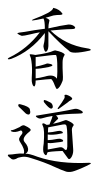

Kōdō

Kōdō (香道, "Way of Fragrance") is the art of appreciating Japanese incense, and involves using incense within a structure of codified conduct. Kōdō includes all aspects of the incense process, from the tools (香道具, kōdōgu), to activities such the incense-comparing games kumikō (組香) and genjikō (源氏香).[1] Kōdō is counted as one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement, along with kadō for flower arrangement, and chadō for tea and the tea ceremony.[2]

.JPG.webp)

Etymology

The word 香 kō is written with the Chinese Kangxi radical 186 composed of nine strokes, which can also be expanded up to 18 strokes 馫. Translated it means "fragrance"; however in this context may also be translated as "incense".

The word 道 dō (written with the same character as Chinese tao/dao) means "way", both literally (street) and metaphorically (a stream of life experience). The suffix -道 generally denotes, in the broadest sense, the totality of a movement as endeavor, tradition, practice and ethos.

In the search for a suitable term, translations of such words into English sometimes focus on a narrower aspect of the original term. One common translation in context is "ceremony", which entails the process of preparation and smelling in general, but not a specific instance. In some instances, it functions similarly to the English suffix -ism, and as in the case of tea (chadō/sadō 茶道) one sees teaism in works dating from early efforts at illustrating sadō in English, focusing on its philosophy and ethos.

Conversely, the sense of the English phrase the way of X appears to have broadened in response to the need to translate such terms, and to have become more productive with the need to describe with a similar breadth of compass certain things in Western experience.

History

_with_Peonies_-_Walters_491755.jpg.webp)

According to legend, agarwood (aloeswood) first came to Japan when a log of incense wood drifted ashore on Awaji island in the third year of Empress Suiko's reign (595 CE). People who found the incense wood noticed that the wood smelled marvelous when they put it near a fire. Then they presented the wood to local officials.

Japan was the eastern end of the Silk Road. Incense was brought from China over Korea and developed over 1000 years. The history starts in the 6th century CE when Buddhism arrived during the Asuka period. Agarwood is known to have come along with the supplies to build a temple in 538 CE. A ritual known as sonaekō became established. Kōboku, fragrant wood combined with herbs and other aromatic substances, was burned to provide incense for religious purposes.[3] The custom of burning incense was further developed and blossomed amongst the court nobility.[4] Pastime of takimono, a powdered mixture of aromatic substances, developed.[5] Fragrant scents played a vital role at court life during the Heian period, robes and even fans were perfumed and poems written about them, it also featured prominently in the epic The Tale of Genji in the 11th century.

Samurai warriors would prepare for battle by purifying their minds and bodies with the incense of kōboku. They also developed an appreciation for its fragrances. In the late Muromachi period in the 16th century, this aesthetic awareness would develop into the accomplishment known as kōdō, which is the art of enjoying the incense of smouldering kōboku. The present style of kōdō has largely retained the structure and manner of the Muromachi period, during this time the tea ceremony and the ikebana style of flower arrangement developed as well.

Expertise concerning tiny pieces of exotic aromatic woods led in the 15th and 16th centuries to the creation of various games or contests. Some depended on the memorization of scents, some involved sequences that held clues to classic poems, some merely a matter of identifying matching aromas. Incense games became a "way" (dō), an avocation. The way of incense eventually spread from elite circles to townsmen.

During the Tenshō era in the late 16th century, the master craftsmen Kōju was employed at the Kyoto Imperial Palace and practiced incense ceremony. The third Kōju served under Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the fourth under Tokugawa Ieyasu. The eighth Kōju Takae Jyuemon was known as a particular master of incense of note.

During this time the “Ten Virtues of Kō” (香の十徳, kōnojūtoku) were formulated, which is a traditional listing of the benefits derived from the proper and correct use of quality incense:[6][7][8]

- 感格鬼神 : Sharpens the senses

- 清浄心身 : Purifies the body and the spirit

- 能払汚穢 : Eliminates pollutants

- 能覚睡眠 : Awakens the spirit

- 静中成友 : Heals loneliness

- 塵裏愉閑 : Calms in turbulent times

- 多而不厭 : Is not unpleasant, even in abundance

- 募而知足 : Even in small amounts is sufficient

- 久蔵不朽 : Does not break down after a very long time

- 常用無障 : A common use is not harmful

Even today, there is a strong relationship and holistic approach in kōdō between fragrant scent, the senses, the human spirit, and nature. The spirituality and refined concentration that is central to kōdō places it on the same level as kadō and chadō.

Material

In kōdō, a small piece of fragrant wood is heated on a small Mica plate (Gin-yo), which is heated from below by a piece of charcoal that is surrounded by ash. All this is held in a small ceramic censer that can look like a cup. It is not usual for wood or incense sticks to be burned because that would create smoke; only the essential aromatic oils should be released from the wood through the heat below it.

Aloeswood, also known as agarwood (沈香 jinkō), is produced in certain parts of southeast Asia such as Vietnam. The trees secrete an aromatic resin, which over time then turns into kōboku (香木). One particular grade of kōboku with a high oil content and superior fragrance is called kyara (伽羅).

Another important material is sandalwood (白檀 byakudan), which originates primarily from India, Indonesia, southern China or other parts of southeast Asia. Sandalwood trees need around 60 years to produce their signature fragrance that can be deemed acceptable to be used for kōdo.

Other materials used are cinnamon bark (桂皮 keihi), chebulic myrobalan (诃子 kashi), clove (丁子 choji), ginger lily (sanna), lavender, licorice (甘草属 kanzō), patchouli (廣藿香 kakkō), spikenard (匙葉甘鬆 kansho), camomile, rhubarb (大黄 daioh), safflower (紅花 benibana), star anise (大茴香 dai uikyo) and other herbs. Shell fragrances (貝香 kaikō) and other animal-derived aromatic materials are also used.

Raw materials such as agarwood are becoming increasingly rare due to the depletion of the wild resource. This has made prime material very expensive. For example, the cost of lower grade kyara is about 20,000 yen per gram. Top quality kyara costs over 40,000 yen per gram, or many times the equivalent weight of gold (as of late 2012). Though it can only be warmed and used once for a formal ceremony, it can be stored for hundreds of years.

If the particular piece of incense wood has a history, the price can be even higher. The highest regarded wood, Ranjyatai (蘭奢待), dates back to at least the 10th century and is kyara wood from Laos or Vietnam, and was used by emperors and warlords for its fragrance. It is said to contain so much resin that it can be used many times over. The wood is kept at the Shōsōin treasury in Nara, which is under the administration of the Imperial Household.

The high costs and difficulty in obtaining acceptable raw material is one of the reasons why kōdō is not as widely practiced or known compared to the art of flower arrangement or the tea ceremony.

One of the oldest traditional incense companies in Japan is Baieido, founded in 1657 with roots going back to the Muromachi period. Other traditional and still operating companies include Kyukyodo (1663, Kyoto) and Shoyeido, founded in 1705. Nippon Kodo is also a major supplier of incense material.

Types of incense

Sasaki Dōyō (1306–1373), who was regarded as a paragon of elegance and luxury and the quintessential military aristocrat during Nanboku-chō period, owned many incense woods and named them.

Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–1490) himself appreciated precious scented woods and collected some or inherited them from Sasaki. In order to properly organise the large collection of incense wood, he appointed the experts of that time Sanjonishi Sanetaka, who became the founder of the Oie School, and Shino Soshin, the founder of the Shino School. They established a classifying system called rikkoku gomi, which means "six countries, five scents".

| Name | Character | rikkoku (country) | gomi (scent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| kyara | 伽羅 | Vietnam | bitter |

| rakoku | 羅国 | Thailand | sweet |

| manaka | 真那伽 | Malacca, Malaysia | no scent |

| manaban* | 真南蛮 | unknown | salty |

| sasora | 佐曽羅 | India | hot |

| sumotara / sumontara | 寸聞多羅 | Sumatra | sour |

* Manaban comes from the word nanban which means "southern barbarian", and was brought to Japan by Portuguese traders with unknown origin.[9]

Incense utensils

.JPG.webp)

Honkōban (本香盤), takigara-ire (炷空入), hidōgu (火道具).

Lower left to right: shinoori (志野折), two kōro (香炉), ginyō-bako (銀葉箱)

Incense utensils or equipment is called kōdōgu (香道具). A range of kōdōgu are available and different styles and motifs are used for different events and in different seasons. All the tools for incense ceremony are handled with exquisite care. They are scrupulously cleaned before and after each use and before storing. Much like the objects and tools used in the tea ceremony, these can be valued as high art.

The following are a few of the essential components:

- three-tiered container (jukōbako 重香箱), for the incense, new mica plates, and burned out incense with its used mica plate

- long tray (nagabon 長盆)

- censer (kōrō 香炉), also known as te-kōro (手香炉 "hand-held censer")

- Mica plates (gin-yo 銀葉), where the incense wood is placed to stop it from burning if it were to be placed directly on the ash

- Incense holder board (honkōban 本香盤), a small, wooden tablet with a flower-shaped mother-of-pearl fittings upon which the small incense pieces on mica plates are kept on top for display after use, normally 6 or 10 in number

- white ash (Trapa. Japonica), but also red ash or other precious ash can be used

- Shino incense packet (shinoori 志野折), folded paper packet used to keep incense wood chips (themselves in their individual packets), used by the Shino School

- box (ginyō-bako 銀葉箱), silver box for containing the mica plates

- charcoal (tadon 炭團), a special, and nearly odourless, charcoal briquette

A small vase (kōji-tate 香筯建), also known as koji-tate (火箸立), keeps the fire utensils (hidōgu 火道具):

- metal tweezers or tongs (ginyo-basami 銀葉挾) for handling the square mica plates

- ebony chopsticks (香筯), for picking up pieces of incense wood

- small spatula (香匙), for transferring incense wood onto the mica plate

- metal chopsticks (koji 火箸), used to move the charcoal

- tamper (ha i-oshi 灰押), an object shaped rather like a closed folding-fan, used to gently tamp and smooth the ashes in the censer into a cone around the burning charcoal

- feather brush (ko-hane 小羽), to clean and brush off any ashes

- answer sheet holder (鶯), for securing the sheet of paper with answers onto the tatami mat

Some other items can be included:

- small incense container (kōgō 香合), for keeping incense in, mainly as part of the tea ceremony, or in general

- ash container (takigara-ire 炷空入), where fresh ash is kept

Most of the utensils could be kept in a special cabinet (dogu-dana). Influential families would order elaborate and expensive cabinets made out precious woods and lacquer and goldwork.

Monkō

The art of enjoying incense, with all its preparatory aspects, is called monkō (聞香), which translated means "listening to incense" (although the 聞 Kanji also means "to smell" in Chinese). The aim is to let the aroma of the material infuse the body and soul and "listen" to its essence in a holistic manner, as opposed to just reducing it to smelling.[10] Monkō has been depicted in Japanese art, with a well-known depiction by the artist Shinsui Itō (1898–1972).[11]

Participants sit near one another and take turns smelling incense from a censer as they pass it around the group. Participants comment on and make observations about the incense, and play games to guess the incense material. Genjikō is one such game, in which participants are to determine which of five prepared censers contain different scents, and which contain the same scent. Players' determinations (and the actual answers) are recorded using symbols in kō no zu(香の図).

The kō no zu for Genjikō is Genjikō no zu(源氏香の図). The geometric pattern of these are also used as mon (called as Genjikō-mon(源氏香紋)), for decoration in a number of other areas such as kimono, Japanese lacquerware and Japanese pottery.

References

- Oller, David (1992–2002). "Kodo". Baieido. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- "Kodo - The Way of Incense". Japan Zone. 1999–2016. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- Oller, David (1992–2002). "Buddhist Incense - Sonae Koh". Baieido. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- Hearn, Lafcadio (1899). "Incense (IV)". Ghostly Japan. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 30.

Incense-burning has been an amusement of the aristocracy ever since the thirteenth century.

- Dalby, Liza (2017). "incense". Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- "The Ten Virtues of Koh". Nippon Kodo. 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- "香の十徳" (in Japanese). Komori. 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- "The Ten Virtues of Koh". Reed's Handmade Incense. 2018. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- "Aloeswood". Baieido. 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- "Monko (Listening to Incense) Course". Yamada-Matsu. 2008. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- "聞香(もんこう)". Cultural Heritage Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

Further reading

External links

![]() Media related to Kōdō at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kōdō at Wikimedia Commons

- Avivson, Janus (Director) (2007). Kodo: The Art of Japanese Incense (Documentary). United Kingdom. Retrieved 2017-04-12.