Quagga

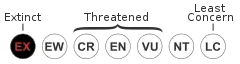

The quagga (/ˈkwɑːxɑː/ or /ˈkwæɡə/)[2][3][4] (Equus quagga quagga) was a subspecies of the plains zebra that lived in South Africa until hunted to extinction late in the 19th century by European settler-colonists. It was long thought to be a distinct species, but early genetic studies have supported it being a subspecies of plains zebra. A more recent study suggested that it was the southernmost cline or ecotype of the species. The name comes from the Khoekhoe language and is thought to be derived from its call, which sounded like "kwa-ha".[5]

| Quagga Temporal range: Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| A quagga mare at the London Zoo in 1870; this is the only specimen photographed alive | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †E. q. quagga |

| Trinomial name | |

| Equus quagga quagga (Boddaert, 1785) | |

| |

| Former range in red | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The quagga is believed to have been around 257 cm (8 ft 5 in) long and 125–135 cm (4 ft 1 in–4 ft 5 in) tall at the shoulder. It was distinguished from other zebras by its limited pattern of primarily brown and white stripes, mainly on the front part of the body. The rear was brown and without stripes, and appeared more horse-like. The distribution of stripes varied considerably between individuals. Little is known about the quagga's behaviour, but it may have gathered into herds of 30–50. Quaggas were said to be wild and lively, yet were also considered more docile than Burchell's zebra. They were once found in great numbers in the Karoo of Cape Province and the southern part of the Orange Free State in South Africa.

After the Dutch settlement of South Africa began, the quagga was extensively hunted, as it competed with domesticated animals for forage. Some were taken to zoos in Europe, but breeding programmes were unsuccessful. The last wild population lived in the Orange Free State; the quagga was extinct in the wild by 1878. The last captive specimen died in Amsterdam on 12 August 1883. Only one quagga was ever photographed alive, and only 23 skins are preserved today. In 1984, the quagga was the first extinct animal whose DNA was analysed. The Quagga Project is trying to recreate the phenotype of hair coat pattern and related characteristics by selectively breeding the closest subspecies which is Burchell's zebra.

Taxonomy

The name "quagga" is derived from the Khoikhoi word for zebra (cf Tshwa ||koaah "zebra"[6]) and is onomatopoeic, being said to resemble the quagga's call, variously transcribed as "kwa-ha-ha",[7] "kwahaah",[2] or "oug-ga".[8] The name is still used colloquially for the plains zebra.[7] The quagga was originally classified as a distinct species, Equus quagga, in 1778 by Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert.[9] Traditionally, the quagga and the other plains and mountain zebras were placed in the subgenus Hippotigris.[10]

Much debate has occurred over the status of the quagga in relation to the plains zebra. The British zoologist Reginald Innes Pocock in 1902 was perhaps the first to suggest that the quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra. As the quagga was scientifically described and named before the plains zebra, the trinomial name for the quagga becomes E. quagga quagga under this scheme, and the other subspecies of the plains zebra are placed under E. quagga, as well.[11]

Historically, quagga taxonomy was further complicated because the extinct southernmost population of Burchell's zebra (Equus quagga burchellii, formerly Equus burchellii burchellii) was thought to be a distinct subspecies (also sometimes thought a full species, E. burchellii). The extant northern population, the "Damara zebra", was later named Equus quagga antiquorum, which means that it is today also referred to as E. q. burchellii, after it was realised they were the same taxon. The extinct population was long thought very close to the quagga, since it also showed limited striping on its hind parts.[10] As an example of this, Shortridge placed the two in the now disused subgenus Quagga in 1934.[12] Most experts now suggest that the two subspecies represent two ends of a cline.[13]

Different subspecies of plains zebras were recognised as members of Equus quagga by early researchers, though much confusion existed over which species were valid.[14] Quagga subspecies were described on the basis of differences in striping patterns, but these differences were since attributed to individual variation within the same populations.[15] Some subspecies and even species, such as E. q. danielli and Hippotigris isabellinus, were based only on illustrations (iconotypes) of aberrant quagga specimens.[16][17] One craniometric study from 1980 seemed to confirm its affiliation with the horse (Equus ferus caballus), but early morphological studies have been noted as being erroneous. Studying skeletons from stuffed specimens can be problematical, as early taxidermists sometimes used donkey and horse skulls inside their mounts when the originals were unavailable.[18][13]

Evolution

The quagga is poorly represented in the fossil record, and the identification of these fossils is uncertain, as they were collected at a time when the name "quagga" referred to all zebras.[7] Fossil skulls of Equus mauritanicus from Algeria have been claimed to show affinities with the quagga and the plains zebra, but they may be too badly damaged to allow definite conclusions to be drawn from them.[11]

The quagga was the first extinct animal to have its DNA analysed,[19] and this 1984 study launched the field of ancient DNA analysis. It confirmed that the quagga was more closely related to zebras than to horses,[20] with the quagga and mountain zebra (Equus zebra) sharing an ancestor 3–4 million years ago.[19] An immunological study published the following year found the quagga to be closest to the plains zebra.[21] A 1987 study suggested that the mtDNA of the quagga diverged at a range of roughly 2% per million years, similar to other mammal species, and again confirmed the close relation to the plains zebra.[22]

Later morphological studies came to different conclusions. A 1999 analysis of cranial measurements found that the quagga was as different from the plains zebra as the latter is from the mountain zebra.[20] A 2004 study of skins and skulls instead suggested that the quagga was not a distinct species, but a subspecies of the plains zebra.[10] In spite of these findings, many authors subsequently kept the plains zebra and the quagga as separate species.[7]

A genetic study published in 2005 confirmed the subspecific status of the quagga. It showed that the quagga had little genetic diversity, and that it diverged from the other plains zebra subspecies only between 120,000 and 290,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene, and possibly the penultimate glacial maximum. Its distinct coat pattern perhaps evolved rapidly because of geographical isolation and/or adaptation to a drier environment. In addition, plains zebra subspecies tend to have less striping the further south they live, and the quagga was the most southern-living of them all. Other large African ungulates diverged into separate species and subspecies during this period, as well, probably because of the same climate shift.[20]

The simplified cladogram below is based on the 2005 analysis (some taxa shared haplotypes and could, therefore, not be differentiated):[20]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

A 2018 genetic study of plains zebras populations confirmed the quagga as a member of that species. They found no evidence for subspecific differentiation based on morphological differences between southern populations of zebras, including the quagga. Modern plains zebra populations may have originated from southern Africa, and the quagga appears to be less divergent from neighbouring populations than the northernmost living population in northeastern Uganda. Instead, the study supported a north–south genetic continuum for plains zebras, with the Ugandan population being the most distinct. Zebras from Namibia appear to be the closest genetically to the quagga.[23]

Description

The quagga is believed to have been 257 cm (8 ft 5 in) long and 125–135 cm (4 ft 1 in–4 ft 5 in) tall at the shoulder.[13] Based on measurements of skins, mares were significantly longer and slightly taller than stallions, whereas the stallions of extant zebras are the largest.[24] Its coat pattern was unique among equids: zebra-like in the front but more like a horse in the rear.[20] It had brown and white stripes on the head and neck, brown upper parts and a white belly, tail and legs. The stripes were boldest on the head and neck and became gradually fainter further down the body, blending with the reddish brown of the back and flanks, until disappearing along the back. It appears to have had a high degree of polymorphism, with some having almost no stripes and others having patterns similar to the extinct southern population of Burchell's zebra, where the stripes covered most of the body except for the hind parts, legs and belly.[13] It also had a broad dark dorsal stripe on its back. It had a standing mane with brown and white stripes.[8]

The only quagga to have been photographed alive was a mare at the Zoological Society of London's Zoo. Five photographs of this specimen are known, taken between 1863 and 1870.[25] On the basis of photographs and written descriptions, many observers suggest that the stripes on the quagga were light on a dark background, unlike other zebras. The German naturalist Reinhold Rau, pioneer of the Quagga Project, claimed that this is an optical illusion: that the base colour is a creamy white and that the stripes are thick and dark.[13] Embryological evidence supports zebras being dark coloured with white as an addition.[26]

Living in the very southern end of the plains zebra's range, the quagga had a thick winter coat that moulted each year. Its skull was described as having a straight profile and a concave diastema, and as being relatively broad with a narrow occiput.[10][27] Like other plains zebras, the quagga did not have a dewlap on its neck as the mountain zebra does.[11] The 2004 morphological study found that the skeletal features of the southern Burchell's zebra population and the quagga overlapped, and that they were impossible to distinguish. Some specimens also appeared to be intermediate between the two in striping, and the extant Burchell's zebra population still exhibits limited striping. It can therefore be concluded that the two subspecies graded morphologically into each other. Today, some stuffed specimens of quaggas and southern Burchell's zebra are so similar that they are impossible to definitely identify as either, since no location data was recorded.[10]

Behaviour and ecology

The quagga was the southernmost distributed plains zebra, mainly living south of the Orange River. It was a grazer, and its habitat range was restricted to the grasslands and arid interior scrubland of the Karoo region of South Africa, today forming parts of the provinces of Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, Western Cape and the Free State.[13][28] These areas were known for distinctive flora and fauna and high amounts of endemism.[27][29] Quaggas have been reported gathering into herds of 30–50, and sometimes travelled in a linear fashion.[13] They may have been sympatric with Burchell's zebra between the Vaal and Orange rivers.[10][29] This is disputed,[10] and there is no evidence that they interbred.[29] It could also have shared a small portion of its range with Hartmann's mountain zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae).[20]

Little is known about the behaviour of quaggas in the wild, and it is sometimes unclear what exact species of zebra is referred to in old reports.[13] The only source that unequivocally describes the quagga in the Free State is that of the British military engineer and hunter Major Sir William Cornwallis Harris.[10] His 1840 account reads as follows:

The geographical range of the quagga does not appear to extend to the northward of the river Vaal. The animal was formerly extremely common within the colony; but, vanishing before the strides of civilisation, is now to be found in very limited numbers and on the borders only. Beyond, on those sultry plains which are completely taken possession of by wild beasts, and may with strict propriety be termed the domains of savage nature, it occurs in interminable herds; and, although never intermixing with its more elegant congeners, it is almost invariably to be found ranging with the white-tailed gnu and with the ostrich, for the society of which bird especially it evinces the most singular predilection. Moving slowly across the profile of the ocean-like horizon, uttering a shrill, barking neigh, of which its name forms a correct imitation, long files of quaggas continually remind the early traveller of a rival caravan on its march. Bands of many hundreds are thus frequently seen doing their migration from the dreary and desolate plains of some portion of the interior, which has formed their secluded abode, seeking for those more luxuriant pastures where, during the summer months, various herbs thrust forth their leaves and flowers to form a green carpet, spangled with hues the most brilliant and diversified.[30]

Since the practical function of striping has not been determined for zebras in general, it is unclear why the quagga lacked stripes on its hind parts. A cryptic function for protection from predators (stripes obscure the individual zebra in a herd) and biting flies (which are less attracted to striped objects), as well as various social functions, have been proposed for zebras in general. Differences in hind quarter stripes may have aided species recognition during stampedes of mixed herds, so that members of one subspecies or species would follow its own kind. It has also been evidence that the zebras developed striping patterns as thermoregulation to cool themselves down, and that the quagga lost them due to living in a cooler climate,[31][32] although one problem with this is that the mountain zebra lives in similar environments and has a bold striping pattern.[32] A 2014 study strongly supported the biting-fly hypothesis, and the quagga appears to have lived in areas with lesser amounts of fly activity than other zebras.[33]

A 2020 study suggested that the sexual dimorphism in size, with quagga mares being larger than stallions, could be due to the cold and droughts that affects the Karoo plateau, conditions that were even more severe in prehistoric times, such as during ice ages (other plains zebras live in warmer areas). Isolation, cold, and aridity could thereby have affected quagga evolution, including coat colour and size dimorphism. Sinze plains zebra mares are pregnant or lactate for much of their lives, larger size could have been a selective advantage for quagga mares, as they would therefore have more food reserves when food was scarce. Dimorphism and coat colour could also have evolved through genetic drift due to isolation, but these influences are not mutually exclusive, and could have worked together.[24]

Relationship with humans

Quaggas have been identified in cave art attributed to the indigenous San people of Southern Africa.[34] As it was easy to find and kill, the quagga was hunted by early Dutch settlers and later by Afrikaners to provide meat or for their skins. The skins were traded or used locally. The quagga was probably vulnerable to extinction due to its limited distribution, and it may have competed with domestic livestock for forage.[35] Local farmers used them as guards for their livestock, as they were likely to attack intruders.[35] Quaggas were said to be lively and highly strung, especially the stallions. Quaggas were brought to European zoos, and an attempt at captive breeding at London Zoo, but was halted when a lone stallion killed itself by bashing itself against a wall after losing its temper.[36] On the other hand, captive quaggas in European zoos were said to be tamer and more docile than Burchell's zebra.[13] One specimen was reported to have lived in captivity for 21 years and 4 months, dying in 1872.[13]

The quagga was long regarded a suitable candidate for domestication, as it counted as the most docile of the zebras. The Dutch colonists in South Africa had considered this possibility, because their imported work horses did not perform very well in the extreme climate and regularly fell prey to the feared African horse sickness.[37][38] In 1843, the English naturalist Charles Hamilton Smith wrote that the quagga was 'unquestionably best calculated for domestication, both as regards strength and docility'. Some mentions have been given of tame or domesticated quaggas in South Africa. In Europe, two stallions were used to drive a phaeton by the sheriff of London in the early 19th century.[39][40]

In an attempt at domesticating the quagga, the British lord George Douglas, 16th Earl of Morton obtained a single male which he bred with a female horse of partial Arabian ancestry. This produced a female hybrid with stripes on its back and legs. Lord Morton's mare was sold and was subsequently bred with a black stallion, resulting in offspring that again had zebra stripes. An account of this was published in 1820 by the Royal Society.[41][42] It is unknown what happened to the hybrid mare itself. This led to new ideas on telegony, referred to as pangenesis by the British naturalist Charles Darwin.[28] At the close of the 19th century, the Scottish zoologist James Cossar Ewart argued against these ideas and proved, with several cross-breeding experiments, that zebra stripes could appear as an atavistic trait at any time.[43][44]

There are 23 known stuffed and mounted quagga specimens throughout the world, including a juvenile, two foals, and a foetus. In addition, a mounted head and neck, a foot, seven complete skeletons, and samples of various tissues remain. A 24th mounted specimen was destroyed in Königsberg, Germany, during World War II, and various skeletons and bones have also been lost.[45][46]

Extinction

The quagga had disappeared from much of its range by the 1850s. The last population in the wild, in the Orange Free State, was extirpated in the late 1870s.[13] The last known wild quagga died in 1878.[35] The specimen in London died in 1872 and the one in Berlin in 1875. The last captive quagga, a female in Amsterdam's Natura Artis Magistra zoo, lived there from 9 May 1867 until it died on 12 August 1883, but its origin and cause of death are unclear.[15] Its death was not recognised as signifying the extinction of its kind at the time, and the zoo requested another specimen; hunters believed it could still be found "closer to the interior" in the Cape Colony. Since locals used the term quagga to refer to all zebras, this may have led to the confusion. The extinction of the quagga was internationally accepted by the 1900 Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa. The last specimen was featured on a Dutch stamp in 1988.[47]

In 1889, the naturalist Henry Bryden wrote: "That an animal so beautiful, so capable of domestication and use, and to be found not long since in so great abundance, should have been allowed to be swept from the face of the earth, is surely a disgrace to our latter-day civilization."[48]

Breeding back project

After the very close relationship between the quagga and extant plains zebras was discovered, Rau started the Quagga Project in 1987 in South Africa to create a quagga-like zebra population by selectively breeding for a reduced stripe pattern from plains zebra stock, with the eventual aim of introducing them to the quagga's former range. To differentiate between the quagga and the zebras of the project, they refer to it as "Rau quaggas".[28] The founding population consisted of 19 individuals from Namibia and South Africa, chosen because they had reduced striping on the rear body and legs. The first foal of the project was born in 1988. Once a sufficiently quagga-like population has been created, participants in the project plan to release them in the Western Cape.[18][49]

Introduction of these quagga-like zebras could be part of a comprehensive restoration programme, including such ongoing efforts as eradication of non-native trees. Quaggas, wildebeest, and ostriches, which occurred together during historical times in a mutually beneficial association, could be kept together in areas where the indigenous vegetation has to be maintained by grazing. In early 2006, the third- and fourth-generation animals produced by the project were considered looking much like the depictions and preserved specimens of the quagga. This type of selective breeding is called breeding back. The practice is controversial, since the resulting zebras will resemble the quaggas only in external appearance, but will be genetically different. The technology to use recovered DNA for cloning has not yet been developed.[2][50]

See also

References

- Hack, M. A.; East, R.; Rubenstein, D. I. (2008). "Equus quagga quagga". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- Max, D. T. (1 January 2006). "Can You Revive an Extinct Animal?". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Rebuilding a Species". VOA. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- "Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- Quagga at yourdictionary.com

- Möller, Lucie. Of the same breath: indigenous animal and place names. Bloemfontein: Sun Press. ISBN 978-1-928424-02-4.

- Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T (2005). "Equidae". The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 537–546. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Quagga". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Quagga". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Groves, C.; Grubb, P. (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4214-0093-8.

- Groves, C. P.; Bell, C. H. (2004). "New investigations on the taxonomy of the zebras genus Equus, subgenus Hippotigris". Mammalian Biology - Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 69 (3): 182. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00133.

- Azzaroli, A.; Stanyon, R. (1991). "Specific identity and taxonomic position of the extinct Quagga". Rendiconti Lincei. 2 (4): 425. doi:10.1007/BF03001000. S2CID 87344101.

- Groves, C. P.; Willoughby, D. P. (1981). "Studies on the taxonomy and phylogeny of the genus Equus. 1. Subgeneric classification of the recent species". Mammalia. 45 (3). doi:10.1515/mamm.1981.45.3.321. S2CID 83546368.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. 1. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1024–1025. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- St. Leger, J. (1932). "LXVII.—On Equus quagga of South-western and Eastern Africa". Journal of Natural History. Series 10. 10 (60): 587–593. doi:10.1080/00222933208673614.

- Van Bruggen, A.C. (1959). "Illustrated notes on some extinct South African ungulates". South African Journal of Science. 55: 197–200.

- Schlawe, L.; Wozniak, W. (2010). "Über die ausgerotteten Steppenzebras von Südafrika QUAGGA und DAUW, Equus quagga quagga". Zeitschrift des Kölner Zoos (in German). 2: 97–128.

- Smith, C. H. (1841). The Natural History of Horses: The Equidae or Genus Equus of Authors (PDF). Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars. p. 388. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.21334.

- Harley, E.H.; Knight, M.H.; Lardner, C.; Wooding, B.; Gregor, M. (2009). "The Quagga Project: Progress over 20 years of selective breeding" (PDF). South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 39 (2): 155. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.653.4113. doi:10.3957/056.039.0206. S2CID 31506168.

- Higuchi, R.; Bowman, B.; Freiberger, M.; Ryder, O. A.; Wilson, A. C. (1984). "DNA sequences from the quagga, an extinct member of the horse family". Nature. 312 (5991): 282–284. Bibcode:1984Natur.312..282H. doi:10.1038/312282a0. PMID 6504142. S2CID 4313241.

- Hofreiter, M.; Caccone, A.; Fleischer, R. C.; Glaberman, S.; Rohland, N.; Leonard, J. A. (2005). "A rapid loss of stripes: The evolutionary history of the extinct quagga". Biology Letters. 1 (3): 291–295. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0323. PMC 1617154. PMID 17148190.

- Lowenstein, J. M.; Ryder, O. A. (1985). "Immunological systematics of the extinct quagga (Equidae)". Experientia. 41 (9): 1192–1193. doi:10.1007/BF01951724. PMID 4043335. S2CID 27281662.

- Higuchi, R. G.; Wrischnik, L. A.; Oakes, E.; George, M.; Tong, B.; Wilson, A. C. (1987). "Mitochondrial DNA of the extinct quagga: Relatedness and extent of postmortem change". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 25 (4): 283–287. Bibcode:1987JMolE..25..283H. doi:10.1007/BF02603111. PMID 2822938. S2CID 28973189.

- Pedersen, Casper-Emil T.; Albrechtsen, Anders; Etter, Paul D.; Johnson, Eric A.; Orlando, Ludovic; Chikhi, Lounes; Siegismund, Hans R.; Heller, Rasmus (22 January 2018). "A southern African origin and cryptic structure in the highly mobile plains zebra". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (3): 491–498. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0453-7. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 29358610. S2CID 3333849.

- Heywood, P. (2019). "Sexual dimorphism of body size in taxidermy specimens of Equus quagga quagga Boddaert (Equidae)". Journal of Natural History. 53 (45–46): 2757–2761. doi:10.1080/00222933.2020.1736678.

- Huber, W. (1994). "Dokumentation der fünf bekannten Lebendaufnahmen vom Quagga, Equus quagga quagga Gmelin, 1788 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae)". Spixiana (in German). 17: 193–199.

- Prothero, D. R.; Schoch, R. M. (2003). Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8018-7135-1.

- Kingdon, J. (1988). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part B: Large Mammals. University of Chicago Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-226-43722-4.

- Heywood, P. (2013). "The quagga and science: What does the future hold for this extinct zebra?". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 56 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1353/pbm.2013.0008. PMID 23748526. S2CID 7991775.

- Hack, M. A.; East, R.; Rubenstein, D. I. (2002). "Status and Action Plan for the Plains Zebra (Equus burchelli)". In Moehlman, P. D. R. (ed.). Equids: Zebras, Asses, and Horses: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. p. 44. ISBN 978-2-8317-0647-4.

- Sir Cornwallis Harris, quoted in Duncan, F. M. (1913). Cassell's natural history. London: Cassell. pp. 350–351. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Larison, B.; Harrigan, R. J.; Thomassen, H. A.; Rubenstein, D. I.; Chan-Golston, A. C.; Li, E.; Smith, T. B. (2015). "How the zebra got its stripes: a problem with too many solutions". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (1): 140452. Bibcode:2015RSOS....240452L. doi:10.1098/rsos.140452. PMC 4448797. PMID 26064590.

- Ruxton, G. D. (2002). "The possible fitness benefits of striped coat coloration for zebra". Mammal Review. 32 (4): 237–244. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.2002.00108.x.

- Caro, T.; Izzo, A.; Reiner, R. C.; Walker, H.; Stankowich, T. (2014). "The function of zebra stripes". Nature Communications. 5: 3535. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3535C. doi:10.1038/ncomms4535. PMID 24691390.

- Ouzman, S.; Taçon, P. S. C.; Mulvaney, K.; Fullager, R. (2002). "Extraordinary Engraved Bird Track from North Australia: Extinct Fauna, Dreaming Being and/or Aesthetic Masterpiece?". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 12: 103–112. doi:10.1017/S0959774302000057.

- Weddell, B. J. (2002). Conserving Living Natural Resources: In the Context of a Changing World. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-78812-0.

- Piper, R. (20 March 2009). Extinct animals: an encyclopedia of species that have disappeared during human history. Greenwood Press. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-0-313-34987-4. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- van Grouw, K. (2018). Unnatural Selection. Princeton University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9780691157061.

- Ridgeway, W. (1905). "The Origin and Influence of the Thoroughbred Horse". Cambridge Biological Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 76–78. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.24156.

- Smith, C. H. (1841). The Natural History of Horses. Edinburgh: W. H. Lizar. p. 331. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.21334.

- L., R. (1901). "Some Animals Exterminated During the Nineteenth Century". Nature. 63 (1628): 252–254. doi:10.1038/063252e0.

- Morton, Earl of (1821). "A Communication of a Singular Fact in Natural History". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 111: 20–22. ISSN 0261-0523. JSTOR 107600.

- Birkhead, T. R. (2003). A Brand New Bird: How Two Amateur Scientists Created the First Genetically Engineered Animal. Basic Books. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-465-00665-6.

- Ewart, J. C. (1899). The Penycuik Experiments. London: A. and C. Black. pp. 55–161. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.25674.

- Weeks, D. E. (2001). "Newton Morton's influence on genetics: The Morton number". Advances in Genetics. 42: 7–10. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(01)42011-6. ISBN 9780120176427. PMID 11037310.

- Rau, R. E. (1974). "Revised list of the preserved material of the extinct Cape colony quagga, Equus quagga quagga (Gmelin)". Annals of the South African Museum. Annale van die Suid-Afrikaanse Museum. 65: 41–87.

- Rau, R. E. (1978). "Additions to the revised list of preserved material of the extinct Cape Colony quagga and notes on the relationship and distribution of southern plains zebras". Annals of the South African Museum. 77: 27–45. ISSN 0303-2515.

- De Vos, R. (2014). "Stripes faded, barking silenced: remembering quagga". Animal Studies Journal. 3 (1). ISSN 2201-3008.

- Bryden, H. (1889). Kloof and Karoo. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 393–403. ASIN B00CNE0EZC.

- "Zebra cousin became extinct 100 years ago. Now, it's back". CNN.

- Freeman, C. (2009). "Ending Extinction: The Quagga, the Thylacine, and the 'Smart Human'". Leonardo's Choice. pp. 235–256. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2479-4_13. ISBN 978-90-481-2478-7.

_mare%252C_showing_the_disappearance_of_stripes_characteristic_of_the_%22Quagga%22_proper_(now_extinct)_..._(50220991353).jpg.webp)

_one_of_them_presenting_an_extreme_reduction_of_the_%22zebra%22_pattern_......_(32309547213).jpg.webp)