Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (/ˈɡuːtənbɜːrɡ/;[1] c. 1400[2] – February 3, 1468) was a German goldsmith, inventor, printer, and publisher who introduced printing to Europe with his mechanical movable-type printing press. His work started the Printing Revolution and is regarded as a milestone of the second millennium, ushering in the modern period of human history.[3] It played a key role in the development of the Renaissance, Reformation, Age of Enlightenment, and Scientific Revolution, as well as laying the material basis for the modern knowledge-based economy and the spread of learning to the masses.[4]

Johannes Gutenberg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg c. 1400 |

| Died | February 3, 1468 (aged about 68) |

| Occupation | Engraver, inventor, and printer |

| Known for | The invention of the movable-type printing press |

Gutenberg in 1439 was the first European to use movable type. Among his many contributions to printing are: the invention of a process for mass-producing movable type; the use of oil-based ink for printing books;[5] adjustable molds;[6] mechanical movable type; and the use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of the period.[7] His truly epochal invention was the combination of these elements into a practical system that allowed the mass production of printed books and was economically viable for printers and readers alike. Gutenberg's method for making type is traditionally considered to have included a type metal alloy and a hand mould for casting type. The alloy was a mixture of lead, tin, and antimony that melted at a relatively low temperature for faster and more economical casting, cast well, and created a durable type.

In Renaissance Europe, the arrival of mechanical movable type printing introduced the era of mass communication which permanently altered the structure of society. The relatively unrestricted circulation of information—including revolutionary ideas—transcended borders, captured the masses in the Reformation and threatened the power of political and religious authorities; the sharp increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the literate elite on education and learning and bolstered the emerging middle class. Across Europe, the increasing cultural self-awareness of its people led to the rise of proto-nationalism, accelerated by the flowering of the European vernacular languages to the detriment of Latin's status as lingua franca. In the 19th century, the replacement of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press by steam-powered rotary presses allowed printing on an industrial scale, while Western-style printing was adopted all over the world, becoming practically the sole medium for modern bulk printing.

The use of movable type was a marked improvement on the handwritten manuscript, which was the existing method of book production in Europe, and upon woodblock printing, and revolutionized European book-making. Gutenberg's printing technology spread rapidly throughout Europe and later the world. His major work, the Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible), was the first printed version of the Bible and has been acclaimed for its high aesthetic and technical quality.

Early life

Gutenberg was born in the German city of Mainz, Rhine-Main area, the youngest son of the patrician merchant Friele Gensfleisch zur Laden, and his second wife, Else Wyrich, who was the daughter of a shopkeeper. It is assumed that he was baptized in the area close to his birthplace of St. Christoph.[8] According to some accounts, Friele was a goldsmith for the bishop at Mainz, but most likely, he was involved in the cloth trade.[9] Gutenberg's year of birth is not precisely known, but it was sometime between the years of 1394 and 1404. In the 1890s the city of Mainz declared his official and symbolic date of birth to be June 24, 1400.[10]

John Lienhard, technology historian, says "Most of Gutenberg's early life is a mystery. His father worked with the ecclesiastic mint. Gutenberg grew up knowing the trade of goldsmithing."[11] This is supported by historian Heinrich Wallau, who adds, "In the 14th and 15th centuries his [ancestors] claimed a hereditary position as ... retainers of the household of the master of the archiepiscopal mint. In this capacity they doubtless acquired considerable knowledge and technical skill in metal working. They supplied the mint with the metal to be coined, changed the various species of coins, and had a seat at the assizes in forgery cases."[12]

Wallau adds, "His surname was derived from the house inhabited by his father and his paternal ancestors 'zu Laden, zu Gutenberg'. The house of Gänsfleisch was one of the patrician families of the town, tracing its lineage back to the thirteenth century."[12] Patricians (the wealthy and political elite) in Mainz were often named after houses they owned. Around 1427, the name zu Gutenberg, after the family house in Mainz, is documented to have been used for the first time.[9]

In 1411, there was an uprising in Mainz against the patricians, and more than a hundred families were forced to leave. As a result, the Gutenbergs are thought to have moved to Eltville am Rhein (Alta Villa), where his mother had an inherited estate. According to historian Heinrich Wallau, "All that is known of his youth is that he was not in Mainz in 1430. It is presumed that he migrated for political reasons to Strasbourg, where the family probably had connections."[12] He is assumed to have studied at the University of Erfurt, where there is a record of the enrolment of a student called Johannes de Altavilla in 1418—Altavilla is the Latin form of Eltville am Rhein.[13][14]

Nothing is now known of Gutenberg's life for the next fifteen years, but in March 1434, a letter by him indicates that he was living in Strasbourg, where he had some relatives on his mother's side. He also appears to have been a goldsmith member enrolled in the Strasbourg militia. In 1437, there is evidence that he was instructing a wealthy tradesman on polishing gems, but where he had acquired this knowledge is unknown. In 1436/37 his name also comes up in court in connection with a broken promise of marriage to a woman from Strasbourg, Ennelin.[15] Whether the marriage actually took place is not recorded. Following his father's death in 1419, he is mentioned in the inheritance proceedings.

Printing press

Around 1439, Gutenberg was involved in a financial misadventure making polished metal mirrors (which were believed to capture holy light from religious relics) for sale to pilgrims to Aachen: in 1439 the city was planning to exhibit its collection of relics from Emperor Charlemagne but the event was delayed by one year due to a severe flood and the capital already spent could not be repaid.

Until at least 1444 Gutenberg lived in Strasbourg, most likely in the St. Arbogast parish. It was in Strasbourg in 1440 that he is said to have perfected and unveiled the secret of printing based on his research, mysteriously entitled Aventur und Kunst (enterprise and art). It is not clear what work he was engaged in, or whether some early trials with printing from movable type may have been conducted there. After this, there is a gap of four years in the record. In 1448, he was back in Mainz, where he took out a loan from his brother-in-law Arnold Gelthus, quite possibly for a printing press or related paraphernalia. By this date, Gutenberg may have been familiar with intaglio printing; it is claimed that he had worked on copper engravings with an artist known as the Master of Playing Cards.[17]

Future pope Pius II in a letter to Cardinal Carvajal, March 1455[10]

By 1450, the press was in operation, and a German poem had been printed, possibly the first item to be printed there.[18] Gutenberg was able to convince the wealthy moneylender Johann Fust for a loan of 800 guilders. Peter Schöffer, who became Fust's son-in-law, also joined the enterprise. Schöffer had worked as a scribe in Paris and is believed to have designed some of the first typefaces.

Gutenberg's workshop was set up at Hof Humbrecht, a property belonging to a distant relative. It is not clear when Gutenberg conceived the Bible project, but for this he borrowed another 800 guilders from Fust, and work commenced in 1452. At the same time, the press was also printing other, more lucrative texts (possibly Latin grammars). There is also some speculation that there may have been two presses, one for the pedestrian texts, and one for the Bible. One of the profit-making enterprises of the new press was the printing of thousands of indulgences for the church, documented from 1454 to 1455.[19]

In 1455 Gutenberg completed his 42-line Bible, known as the Gutenberg Bible. About 180 copies were printed, most on paper and some on vellum.

Court case

Some time in 1456, there was a dispute between Gutenberg and Fust, and Fust demanded his money back, accusing Gutenberg of misusing the funds. Gutenberg's two rounds of financing from Fust, a total of 1,600 guilders at 6% interest, now amounted to 2,026 guilders.[20] Fust sued at the archbishop's court. A November 1455 legal document records that there was a partnership for a "project of the books," the funds for which Gutenberg had used for other purposes, according to Fust. The court decided in favor of Fust, giving him control over the Bible printing workshop and half of all printed Bibles.

Thus Gutenberg was effectively bankrupt, but it appears he retained (or restarted) a small printing shop, and participated in the printing of a Bible in the town of Bamberg around 1459, for which he seems at least to have supplied the type. But since his printed books never carry his name or a date, it is difficult to be certain, and there is consequently a considerable scholarly debate on this subject. It is also possible that the large Catholicon dictionary, 300 copies of 754 pages, printed in Mainz in 1460, was executed in his workshop.

Meanwhile, the Fust–Schöffer shop was the first in Europe to bring out a book with the printer's name and date, the Mainz Psalter of August 1457, and while proudly proclaiming the mechanical process by which it had been produced, it made no mention of Gutenberg.

Later life

In 1462, during the devastating Mainz Diocesan Feud, Mainz was sacked by archbishop Adolph von Nassau, and Gutenberg was exiled. An old man by now, he moved to Eltville where he may have initiated and supervised a new printing press belonging to the brothers Bechtermünze.[12]

In January 1465, Gutenberg's achievements were recognized and he was given the title Hofmann (gentleman of the court) by von Nassau. This honor included a stipend, an annual court outfit, as well as 2,180 litres of grain and 2,000 litres of wine tax-free.[21] It is believed he may have moved back to Mainz around this time, but this is not certain.

Gutenberg died in 1468 and was buried in the Franciscan church at Mainz, his contributions largely unknown. This church and the cemetery were later destroyed, and Gutenberg's grave is now lost.[21]

In 1504, he was mentioned as the inventor of typography in a book by Professor Ivo Wittig. It was not until 1567 that the first portrait of Gutenberg, almost certainly an imaginary reconstruction, appeared in Heinrich Pantaleon's biography of famous Germans.[21]

Printed books

Between 1450 and 1455, Gutenberg printed several texts, some of which remain unidentified; his texts did not bear the printer's name or date, so attribution is possible only from typographical evidence and external references. Certainly several church documents including a papal letter and two indulgences were printed, one of which was issued in Mainz. In view of the value of printing in quantity, seven editions in two styles were ordered, resulting in several thousand copies being printed.[22] Some printed editions of Ars Minor, a schoolbook on Latin grammar by Aelius Donatus may have been printed by Gutenberg; these have been dated either 1451–52 or 1455.

In 1455, Gutenberg completed copies of a beautifully executed folio Bible (Biblia Sacra), with 42 lines on each page. Copies sold for 30 florins each,[23] which was roughly three years' wages for an average clerk. Nonetheless, it was significantly cheaper than a manuscript Bible that could take a single scribe over a year to prepare. After printing, some copies were rubricated or hand-illuminated in the same elegant way as manuscript Bibles from the same period.

48 substantially complete copies are known to survive, including two at the British Library that can be viewed and compared online.[24] The text lacks modern features such as page numbers, indentations, and paragraph breaks.

An undated 36-line edition of the Bible was printed, probably in Bamberg in 1458–60, possibly by Gutenberg. A large part of it was shown to have been set from a copy of Gutenberg's Bible, thus disproving earlier speculation that it was the earlier of the two.[25]

Printing method with movable type

Gutenberg's early printing process, and what texts he printed with movable type, are not known in great detail. His later Bibles were printed in such a way as to have required large quantities of type, some estimates suggesting as many as 100,000 individual sorts.[28] Setting each page would take, perhaps, half a day, and considering all the work in loading the press, inking the type, pulling the impressions, hanging up the sheets, distributing the type, etc., it is thought that the Gutenberg–Fust shop might have employed as many as 25 craftsmen.

Gutenberg's technique of making movable type remains unclear. In the following decades, punches and copper matrices became standardized in the rapidly disseminating printing presses across Europe. Whether Gutenberg used this sophisticated technique or a somewhat primitive version has been the subject of considerable debate.

In the standard process of making type, a hard metal punch (made by punchcutting, with the letter carved back to front) is hammered into a softer copper bar, creating a matrix. This is then placed into a hand-held mould and a piece of type, or "sort", is cast by filling the mould with molten type-metal; this cools almost at once, and the resulting piece of type can be removed from the mould. The matrix can be reused to create hundreds, or thousands, of identical sorts so that the same character appearing anywhere within the book will appear very uniform, giving rise, over time, to the development of distinct styles of typefaces or fonts. After casting, the sorts are arranged into type cases, and used to make up pages which are inked and printed, a procedure which can be repeated hundreds, or thousands, of times. The sorts can be reused in any combination, earning the process the name of "movable type". (For details, see Typography.)

The invention of the making of types with punch, matrix and mold has been widely attributed to Gutenberg. However, recent evidence suggests that Gutenberg's process was somewhat different. If he used the punch and matrix approach, all his letters should have been nearly identical, with some variation due to miscasting and inking. However, the type used in Gutenberg's earliest work shows other variations.

In 2001, the physicist Blaise Agüera y Arcas and Princeton librarian Paul Needham, used digital scans of a Papal bull in the Scheide Library, Princeton, to carefully compare the same letters (types) appearing in different parts of the printed text.[29][30] The irregularities in Gutenberg's type, particularly in simple characters such as the hyphen, suggested that the variations could not have come either from ink smear or from wear and damage on the pieces of metal on the types themselves. Although some identical types are clearly used on other pages, other variations, subjected to detailed image analysis, suggested that they could not have been produced from the same matrix. Transmitted light pictures of the page also appeared to reveal substructures in the type that could not arise from traditional punchcutting techniques. They hypothesized that the method involved impressing simple shapes to create alphabets in "cuneiform" style in a matrix made of some soft material, perhaps sand. Casting the type would destroy the mould, and the matrix would need to be recreated to make each additional sort. This could explain the variations in the type, as well as the substructures observed in the printed images.

Thus, they speculated that "the decisive factor for the birth of typography", the use of reusable moulds for casting type, was a more progressive process than was previously thought.[31] They suggested that the additional step of using the punch to create a mould that could be reused many times was not taken until twenty years later, in the 1470s. Others have not accepted some or all of their suggestions, and have interpreted the evidence in other ways, and the truth of the matter remains uncertain.[32]

.tiff.jpg.webp)

A 1568 book Batavia by Hadrianus Junius from Holland claims that the idea of the movable type came to Gutenberg from Laurens Janszoon Coster via Fust, who was apprenticed to Coster in the 1430s and may have brought some of his equipment from Haarlem to Mainz. While Coster appears to have experimented with moulds and castable metal type, there is no evidence that he had actually printed anything with this technology. He was an inventor and a goldsmith. However, there is one indirect supporter of the claim that Coster might be the inventor. The author of the Cologne Chronicle of 1499 quotes Ulrich Zell, the first printer of Cologne, that printing was performed in Mainz in 1450, but that some type of printing of lower quality had previously occurred in the Netherlands. However, the chronicle does not mention the name of Coster,[25][33] while it actually credits Gutenberg as the "first inventor of printing" in the very same passage (fol. 312). The first securely dated book by Dutch printers is from 1471,[33] and the Coster connection is today regarded as a mere legend.[34]

The 19th-century printer and typefounder Fournier Le Jeune suggested that Gutenberg was not using type cast with a reusable matrix, but wooden types that were carved individually. A similar suggestion was made by Nash in 2004.[35] This remains possible, albeit entirely unproven.

Legacy

American writer Mark Twain (1835−1910)[36]

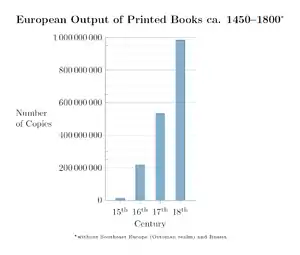

Although Gutenberg was financially unsuccessful in his lifetime, the printing technologies spread quickly, and news and books began to travel across Europe much faster than before. It fed the growing Renaissance, and since it greatly facilitated scientific publishing, it was a major catalyst for the later scientific revolution.

The capital of printing in Europe shifted to Venice, where visionary printers like Aldus Manutius ensured widespread availability of the major Greek and Latin texts. The claims of an Italian origin for movable type have also focused on this rapid rise of Italy in movable-type printing. This may perhaps be explained by the prior eminence of Italy in the paper and printing trade. Additionally, Italy's economy was growing rapidly at the time, facilitating the spread of literacy. Christopher Columbus had a geography book (printed with movable type) bought by his father. That book is in a Spanish museum, the Biblioteca Colombina in Seville. Finally, the city of Mainz was sacked in 1462, driving many (including a number of printers and punch cutters) into exile.

Printing was also a factor in the Reformation. Martin Luther's Ninety-five Theses were printed and circulated widely; subsequently he issued broadsheets outlining his anti-indulgences position (certificates of indulgences were one of the first items Gutenberg had printed). The broadsheet contributed to development of the newspaper.

In the decades after Gutenberg, many conservative patrons looked down on cheap printed books; books produced by hand were considered more desirable.

Today there is a large antique market for the earliest printed objects. Books printed prior to 1500 are known as incunabula.

There are many statues of Gutenberg in Germany, including the famous one by Bertel Thorvaldsen (1837) at Gutenbergplatz in Mainz, home to the eponymous Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz and the Gutenberg Museum on the history of early printing. The latter publishes the Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, the leading periodical in the field.

Project Gutenberg, the oldest digital library,[37] commemorates Gutenberg's name. The Mainzer Johannisnacht commemorates the person Johannes Gutenberg in his native city since 1968.

In 1952, the United States Postal Service issued a five hundredth anniversary stamp commemorating Johannes Gutenberg invention of the movable-type printing press.

In 1961 the Canadian philosopher and scholar Marshall McLuhan entitled his pioneering study in the fields of print culture, cultural studies, and media ecology, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man.

Regarded as one of the most influential people in human history, Gutenberg remains a towering figure in the popular image. In a 1978 book by a historian that purports to rank the 100 most influential persons in history, Gutenberg comes in at number 8, after T'sai Lun and before Christopher Columbus.[38] In 1999, the A&E Network ranked Gutenberg the No. 1 most influential person of the second millennium on their "Biographies of the Millennium" countdown. In 1997, Time–Life magazine picked Gutenberg's invention as the most important of the second millennium.[3]

In space, he is commemorated in the name of the asteroid 777 Gutemberga.

Two operas based on Gutenberg are G, Being the Confession and Last Testament of Johannes Gensfleisch, also known as Gutenberg, Master Printer, formerly of Strasbourg and Mainz, from 2001 with music by Gavin Bryars;[39] and La Nuit de Gutenberg, with music by Philippe Manoury, premiered in 2011 in Strasbourg.[40]

In 2018, WordPress, the open-source CMS platform, named its new editing system Gutenberg in tribute to him.[41]

See also

References

- Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: Gutenberg, Johann". www.ahdictionary.com.

- Childress 2008, p. 14

- See People of the Millenium Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine for an overview of the wide acclaim. In 1999, the A&E Network ranked Gutenberg no. 1 on their "People of the Millennium" countdown. In 1997, Time–Life magazine picked Gutenberg's invention as the most important of the second millennium Archived 2010-03-10 at the Wayback Machine; the same did four prominent US journalists in their 1998 resume 1,000 Years, 1,000 People: Ranking The Men and Women Who Shaped The Millennium . The Johann Gutenberg entry of the Catholic Encyclopedia describes his invention as having made a practically unparalleled cultural impact in the Christian era.

- McLuhan 1962; Eisenstein 1980; Febvre & Martin 1997; Man 2002

- Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising By Juliann Sivulka, page 5

- "Gutenberg's Invention - Fonts.com". Fonts.com.

- "How Gutenberg Changed the World". livescience.com.

- St. Christopher's – Gutenberg's baptismal church

- Hanebutt-Benz, Eva-Maria. "Gutenberg and Mainz". Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- Childress 2008, p. 62

- "Lienhard, John H". Uh.edu. 2004-08-01. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- Wallau, Heinrich. "Johann Gutenberg". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

- Martin, Henri-Jean (1995). "The arrival of print". The History and Power of Writing. University of Chicago Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-226-50836-6.

- Dudley, Leonard (2008). "The Map-maker's son". Information revolutions in the history of the West. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-84720-790-6.

- "Gutenberg und seine Zeit in Daten (Gutenberg and his times; Timeline)". Gutenberg Museum. Archived from the original on 2006-12-22. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- Wolf 1974, pp. 67f.

- Lehmann-Haupt, Hellmut (1966). Gutenberg and the Master of the Playing Cards. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Klooster, John W. (2009). Icons of invention: the makers of the modern world from Gutenberg to Gates. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-313-34745-0.

- Kelley, Peter. "Documents that Changed the World: Gutenberg indulgence, 1454". UW Today. University of Washington. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Sumner, Tracy M. (2009). How Did We Get the Bible? (unabridged ed.). Barbour Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60742-349-2.

- Meggs, Philip B.; Purvis, Alston W. (2016). Meggs' History of Graphic Design. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 435–36, 442–43. ISBN 978-1-119-13623-1.

- Cormack, Lesley B.; Ede, Andrew (2004). A History of Science in Society: From Philosophy to Utility. Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-332-5.

- "Treasures in Full: Gutenberg Bible". British Library. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- Kapr, Albert (1996). Johannes Gutenberg: the Man and His Invention. Scolar Press. p. 322. ISBN 1-85928-114-1.

- Duchesne 2006, p. 83

- Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: "Charting the "Rise of the West": Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), pp. 409–4 45 (417, table 2)

- Singer, C.; Holmyard, E.; Hall, A.; Williams, T. (1958). A History of Technology, vol. 3. Oxford University Press.

- Agüera y Arcas, Blaise; Needham, Paul (November 2002). "Computational analytical bibliography". Proceedings Bibliopolis Conference The future history of the book. The Hague (Netherlands): Koninklijke Bibliotheek.

- "What Did Gutenberg Invent?". Retrieved Aug 16, 2011.

- Adams, James L. (1991). Flying Buttresses, Entropy and O-Rings: the World of an Engineer. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-30688-0.

- Nash, Paul W. "The 'first' type of Gutenberg: a note on recent research" in The Private Library, Summer 2004, pp. 86–96.

- Juchhoff 1950, pp. 131f.

- Costeriana. While the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition had attributed the invention of the printing press to Coster, the more recent editions of the work attribute it to Gutenberg to reflect, as it says, the common consent that has developed in the 20th century. "Typography – Gutenberg and printing in Germany." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- See Nash (2004).

- Childress 2008, p. 122

- Thomas, Jeffrey (20 June 2007). "Project Gutenberg Digital Library Seeks To Spur Literacy". U.S. Department of State, Bureau of International Information Programs. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- Hart, Michael H. (1978). The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History, pp. 66, 72, & 78. A & W Publishers.

- Gavin Bryars (2011-04-18). "Gavin Bryars Introduces". WQXR. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- "UC San Diego Composer Philippe Manoury Wins French Grammy" (Press release). University of California San Diego News Center. 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- "The new Gutenberg editing experience". wordpress.org.

Sources

- Childress, Diana (2008). Johannes Gutenberg and the Printing Press. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-7613-4024-9.

- Duchesne, Ricardo (2006). "Asia First?". The Journal of the Historical Society. 6 (1): 69–91. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2006.00168.x.

- Juchhoff, Rudolf (1950). "Was bleibt von den holländischen Ansprüchen auf die Erfindung der Typographie?". Gutenberg-Jahrbuch: 128–133.

- Wolf, Hans-Jürgen (1974). "Geschichte der Druckpressen" (1st ed.). Frankfurt/Main: Interprint. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Blake Morrison, The Justification of Johann Gutenberg (2000) [Novel, describing social and technical aspects of the invention of printing]

- Albert Kapr, Johann Gutenberg: the Man and his Invention. Translated from the German by Douglas Martin, Scolar Press, 1996. "Third ed., revised by the author for...the English translation".

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth (1980). The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29955-1.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth (2005). The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe (2nd, rev. ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-60774-4. [More recent, abridged version]

- Febvre, Lucien; Martin, Henri-Jean (1997). The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-108-2.

- Man, John (2002). The Gutenberg Revolution: The Story of a Genius and an Invention that Changed the World. London: Headline Review. ISBN 978-0-7472-4504-9.

- McLuhan, Marshall (1962). The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1st ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6041-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johannes Gutenberg. |

- English homepage of the Gutenberg-Museum Mainz, Germany.

- The Digital Gutenberg Project: the Gutenberg Bible in 1,300 digital images, every page of the University of Texas at Austin copy.

- Treasures in Full – Gutenberg Bible View the British Library's Digital Versions Online

- Giovanni Balbi. Catholicon. Mainz: Printed by Johann Gutenberg? 1460, at The Library of Congress.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Gutenberg, Johannes". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Gutenburg, Johannes". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Gutenberg, Johann". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Johann Gutenberg". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- "Gutenberg, Johannes". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Gutenberg, Johannes". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Gutenberg, Johannes". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.