same diamond and ruby cross that his grandmother, Mary of Guise had pawned to John Home of Blackadder for £1000 when she was Regent of Scotland, and Mary, Queen of Scots had redeemed.[81]

James Stewart, Earl of Arran and Elizabeth Stewart, Countess of Arran directed the Master of Gray to dress the king in his exiled mother's jewels. He had one of the queen's head garnishings of diamonds, pearls, and rubies broken up to embroider a cloak for the young king, during the visit of the English ambassador Edward Wotton in May 1585. Some of the gold settings were put on a bonnet string.[82]

On 3 February 1603 James VI of Scotland gave James Sempill of Beltries, a son of Mary Livingston, a jewel which had belonged to Mary as a reward for his good service and faithful conduct in diplomatic negotiations in England. The jewel was a carcatt (a necklace chain) with a diamond in one piece and a ruby in another, with a tablet (a locket) set with a carbuncle of a diamond and ruby, set around with diamonds.[83]

In 1604 King James had the "Great H" dismantled and the large diamond was used in the new "Mirror of Great Britain" which James wore as a hat badge.[84]

Mary in England

When Mary was recently arrived in England at Bolton Castle in July 1568, she asked a dependant of the border warden Lord Scrope called Garth Ritchie to ask Lord Sempill's son, John Sempill of Beltrees, the husband of Mary Livingston, to send her the jewels in their keeping. Garth Ritchie managed to bring some of the queen's clothes and a cloth of estate from Lochleven Castle, but Regent Moray would not give Sempill permission to send any jewels.[85] Regent Lennox would later ask John Sempill to return jewels and furs belonging to Mary to him, including sable and marten furs or zibellini. Mary declared that the jewels Sempill had were gifts from the King of France and did not pertain to Scotland.[86]

Mary had some jewelry and precious household goods with her in England. Inventories were made at Chartley in 1586 of pieces in the care of Jean Kennedy,[87] and at Fotheringhay in February 1587.[88] She usually wore a cross of gold and pearl earrings. Another gold cross was engraved with the Mysteries of the Passion.[89]

A list of items taken from Mary Queen of Scots in 1586 includes a looking glass decorated with miniature portraits of Mary and Elizabeth, and a little chest decorated with diamonds, rubies, and pearls. This may represent furniture for the queen's dressing table. There was also a gold pincase to wear on a girdle and some items of costume including a black velvet cap with a green and black feather.[90] A longer list of the queen's jewels was made at Chartley in 1586, and after her execution.[91] There were two porcelain spoons, one silver, one gold, a bezoar stone set in silver, and a slice of unicorn horn set in gold with a gold chain. There was a charm stone against poison, as big as a pigeon's egg, with a gold cover, and another stone to guard against melancholy. There were boxes of costly terra sigillata and powdered mummy, coral, and pearls.[92]

The Eglinton parure

A necklace from the collection of the Earls of Eglinton is traditionally believed to have been Mary's gift to Mary Seton. The piece includes "S-shaped snakes in translucent dark-green enamel". It was divided into two in the 17th-century, one part is displayed at the National Museum of Scotland and the other, held by the Royal Collection, at Holyrood Palace. These may have been pieces of a longer chain or cotiere.[93][94][95]

Later, Anne of Denmark is known to have given jewelry to her maid of honour Anne Livingstone including a chain (or belt) comprising 96 pieces; "22 of greane snakes sett with two small pearles", and 43 pieces shaped "like S with three of sparks of rubies". This was perhaps the item that Mary, Queen of Scots had given to Mary Seton. The gifts were made to Anne Livingstone when she left court for Scotland in 1607, and on her marriage to Mary Seton's great-nephew, Alexander Seton of Foulstruther.[96]

The necklace and a painting once attributed to Hans Holbein were said to have come into the Eglinton family from the Setons in 1611, when Alexander Seton of Foulstruther, a son of Robert Seton, Earl of Winton and Margaret Montgomerie, became Earl of Eglinton.[97] He changed his surname to Montgomerie, and married Anne Livingstone, the childhood companion of Elizabeth of Bohemia and favourite of Anne of Denmark.[98]

Mary's biographer Agnes Strickland visited Eglinton Castle in 1847 and Theresa, Lady Eglinton lent her the necklace. Strickland's assistant Emily Norton made a drawing of it.[99] In 1894 George Montgomerie, 15th Earl of Eglinton rediscovered the necklace in the muniment room at Eglinton.[100] He sold it by auction, for the benefit of his sisters, according to his father's will. By this time the jewel had long been divided into at least two pieces, another chain with green serpents was at Duns Castle in the possession of the Hay family.[101] This section of the necklace came to the Hay family when Elizabeth Seton married William Hay of Drumelzier in 1694. The moiety from Eglinton was presented by Lilias Countess Bathurst to Queen Mary in 1935.[102]

Golf and the Seton necklace

Mary, Queen of Scots and Lord Darnley played games like bowls and wagered high stakes, and in April 1565 when Mary Beaton won at Stirling Castle, Darnley gave her a ring and a brooch set with two agates worth fifty crowns.[103] A similar story is told of the Seton necklace, that the queen gave it to Mary Seton after she won a round of golf at Seton Palace. Mary certainly played golf at Seton, and in 1568 her accusers said she had played "pall-mall and golf" as usual at Seton in the days after Darnley's death.[104]

Mary Seton's golf connection was publicised around the time of the auction in Golf Magazine (March 1894), followed up by Robert Seton's 1901 Golf Illustrated article, 'Archery and Golf in Queen Mary's Time'.[105]

The Penicuik jewels

These pieces are traditionally believed to have belonged to Geillis Mowbray of Barnbougle, who served Mary, Queen of Scots in England and was briefly betrothed to her apothecary, Pierre Madard.[106] They were heirlooms in the family of John Clerk of Penicuik. They consist of a necklace, locket and pendant. The necklace has 14 large filigree open-work "paternoster" beads which could be filled with perfumed musk.[107] The locket has tiny portraits of woman and a man, traditionally identified as Mary and James VI. The gold pendant set with pearls may have been worn with the locket. The Penicuik jewels are displayed at the National Museum of Scotland.[108] Mary bequeathed Geillis Mowbray jewels, money, and clothes, including a pair of gold bracelets, a crystal jewel set in gold, and a red enamelled "oxe" of gold. She kept Mary's virginals, a kind of harpsichord, and her cittern.[109]

The fundraiser and purchase of the Penicuik jewels by the museum and their history were described in 1923 by Walter Seton. He explains the descent of the jewels in the Clerk family. Geillis Mowbray married Sir John Smith of Barnton. Their daughter, Geillis Smith married Sir William Gray of Pittendrum, and their daughter Mary Gray married the successful merchant John Clerk,[110] who bought the Penicuik estate in 1646.[111] Geillis Mowbray's son John Smith of Grothill and Kings Cramond was Provost of Edinburgh.

When William Kirkcaldy of Grange was about to be executed, Geillis Mowbray's father, the Laird of Barnbougle, who was now Kirkcaldy's brother-in-law, wrote to Regent Morton to plead for his life, offering money, service, and royal jewels worth £20,000 Scots.[112] In 1603 Geillis' half-brother Francis Mowbray fell to his death from Edinburgh Castle.[113]

The inventories

Most of the inventories and papers listing the jewels are held by the National Records of Scotland. They were written in French or in Scots. Some were published by Thomas Thomson in 1815,[114] and others by Joseph Robertson in 1863.[115] A 1906 work by Andrew Lang attempted to link jewelry and costume depicted in alleged portaits of Mary, Queen of Scots with the inventory descriptions.[116]

Original documents include:

- Inventory of heirloom jewels received by Mary, Queen of Scots from the former Regent Arran, 3 June 1556. Includes a cupid with a ruby heart,[117] a jewelled dagger given to James V by Francis I,[118][119] and a mermaid with a diamond mirror and a ruby tail.[120][121]

- 'Memoir of the Crown', list of jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots with others in her possession belonging to the French crown, 1550s, National Records of Scotland, E35/4

- Inventory of the jewel coffer in Edinburgh Castle, August 1571, National Records of Scotland E35/9/4, signatures described by Regent Morton.[122]

- Declaration by William Kirkcaldy of Grange about the jewels, 13 June 1573.[123]

- Answers of William Kirkcaldy of Grange, 11 July 1573, National Records of Scotland, E35/11/30.

- Deposition of William Kirkcaldy of Grange, 3 August 1573, British Library Add. MS 32091.

- Inventory of jewels recovered after the siege by William Drury, National Archives TNA, SP 52/25 fol. 146.[124][125]

- Copy of William Drury's inventory, Hatfield, with differences including "... a ring with a great diamond, which was the Queen's marriage ring. One other great diamond."[126]

- Answers of Robert Melville, 19 October 1573 (formerly Hopetoun MSS), British Library Add. MS 3,351 fol. 119.[127][128]

- Inventory of Mary's goods in Edinburgh Castle, 1578, includes her books, and her dolls or "pippens",[129] British Library, Harley MS 4637 fol. 142.[130]

- Inventory made at Fotheringhay after the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, National Archives TNA, SP 53/21 fol. 39.[131]

References

- John Duncan Mackie, 'Queen Mary's Jewels', Scottish Historical Review, 18:70 (January 1921), pp. 83–98.

- HMC 11th Report, Part VI: Duke of Hamilton (London, 1887), pp. 41–2

- Jane Stoddart, The girlhood of Mary Queen of Scots from her landing in France to her departure (London, 1908), pp. 394-6

- Thierry Crépin-Leblond, Marie Stuart: le destin français d'une reine d'Écosse, (Paris, 2008), pp. 56, 70: Alphonse de Ruble, La première jeunesse de Marie Stuart, (Paris, 1891), 37-40, 297: See also National Records of Scotland E35/4.

- Contract Lussault Jacquiot, Archives Nationales: MC/ET/CXXII/1395

- Alphonse Ruble, La première jeunesse de Marie Stuart (Paris, 1891), pp. 287-8, 297.

- William Bentham, Ceremony at the marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots (London, 1818), p. 6.

- Discours du grand et magnifique triumphe faict au mariage du Francois de Valois Marie d'Estruart roine d'Escosse (Paris, 1558)

- Germain Bapst, Histoire des joyaux de la couronne de France (Paris, 1889), p. 55 fn. 2

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), pp, 191-201: See also NRS E35/4: Susan Broomhall, 'Gender, Materiality, Performativity and Catherine de' Medici', Elise M. Dermineur, Åsa Karlsson Sjögren, Virginia Langum, Revisiting Gender in European History, 1400–1800 (New York, 2018).

- Jane Stoddart, The girlhood of Mary Queen of Scots from her landing in France to her departure (London, 1908), pp. 308, 315-7

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. 588 no. 1063, 603 no. 1077, 632-3 no. 116.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. 85-6.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 88.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer: 1559-1566, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1916), pp. liv, 374.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1563-1569, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 223.

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), pp. xxx–lix, 93–124

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), pp. 115, 121, 123.

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), p. xliii, 105-8, 119.

- Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 265.

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), pp. xxxix-xli, 110-1, 123.

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), p. 222.

- Mrs Hubert Barclay, The Queen's Cause: Scottish Narrative, 1561-1587 (London, 1938), p. 151: Anthony Standen's "Relation" is in The National Archives, TNA SP14/1/237.

- Felicity Heal, 'Royal Gifts and Gift Exchange in Anglo-Scottish Politics', in Steve Boardman, Julian Goodare, Kings, Lords and Men in Scotland and Britain 1300–1625, Essays in Honour of Jenny Wormald (Edinburgh, 2014), p. 292.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1563-1569, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 310.

- Thomas Thomson, James Melville: Memoirs of his own life (Edinburgh, 1827), p. 172.

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), pp. 179, 185–6: HMC 6th Report: Earl of Moray (London, 1877), p. 672.

- HMC 6th Report: Earl of Moray (London, 1877), p. 643.

- William Fraser, The Melvilles, Earls of Melville and the Leslies, Earls of Leven, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1890), p. 92

- Historical Manuscripts Commission 6th Report: Earl of Moray (London, 1877), p. 643.

- Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 129–130.

- Karen Raber, 'Chains of Pearls: Gender, Property, Identity', in Bella Mirabella ed, Ornamentalism: The Art of Renaissance Accessories (University of Michigan, 2011), pp. 159-180.

- Diana Scarisbrick, Tudor and Jacobean Jewellery (London, 1995), p. 17 'nutmegs' is a translation of 'noix muscades' from Labanoff, 7, p. 132.

- Lisa Hopkins, Writing Renaissance Queens: Texts by and about Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots (Delaware, 2002), p. 21.

- David Laing, Works of John Knox, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1848), p. 322-3: Harry Potter, Edinburgh Under Siege: 1571-1573 (Stroud, 2003), p. 45.

- G. How, 'Canongate Goldsmiths and Jewellers', Burlington Magazine, 74:435 (June 1939), p. 287.

- Register of the Privy Council, vol. 1, pp. 608-10.

- HMC 6th Report: Earl of Moray (London, 1877), pp. 643-4

- 'The Galloway Mazer', National Museums of Scotland

- Andrea Thomas, Glory and Honour: The Renaissance in Scotland (Edinburgh, 2013), p. 72.

- Michael Lynch, Edinburgh and the Reformation (Edinburgh, 1981), pp. 129, 147.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 514 no. 831, 517-8 no. 838 (modernised here).

- HMC 6th Report: Moray (London, 1877), pp. 638, 653: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 3, pp. 417, 427.

- Agnes Strickland, Life of Mary, Queen of Scots, vol. 1 (London, 1873), p. 30.

- William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1903), p. 303.

- Michael Lynch, Edinburgh and the Reformation, (Edinburgh, 1981), pp. 138–9, 145, 147.

- Bruce Lenman, 'Jacobean Goldsmith-Jewellers as Credit-Creators: The Cases of James Mossman, James Cockie and George Heriot', Scottish Historical Review, 74:198 (1995), pp. 159–177.

- A. Francis Steuart, Seigneur Davie: A Sketch Life of David Riccio (London, 1922), p. 114 quoting NRS E35/11/4.

- George R. Hewitt, Scotland Under Morton: 1572-1580 (John Donald; Edinburgh, 1982), pp. 40-2.

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), p. clii: NRS E35/11/30 has "pouch".

- William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-4, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), pp. 584-5.

- Historie of James the Sext (Edinburgh, 1804), p. 237.

- CSP Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 604: NRS E35/11.

- Robertson (1863), p. clii-cliv, the inventory is now NRS E35/9/4.

- Charles Thorpe McInnes, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland: 1566–1574, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1970), p. 355: Thomas Thomson, Collection of Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), pp. 193–4: John Hill Burton, Register of the Privy Council, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1878), pp. 246-7

- Thomson (1815), p. 195: Register of the Privy Council, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1878), p. 247.

- Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, K.M. Brown et al eds (St Andrews, 2007-2020), 1581/10/117. Date accessed: 1 October 2020

- Thomson (1815), pp. 277-8.

- CSP Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 604.

- CSP Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 604.

- George R. Hewitt, Scotland Under Morton: 1572-1580 (John Donald; Edinburgh, 1982), p. 40: Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1970), p. 364.

- William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-4, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), pp. 615-23.

- Thomas Astle, The Antiquarian Repertory, vol. 1 (London, 1807), p. 23

- HMC 11th Report, Part VI: Duke of Hamilton (London, 1887), p. 41.

- Thomson (1815), p. 68, James V had a black bonnet with a 'tergat' of a mermaid, her tail of diamonds with a ruby and a table diamond, sewn with gold and jewelled sets.

- Thomson (1815) pp. 195–200.

- Amy Blakeway, Regency in Sixteenth-Century Scotland (Woodbridge, 2015), p. 90.

- Thomas Thomson, Collection of Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), pp. 201-272, (the google scanned images omit pp. 256-257). Another version of this inventory, with slight differences and contemporary annotation, is held by the British Library, Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 383 no. 327 citing Harley MS 4637.

- A. Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stewart, vol. 4 (London, 1852), pp. 214-5, 256, 269.

- John Guy, Queen of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart (Houghton Mifflin, 2004), p. 438.

- Joan Evans, A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870 (London, 1970), p. 199, pl. 92.

- Cameo jewel, Portland Collection, The Jewellery Editor

- Maria Hayward, Stuart Style (Yale, 2020), pp. 215-6.

- A. Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stewart, vol. 5 (London, 1852), p. 66.

- Julian Goodare, The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester, 2002), p. 58: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 3 (London, 1903), pp. 315, 361-2, 368-70.

- Maria Hayward, Stuart Style (Yale, 2020), p. 203.

- 'The Lennox Jewel', RCIN 28181

- Thomson (1815), p. 307.

- Thomson (1815), p. 308: Gottfied von Bülow, 'Journey Through England and Scotland made by Lupold von Wedel', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 9 (London, 1895), p. 245

- Thomson (1815), p. 314.

- Accounts of Treasurer, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1915), pp. xxxi-xxxii, 237.

- Thomas Thomson, Collection of Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), p. 320.

- David Masson, Register of the Privy Council: 1599–1604, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1884), p. 533.

- John Nichols, Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities, of King James the First, vol. 2 (London, 1828), pp. 46-7: Francis Palgrave, Ancient Kalendars and Inventories of the Treasury of the Exchequer, vol. 2 (London, 1836), p. 305: Joseph Robertson, Inventaires (Edinburgh, 1863), p. cxxxviii.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. 460, 478, 493.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 3, pp. 436, 438, 469, 563: Robertson (1863), p. clvii.

- Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 242–59.

- Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 254–274.

- Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 242.

- William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1586-1588, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1915), p. 228, Cecil Papers, vol. XX.

- A. Labanoff, Lettres Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 231-274.

- Labanoff, 7, p. 246.

- A necklace in the Royal Collection, associated with Mary Queen of Scots, from the collections of the Earls of Eglinton, RCIN 65620

- Necklace, National Museums of Scotland, IL.2001.50.34

- Kirsten Aschengreen & Joan Boardman, Ancient and Modern Gems and Jewels: In the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (London, 2008), p. 190.

- Diana Scarisbrick, 'Anne of Denmark's Jewellery Inventory', Archaeologia or Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Antiquity, 109, (Torquay, 1991), pp. 200, 212-3 no. 196, 226, the inventory is National Library of Scotland Adv. MS 31.1.10: Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts (Manchester, 2020), p. 140.

- John Kerr, The Golf-Book of East Lothian (Edinburgh, 1896), p. 247.

- William Fraser, Memorials of the Montgomeries, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1859), pp. 255-8.

- Una Pope-Hennessy, Agnes Strickland: Biographer of the Queens of England, 1796-1874 (London, 1940), pp. 209-10: Jane Margaret Strickland, Life of Agnes Strickland (Edinburgh, 1887), p. 169.

- John Kerr, The Golf-Book of East Lothian (Edinburgh, 1896), p. 247.

- George Seton, A history of the family of Seton during eight centuries, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1896), pp. 134-5

- A necklace in the Royal Collection, associated with Mary Queen of Scots, from the collections of the Earls of Eglinton, RCIN 65620

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 142.

- James Aikman, History of Scotland of George Buchanan, vol. 2 (Glasgow, 1827), pp. 497-8: John Hosack, Mary Queen of Scots and her accusers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1870), p. 542: Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1563-1603, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 558, the original has "palmall and goif"

- George Seton, A history of the family of Seton during eight centuries, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1896), p. 133 fn. 3: Monsignor Seton, Golf Illustrated, 10 (Nov. 1901).

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1914), p. 330.

- Rosalind K. Marshall, Mary, Queen of Scots: "In my end is my beginning" (Edinburgh, 2013), p. 83.

- Necklace, locket & pendant, known as Penicuik Jewels, associated with Mary, Queen of Scots, NMS H.NA 421

- Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 259, 265, 269, 272.

- Siobhan Talbott, 'Letter-Book of John Clerk of Penicuik', Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, XV, (Woodbridge, 2014), p. 11.

- Walter Seton, The Penicuik jewels of Mary Queen of Scots (Edinburgh, 1923), p. 29

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-1574, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), pp. 603-4.

- John Graham Dalyell, 'Diarey of Robert Birrel', p. 57: Robert Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland, 2:2 (Edinburgh, 1833), p. 408.

- Thomas Thomson, A Collection of Royal Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815)

- Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse Douairiere de France: Catalogues of the Jewels, Dresses, Furniture, of Mary of Queen of Scots (Edinburgh, 1863)

- Andrew Lang, Portraits and jewels of Mary Stuart, (Glasgow, 1906)

- Jane Kingsley-Smith, Cupid in Early Modern Literature and Culture (Cambridge, 2010), p. 97.

- Thomson (1815), p. 70.

- Felicity Heal, 'Royal Gifts and Gift Exchange in Anglo-Scottish Politics', in Steve Boardman, Julian Goodare, Kings, Lords and Men in Scotland and Britain 1300–1625, Essays in Honour of Jenny Wormald (Edinburgh, 2014), p. 289.

- HMC 11th Report, Part VI: Duke of Hamilton (London, 1887), pp. 41–2

- Thomson (1815), pp. 117-20.

- CSP Scotland, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 604.

- Robertson (1863), pp. clii-cliv.

- William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-4, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 584.

- Robertson (1863), pp. cl-cli.

- HMC Salisbury Hatfield, vol. 2 (London, 1888), pp. 56-7

- Robertson (1863), pp. clv-clviii.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1574–1581, vol. 5 (London, 1907), pp. 615-623.

- Edinburgh Castle Research: The Dolls of Mary Queen of Scots (Historic Environment Scotland, 2019)

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1574–1581, vol. 5 (London, 1907), p. 283, the copy in the National Archives of Scotland was printed in Thomson (1815), pp. 203–261.

- Printed, Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London, 1852), pp. 254–274: Noted, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 9 (London, 1915), p. 304.

External links

- Royal Collection: The Seton Parure: Poet Liz Lochlead examines the jewel

- Objects associated with Mary, Queen of Scots: National Museums of Scotland

- The Galloway Mazer, a cup made for Helen Acheson and Archibald Stewart, NMS

- Wardrobe of a Renaissance Queen: Mary’s Clothing Inventories

- Documents from the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, National Records of Scotland

- From the NRS Archives: Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587)

- Mary, Queen of Scots in 10 Objects, National Galleries of Scotland

- Will of Agnes Mowbray (d. 1575), sister of Geillis Mowbray, National Records of Scotland