Karoo

The Karoo (/kəˈruː/ kə-ROO; from the !Orakobab word ǃ’Aukarob "Hardveld"[2][3]) is a semi-desert natural region of South Africa. No exact definition of what constitutes the Karoo is available, so its extent is also not precisely defined. The Karoo is partly defined by its topography, geology and climate, and above all, its low rainfall, arid air, cloudless skies, and extremes of heat and cold.[4][5] The Karoo also hosted a well-preserved ecosystem hundreds of million years ago which is now represented by many fossils.[6]

Karoo

ǃ’Aukarob | |

|---|---|

Natural region | |

Typical Karoo vegetation to the south of Matjiesfontein, with the Anysberg Mountains visible in the background | |

Extent of the Karoo (olive-green) and Little Karoo (bright green) in South Africa, with the names of surrounding areas in blue. The thick interrupted line indicates the course of the Great Escarpment which delimits the Central South African Plateau. To the immediate south and south-west the solid lines trace the parallel ranges of the Cape Fold Belt.[1] | |

| Country | South Africa |

The ǃ’Aukarob formed an almost impenetrable barrier to the interior from Cape Town, and the early adventurers, explorers, hunters, and travelers on the way to the Highveld unanimously denounced it as a frightening place of great heat, great frosts, great floods, and great droughts.[7] Today, it is still a place of great heat and frosts, and an annual rainfall of between 50 and 250 mm, though on some of the mountains it can be 250 to 500 mm higher than on the plains.[4] However, underground water is found throughout the Karoo, which can be tapped by boreholes, making permanent settlements and sheep farming possible.[4][5]

The xerophytic vegetation consists of aloes, mesembryanthemums, crassulas, euphorbias, stapelias, and desert ephemerals, spaced 50 cm or more apart,[4][8] and becoming very sparse going northwards into Bushmanland and, from there, into the Kalahari Desert. The driest region of the Karoo, however, is its southwestern corner, between the Great Escarpment and the Cederberg-Skurweberg mountain ranges, called the Tankwa Karoo, which receives only 75 mm of rain annually.[4] The eastern and north-eastern Karoo are often covered by large patches of grassland. The typical Karoo vegetation used to support large game, sometimes in vast herds.[7][9]

Today, sheep thrive on the xerophytes, though each sheep requires about 4 ha of grazing to sustain itself.[4]

Divisions

The Karoo is distinctively divided into the Great Karoo and the Little Karoo by the Swartberg Mountain Range, which runs east-west, parallel to the southern coastline, but is separated from the sea by another east-west range called the Outeniqua–Langeberg Mountains. The Great Karoo lies to the north of the Swartberg range; the Little Karoo is to the south of it.

Great Karoo

The only sharp and definite boundary of the Great Karoo is formed by the most inland ranges of Cape Fold Mountains to the south and south-west. The extent of the Karoo to the north is vague, fading gradually and almost imperceptibly into the increasingly arid Bushmanland towards the north-west. To the north and north-east, it fades into the savannah and grasslands of Griqualand West and the Highveld.[1][11] The boundary to the east grades into the grasslands of the Eastern Midlands.[12] The Great Karoo is itself divided by the Great Escarpment into the Upper Karoo (generally above 1200–1500 m) and the Lower Karoo on the plains below at 700–800 m. A great many local names, each denoting different subregions of the Great Karoo, exist, some more widely, or more generally, known than others. In the Lower Karoo, going from west to east, they are the Tankwa Karoo, the Moordenaarskaroo, the Koup, the Vlakte, and the Camdeboo Plains. The Hantam, Kareeberge, Roggeveld, and uweveldare the better known subregions of the Upper Karoo, though most of it is simply known as the Upper Karoo, especially in the north.[1]

Little Karoo

The Little Karoo’s boundaries are sharply defined by mountain ranges to the west, north, and south. The road between Uniondale and Willowmore is considered, by convention, to form the approximate arbitrary eastern extremity of the Little Karoo. Its extent is much smaller than that of the Great Karoo.[1] Locally, it is usually called the Klein Karoo, which is Afrikaans for Little Karoo.

Geography

Great Karoo

The Great Karoo straddles the 30° S parallel on the west of the continent, in a similar position to other semidesert areas on earth, north and south of the equator. It is furthermore in the rainfall shadow of the Cape Fold Mountains along the western coastline.[1] The western "Lower Karoo" (the Tankwa Karoo and Moordenaarskaroo) contain remnants of the Cape Fold Mountains[13] (e.g. the Witteberg and Anysberg Mountains)[1] which give it a moderate hilly appearance, but further east, the Lower Karoo becomes a monotonously flat plain. The "Upper Karoo" has been intruded by dolerite sills (see below),[14] creating multiple flat-topped hills, or Karoo Koppies, which are iconic of the Great Karoo.

The vegetation of the Upper is similar to the Lower Karoo, so few people make a distinction between the two.

The main highway (the N1) and railway line from Cape Town to the north enter the Lower Karoo from the Hex River Valley just before Touws River and follow a course about 50 km south of the Great Escarpment up to Beaufort West. Thereafter, they gradually ascend the Great Escarpment along a broad valley to Three Sisters on the Central Plateau and the Upper Karoo.

Turning north from the N1 between Touws River and Beaufort West, at Matjiesfontein, the road ascends the Great Escarpment through the Verlatenkloof Pass to reach Sutherland, at 1456 m above sea level, which is reputedly the coldest town in South Africa with average minimum temperatures of −6.1 °C during winter.[15] Parts of the eastern Mpumalangan Highveld do at times experience lower temperatures than Sutherland, but not as consistently as Sutherland does.[15] Snowfalls are not infrequent during the southern winter months. The South African Astronomical Observatory has an emplacement of telescopes about 20 km east of the town, on a small plateau 1798 m above sea level, and is home to the Southern African Large Telescope, the largest optical telescope in the Southern Hemisphere.[16][17] To the north, still on the Plateau, and 75 km north-west of Carnarvon, seven radio dishes form part of the Square Kilometer Array which will, 2500 in total, be scattered in other parts of South Africa and Australia, to survey the southern skies at radio frequencies. Our galaxy, the Milky Way, one of the main targets of this enterprise, is best viewed from the Southern Hemisphere.[18] The Upper Karoo is indeed an ideal site for an astronomical observatory. This is not only because of the clear skies, absence of artificial lights, and high altitude, but also because it is tectonically completely inactive (meaning that there are no fault lines or volcanoes nearby,[13] and no earth tremors or earthquakes occur, even at great distances).[19]

Little Karoo

The Little Karoo is separated from the Great Karoo by the Swartberg Mountain range. Geographically, it is a 290-km-long valley, only 40–60 km wide, formed by two parallel Cape Fold Mountain ranges, the Swartberg to the north, and the continuous Langeberg-Outeniqua range to the south. The northern strip of the valley, within 10–20 km from the foot of the Swartberg mountains is least karoo-like, in that it is a well-watered area both from the rain and the many streams that cascade down the mountain, or through narrow defiles in the Swartberg from the Great Karoo. The main towns of the region are situated along this northern strip of the Little Karoo: Montagu, Barrydale, Ladismith, Calitzdorp, Oudtshoorn, and De Rust, as well as such well-known mission stations such as Zoar, Amalienstein, and Dysselsdorp.

The southern 30– to 50-km-wide strip, north of the Langeberg range, is as arid as the western Lower Karoo, except in the east, where the Langeberg range (arbitrarily) starts to be called the Outeniqua Mountains.

The Little Karoo can only be accessed by road through the narrow defiles cut through the surrounding Cape Fold Mountains by ancient, but still flowing, rivers. A few roads traverse the mountains over passes, the most famous and impressive of which is the Swartberg Pass between Oudtshoorn in the Little Karoo and Prince Albert on the other side of the Swartberg mountains in the Great Karoo. Also, the main road between Oudtshoorn and George, on the coastal plain, crosses the mountains to the south via the Outeniqua Pass. The only exit from the Little Karoo that does not involve crossing a mountain range is through the 150-km-long, narrow Langkloof valley between Uniondale and Humansdorp, near Plettenberg Bay.

Geology of the Karoo

The Great Karoo

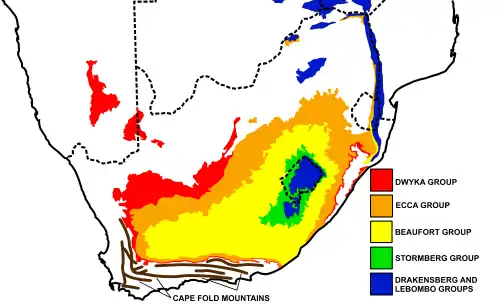

In geological terms, the Karoo Supergroup refers to an extensive and geologically recent (180–310 million years old) sequence of sedimentary and igneous rocks,[14] which is flanked to the south by the Cape Fold Mountains, and to the north by the more ancient Ventersdorp Lavas, the Transvaal Supergroup and Waterberg Supergroup.[13] It covers two-thirds of South Africa and extends in places to 8000 m below the land surface, constituting an immense volume of rocks which was formed, geologically speaking, in a short period of time.[20][21] Although almost the whole of the Great Karoo is situated on Karoo Supergroup rocks, the geological Karoo rocks extend over a very much larger area, both within South Africa and Lesotho, but also beyond its borders and onto other continents that formed part of Gondwana.[5][13][14]

Geological history of the Karoo Supergroup

The Karoo Supergroup was formed in a vast inland basin starting 320 million years ago, at a time when that part of Gondwana which would eventually become Africa, lay over the South Pole.[11][22] Icebergs that had calved off the glaciers and ice sheets to the north deposited a 1-km-thick layer of mud containing dropstones of varying origins and sizes into this basin. This became the Dwyka Group consisting primarily of tillite, the lowermost layer of the Karoo Supergroup.[14] As Gondwana drifted northwards, the basin turned into an inland sea with extensive swampy deltas along its northern shores. The peat in these swamps eventually turned into large deposits of coal which are mined in KwaZulu-Natal and on the Highveld. This 3-km-thick layer is known as the Ecca Group, which is overlain by the 5.6-km-thick Beaufort Group, laid down on a vast plain with Mississippi-like rivers depositing mud from an immense range of mountains to the south.[14] Ancient reptiles and amphibians prospered in the wet forests, and their remains have made the Karoo famous amongst palaeontologists. The first of these Karoo fossils was discovered in 1838 by Scots-born Andrew Geddes Bain at a road cutting near Fort Beaufort. He sent his specimens to the British Museum, where fellow Scotsman Robert Broom recognised the Karoo fossils' mammal-like characteristics in 1897.[23]

After the Beaufort period, Southern Africa (still part of Gondwana) became an arid sand desert with only ephemeral rivers and pans. These sands consolidated to form the Stormberg Group, the remnants of which are found only in the immediate vicinity of Lesotho. Several dinosaur nests, containing eggs, some with dinosaur fetal skeletons in them, have been found in these rocks, near what had once been a swampy pan.[24][25][26]

Finally, about 180 million years ago, volcanic activity took place on a titanic scale, which brought an end to a flourishing reptile evolution.[23] These genera represent some of the extinct, mainly predinosaur, animals of the Karoo:

Karoo Koppies hills are capped by hard, erosion-resistant dolerite sills. This is solidified lava that was forced under high pressure between the horizontal strata of the sedimentary rocks that make up most of the Karoo’s geology. This occurred about 180 million years ago, when huge volumes of lava were extruded over most of Southern Africa and adjoining regions of Gondwana, both on the surface and deep below the surface between the sedimentary strata. Since this massive extrusion of lava, Southern Africa has undergone a prolonged period of erosion, exposing the older, softer rocks, except where they were protected by a cap of dolerite. The genera present include:

- Mesosaurus, aquatic Dwyka carnivore

- Bradysaurus, Beaufort Group herbivore

- Diictodon, Permian synapsid

- Rubidgea, Permian predator

- Lystrosaurus, Triassic herbivorous therapsid

- Thrinaxodon, Triassic carnivorous therapsid

- Euparkeria, archosaur

- Massospondylus, late Triassic to early Jurassic herbivorous, bipedal dinosaur

- Megazostrodon, early mammal[23]

The lava outpourings that ended the Karoo deposition of rocks, not only covered the African surface, and other parts of Gondwana with a 1.6 km thick layer basaltic lava,[14] but it also forced its way, under high pressure, between the horizontal layers of sedimentary rocks belonging to the Ecca and Beaufort groups, to solidify into dolerite sills. The long vertical fissures through which the lava welled up solidified into dikes which resemble the Great Wall of China from the air.[5] From about 150 million years ago the South African surface has been subjected to an almost uninterrupted period of erosion, particularly during the past 20 million years,[14] shaving off many kilometers of sediments. This exposed the dolerite sills, which were more resistant to erosion than the Karoo sediments, forming one of the most characteristic features of the Karoo landscape, namely the flat topped hills, called "Karoo Koppies".

Geology of the Little Karoo

The geology of the Little Karoo bears no resemblance to that of the Great Karoo (see the diagram on the left, of a NS geological cross-section through the Little and Great Karoos).[11] The valley is an integral part of the Cape Fold Mountain Belt, with the two ranges on either side composed of extremely hard, erosion-resistant, quartzitic sandstone belonging to the 450- to 510-million-year-old Table Mountain Group (i.e. the oldest layer of the Cape Supergroup). The valley floor is covered, in the main, by the next (younger) layer of the Supergroup, namely the much softer Bokkeveld shales. The dolerite of the Great Karoo did not penetrate these rocks, so Karoo Koppies are not seen in the Little Karoo.[13]

The Little Karoo contains two other geological features that give the landscape a special character. During the erosion of the African interior following the bulging of the continent during the massive lava outpourings that ended the Karoo sedimentation 180 million years ago, some of the eroded material was trapped in the valleys of the Cape Fold Mountains, especially during the Cretaceous period, about 145 ± 4 to 66 million years (Ma) ago. These "Enon Conglomerates", as they are known, were deposited by high energy, fast flowing rivers,[14] and are found between Calitzdorp and Oudtshoorn, where they form the strikingly red "Redstone Hills".[1][11][13][15][27]

The second special geological feature that marks the Little Karoo is the 300-km-long fault line along the southern edge of the Swartberg Mountains. The Swartberg Mountains were lifted up along this fault, to such an extent that in the Oudtshoorn region, the rocks that form the base of the Cape Supergroup are exposed. These are locally known as the Cango Group, but are probably continuous with the Malmesbury Group that forms the base of Table Mountain on the Cape Peninsula, and similar outcrops in the Western Cape.[14] In the Little Karoo, the outcrop is composed of limestone, into which an underground stream has carved the impressively extensive Cango Caves.[5][11][13][15]

Karoo flora

The World Wildlife Fund has classified the Great Karoo and Little Karoo as almost entirely within two of what they consider South Africa’s eight botanical biomes,[28] they have coined their biomes succulent Karoo and the Nama Karoo, although both, like the geological Karoo Supergroup, are more extensive than the geographical or historical Karoo described in South African atlases and guide books (compare the map on the right with the map at the beginning of the article).[5][15][29]

Succulent Karoo biome

The succulent Karoo biome runs along the West Coast, from approximately Lamberts Bay northwards to over 200 km into southern Namibia.[30][31] It starts in the south just north of the sandveld geographical region, about 250 km north of Cape Town, and continues through Namaqualand, the Richtersveld, immediately south of the Orange River, and on into the Namaqualand or Namaland region of southern Namibia. None of these regions is ever referred to, either geographically or locally, as "Karoo".[11] However, it has a major extension inland into the Tankwa Karoo and Moordenaarskaroo regions of the Lower Karoo, and adjoining Upper Karoo region of the geographic Great Karoo. It also occurs to the south, in part of the Breede River Valley, as the Robertson Karoo. From here, it continues eastwards into the western half of the Little Karoo.[1][4][5][11][15][29]

The succulent Karoo biome is dominated by dwarf, leafy-succulent shrubs, and annuals, predominantly Asteraceae, popularly known as Namaqualand daisies, which put on spectacular flower displays covering vast stretches of the landscape in the southern spring-time (August–September) after good rains in the winter. Grasses are uncommon, making most of the biome unsuitable for grazing. The low rainfall, in fact, discourages most forms of agriculture. An exception is the thriving ostrich-farming industry in the Little Karoo, which is heavily dependent on supplementary feeding with lucerne.[5][15] The difference between the succulent Karoo biome and the Nama Karoo biome is that the former receives the little rain that falls as cyclonic rainfall in winter, which has less erosive power than the infrequent but violent summer thunderstorms of the Nama Karoo.[30] Frost is also less common in the succulent Karoo biome than in the Nama Karoo biome.[30] The number of mainly succulent plant species is very high for an arid area of this size anywhere in the world.[30]

Nama Karoo biome

The Nama Karoo biome is located entirely on the central plateau mostly at altitudes between 1000 and 1500 m.[32][33] It incorporates nearly the whole of the historical and geographical Great Karoo, but also includes a portion of southern Namibia's Namaqualand, and South Africa's Bushmanland (both local geographical names, not names of biomes).[1][11] It is the second-largest biome in South Africa,[32][33] and forms the botanical transition between the fynbos biome[34] to the south and the savannah biome[35] to the north. It is defined primarily by the dominance of dwarf (less than 1 m high) shrubs with a co-dominance of grasses especially towards the north-east and east where it grades into the grassland biome of the highveld and the Eastern Midlands.[36] The shrubs and grasses are deciduous, mainly in response to the irregular rainfall.[32][33] Much of the Nama Karoo biome is used for sheep and goat farming, providing mutton, wool, and pelts for local and international markets, especially since livestock can frequently be provided with a regular supply of water from boreholes. Overgrazing exacerbates the erosion caused by the violent thunderstorms that occur, infrequently, in the summer. It also promotes the replacement of the grasses by shrubs, especially the less edible varieties such as the threethorn (Rhigozum trichotomum), bitterbos (Chrysocoma ciliata), and sweet thorn (Acacia karroo).[32][33] However, there are few rare or Red Data Book plant species in the Nama Karoo biome.[32][33]

Karoo fauna

Great Karoo

The Great Karoo used to support a large variety of antelope (particularly the springbok), the quagga, and other large game, especially on the grassy flats in the east. Francois Le Vaillant, the famous French explorer, naturalist, and ornithologist, who traveled through the Great Karoo in the 1780s, killed a hippopotamus in the Great Fish River in the Karoo (and ate its foot for breakfast). He also recorded that he saw the spoor of a rhinoceros near Cranemere, in the Camdeboo Plains (eastern Lower Karoo). Elephant tusks have been found by farmers in the Camdeboo district, but no records exist of any having been seen alive in that region.[7] The quagga roamed the Karoo in great numbers together with wildebeest and ostriches, which always seemed to accompany them.[7] These quagga seemed gentle and easy to domesticate. (A pair of quagga was used to draw a horse carriage through London, more for curiosity than for any superiority the quagga might have had over a horse.) They were consequently also easy prey for hunters, who hunted them for sport rather than their meat.[7] By the middle of the 1800s, they were almost extinct, and in 1883, the last one died in an Amsterdam zoo.

Probably the strangest and most puzzling zoological phenomenon in the Great Karoo was the periodic, unpredictable appearance of massive springbok migrations.[7][9] These migrations always came from the north, and could either go west towards Namaqualand and the sea, south-west through towns such as Beaufort West, or south through the Camdeboo district. These vast herds moved steadily and inexorably across the plains, trampling all before them, including their own kind. Le Vaillant gave the first eyewitness account of such a migration in 1782.[7] He rode through the herd filling the Plains of Camdeboo, seeing neither the beginning nor end of the moving mass.

In 1849, a massive herd of springbok, amongst which were intermingled wildebeest, blesbok, quagga, and eland, moved through Beaufort West. Early one morning, the town was awakened to a sound like that of a strong wind, and suddenly the town was filled with animals. They devoured every sprig of foliage in the town and surrounding countryside. The last of the continuously moving herd left the town 3 days later, to disappear towards the west. The Karoo looked as if a fire had swept through it. During these migrations, the plains and hillsides on every side were thickly covered by one vast mass of springbok, packed like sheep in a fold. As far as the eye could see, the landscape was alive with them.[7]

During these migrations, the springbok never ran or trotted. On the whole, they were silent, except for the shudder of their stamping hoofs. Nothing could divert them, and hunters could ride amongst them, shooting them at random, without apparently causing alarm. People could move amongst them and kill them with sticks, or cripple them by seizing a leg and breaking it. Not only people followed these herds for the easy meat they provided, but also lions, leopards, cheetahs, African wild dogs, hyenas, and jackals preyed on them.[7]

No one knew how, why, or where these migrations started, nor where they ended, nor did anyone know if these animals ever returned to where they had started. The migrations were always unidirectional, from north of the Great Karoo.[7]

Great locust swarms also frequently invaded or arose in the Great Karoo, and still occur from time to time today.[7]

The riverine rabbit, a critically endangered animal, lives exclusively in seasonal river basins and a very particular set of scrubland in the central semiarid region in the Karoo.[37] It is hunted by falconiformes and Verreaux's eagles.[38] Its numbers have been consistently lowering due to destruction of its habitat.[39] They are unique relative to similar species through how they are polygamous and how each female can only produce one or two offspring per year.[38]

The introduction of the windpump to tap the Great Karoo’s underground water resources in the late 1800s made permanent human habitation and sheep farming possible over large parts of the Great Karoo for the first time.[5][15] As a result, the teeming number of large antelope in the Karoo has dwindled into insignificance, and with them, the large carnivores have all but disappeared. Today, the caracal (7–19 kg),[40] black-backed jackal (6–10 kg),[40] Verreaux's eagle (3.0–5.8 kg) and the martial eagle (3.0–6.2 kg)[41][42] are arguably the largest predators likely to be seen in the Great Karoo today. Leopards (20–90 kg) do occur, especially in the mountains, but are very secretive, so are rarely seen.[40] Many of the animals that formerly inhabited the Karoo in large numbers, including lions, have been reintroduced to the area in nature reserves and game farms.

Little Karoo

As in the Great Karoo, antelope and other big game inhabited the Little Karoo in the past. However, the dominant zebra was not the quagga, but the Cape mountain zebra, (Equus zebra zebra) which is adapted for life on rugged, mountainous terrain. Their hooves are harder and faster-growing than those of Burchell’s zebra (Equus quagga burchellii), which lives on the plains.[43] The two species are, therefore, rarely seen in the same habitat. The quagga is closely related to Burchell's zebra, and appears also to have been confined to the plains.

The mountain zebra occurred in the mountain regions of the Cape Fold Belt and along the southern portion of the Great Escarpment. Thus, they were endemic to, amongst others, the western Lower Karoo and the Little Karoo. However, they were hunted to near extinction, leaving fewer than 100 individuals by the 1930s. Conservation efforts since then brought their numbers up to 1200 by 1998, mainly by concentrating these zebra in nature reserves and protected areas, the most well-known of these being the Mountain Zebra National Park near Cradock in the Great Karoo. Cape mountain zebras are still found in protected areas managed by Cape Nature, including the Kamanassie and Gamkaberg Nature Reserves.

The ostrich is found throughout Africa, but the most handsome specimens came from the Little Karoo, where the dry weather, but plentiful water in the streams formed an ideal habitat for these large, flightless birds. Here, they grow to over 2 m in height, and weigh over 100 kg. The male’s feathers have been prized by many cultures in Africa, Europe, and Asia over thousands of years.[5][15] In the 1860s, a farmer in the Graaff-Reinet district was apparently the first person to demonstrate that the ostrich could successfully be domesticated, bred in captivity, and the eggs hatched in incubators, while still producing the magnificent feathers.[15] This idea was quickly adopted by farmers in the Little Karoo, where they started growing lucerne as the birds' favorite food. During 1880, no less than 74,000 kg of feathers were exported, and in 1904, it passed the 210,000-kg mark.[15]

The First World War brought about a slump in the ostrich feather market, but the industry recovered in later years, when not only the feathers were sought after, but also ostrich leather, and its meat, which is very tasty, and a major export item. Today, several farms can be visited by tourists, near Oudtshoorn, the center of the ostrich industry.[5][15]

Modern history

Great Karoo

The first European settlers landed in the Cape of Good Hope in 1652, and between 1659 and 1664, made several unsuccessful attempts to penetrate the Great Karoo from the south-west.[4] The Europeans who first entered the Great Karoo did so from the south-east (traveling north from Algoa Bay), which is slightly less arid than the western Karoo.[7][15] These were the trekboers of the mid-1700s, who led a nomadic existence, enduring great hardships in the relentless aridity, the intense heat (such that even their dogs could not walk on the scorching ground and had to be lifted into the overcrowded wagons), and the bitter cold in winter, especially at night.[7] Before that time, the only inhabitants were the Khoe-speaking clans migrating through the area, and !Ui-speaking peoples, who lived in small family groups and, it is believed, remained largely in their own "territories", killing their own game, and gathering bulbs and roots and drinking from a spring or other water source within their territory.[7][15] Sometimes these territories were very large and the family group moved from one part to the other. Their only domestic animals were dogs.[7] The Ntu-speaking agriculturalists to the east of the Great Karoo did not occupy this arid region due to the scarce rainfall which prevented the farming of cattle.

In 1854, Daniel Halladay invented the multibladed windpump (windmill) in the USA. It was perfected in 1883, and soon South Africa (and elsewhere) produced them in large numbers. These windpumps transformed the Great Karoo, making permanent settlement and stock farming (predominantly sheep)[5] possible over large parts of the Karoo for the first time.[15] Like the Karoo Koppie, the multibladed windpump became an iconic feature of the Great Karoo. Sheep farming and the fencing off of the land have meant that antelope numbers have dwindled significantly, and with them, the big carnivores. Leopards still occur in the mountains, but lions now only occur in nature reserves, where they have been recently reintroduced into the Great Karoo.

In 1872, construction was started to connect the Cape Colony's coastal railway system with the diamond fields in Kimberley,[44][45] The new line started in Worcester and entered the Lower Karoo through the Hex River valley, where it followed a course almost midway between the Swartberg Mountains to the south and the Great Escarpment to the north. Along the way, it passed through the quaint Victorian village of Matjiesfontein, with the historic Lord Milner Hotel, which is still operational today. The railway reached this point in 1878, before proceeding to Beaufort West at the foot of the Great Escarpment. From there, it reached the top of the African Plateau near Three Sisters along a valley with such a low gradient that passengers were (and still are) hardly aware that they were ascending the Great Escarpment. From there it continued through the Upper Karoo, to De Aar, and crossed the Orange River at Hopetown, where South Africa’s first diamond, the Eureka Diamond, was found. The Orange River, at this point, forms the local unofficial boundary between the Great Karoo and the Highveld.[5]

The line reached Kimberley in 1885, and has since been extended via Botswana (then Bechuanaland) to reach Zimbabwe and Zambia (when they were still known as South and North Rhodesia), and branch lines have been constructed to Namibia and Port Elizabeth through a hub at De Aar, in the Great Karoo. Further branch lines were later built from points further north to Bloemfontein, Durban, and, of course, to Johannesburg.

During the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902, three Republican commando units, reinforced by the sympathizers ("rebels") from the Cape Colony, conducted widespread operations throughout the Karoo. Countless skirmishes took place in the region, with the Calvinia magisterial district, in particular, contributing a significant number of fighters to the Republican cause. Fought both conventionally and as a guerrilla struggle over the Karoo's vast expanses, it was a bloody war of attrition wherein both sides used newly developed technologies to their advantage. Numerous abandoned blockhouses can still be seen at strategic locations, especially along the railway line, throughout the Great Karoo. A prime example still "guards" a bridge over the Buffels River, 12 km (7.5 mi) to the east of the town of Laingsburg, in the Lower Karoo, between Matjiesfontein and Beaufort West.

Recently, nature reserves and game farms have been established in many parts of the Great Karoo, turning what was once regarded as a forbiddingly desolate and unattractive geographical barrier into a tourist destination.

Little Karoo

This area was explored by European settlers in the late 17th century, who encountered the Khoisan people as the original inhabitants of this area. The latter called the Swartberg Mountains kango meaning "a place rich in water".[5] The Cango Caves in the Swartberg Mountains are named after this Khoisan word.

The Little Karoo, and especially Oudtshoorn, became synonymous with the ostrich-feather industry in the 1880s.[5][15][27] The resulting "feather millionaires" built Victorian "Feather Palaces" all over town, using the red rocks belonging to the Enon Conglomerate, and related Kirkwood Formation, to build them.[11] These grand red palaces and other buildings in Oudtshoorn can still be admired today.

A railway line was built to connect Calitzdorp and Oudtshoorn, to Willowmore and from there, via Klipplaat, to Port Elizabeth, from where the ostrich feathers from the Little Karoo’s ostrich farms could be exported to Europe. That line is no longer in use today.

The Swartberg Pass was built, with convict labor, between 1881 and 1888 by Thomas Bain, son of the famous Andrew Geddes Bain, who built Bain's Kloof Pass and many others in the Western Cape. The main motivation for building the pass was to provide an all-weather road connection between the southern Great Karoo, and Oudtshoorn (and from there to the sea).[5][15] The two alternative roads, through the Meiringspoort and the Seweweekspoort defiles, were subject to periodic flooding, after heavy thunderstorms in the Great Karoo. The Swartberg Pass is not tarred and can be treacherously slippery after rain. It also becomes impassable after heavy snowfalls on the mountain, a not infrequent occurrence in winter.

Karoo in literature

Poet Thomas Hardy wrote of the Karoo in his 1899 poem "Drummer Hodge" (or "The Dead Drummer").[46]

Rudyard Kipling, in his 1901 poem "Bridge-Guard in the Karroo", evoked the loneliness experienced by blockhouse soldiers at Ketting station on the Dwyka River while guarding the Karoo railway track, a lifeline during the South African War.[47]

The Nuweveld Mountains near Beaufort West

The Nuweveld Mountains near Beaufort West The Lower Karoo

The Lower Karoo.jpg.webp) The Valley of Desolation near Graaff-Reinet

The Valley of Desolation near Graaff-Reinet Typical Karoo koppies near Cradock

Typical Karoo koppies near Cradock

See also

References

- Atlas of Southern Africa. (1984). p. 13, 98–106, 114–119. Reader’s Digest Association, Cape Town

- "karoo". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/file%20uploads%20/12_du_plessis_chapter_06_b.pdf

- Potgieter, D.J. & du Plessis, T.C. (1972) Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Vol. 6. pp. 306–307. Nasou, Cape Town.

- Reader’s Digest Illustrated Guide to Southern Africa. (5th Ed. 1993). pp. 78–89. Reader’s Digest Association of South Africa Pty. Ltd., Cape Town.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- Palmer, E. (1966) The Plains of Camdeboo. p. 12-13, 120, 126, 140–146. Fontana/ Collins, London.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Micropaedia, Vol. 6. (2007). p. 750. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., Chicago.

- Conolly, D. (1992). Conolly’s Guide to Southern Africa. (5th Ed.) pp. 106–117. Conolly Publishers, Scottburgh.

- McCarthy, T.S. (2013) The Okavango delta and its place in the geomorphological evolution of Southern Africa. South African Journal of Geology 116: 1–54.

- Norman, N., Whitfield, G. (2006) Geological Journeys. p. 206-223, 243–247, 252–273, 300–311. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- Grassland biome. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Geological Map of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. (1970). Council for Geoscience, Geological Survey of South Africa.

- McCarthy, T., Rubridge, B. (2005). The Story of Earth and Life. p. 89-90, 102–107, 134–136,159–161, 195–211, 248–254. Struik Publishers, Cape Town

- Bulpin, T.V. (1992). Discovering Southern Africa. pp. 271–274, 301–314. Discovering Southern Africa Productions, Muizenberg.

- "Deep Space Observatories: The Southern African Large Telescope". Space Today Online. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- "273 Precision Actuators for the Largest Telescope in the Southern Hemisphere". Physik Instrumente (PI) GmbH & Co. KG. May 2003. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- The Great Karoo . Accessed 2014-04-24.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1975); Macropaedia, Vol. 17. p. 60. Helen Hemingway Benton Publishers, Chicago.

- Bulpin, Thomas Victor (1985). "7. The lost world of the dinosaurs: The Karoo sequence". Scenic Wonders of Southern Africa. Books of Africa. pp. 199–221. ISBN 0-949956-26-0.

- Reid, R. (ed.) (2005). "7. The lost world of the dinosaurs: The Karoo sequence". The Story of Earth & Life. Struik Publishers. pp. 199–221. ISBN 1-77007-148-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Jackson, A.A., Stone, P. (2008). Bedrock Geology UK South. p. 6-7. Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey.

- Walton, Christopher (ed.) (1984). "Anatomy of South Africa: 200 million years ago". Atlas of Southern Africa. The Reader's Digest Association South Africa. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-947-008-02-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Knight, Will (28 July 2005). "Early dinosaurs crawled before they ran". New Scientist. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- Footprint. "Rhebok Hiking Trail" (PDF). Retrieved 13 August 2006.

- Weishampel, David B; et al (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Early Jurassic, Africa)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 535–536. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Van Deventer, L. & McLennan, B. (eds) (2010). "The Little Karoo" in South Africa by Road, a Regional Guide. p. 58-61. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- Biomes of South Africa. Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 13 May 2014

- The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World. (1999) p. 90. Times Books Group, London.

- Succulent Karoo. Accessed 30 April 2014

- Succulent Karoo. . Accessed 30 April 2014

- The Nama Karoo Biome. . Accessed 2 May 2014

- The Nama Karoo Biome "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed 2 May 2014

- Fynbos Biome . Accessed 2 May 2014

- Savanna Biome "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed 2 May 2014

- Grassland Biome "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed 2 May 2014

- "Bunolagus monticularis riverine rabbit". Animal Diversity Web.

- "Bunolagus monticularis (Riverine rabbit)". Biodiversity Explorer.

- "Bunolagus monticularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Stuart, C. & Stuart, T (2007). Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa p. 136, 170, 176. Struik, Cape Town

- Hockey, P.A.R., Dean, W.R.J. & Ryan, P.G. (2005). Roberts Birds of Southern Africa. (7th Edition). p. 531, 497. Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town.

- Oberprieler, U. & Cillié, B. (2002) Raptor Identification Guide for Southern Africa. pp. 62, 82. Rollerbird Press, Pinegowrie.

- Moodley, Y. & Harley, E.H. (2006) Population structuring in mountain zebra (Equus zebra):the molecular consequences of divergent histories. Conservation Genetics. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9083-8

- Burman, Jose (1984). Early Railways at the Cape. Cape Town. Human & Rousseau, p. 95. ISBN 0-7981-1760-5

- Royal Colonial Society: Proceedings of the Royal Colonial Institute. Northumberland Avenue, London. 1898. p. 26. "The Railway System of South Africa".

- Thomas Hardy (1899). "The Dead Drummer".

- Mary Hamer. ""Bridge-Guard in the Karroo": Notes". Retrieved 22 April 2012. The poem was first published in The Times of 5 June 1901.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karoo. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Karroo. |

Karoo travel guide from Wikivoyage

Karoo travel guide from Wikivoyage- http://www.karoospace.co.za

- Karoo, South Africa

.jpg.webp)