Kimono

The kimono (きもの/着物) (lit., "thing to wear" – from the verb ki (着), "to wear (on the shoulders)" and the noun mono (物), "thing")[1] is a traditional Japanese garment and the national dress of Japan. The kimono is a T-shaped, wrapped-front garment with square sleeves and a rectangular body, and is worn left side wrapped over right, unless the wearer is deceased.[2] The kimono is traditionally worn with an obi, and is commonly worn with accessories such as zōri sandals and tabi socks.

.jpg.webp)

| Kimono | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Kimono" in kanji | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 着物 | ||||

| |||||

Kimono have a set method of construction and are typically made from a long, narrow bolt of cloth known as a tanmono, though Western-style fabric bolts are also sometimes used.[3] There are different types of kimono for men, women and children, varying based on the occasion, the season, the wearer's age, and - less commonly in the modern day - the wearer's marital status. Despite perception of the kimono as a formal and difficult to wear garment, there are types of kimono suitable for every formality, including informal occasions. The way a person wears their kimono is known as kitsuke (着付け) (lit., "dressing").

In the present day, the kimono is uncommonly worn as everyday dress, and has steadily fallen out of fashion as the most common garment for a Japanese person to own and wear. Kimono are now most frequently seen at summer festivals, where people frequently wear the yukata, the most informal type of kimono; however, the kimono is also worn to funerals, weddings and other formal events. The people who wear the kimono most frequently in Japanese society are older men and women - who may have grown up wearing it, though less commonly than in previous generations - geisha and maiko, who are required to wear it as part of their profession, and sumo wrestlers, who must wear kimono at all times in public.[4]

Despite the low numbers of people who wear kimono commonly and the garment's reputation as an uncomfortable piece of clothing, the kimono has experienced a number of revivals in previous decades, and is still worn today as fashionable clothing within Japan.

History

.jpg.webp)

The first instances of kimono-like garments in Japan were traditional Chinese clothing introduced to Japan via Chinese envoys in the Kofun period, with immigration between the two countries and envoys to the Tang dynasty court leading to Chinese styles of dress, appearance and culture becoming extremely popular in Japanese court society.[1] The Imperial Japanese court quickly adopted Chinese styles of dress and clothing,[7] with evidence of the oldest samples of shibori tie-dyed fabric stored at the Shosoin Temple being Chinese in origin, due to the limitations of Japan's ability to produce the fabrics stored there at the time.[8]

During the Heian period (794-1193 CE), Japan stopped sending envoys to the Chinese dynastic courts, leading to the prevention of Chinese-exported goods, including clothing, from entering the Imperial Palace, and thus disseminating to the upper classes, who were the main arbiters in the development of traditional Japanese culture at the time, and the only people able, or allowed, to wear such clothing. The ensuing cultural vacuum led to the facilitation of a Japanese culture independent from Chinese fashions to a much greater degree; this saw elements previously lifted from the Tang Dynastic courts develop independently into what is known literally as "national culture" or "kokufū culture" (国風文化, kokufū-bunka), the term used to refer to Heian-period Japanese culture, particularly that of the upper classes.[9]

Clothing became increasingly stylised, with some elements - such as the round-necked and tube-sleeved chun ju jacket, worn by both genders in the early 7th century - being abandoned by both male and female courtiers. Others, such as the wrapped front robes also worn by men and women, were kept, and some elements, such as the mo skirt worn by women, continued on in a reduced capacity, worn only to formal occasions.[1]

During the later Heian period, various clothing edicts reduced the number of layers a woman could wear, leading to the kosode - lit., "small sleeve" - garment, previously considered underwear, becoming outerwear by the time of the Muromachi period (1336-1573 CE). Originally worn with hakama trousers - another piece of underwear in the Heian period - the kosode began to be held closed with a small belt known as an obi.[1] The kosode resembled a modern kimono, though at this time, the sleeves were sewn shut at the back, and were smaller in width than the body of the garment. During the Sengoku period and the Azuchi-Momoyama period, decoration of the kosode developed further, with bolder designs and flashy primary colours becoming popular.

During the Edo period (1603-1867 CE), both Japan's culture and economy developed significantly, in particular during the Genroku period (1688-1704 CE), wherein "Genroku culture" - wherein luxurious displays of wealth were commonly displayed by the growing and powerful merchant classes (chōnin) - flourished. At this time, the clothing of chōnin classes, representative of their increasing economic power, rivalled that of the aristocracy and samurai classes, with their brightly coloured kimono utilising expensive production techniques, such as handpainted dyework. In response to this, the Tokugawa shogunate issued a number of sumptuary bans on the kimono of the merchant classes, prohibiting the use of purple or red fabric, gold embroidery, and the use of intricately dyed shibori patterns.[10]

As a result, a school of aesthetic thought known as "iki", which valued and prioritised the display of wealth through almost mundane appearances, developed, a concept of kimono design and wear that continues to this day as a major influence.

From this point onwards, the basic shape of both men's and women's kimono remained largely unchanged.[1] In the Edo period, the sleeves of the kosode began to grow in length, especially amongst unmarried women, and the obi became much longer and wider, with various styles of knots coming into fashion, alongside stiffer weaves of material to support them.[1]

During the Meiji era, the opening of Japan to Western trade after the enclosure of the Edo period led to a drive towards Western dress as a sign of "modernity". After an edict by Emperor Meiji, policemen, railroad workers and teachers moved to wearing Western clothing within their job roles, with the adoption of Western clothing by men in Japan happening at a much greater pace than by women. Initiatives such as the Tokyo Women's & Children's Wear Manufacturers' Association (東京婦人子供服組合) promoted Western dress as everyday clothing.

Western clothing quickly became standard issue as army uniform for men[11] and school uniform for boys, and between 1920 and 1930, the sailor outfit replaced the kimono and undivided hakama as school uniform for girls.[1]:140 However, kimono still remained popular as an item of everyday fashion; following the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, cheap, informal and ready-to-wear meisen kimono, woven from raw and waste silk threads unsuitable for other uses, became highly popular, following the loss of many people's possessions.[12] By 1930, ready-to-wear meisen kimono had become highly popular for their bright, seasonally changing designs, many of which took inspiration from the Art Deco movement. Meisen kimono were usually dyed using the ikat (kasuri) technique of dyeing, where either warp or both warp and weft threads (known as heiyō-gasuri)[12]:85 were dyed using a stencil pattern before weaving.

Today, the vast majority of people in Japan wear Western clothing in the everyday, and are most likely to wear kimono either to formal occasions such as wedding ceremonies and funerals, or to summer events, where the standard kimono is the easy-to-wear, single-layer cotton yukata. In the Western world, kimono-style women's jackets, similar to a casual cardigan,[13] gained public attention as a popular fashion item in 2014.[14]

In 2019, the mayor of Kyoto announced that his staff were working to register "Kimono Culture" on UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage list.[15]

Textiles

Both kimono and obi are made from a wide variety of fibre types, including hemp, linen, silk, crepe (known as chirimen), and figured satin weaves such as rinzu. Fabrics are typically – for both obi and kimono – woven as bolts of narrow width, save for certain types of obi (such as the maru obi) woven to double-width. Formal kimono are almost always made from silk, with thicker, heavier, stiff or matte fabrics generally being considered informal.

Following the opening of Japan's borders in the early Meiji period to Western trade, a number of materials and techniques - such as wool and the use of synthetic dyestuffs - became popular, with casual wool kimono being relatively common in pre-1960s Japan; the use of safflower dye ('beni') for silk linings fabrics (known as 'momi'; literally, "red silk") was also common in pre-1960s Japan, making kimono from this era easily identifiable. Fibres such as rayon became widespread during WW2, being inexpensive to produce and cheap to buy, and typically featured printed designs.

Modern kimono are widely available in fabrics considered easier to care for, such as polyester. Kimono linings are typically silk or imitation silk, and generally match the top fabric in fibre type, though the lining of some casual silk kimono may be cotton, wool or linen.

Terms

The fabrics that kimono are made from are classified in two categories within Japan. Gofuku (呉服) is the term used to indicate silk kimono fabrics, composed of the characters go (呉) (meaning "Wu" - a kingdom in ancient China where the technology of weaving silk developed) and fuku (服) (meaning "clothing").[16]:115[17]

The term 'gofuku' is also used to refer to kimono in general within Japan, particularly within the context of the kimono industry, as traditional kimono shops are referred to as either gofukuten (呉服店) or gofukuya (呉服屋) - with the additional character of "ya" (屋) meaning 'shop'.[18]

Cotton and hemp fabrics are referred to generally as futomono (太物), meaning "thick materials", with both cotton and hemp yarns being considerably thicker than silk yarns used for weaving. Cotton kimono are specifically referred to in the context of materials as momenfuku (木綿服), "cotton clothes", whereas hemp kimono are known as asafuku (麻服), "hemp clothes", in Japanese, with the character for hemp - asa (麻) - also being used to refer widely to hemp, linen and ramie kimono fabrics.

History

Until the end of the Edo period, the tailoring of both gofuku and futomono fabrics was separated, with silk kimono handled at shops known as 'gofuku dana', and kimono of other fibres sold at shops known as 'futomono dana'. Stores that handled all types of fabric were known as 'gofuku futomono dana', though after the Meiji period, stores only retailing futomono kimono became less profitable in the face of cheaper everyday Western clothing, and eventually went out of business, leaving only gofuku stores to sell kimono - leading to kimono shops becoming known only as gofukuya today.

Kimono fabric production and use

Historically, all fabric bolts woven for kimono were hand-woven, and despite the introduction of machine weaving in the 19th century, a number of well-known kimono fabrics are still produced in this way. Oshima tsumugi is a variety of slub-woven silk produced in Amami Ōshima, known for being highly desirable as a fabric for casual kimono. Bashōfu, a variety of Japanese fibre banana fabric, is also highly desirable as a casual fabric, but produces extremely few bolts of fabric per year due to the growing methods used to produce the plant. The production of these fabrics has experienced a significant downturn in both desirability and craftsmen over time; though in previous decades, up to 20,000 craftspeople were involved in the production of oshima tsumugi, in the present day, just 500 craftspeople are left.[19]

Other varieties of kimono fabric, previously produced out of necessity by the lower and working classes, are produced by hobbyists and craftspeople for their rustic appeal, rather than the necessity of having to make one's own clothes. Saki-ori, a variety of rag-woven fabric historically used to create obi from scraps, were historically produced from old kimono cut into strips roughly 1 cm, with one obi requiring roughly three old kimono to make. These obi were entirely one-sided, and often featured ikat-dyed designs of stripes, checks and arrows, commonly using indigo dyestuff.[20]

Most ikat-woven, indigo-dyed cotton fabrics - known as kasuri - were historically hand-woven, also due to their nature of being produced by the working classes, who through necessity spun and wove their own clothing before the introduction of widely available and cheaper ready-to-wear clothing. Indigo, being the cheapest and easiest-to-grow dyestuff available to many, used due to its specific dye qualities; a weak indigo dyebath could be used several times over to build up a hard-wearing colour, whereas other dyestuffs would be unusable after one round of dyeing. Working class families commonly produced books of hand-woven fabric samples known as shima-cho - literally, "stripe book", as many fabrics were woven with stripes - which would then be used as a dowry for young women and as a reference for future weaving. With the introduced of ready-to-wear clothing, the necessity of weaving one's own clothes died out, leading to many of these books becoming heirlooms instead of working reference guides.[1]

Outside of being re-woven into new fabrics, old kimono have historically been recycled in a variety of ways, depending on the type of kimono and its original use. Formal kimono, made of expensive and thin silk fabrics, would have been re-sewn into children's kimono when they became unusable for adults, as they were typically unsuitable for practical clothing; kimono were shortened, with the okumi taken off and the collar re-sewn to create haori, or were simply cut at the waist to create a side-tying jacket. After marriage or a certain age, young women would shorten the sleeves of their kimono; the excess fabric would be used as a furoshiki (wrapping cloth), could be used to lengthen the kimono at the waist, or could be used to create a patchwork undergarment known as a dounuki. Kimono that were in better condition could be re-used as an under-kimono, or to create a false underlayer known as a hiyoku.

Decorative techniques

.jpg.webp)

Kimono fabrics are often decorated, sometimes by hand, before construction. Customarily, woven patterns are considered more informal within kimono, though for obi, the reverse is true, with dyed patterns being less formal than the sometimes very heavily woven brocade fabrics used in formal obi. Traditionally, woven kimono are matched with obi decorated with dyed patterns, and vice versa, though for all but the most formal kimono, this is more of a general suggestion than a strict rule. Formal kimono are almost-entirely decorated with dyed patterns, commonly along the hem.[21]

Techniques such as resist-dyeing are used commonly on both kimono and obi. These techniques range from intricate shibori tie-dye to rice paste resist-dyeing. Though other forms of resist, such as wax-resist dye techniques, are also seen in kimono, forms of shibori and yūzen - rice-paste resist-dyeing using painted dyes in the open areas - are the most commonly seen.

For repeated patterns covering a large area of base cloth, resist dyeing is typically applied using a stencil, a technique known as katazome. The stencils used for katazome were traditionally made of washi paper layers laminated together with an unripened persimmon tannin dye known as kakishibu.[22]

Other types of rice-paste resist were applied by hand, a technique known as tsutsugaki, commonly seen on both high-quality expensive kimono and rural-produced kimono, noren curtains and other house goods. Though hand-applied resist dyeing on high-end kimono is used so that different colours of dye can be hand-applied within the open spaces left, for rural clothes and fabrics, tsutsugaki was often applied to plain cloth before it was repeatedly dipped in an indigo dye vat, leading to the iconic appearance of white-and-indigo rural clothes, with rice paste sometimes applied over previously open areas to create areas of lighter blue on a darker indigo background.

Another form of textile art used on kimono is shibori, a form of tie dye that ranges from the most basic fold-and-clamp techniques to intricate kanoko shibori dots taking years to fully complete. Patterns are created by a number of different techniques binding the fabric, either with shapes of wood clamped on top of the fabric before dyeing, thread wrapped around minute pinches of fabric, or sections of fabric drawn together with thread and then capped-off using resistant materials such as plastic or (traditionally) the sheaths of the Phyllostachys bambusoides plant (known as either kashirodake or madake in Japan), amongst other techniques.[8] Fabric prepared for shibori is mostly dyed by hand, with the undyed pattern revealed when the bindings are removed from the fabric.

Shibori is found on kimono of a range of formalities, with all-shibori yukata, all-shibori furisode and all-shibori obiage in particular common. Shibori can be further enhanced with the time-consuming use of hand-painted dyes, a technique known as tsujigahana (lit. "flowers at the crossroads"), once a common technique of decoration in the Muromachi period and revived in the 20th century by Japanese dye artist Itchiku Kubota. Due to the time-consuming nature of producing shibori fabrics and the small pool of artists possessing knowledge of the technique, only some varieties are still produced, and brand-new shibori kimono are exceedingly expensive to buy.

Kimono motifs

Many kimono motifs are seasonal, and denote the season in which the kimono can be worn; however, some motifs have no season and can be worn all-year round; others, such as the combination of pine, plum and bamboo - known as the Three Friends of Winter - are auspicious, and thus worn to formal occasions for the entire year. Motifs seen on yukata are commonly seasonal motifs worn out of season, either to denote the spring just passed or the desire for cooler autumn or winter temperatures. Colour also contributes to the seasonality of kimono, with some seasons - such as autumn - generally favouring warmer, darker colours over lighter, cooler ones.

A number of different guides on seasonal kimono motifs exist,[23] with some guides - such as those for tea ceremony in particular - being especially stringent on their reflection of the seasons.[24] Motifs typically represent either the flora, fauna, landscape or otherwise culture of Japan - such as cherry blossoms, a famously seasonal motif worn in spring until just before the actual cherry blossoms begin to bloom, it being considered unlucky to try and 'compete' with the cherries. Motifs are typically worn a few weeks before the official 'start' of any given season, it being considered fashionable to anticipate the coming season.

Construction

Kimono are traditionally made from a single bolt of fabric known as a tanmono, which is roughly 11.5m long and 36 cm wide for women,[1] and 12.5m long and 42 cm wide for men. The entire bolt is used to make one kimono, and some men's tanmono are woven to be long enough to create a matching haori jacket and juban as well. Some custom bolts of fabric are produced for especially tall or heavy people, such as sumo wrestlers, who must have kimono custom-made by either joining multiple bolts, weaving custom-width fabric, or using non-standard size fabric.[25] Kimono linings are made from bolts of the same width.

Kimono have a set method of construction, which allows the entire garment to be taken apart, cleaned and resewn easily. As the seam allowance on nearly every panel features two selvedges that will not fray, the woven edges of the fabric bolt are retained when the kimono is sewn, leading to large and often uneven seam allowances; unlike Western clothing, the seam allowances are not trimmed down, allowing for a kimono to be resewn to different measurements without the fabric fraying at the seams; for children's kimono, tucks may be sewn into the waist, shoulders and sleeves, which are then let out as the child grows, as even children's kimono are made from adult-width bolts.

Historically, kimono were taken apart entirely to be washed - a process known as arai-hari. Once cleaned, the fabric would be resewn by hand;[1] this process, though necessary in previous centuries, is uncommon in modern-day Japan, as it is relatively expensive.

Despite the expense of hand-sewing, however, some modern kimono, including silk kimono and all formal kimono, are still hand-sewn entirely; even machine-sewn kimono require some degree of hand-sewing, particularly in finishing the collar, the hem, and the lining, if present. Hand-sewn kimono are usually sewn with a single running stitch roughly 3 millimetres (0.12 in) to 4 millimetres (0.16 in) long, with stitches growing shorter around the collar area for strength. Kimono seams, instead of being pressed entirely flat, are pressed to have a 'lip' of roughly 2 millimetres (0.079 in) (known as the kise) pressed over each seam. This disguises the stitches, as hand-sewn kimono are not tightly sewn, rendering the stitches visible if pressed entirely flat.

Terms

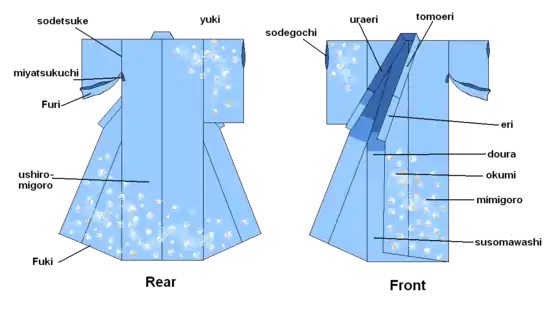

A number of different terms are used to refer to the different parts of a kimono. Kimono that are lined are known as awase kimono, whereas unlined kimono are known as hitoe kimono; partially lined kimono — with lining only at the sleeve cuff, the back of the sleeve, the lower chest portion of the dōura and the entirety of the hakkake — are known as dou-bitoe (lit., "chest-single-layer") kimono.[26] Some fully lined kimono do not have a separate lower and upper lining, and are instead lined with solid panels on the okumi, the maemigoro and the ushiromigoro.

These terms refer to parts of a kimono:

- Dōura (胴裏): the upper lining of a kimono.

- Hakkake (八掛): the lower lining of a kimono.

- Eri (衿): the collar.

- Fuki (袘): the hem guard.

- Furi (振り): lit., "dangling" — the part of the sleeve left hanging below the armhole.

- Maemigoro (前身頃): lit., "front body" — the front panels on a kimono, excluding the okumi. The panels are divided into the "right maemigoro" and "left maemigoro".

- Miyatsukuchi (身八つ口): the opening under the sleeve on a woman's kimono.

- Okumi (衽): the overlapping front panel.

- Sode (袖): the entire sleeve.

- Sodeguchi (袖口): the wrist opening of the sleeve.

- Sodetsuke (袖付): the kimono armhole.

- Susomawashi (裾回し): lower lining.

- Tamoto (袂): the sleeve pouch of a kimono.

- Tomoeri (共衿): lit., "over-collar" — the collar cover sewn on top of the uraeri.

- Uraeri (裏襟): lit., "neckband lining" — the inner collar.

- Ushiromigoro (後身頃): lit., "back body" — the back panels. The back panels consist of the "right ushiromigoro" and "left ushiromigoro".

Evolution of kimono construction

Though the basic shape of the kimono has not changed in centuries, proportions have, historically, varied in different eras of Japanese history. Beginning in the later Heian period, the hitoe - an unlined robe worn as underwear - became the predominant outerwear garment for both men and women, known as the kosode (lit. "small sleeve"). Court-appropriate dress continued to resemble the previous eras.

By the beginning of the Kamakura period, the kosode was an ankle-length garment for both men and women, and had small, rounded sleeves that were sewn to the body of the garment. The obi was a relatively thin belt tied somewhat low on the waist, usually in a plain bow, and was known as a hoso-obi.[27] During this time period, the fashion of wearing a kosode draped around the shoulders, over the head, or as the outermost garment stripped off the shoulders and held in place by the obi, led to the rise of the uchikake - a heavily decorated over-kimono, stemming from the verb "uchikake-ru" (lit., "to drape upon"), worn unbelted over the top of the kosode - becoming popular as formal dress for the upper classes.[1]:39

In the following centuries, the kosode mostly retained its small, narrow and round-sleeved nature, with the length of women's sleeves gradually increasing over time and eventually becoming mostly detached from the body of the garment below the shoulders. The collar on both men's and women's kosode retained its relatively long and wide proportions, and the okumi front panel kept its long, shallow angle towards the hem. During the Edo period, the kosode had developed roughly modern kimono proportions, though variety existed until roughly the mid- to later years of the era.[28] Men's sleeves continued to be sewn shut to the body down most of their length. Sleeves for both men and women grew in proportion to be of roughly equal width to the body panels, and the collar for both men's and women's kimono became shorter and narrower.

In the present day, both men's and women's kimono retain some historical features - for instance, women's kimono, which trailed along the floor throughout certain eras, ideally should be as tall as the person wearing them, with the excess length folded and tied underneath the obi in a hip fold known as the ohashori. Formal women's kimono also retain the wider collar of previous eras, though it is always folded in half lengthwise before wearing - a style known as hiro-eri (lit. "wide collar", as opposed to bachi-eri, a normal width collar).[29]

Cost

Both men's and women's brand-new kimono can range in expense, from the relatively cheap nature of second-hand garments, to high-end artisan pieces costing as much as US$50,000[30] (not allowing for the cost of accessories).

The high expense of some hand-crafted brand-new kimono reflects the traditional kimono making industry, where the most skilled artisans practice specific, expensive and time-consuming techniques, known to and mastered only by a few. These techniques, such as hand-plied bashofu fabrics and hand-tied kanoko shibori dotwork dyeing, may take over a year to finish. Kimono artisans may be made Living National Treasures in recognition of their work, with the pieces they produce being considered culturally important.

Even kimono that have not been hand-crafted will constitute a relatively high expense when bought new, as even for one outfit, a number of accessories of the right formality and appearance must be bought. Not all brand-new kimono originate from artisans, and mass-production of kimono - mainly of casual or semi-formal kimono - does exist, with mass-produced pieces being mostly cheaper than those purchased through a gofukuya (kimono shop, see below).

Though artisan-made kimono are some of the most accomplished works of textile art on the market, many pieces are not bought solely for appreciation of the craft. Unwritten social obligations to wear kimono to certain events - weddings, funerals - often leads consumers to purchase artisan pieces for reasons other than personal choice, fashion sense or love of kimono:

[Third-generation yūzen dyer Jotaro Saito] believes we are in a strange age where people who know nothing about kimono are the ones who spend a lot of money on a genuine handcrafted kimono for a wedding that is worn once by someone who suffers wearing it, and then is never used again.[19]:134

The high cost of most brand-new kimono reflects in part the pricing techniques within the industry. Most brand-new kimono are purchased through gofukuya, where kimono are sold as fabric rolls only, the price of which is often left to the shop's discretion. The shop will charge a fee separate to the cost of the fabric for it to be sewn to the customer's measurements, and fees for washing the fabric or weatherproofing it may be added as another separate cost. If the customer is unfamiliar with wearing kimono, they may hire a service to help dress them; the end cost of a new kimono, therefore, remains uncertain until the kimono itself has been finished and worn.[16]

Gofukuya are also regarded as notorious for sales practices seen as unscrupulous and pressuring:

Many [Japanese kimono consumers] feared a tactic known as kakoikomi: being surrounded by staff and essentially pressured into purchasing an expensive kimono...Shops are also renowned for lying about the origins of their products and who made them...[My kimono dressing (kitsuke) teacher] gave me careful instructions before we entered the [gofukuya]: 'do not touch anything. And even if you don’t buy a kimono today, you have to buy something, no matter how small it is.’[16]:115-117

In contrast, kimono bought by hobbyists are likely to be less expensive, purchased from second-hand stores with no such sales practices or obligation to buy. Hobbyists may also buy cheaper synthetic kimono (marketed as 'washable') brand-new. Some enthusiasts also make their own kimono; this may be due to difficulty finding kimono of the right size, or simply for personal choice and fashion.

Second-hand items are seen as highly affordable; costs can be as little as ¥100 (about US$0.90) at thrift stores within Japan, and certain historic kimono production areas around the country - such as the Nishijin district of Kyoto - are well known for their second-hand kimono markets. Kimono themselves do not go out of fashion, making even vintage or antique pieces viable for wear, depending on condition.[31]

However, even second-hand women's obi are likely to remain somewhat pricey; a used, well-kept and high-quality second-hand obi can cost upwards of US$300, as they are often intricately woven, or decorated with embroidery, goldwork and may be hand-painted. Men's obi, in contrast, retail much cheaper, as they are narrower, shorter, and have either very little or no decoration, though high-end men's obi can still retail at a high cost equal to that of a high-end women's obi.

Types of kimono

Formality

Kimono range in variation from extremely formal to very casual. The formality of a woman's kimono is determined mostly by pattern placement, decoration style, fabric choice and colour. The formality of men's kimono is determined more by fabric choice and coordination elements (hakama, haori, etc.) than decoration, as men's kimono tend to be one colour with motifs only visible when looked at closely.

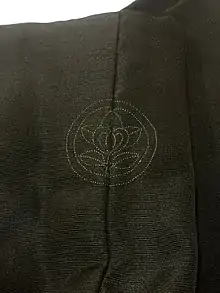

In both cases, formality is also determined by the number and type of kamon (crests). Five crests (itsutsu mon) are the most formal, three crests (mitsu mon) are mid-formality, and one crest (hitotsu mon) is the least formal, used for occasions such as tea ceremony.

The type of crest adds formality as well. A "full sun" (hinata) crest, where the design is outlined and filled in with white, is the most formal type. A "mid-shadow" (nakakage) crest is mid-formality, with only the outline of the crest visible in white. A "shadow" (kage) crest is the least formal, with the outline of the crest relatively faint. Shadow crests may be embroidered onto the kimono, and full-embroidery crests, called nui mon, are also seen.[32]

Formality can also be determined by the type and colour of accessories, such as weave of obijime and the style of obiage.

Women's kimono

The typical woman's kimono outfit may consist of up to twelve or more separate pieces; some outfits, such as formal wedding kimono, may require the assistance of licensed kimono dressers, though usually, this is due to the wearer's inexperience with kimono and the difficult-to-tie nature of some formal obi knots. Most professional kimono dressers are found in Japan, where they work out of hair salons, as specialist businesses, or freelance.

Choosing an appropriate type of kimono requires knowledge of the wearer's age, occasionally marital status (though less so in modern times), the formality of the occasion at hand, and the season. Choice of fabric is also dependent on these factors, though some fabrics - such as crepe and rinzū - are never seen in certain varieties of kimono, and some fabrics such as shusu (heavy satin) silk are barely ever seen in modern kimono or obi altogether, having been more popular in previous eras than in the present-day.

Though length of kimono, collar style and the way the sleeves are sewn on varies for susohiki kimono, in all other types of women's kimono, the construction generally does not change; the collar is set back slightly into the nape of the neck, the sleeves are only attached at the shoulder, not all the way down the sleeve length, and the kimono's length from shoulder to hem should generally equal the entire height of the woman wearing it, to allow for the ohashori hip fold.

Sleeve length increases for furisode - young women's formal dress - but young women are not limited to wearing only furisode, as outside of formal occasions that warrant it, can wear all other types of women's kimono such as irotomesode and komon.

Yukata

Yukata (浴衣) are casual cotton summer kimono. Yukata were originally very simple indigo and white cotton kimono, little more than a bathrobe worn either within the house, or for a short walk locally; yukata were also worn by guests at inns, with the design of the yukata displaying the inn a person was staying at. From roughly the mid-1980s onwards, they began to be produced in a wider variety of colours and designs, responding to demand for a more casual kimono that could be worn to a summer festival.

In the present day, most yukata are brightly coloured (for women) featuring large motifs from a variety of different seasons. They are worn with hanhaba obi (half-width obi) or heko obi (a soft, sash-like obi), and are often accessorised with colourful hair accessories. Yukata are always unlined, and it is possible to wear a casual nagoya obi with a high-end, more subdued yukata.

Furisode

Furisode (振袖) (lit., "swinging sleeve") kimono are the most formal kimono for a young, often unmarried, woman. They are decorated with colourful patterns across the entirety of the garment, and usually worn to seijin shiki (Coming of Age Day) or weddings, either by the bride herself or an unmarried younger female relative.

The sleeves of the furisode average at between 100–110 cm in length. Chu-furisode (mid-size furisode) have shorter sleeves at roughly 80 cm in length; most chu-furisode are vintage kimono, as in the modern day furisode are not worn often enough to warrant buying a more casual form of the dress, though brand-new chu-furisode do exist.

Hōmongi

Hōmongi (訪問着) (lit., "visiting wear") are distinguished in their motif placement - the motifs flow across the back right shoulder and back right sleeve, the front left shoulder and front left sleeve, and across the hem, higher at the left than the right. They are always made of silk, and are considered more formal than the tsukesage.

Hōmongi are first roughly sewn up, the design sketched onto the fabric, before it is taken apart to be dyed again. The hōmongi's close relative, the tsukesage, has its patterns dyed on the bolt before sewing up. This method of production can usually distinguish the two, as the motifs on a hōmongi are likely to cross fluidly over seams in a way a tsukesage generally will not.[33] However, the two can prove near-indistinguishable at times.

Hōmongi may be worn by both married and unmarried women; often friends of the bride will wear hōmongi at weddings (except relatives) and receptions. They may also be worn to formal parties.

Iromuji

Iromuji (色無地) (lit., "solid colour") are monochromatic, undecorated kimono mainly worn to tea ceremonies. Despite being monochromatic, iromuji may feature a woven design; iromuji suitable for autumn are often made of rinzu silk. Iromuji are typically worn for tea ceremony, as the monochrome appearance is considered to be unintrusive to the ceremony itself. Some edo komon with incredibly fine patterns are also considered suitable for tea ceremony, as from a distance they are visually similar to iromuji. Iromuji may occasionally have one kamon, though likely no more than this, and are always made of silk. Shibori accessories such as obiage are never worn with iromuji if the purpose of wear is a tea ceremony; instead, flat and untextured silks are chosen for accessories.

Edo komon

Edo komon (江戸小紋) are a type of komon characterised by an extremely small repeating pattern, usually done in white on a coloured background. The edo komon dyeing technique originated within the samurai classes during the Edo period. Edo komon are of a similar formality to iromuji, and edo komon with one kamon can be worn as low-formality visiting wear; because of this, they are always made of silk, unlike regular komon.

Mofuku

Mofuku (喪服) are a category of kimono and kimono accessories suitable for mourning; mofuku kimono, obi and accessories for both men and women are characterised by their plain, solid black appearance. Mofuku kimono are plain black silk with five kamon, worn with white undergarments and white tabi. Men wear a kimono of the same kind, with a subdued obi and a black-and-white or black-and-grey striped hakama, worn with black or white zōri.

A completely black mourning ensemble for women - a plain black obi, black obijime and black obiage - is usually reserved for those closest to the deceased. Those further away will wear kimono in dark and subdued colours, rather than a plain black kimono with a reduced number of crests. In time periods when kimono were worn more often, those closest to the deceased would slowly begin dressing in coloured kimono over a period of weeks after the death, with the obijime being the last thing to be changed over to colour.[1]

Kurotomesode

Kurotomesode (黒留袖) (lit., "black short-sleeve") kimono are formal kimono with a black background and a design along the hem, worn to formal events such as weddings and wedding parties. The design is only present along the hem; the further up the body this design reaches, the younger the wearer is considered to be, though for a very young woman an irotomesode may be chosen instead, kurotomesode being considered somewhat more mature. The design is either symmetrically placed on the fuki and okumi portions of the kimono, or asymmetrically placed along the entirety of the hem, with the design being larger and higher-placed at the left side than the right. Vintage kimono are more likely to have the former pattern placement than the latter, though is not a hard rule.

Kurotomesode are always made of silk, and may have a hiyoku - a false lining layer - attached, occasionally with a slightly padded hem. A kurotomesode usually has between 3 and 5 crests; a kurotomesode of any number of crests outranks an irotomesode with less than five. Kurotomesode, though formalwear, are not allowed at the royal court, as black is the colour of mourning, despite the colour designs decorating the kimono itself; outside of the royal court, this distinction for kurotomesode does not exist. Kurotomesode are never made of flashy silks such as rinzū, but are instead likely to be a matte fabric with little texture.

Irotomesode

Irotomesode (色留袖) (lit., "colour short-sleeve") kimono are slightly lower-ranking formal kimono with roughly the same pattern placement as kurotomesode, but on a coloured background. Irotomesode, though worn to formal events, may be chosen when a kurotomesode would make the wearer appear to be overdressed for the situation. The pattern placement for irotomesode is roughly identical to kurotomesode, though patterns seen along the fuki and okumi may drift slightly into the back hem itself. Irotomesode with five kamon are of the same formality as any kurotomesode. Irotomesode may be made of figured silk such as rinzū.

Tsukesage

Tsukesage (付け下げ) are lower-ranking formalwear, a step below hōmongi, wherein the motifs generally do not cross over the seams of each kimono panel, but have the same placement as a hōmongi. Similarities between the two often lead to confusion, with some tsukesage near-indistinguishable from hōmongi. Tsukesage can have between one and three kamon, and can be worn to parties, but not ceremonies or highly formal events.

Uchikake

Uchikake (打ち掛け) are highly formal kimono worn only in bridalwear or on stage. The name uchikake comes from the verb "uchikake-ru", "to drape upon", originating in roughly the 16th century from a fashion of the ruling classes of the time to wear kimono (then called kosode, lit. "small sleeve") unbelted over the shoulders of one's other garments;[1]:34 the uchikake progressed into being an over-kimono worn by samurai women before being adopted some time in the 20th century as bridalwear.

Uchikake are worn in the same manner in the present day, though unlike their 16th-century counterparts, could not double as a regular kimono due to their typically heavily decorated, highly formal and often heavily padded nature. Uchikake are designed to trail along the floor as a sort of coat. Bridal uchikake are typically red or white, and often decorated heavily with auspicious motifs. Because they are not designed to be worn with an obi, the designs cover the entirety of the back.

Shiromuku

Shiromuku (白無垢) (lit., "white pure-innocence") are the pure-white wedding kimono worn by brides for a traditional Japanese Shinto wedding ceremony. Comparable to an uchikake and sometimes described as a white uchikake, a shiromuku is worn for the part of the wedding ceremony, symbolising the purity of the bride coming into the marriage. The bride may later change into a red uchikake after the ceremony to symbolise good luck.

A shiromuku will form part of a bridal ensemble with matching or coordinating accessories, such as a bridal katsura, a set of matching kanzashi (usually mock-tortoiseshell), and a sensu fan tucked into the kimono. Due to the expensive nature of traditional bridal clothing, few are likely to buy brand-new shiromuku; it is not unusual to rent kimono for special occasions, and Shinto shrines are known to keep and rent out shiromuku for traditional weddings. Those who do possess shiromuku already are likely to have inherited them from close family members.

Susohiki/Hikizuri

Susohiki (lit. "trailing skirt") (also known as hikizuri) kimono are extremely long kimono worn by geisha, maiko, actors in kabuki and people performing traditional Japanese dance. A susohiki can be up to 230 cm long, and are generally no shorter than 200 cm from shoulder to hem; this is to allow the kimono to trail along the floor.

Susohiki, apart from their extreme length, are also sewn differently to normal kimono due to the way they are worn.[34] The collar on a susohiki is sewn further and deeper back into the nape of the neck, so that it can be pulled down much lower without causing the front of the kimono to ride up. The sleeves are set unevenly onto the body, shorter at the back than at the front, so that the underarm does not show when the collar is pulled down.

Susohiki are also tied differently when they are put on - whereas regular kimono are tied with a visible ohashori, and the side seams are kept straight, susohiki are pulled up somewhat diagonally, to emphasise the hips and ensure the kimono trails nicely on the floor. A small ohashori is tied, larger at the back than the front, but it wrapped against the body with a momi (lit. "red silk") wrap, which is then covered by the obi, rendering it not visible.[note 1]

Jūnihitoe

Jūnihitoe (十二単) (lit., "twelve layers") describes the layered garments worn by court ladies during the Heian period. The jūnihitoe consisted of up to twelve layered garments, with the innermost garment being the kosode - the small-sleeved kimono prototype which would eventually go on to become the outermost garment worn.

The total weight of the jūnihitoe could be up to 20 kg. The garments were decorated in relatively large motifs, with a more important aspect being the numerous recorded colour combinations an outfit could have.

An important accessory of this outfit was an elaborate hand fan, which could be tied together by tassels tied onto the end fan bones. These fans were made of cypress wood entirely, with the design painted onto the wide, flat bones themselves, and were known as hiōugi.

No garments from the Heian period survive, and today the jūnihitoe can only be seen as a reproduction in museums, movies, festivals and demonstrations. The Imperial Household still officially uses them at some important functions, such as the coronation of the new Empress.

Men's kimono

_MET_DP701232.jpg.webp)

In contrast to women's kimono, men's kimono outfits are far simpler, typically consisting of five pieces, excluding footwear.

Men's kimono sleeves are attached to the body of the kimono with no more than a few inches unattached at the bottom, unlike the women's style of very deep sleeves mostly unattached from the body of the kimono. Men's sleeves are less deep than women's kimono sleeves to accommodate the obi around the waist beneath them, whereas on a woman's kimono, the long, unattached bottom of the sleeve can hang over the obi without getting in the way.

In the modern era, the principal distinctions between men's kimono are in the fabric. The typical men's kimono is a subdued, dark colour; black, dark blues, greens, and browns are common. Fabrics are usually matte. Some have a subtle pattern, and textured fabrics are common in more casual kimono. More casual kimono may be made in slightly brighter colours, such as lighter purples, greens and blues. Sumo wrestlers have occasionally been known to wear quite bright colours such as fuchsia.

Related garments

Though the kimono is the national dress of Japan, it has never been the sole item of clothing worn throughout Japan; even before the introduction of Western dress to Japan, many different styles of dress were worn, such as the attus of the Ainu people and the ryusou of the Ryukyuan people. Though similar to the kimono, these garments are distinguishable by their separate cultural heritage, and are not considered to be simply 'variations' of kimono such as the clothing worn by the working class is considered to be.

Some related garments still worn today were the contemporary clothing of previous time periods, and have survived on in an official and/or ceremonial capacity, worn only on certain occasions by certain people.

Religious garments

Some related garments are specific to certain religious roles. The chihaya (ちはや/襅) is worn only by kannushi and miko in some Shinto shrine ceremonies, and the samue (作務衣) is the everyday clothing for a male Zen Buddhist lay-monk, and the favoured garment for komusō monks playing the shakuhachi.

Ceremonial and professional garments

Jittoku (十徳) are a style of haori worn only by some high-ranking male practitioners of tea ceremony. Jittoku are made of unlined silk gauze, fall to the hip, and have sewn himo ties at the front made of the same fabric as the main garment. The jittoku has a wrist opening that is entirely open along the sleeve's vertical length. The garment originated in the Kamakura Period (1185-1333 CE), and are worn without hakama.

For formal ceremonies, members of Japanese nobility will wear certain types of antiquated kimono such as the suikan (水干) and the jūnihitoe (十二単). Outside of nobility, jūnihitoe are only found in dress-up (henshin) studios, or in museums as recreations; no examples of Heian period clothing exist, and only small and fragile samples of the fabrics used in those times survive.

Bridalwear

Brides in Japan who opt for a traditional ceremony will wear specific accessories and types of kimono, which may be changed and switched out for certain parts of the ceremony; for instance, the wata bōshi hood is removed during the ceremony, and uchikake are worn over the top of shiromuku bridal kimono once the ceremony has been completed, usually at the reception. Many bridalwear traditions, such as the addition of a small (fake) dagger, are amalgams and facsimiles of samurai dress from previous eras.

- Tsunokakushi (角隠し, lit. "horn-hiding")

- Tsunokakashi is a style of headwear worn by brides in traditional Shinto wedding ceremonies. Tsunokashi may be made of white silk and worn with the bride's white shiromuku wedding kimono, or they may be made of coloured materials to match or coordinate when the bride opts for a non-shiromuku style. Tsunokakashi, unlike wata bōshi, do not cover the high topknot formed by the bride's takashimada-style wig.

- According to folk etymology, the headwear is worn to hide the bride's horns of jealousy and selfishness; however, this headdress was originally a simpler cap worn to keep the dirt and dust off a woman's hairstyle when travelling.[36] The custom spread from married women in samurai families in the Muromachi and Momoyama periods to younger women of lower classes during the Edo period.

- Wata bōshi (綿帽子, lit "cotton hat")

- Wata bōshi is a style of full-coverage hood also worn by the bride in traditional Shinto weddings. The wata bōshi is always white and worn with shiromuku. Wata bōshi entirely cover the bride's hairstyle.[37]

- Takashimada (高島田)

- takashimada katsura are the style of shimada wig worn by brides. This wig resembles the style worn by geisha, with a few key differences; namely that the wig appears to be shorter and fuller, with the mage (bun) at the back placed much higher on the head. The takashimada is worn with a matching set of tortoiseshell or faux-tortoiseshell kanzashi hair accessories

- Kanzashi (簪)

- Kanzashi hair ornaments, made of tortoiseshell or faux-tortoiseshell, are worn with the takashimada wig. These hair accessories will come in a matching set, including a highly decorated kushi comb and kogai hair stick, and a number of bira-bira-style kanzashi, often decorated with flowers in either tortoiseshell or metal and coral or coral-substitute.

- Sensu (扇子)

- Sensu folding hand fans, in either entirely gold or silver leaf, are worn tucked into the obi.

- Futokorogatana (懐刀)

- Futokorogatana, lit. "chest sword", are small daggers tucked into the collar, often held inside a small, decorative purse made of brocade fabric. Similar to a Kaiken.

- Hakoseko (箱迫)

- Hakoseko are small, highly decorative purses worn with wedding kimono. These are also made out of decorative brocade fabric, often with tassels on the ends of the purse, and usually contain some combination of a small mirror and a comb.

Accessories

There are a number of accessories that can be worn with the kimono, and these vary by occasion and use. Some are ceremonial, or worn only for special occasions, whereas others are part of dressing in kimono and are used in a more practical sense.

Both geisha and maiko wear variations on common accessories that are not found in everyday dress. As an extension of this, many practitioners of Japanese traditional dance wear similar kimono and accessories to geisha and maiko.

For certain traditional holidays and occasions some specific types of kimono accessories are worn. For instance, okobo, also known as pokkuri, are worn by girls for shichi-go-san, alongside brightly coloured furisode. Okobo are also worn by young women on seijin no hi (Coming of Age Day).

- Datejime (伊達締め) or datemaki (伊達巻き)

- A wide undersash used to flatten and keep in place the kimono and/or the nagajuban when tied. Datejime can be made of a variety of fabrics, including silk, linen and elastic.[38]

A traditional silk datejime with stiffer middle and softer ends

A traditional silk datejime with stiffer middle and softer ends

- Fā (ファー)

- A fur collar, boa, stole, and even a muff, worn by women over a kimono; white fur stoles are usually worn by young women on their Coming of Age Day, whereas other colours are likely to be worn by older women to keep warm.

- Geta (下駄)

- Wooden sandals worn by men and women with yukata and other casual kimono. They are usually made of a lightweight wood such as paulownia, and come in a variety of styles, such as ama geta ("rain geta", covered over the feet) and tengu geta (with just one prong on the sole instead of two).

- Hachimaki (鉢巻)

- Traditional Japanese stylized headband, worn to keep sweat off of one's face. In Japanese media, it is used as a trope to show the courage of the wearer, symbolising the effort put into their strife, and in kabuki, it can symbolise a character sick with love.

- Hadagi (肌着)

- A type of Japanese attire, similar to a kosode or a shirt, employed by the samurai class mainly during the Sengoku period (16th century) of Japan. The Hadagi is generally the same as a normal juban (shirt), measuring around two to four sun in length. Hadagi are made of either linen, silk crepe, or cotton cloth. Because Hadagi are only worn in cold climates, lined Hadagi are preferred over a single-layer garment. The sleeves on this type of shirt are rather narrow, and are at times omitted altogether.

- Hakama (袴)

- A divided (umanori-bakama) or undivided skirt (andon-bakama) which resembles a wide pair of trousers. Hakama were historically worn by both men and women, and in modern day can be worn to a variety of formal or informal events. A hakama is typically pleated at the waist and fastened by waist ties over the obi. For women, shorter kimono may be worn underneath the hakama for ease of movement.

Women at a graduation ceremony, featuring hakama with embroidered flowers, and demonstrating the waistline

Women at a graduation ceremony, featuring hakama with embroidered flowers, and demonstrating the waistline - Hakama are worn in several budō arts such as aikido, kendo, iaidō and naginata. They are also worn by Miko in Shintō shrines.

- Hakama boots (袴ブーツ)

- A pair of boots (leather or faux leather), with low-to-mid heels, worn with a pair of hakama (a pair of traditional Japanese trousers); boots are a style of footwear that came in from the West during the Meiji Era; worn by women while wearing a hakama, optional footwear worn by young women, students and teachers at high-school and university graduation ceremonies, and by young women out celebrating their Coming of Age at shrines, etc., often with a hakama with furisode combination.

- Hakoseko (筥迫, lit. "boxy narrow thing")

- A small box-shaped billfold accessory; sometimes covered in materials to coordinate with the wearer's kimono or obi. Fastened closed with a cord, and carried tucked-within a person's futokoro, the space within the front of kimono collar and above the obi. Used for formal occasions that require traditional dress, such as a traditional Shinto wedding or a child's Shichi-Go-San ceremony. Originally used for practical uses, such as carrying around a woman's beni ita(lipstick), omamori (an amulet/talisman), kagami (mirror), tenugui (handkerchief), coins, and the like, it now has a more of a decorative role.

- Hanten (袢纏, lit. "half-wrap")

- The worker's version of the more formal haori. As winterwear, it is often padded for warmth, giving it insulating properties, as opposed to the somewhat lighter happi. It could be worn outside in the wintertime by fieldworkers out working in the fields, by people at home as a housecoat or a cardigan, and even slept-in over one's bedclothes.

- Haori (羽織)

- A hip- or thigh-length kimono-like overcoat with straight, rather than overlapping, lapels. Haori were originally worn by men until they were popularised as women's wear as well by geisha in the Meiji period. The jinbaori (陣羽織) was specifically made for armoured samurai to wear.

_MET_DP330781.jpg.webp) Haori

Haori - Haori himo (羽織紐)

- A tasseled, woven string fastener for haori. The most formal colour is white (see also fusa above).

- Happi (法被)

- A type of haori traditionally worn by shop keepers, sometimes uniform between the helpers of a shop (not unlike a propaganda kimono, but for advertising business), and is now associated mostly with festivals.

- Haramaki (腹巻, lit. "belly wrap")

- Are items of Japanese clothing that cover the stomach. They are worn for health, fashion and superstitious reasons.

- Hifu (被布)

- Originally a kind of padded over-kimono for warmth, this has evolved into a sleeveless over-kimono like a padded outer vest or pinafore (also similar to a sweater vest or gilet), worn primarily by girls on formal outings such as the Shichi-Go-San ceremony for children aged seven, five, and three.

- Hirabitai (枚額)

- A decoration, part of a Kamiagegu, and similar to a Kanzashi, worn on the front of the hair, above the forehead,held into the hair by pins worn by Edo-era aristocratic women in court, like a Tiara, with their Jūnihitoe robes.

- Jika-tabi (地下足袋)

- A modification of the usual split-toe tabi sock design for use as a shoe, complete with rubber sole. Invented in the early 20th century.

- Jinbei (甚平)

- Traditional Japanese loose-woven two-piece clothing, consisting of a robe-like top and shorts below the waist. Worn by men, women, boys, girls, and even babies, during the hot, humid summer season, in lieu of kimono.

- Hadajuban (肌襦袢)

- A thin garment similar to a nagajuban; it is considered to be "kimono underwear", worn in direct contact with the skin, and has tube-shaped sleeves. It is worn with a slip-like wrap tied around the waist, with the nagajuban worn on top.[39][40]

- Inro (印籠)

- An traditional Japanese case for holding small objects, suspended from the obi worn around the waist when wearing kimono. They are often highly decorated, in a variety of materials and techniques, often using lacquer. (See also netsuke and ojime)

- Ka (架, lit. "rack")

- A rack or stand used for holding and displaying kimono.

- Kappōgi (割烹着, lit. "cooking wear")

- A type of gown-like apron; first designed to protect kimono from food stains, it has baggy sleeves, is as long as the wearer's knees, and fastens with strips of cloth ties that are tied at the back of the neck and the waist.Particularly used when cooking and cleaning, it is worn by Japanese housewives, lunch ladies, cleaners, etc.

- Kasa (傘)

- A traditional Japanese oil-paper umbrella/parasol, these umbrellas as typically crafted from one length of bamboo split finely into spokes. See also Gifu umbrellas.

- Kinchaku (巾着)

- A traditional Japanese drawstring bag or pouch, worn like a purse or handbag (vaguely similar to the English reticule), for carrying around personal possessions (money, etc). A kind of sagemono.

- Kimono slip (着物スリップ, kimono surippu)

- A one-piece undergarment combining the hadajuban and the susoyoke.[41][42]

- Koshihimo (腰紐, lit., "hip cord")

- A narrow strip of fabric used to tie the kimono, nagajuban and ohashori in place while dressing oneself in kimono. They are often made of silk or wool.

- Michiyuki (道行き)

- A traditional Japanese overcoat (not to be confused with a haori or a hifu), characterised with a signature square neckline formed by the garment's front overlap. It is fastened at the front with snaps or buttons, and is often worn over the kimono for warmth, protection from the weather or as a casual housecoat. Some michiyuki will include a hidden pocket beneath the front panel, and they are typically thigh- or even knee-length.

- Nagajuban (長襦袢, lit., "long underwear")

- A long under-kimono worn by both men and women beneath the main outer garment.[43] Since silk kimono are delicate and difficult to clean, the nagajuban helps to keep the outer kimono clean by preventing contact with the wearer's skin. Only the collar edge of the nagajuban shows from beneath the outer kimono.[44] Many nagajuban have removable collars, to allow them to be changed to match the outer garment, and to be easily washed without washing the entire garment. They are often as beautifully ornate and patterned as the outer kimono. Since men's kimono are usually fairly subdued in pattern and colour, the nagajuban allows for discreetly wearing very striking designs and colours.[45]

- Nemaki (寝間着)

- Japanese nightclothes.

- Netsuke (根付) or Netsuke (根付け)

- An ornament worn suspended from the men's obi, serving as a cordlock or a counterweight. (See also inro and ojime).

- Obi-age (帯揚げ)

- A scarf-like sash worn tied above the obi, either knotted or tucked into the garment's collars. The obi-age has the dual purpose of hiding the obi-makura and providing a colour contrast against the obi. Obi-age are often silk, and are typically worn with more formal varieties of kimono. Obi-age can be plain-dyed silk, but are often decorated with shibori tie-dyeing; for maiko, obi-age are only ever red with a gold or silver foil design.

Back of a woman wearing a kimono with the obi sash tied in the tateya musubi style

Back of a woman wearing a kimono with the obi sash tied in the tateya musubi style - Obidome (帯留め)

- A decorative fastening accessory piece, strung onto the obijime. For maiko, the obi-dome is commonly the most expensive part of the outfit, as they are usually hand-made from precious stones and metal such as gold or silver. Some obijime are woven specially to allow the obidome to be pinned on.

- Obi-ita (帯板)

- A thin, stiff board, commonly inserted behind the obi at the front, helping to give a smooth, uniform appearance.

- Obijime (帯締め)

- A decorative woven or padded cord used to assist in tying more complex bows with the obi, also worn as simple decoration on the obi itself. It can be tied at the front, and the ends tucked into the band itself, or tied at the back, in the case of being worn with an obi-dome.

- An ojime (see below) can be used to fasten the obijime in place (similar to a netsuke), and also serves as a decoration.

- Obi-makura (帯枕)

- Padding used to put volume under the obi knot (musubi); to support the bows or ties at the back of the obi and keep them lifted. An essential part of the common taiko musubi ("drum knot").

- Ojime (緒締め)

- A type of bead used to fasten a obijime in place, like a cordlock. They are also worn between the inrō and netsuke and are typically under an inch in length. Each is carved into a particular shape and image, similar to the netsuke cordlock, though smaller.

- Sarashi (晒し)

- Sarashi is Japanese for "bleached cloth", usually cotton, or less commonly linen. Such cloth may be wrapped around the body (under a kimono), usually around the chest (similar to a girdle). Sometimes it is wrapped around below the belly during pregnancy, or around the waist after the birth of a child. It is used by men and women. The whiteness and purity of the cloth has ritual significance, therefore it may also be used in rituals.

- Sensu (扇子)

- A handheld fan (either an ōgi (扇) or an uchiwa (団扇)), generally made of washi paper coated in paint, lacquer or gold leaf, with bamboo spines. As well as being used for cooling-off, sensu fans are used as dancing props, and are often worn tucked into the obi.

- Setta (雪駄)

- A flat, thick-bottomed sandal made of bamboo and straw with leather soles, and with metal spikes protruding from the heel of the sole to prevent slipping on ice.

- Susoyoke (裾除け)

- A thin half-slip-like piece of underwear, like a petticoat, worn by women under their nagajuban.[39][46]

- Suzu (鈴)

- A round, hollow Japanese Shinto bell or chime. They are somewhat like a jingle bell in form, though the materials produce a coarse, rolling sound. Suzu come in many sizes, ranging from tiny ones on good luck charms (called omamori (お守り)) to large ones at shrine entrances. As an accessory to kimono wear, suzu are often part of kanzashi.

- Tabi (足袋)

- Ankle-high, divided-toe socks usually worn with zōri or geta. There also exist sturdier, boot-like jikatabi, which are used for example to fieldwork.

- Tasuki (襷)

- A pair of sashes that loop over each shoulder and across the back, used for holding up kimono sleeves when working.

- Tenugui (手拭い, lit. "hand wiper")

- A rectangular piece of fabric, usually cotton or linen, used for a variety of purposes, such as a handkerchief, hand towel and headscarf. tenugui come in a number of colours and patterns, and are also used as accessories in traditional Japanese dance and in kabuki.

- Waraji (草鞋)

- Traditional sandals woven from rope, designed to wrap securely around the foot and around the ankle; mostly worn by monks, and previously common footwear for the working classes.

- Yumoji (湯文字)

- A traditional kimono undergarment; a simple wrap-around skirt, worn with a susoyoke.

- Zōri (草履)

- Traditional sandals worn by both men and women, similar in design to flip-flops. Their formality ranges from strictly informal to fully formal. They are made of many materials, including cloth, leather, vinyl and woven bamboo, and can be highly decorated or very simple.

Women's straw zōri

Women's straw zōri

Layering

Pre-WW2, kimono were commonly worn layered, with three being the standard number of layers worn over the top of undergarments. The layered kimono underneath were known as dōnuki, and were often a patchwork of older or unwearable kimono taken apart for their fabric.

In modern-day Japan, layered kimono are only seen on the stage, whether for classical dances or in kabuki. A false second layer called a hiyoku ("second wing", 比翼) may be attached instead of an entirely separate kimono to achieve this look; it is a type of floating lining, sewn to the kimono only along the centre back and underneath the collar.

This effect allows it to show at the collar and the hem, and in some kabuki performances such as Fuji Musume, the kimono is worn with the okumi flipped back slightly underneath the obi to expose the design on the hiyoku. The hiyoku can also be seen on some bridal kimono.

Care

In the past, a kimono would often be entirely taken apart for washing, and then re-sewn for wearing.[21] This traditional washing method is called arai hari. Because the stitches must be taken out for washing, traditional kimono need to be hand sewn. Arai hari is very expensive and difficult and is one of the causes of the declining popularity of kimono. Modern fabrics and cleaning methods have been developed that eliminate this need, although the traditional washing of kimono is still practiced, especially for high-end garments.

New, custom-made kimono are generally delivered to a customer with long, loose basting stitches placed around the outside edges. These stitches are called shitsuke ito. They are sometimes replaced for storage. They help to prevent bunching, folding and wrinkling, and keep the kimono's layers in alignment.

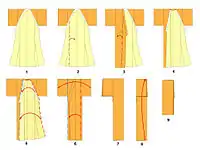

Like many other traditional Japanese garments, there are specific ways to fold kimono. These methods help to preserve the garment and to keep it from creasing when stored. Kimono are often stored wrapped in paper called tatōshi.

Kimono need to be aired out at least seasonally and before and after each time they are worn. Many people prefer to have their kimono dry cleaned. Although this can be extremely expensive, it is generally less expensive than arai hari but may be impossible for certain fabrics or dyes.

Notes

- Video reference showing Atami geisha Kyouma being dressed in hikizuri – the second video shows the difference between ohashori length at the front and back, showing how it is tied into the obi so as to be not visible.[35]

References

- Dalby, Liza (1993). Kimono: Fashioning Culture (1st ed.). Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780099428992.

- Spacey, John. "5 Embarrassing Kimono Mistakes". japan-talk.com. Japan Talk. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "About the size of tanmono (a roll of kimono cloth)". hirotatsumugi.jp. Hirota Tsumugi. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Sharnoff, Lora (1993). Grand Sumo: The Living Sport and Tradition. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0283-X.

- Liddell, Jill (1989). The Story of the Kimono. E.P. Dutton. p. 28. ISBN 978-0525245742.

- Fassbender, Bardo; Peters, Anne; Peter, Simone; Högger, Daniel (2012). The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 477. ISBN 978-0198725220.

- Elizabeth LaCouture, Journal of Design History, Vol. 30, Issue 3, 1 September 2017, Pages 300–314.

- Wada, Yoshiko Iwamoto; Rice, Mary Kellogg; Barton, Jane (2011). Shibori: The Inventive Art of Japanese Shaped Resist Dyeing (3rd ed.). New York: Kodansha USA, Inc. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-1-56836-396-7.

- 平安時代の貴族の服装 NHK for school

- 町人のきもの 1 寛文~江戸中期までの着物 Mami Baba. Sen'i gakkaishi vol.64

- 更新日:2010年11月25日. "戦時衣生活簡素化実施要綱". Ndl.go.jp. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Dees, Jan (2009). Taisho Kimono: Speaking of Past and Present (1st ed.). Milano, Italy: Skira Editore S.p.A. ISBN 978-88-572-0011-8.

- Ruddick, Graham (12 August 2014). "Rise of the kimono, the Japanese fashion taking Britain by storm". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Butler, Sarah; Moulds, Josephine; Cochrane, Lauren (12 August 2014). "Kimonos on a roll as high street sees broad appeal of Japanese garment". Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Ho, Vivian (1 July 2019). "#KimOhNo: Kim Kardashian West renames Kimono brand amid outcry". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Valk, Julie (2018). "Survival or Success? The Kimono Retail Industry in Contemporary Japan" (D.Phil thesis). University of Oxford. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Daijisen Dictionary. Shogakukan.

"呉服 Gofuku, Kure-hatori" 1. A general term for kimono textiles, a bolt of fabric 2. The name of silk fabrics as opposed to Futomono 3. A twill woven with the method from the country of Go in ancient China, Kurehatori (literally translates as a weave of Kure)

- Tanaka, Atsuko (2012). きもの自分流入門 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. p. 82. ISBN 9784093108041.

- Cliffe, Sheila (23 March 2017). The Social Life of Kimono (1st ed.). New York: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4725-8553-0.

- Wada, Ichiro; Wada, Yuka. ""Sakiori in Nishinomiya" Technique detail". tourjartisan.com. Tour J Artisan; Ichiroya. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Dalby, Liza (2000). Geisha (3rd ed.). London: Vintage Random House. ISBN 978-0099286387.

- Marshall, Linda. "Japanese Paste-Resist Dyeing · Katazome". washarts.com. Washi Arts - Exceptional Japanese Papers. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Miyoshi, Yurika. "季節の着物". kimono5.jp (in Japanese). スリーネクスト (株). Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "Kimono Seasonal Motifs, Colors and Flowers: Finished!". thekimonolady.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "男のきもの大全". Kimono-taizen.com. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Kimono Seasonal Motifs, Flowers, and Colors: May". thekimonolady.blogspot.com. 13 April 2013. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Costume History in Japan - The Kamakura Period". iz2.or.jp. The Costume Museum. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Watson, William, ed. (1981). The Great Japan Exhibition: Art of the Edo Period 1600-1868. London: Royal Academy of Arts. pp. 222–229.

[A number of visual examples of Edo-period kosode, with a variety of sleeve lengths and proportions showing the variation in style and shape throughout the era.]

- Coline, Youandi. "Women's vs Men's kimono". chayatsujikimono.wordpress.com. Chayatsuji Kimono. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Hindell, Juliet (22 May 1999). "Saving the kimono". BBC News. BBC News World. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Tsuruoka, Hiroyuki. "The unspoiled market found by the lost office workers". Japan Business Press (in Japanese). Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- "Mon and Kamon". wafuku.co.uk. Wafuku.co.uk. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Coline, Youandi. "Formality Series: Tsukesage". chayatsujikimono.wordpress.com. Chayatsuji Kimono. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Coline, Youandi. "Are kimono and hikizuri the same?". Chayatsuji Kimono. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- "[Video from Atami Geigi Kenban on Instagram]" (in Japanese). 11 December 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Kimino, Rinko; Somegoro, Ichikawa (2016). Photographic Kabuki Kaleidoscope (1st ed.). Tokyo: Shogakukan. p. 34. ISBN 978-4-09-310843-0.

- Yoshie, Fuami (26 March 2008). "Japanese Traditional Wedding Style: Shiromuku for Brides". Japanese Mind ―日本の心―. fyoshie060861.blogspot.com. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Coline, Youandi (5 December 2018). "Datejime". Chayatsuji Kimono. chayatsujikimono.wordpress.com. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Yamanaka, Norio (1982). The Book of Kimono. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International, p. 60. ISBN 0-87011-500-6 (USA), ISBN 4-7700-0986-0 (Japan).

- Underwear (Hadagi): Hada-Juban. KIDORAKU Japan. Accessed 22 October 2009.

- Yamanaka, Norio (1982). The Book of Kimono. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International, p. 76. ISBN 0-87011-500-6 (USA), ISBN 4-7700-0986-0 (Japan).

- Underwear (Hadagi): Kimono Slip. KIDORAKU Japan. Accessed 22 October 2009.

- Yamanaka, Norio (1982). The Book of Kimono. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International, p. 61. ISBN 0-87011-500-6 (USA), ISBN 4-7700-0986-0 (Japan).

- Nagajuban Archived 2008-08-30 at the Wayback Machine undergarment for Japanese kimono

- Imperatore, Cheryl, & MacLardy, Paul (2001). Kimono Vanishing Tradition: Japanese Textiles of the 20th Century. Atglen, Penn.: Schiffer Publishing. Chap. 3 "Nagajuban—Undergarments", pp. 32–46. ISBN 0-7643-1228-6. OCLC 44868854.

- Underwear (Hadagi): Susoyoke. KIDORAKU Japan. Accessed 22 October 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to kimono. |

| Look up kimono in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kimono buying guide. |

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization - Archive of the exhibition "The Landscape Kimonos of Itchiku Kubota"

- The Kyoto Costume Museum - Costume History in Japan

- Archived link to the Immortal Geisha Forums; comprehensive resource on kimono knowledge and culture

- Articles on kimono from the V&A Collection