Kastrati (tribe)

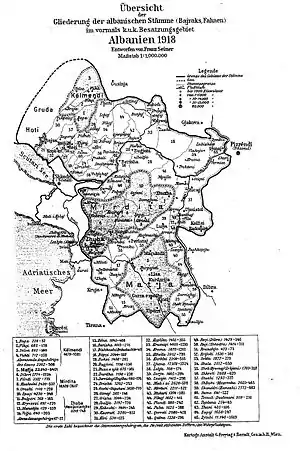

The Kastrati is a historical Albanian tribe (fis) and region in northwestern Albania.[1] It is part of the Malësia region. Administratively, the region is located in the Malësi e Madhe District, part of the Kastrati municipal unit.[1] The centre of Kastrati is the village of Bajzë. As an area and kin group it is mentioned in 1403 and then in 1416 in Venetian archives. Kastrati is a community based on kinship and territorial ties that are traced back to the common ancestor of most of its brotherhoods (vllazni), Detal Bratoshi.

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

Geography

Kastrati is located in northwestern Albania, Shkodër County near the Albania-Montenegro border. The region is wholly included in the Kastrat municipal unit about 26km to the east. In terms of historical divisions, it borders Hoti to the north, the town of Koplik to the south, Kelmendi and Boga to the northeast and Shkreli to the east. Kastrati borders the Shkodra Lake to the west. This part of the lake that is traditionally used by Kastrati is called Viri.

Kastrati is divided into two sub-regions: the mountainous Katund i Kastratit and the lowland Bajzë area. The settlement of Bajzë itself is the center of Kastrati. This division reflects the organization of Kastrati's economy, which is a combination of agricultural and livestock activities. All families of Kastrati have property in both areas. Bajzë includes: Aliaj, Jeran, Gradec, Vukpalaj, Ivanaj, Pjetroshan and Katund i Kastratit includes: Goraj, Budishë and Bratosh.[2]

In the Ottoman period, some villages like Kamicë-Flakë were put under the bajrak (military administrative unit) of Kastrati, but are not part of this region. They are related to the wider Vraka area in terms of cultural ties. [3] Thus, today Kamica is not placed in the Kastrati municipal unit, but in Qendër.

Origins

Oral traditions are the first accounts about Kastrati's origins. In the beginning of the 20th century, archival records yielded more historically grounded observations. Almost all of Kastrati's brotherhoods descend from the figure of Detal Bratoshi, thus have no endogamous relations within Kastrati. The name Kastrati itself is the name of a settlement and small tribe that lived in that exact area before the Ottoman conquest of Albania in the 15th century.

Kastrati is first mentioned in 1403 when its leader Alexius, head of three villages appears to be awarded gifts by the Venetian governor of Scutari.[4][5] Alexius Kastrati reappears as head of Kastrati in the Venetian cadastre of Scutari in 1416-7. His immediate kin included Alexius Kastrati the Younger, Pal, Markjen and Lazër Kastrati.[6] A Jon Stronga also appears in their main settlement.

Konstantin Jireček recorded a story that linked them to Kuči through a supposed great-grandson of Kastrati named Krsto, who was allegedly the brother of Grča, son of Nenad, ancestor of Old Kuči.[7] In historical record, Kastrati and the Old Kuči appear in different areas and timelines as Old Kuči formed part of the tribe of current Kuči, which was based on different ancestral groups in the late 15th century .[8] Nevertheless, if not kin by blood, Montenegrin and Albanian tribes regarded closeness in original or home territory from where someone "came". Therefore, Serbian geographer Andrija Jovićević put forward the narrative that the Kuči were "kin" to Kastrati, Berisha and Kelmendi because their distant ancestor once, ostensibly, settled in the same general area as Kuči.[9]

In later times, one brotherhood of Kuči, the Drekaloviči traced their descent to Berisha. In turn, from them a part of the Kastrati trace their origin in the 16th century. Thus, these groups have the custom of avoiding intermarriage with each other.[10] From this brotherhood descended the semi-legendary figure of Detal Bratoshi (alternatively recorded as Dedli or Del), who is the ancestor of the majority of brotherhoods of Kastrati.[11]

Families

Johann Georg von Hahn registered 408 families with 3,157 people living in two groups of families: highland and lowland. Highland families were Martinaj, Gjokaj, Theresi, Bradosoi, Budischia, Kurtaj, Goraj and Pjetroviç while lowland families were Puta, Copani, Hikuzzaj, Skandsehi, Pjetrosçinaj, Moxetti, Dobrovoda and Aliaj. All of them were Catholics except the Aliaj, who were Muslims.[12] In the late Ottoman period, the tribe of Kastrati consisted of 300 Catholic and 200 Muslim households.[13]

Religion and economy

The predominant religion in Kastrati is Roman Catholicism.[14][15] The Kastrati celebrate the feast of St. Mark.[16] They have traditionally supported themselves with livestock and agriculture.[17]

History

The Kastrati clan was recorded for the first time in 1416.[18] The clan's centre was once at the ruins of a Roman castra on the Scutari-Orosh road.[19]

In Mariano Bolizza's 1614 report, Kastrati had 50 households and 130 men-in-arms led by Prenk Bitti.[20]

In 1831, during the Ottoman attack against Montenegro, the Kastrati and other clans of Northern Albania expressed their support of Montenegro and refused to participate on the Ottoman side.[21] In 1832 they joined Montenegrin forces and defeated Ottoman forces on Hoti mountain.[22] According to the Treaty of San Stefano the region of Kastrati (together with Hoti, Kelmendi and Grudë) was to be annexed to Montenegro, but after the Treaty of Berlin was signed in 1878 this decision was changed and Kastrati remained in the Ottoman Empire.[23] However, as other Albanian-inhabited areas were formally annexed to Montenegro the delimitation process was not concluded. In 1883 Kastrati, Hoti, Gruda and Shkreli formed another pact to prevent the delimitation of the expanded Montenegrin borders.[24]

After the Young Turk Revolution (1908) and subsequent restoration of the Ottoman constitution, the Kastrati tribe made a besa (pledge) to support the document and to stop blood feuding with other tribes until November 6.[25] During the Albanian revolt of 1911 on 23 June Albanian tribesmen and other revolutionaries gathered in Montenegro and drafted the Greçë Memorandum demanding Albanian sociopolitical and linguistic rights with five of the signatories being from Kastrati.[26] In later negotiations with the Ottomans, an amnesty was granted to the tribesmen with promises by the government to build one to two primary schools in the nahiye of Kastrati and pay the wages of teachers allocated to them.[26]

Kastrati was a battleground area during the Balkan Wars. During the Siege of Scutari in 1912/1913 Catholics from Kastrati, Hoti and Grude, joined the forces of Kingdom of Montenegro and robbed and burned houses of Muslim members of their clans who retreated to the Ottoman-controlled fortress of Scutari.[27][28]

On May 26, 1913, a delegation from the chief families of Hoti, Gruda, Kelmendi, Shkreli and Kastrati met Admiral Cecil Burney of the international fleet and petitioned against the annexation of Hoti and Gruda by Montenegro. The delegation warned that hostilities would resume if those areas didn't remain "entirely Albanian".[29] Eventually, due to the influence of Austria, the region of Kastrati was incorporated into the newly formed Kingdom of Albania, although it was agreed with some of the Great Powers that it should be annexed to Montenegro.[30]

See also

- List of clans of Albania

References

- Elsie, Robert (2010) [2004], Historical Dictionary Of Albania (PDF) (2 ed.), Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, p. 226, ISBN 9781282521926, OCLC 816372706, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06,

The Kastrati region is situated in the District of Malësia e Madhe east and northeast of Bajza.

- Shkurtaj, Gjovalin (2013). E folmja e Kastratit. pp. 3–5. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Steinke, Klaus; Ylli, Xhelal (2013). Die slavischen Minderheiten in Albanien (SMA). 4. Teil: Vraka - Borakaj. Munich: Verlag Otto Sagner. ISBN 9783866883635. p. 9. "Am östlichen Ufer des Shkodrasees gibt es heute auf dem Gebiet von Vraka vier Dörfer, in denen ein Teil der Bewohner eine montenegrinische Mundart spricht. Ferner zählen zu dieser Gruppe noch die Dörfer Shtoji i Ri und Shtoji i Vjetër in der Gemeinde Rrethinat und weiter nordwestlich von Koplik das Dorf Kamica (Kamenica), das zur Gemeinde Qendër in der Region Malësia e Madhe gehört. Desgleichen wohnen vereinzelt in der Stadt sowie im Kreis Shkodra weitere Sprecher der montenegrinischen Mundart. Nach ihrer Konfession unterscheidet man zwei Gruppen, d.h. orthodoxe mid muslimische Slavophone. Die erste, kleinere Gruppe wohnt in Boriçi i Vogël, Gril, Omaraj und Kamica, die zweite, größere Gruppe in Boriçi i Madh und in Shtoj."

- Mary Edith Durham (1928). Some clannish origins, laws and customs of the Balkans. George Allen & Unwin. p. 22. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

The Kastrati were evidently a powerful clan, for in 1403 we find Alexius Kastrati headman in a list of Albanian chiefs who are rewarded by the Venetians with gifts of cloth.

- Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti (1983). Glas. p. 109. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Почетком XV века сусрећу се и клице данашњег племена Кастрати, чији је праотац био неки Крсто. Алекса Кастрати добио је 1403...

- Zamputi, Injac (1977). Regjistri i kadastrēs dhe i koncesioneve pēr rrethin e Shkodrës 1416-1417. Academy of Sciences of Albania. p. 65. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Konstantin Jireček (1923). Istorija Srba. Izdavačka knjižarnica G. Kona. p. 58. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

По предању, родоначелник Куча био је Грча Ненадин, од чијих пет синова, Петра, Ђурђа, Тиха, Леша и Мара потичу њихова братства. Праотац Кастрата је Крсто, а Шаљана Шако; обојица су тобоже били браћа нареченог Грчина, док би Берише били потомци баш самога Грче.

- Kaser, Karl (1992). Hirten, Kämpfer, Stammeshelden: Ursprünge und Gegenwart des balkanischen Patriarchats. Böhlau Verlag Wien. p. 150. ISBN 3205055454. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Jovićević, Andrija (1923). Малесија. Срп. етн. зборник XXVII. SANU. pp. 60–61. OCLC 635033682.

- Durham, Edith (1928). Some tribal origins, laws and customs of the Balkans. pp. 30, 52. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Elsie, Robert (30 May 2015). Robert Elsie. p. 70. ISBN 9781784534011.

- Johann Georg Hahn (1854). Heft. Geographisch-ethnographische Uebersicht. Reiseskizzen. Sittenschilderungen. Sind die Albanesen Autochthonen? Das albanische Alphabet. Historisches. Verlag von Friedrich Mauke. p. 192. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 31.

- Milorad Ekmečić (1989). Stvaranje Jugoslavije 1790-1918. Prosveta. p. 121. ISBN 9788607004324. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

...кастрати били су католици..

- Istorijski glasnik. Naučna knjiga. 1960. p. 189. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Кастрати су одреда католичке вере

- Modern Greek Studies Yearbook. University of Minnesota. 1992. p. 26. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Glasnik Jugoslovenskog Profesorskog Drustva. 1924. p. 37. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Кастрати су земљорадници и сточари

- Elsie, Robert (2010) [2004], Historical Dictionary Of Albania (PDF) (2 ed.), Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, p. 226, ISBN 9781282521926, OCLC 816372706, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06

- Milan Šufflay (2000). Izabrani politički spisi. Matica hrvatska. p. 136. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Kastrati, kojima je embrio sjedio kod ruševina rimskog "Kastra" (tabora, Iminacium?) viđenih još g. 1559. na cesti Skadar - Oroši

- The Tribes of Albania; History, Society and Culture. Robert Elsie. 30 May 2015. p. 69. ISBN 9781784534011.

- Vladimir Stojančević (1990). Srbija i oslobodilački pokret na Balkanskom poluostrvu u XIX veku. Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva. p. 103. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Овога пута, северноалбанска племена Клементи, Хоти, Груди и Кастрати солидарисали су

- Sadulla Brestovci (1983). Marrëdhëniet shqiptare--serbo-malazeze (1830-1878). Instituti Albanologjik i Prishtinës. p. 260. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

A sledece godine albanska plemena (Hoti, Kastrati, Grude, Kelmendi) pomogle su crnogorskim plemenima da poraze turksu vojsku na Hotskoj Gori.

- Љубодраг Димић; Đorđe Borozan (1999). Југословенска држава и Албанци. Службени лист СРЈ. p. 123. ISBN 978-86-355-0440-7. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

...тако да су племена Кастрати, Климеити, Хоти, Груде била припо]ена Црно] Гори. Али, на Берлинском конгресу

- Miller, William (2012-10-12). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors 1801-1927. Routledge. p. 356. ISBN 9781136260469. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 159.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 186–187. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Dragoslav Srejović; Slavko Gavrilović; Sima M. Ćirković (1983). Istorija srpskog naroda: knj. Od Berlinskog kongresa do Ujedinjenja 1878-1918 (2 v.). Srpska književna zadruga. p. 248. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Пут до пред сам Скадар био је слободан. Црногорској војсци придружила су се албанска католичка племена Груди, Хоти и Кастрати, преко чијег је земљишта пролазила војска, и тако је њена позадина Оила обезбеђена.

- Nikola P. Škerović (1964). Crna Gora na osvitku xx [i.e. dvadesetog] vijeka. Naučno delo. p. 581. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

Албанска католичка племена Груди, Хоти, Кастрати, преко чијег земљишта су прелазиле црногорске трупе у правцу Скадра, пристала су уз црногорске трупе и испред њих, све до српског насеља Враке, испред самог Скадра, попалила и опљачкала куће оних својих муслиманских саплеменика који су напустили своје домове и одлучили да се ставе под заштиту турских трупа у Скадру.

- Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: A Modern History. I.B.Tauris. p. 73. ISBN 9781860645419. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Lambert Ehrlich; Marija Vrečar (2002). Pariška mirovna konferencia in Slovenci 1919/20. Inštitut za zgodovino Cerkve pri Teološki fakulteti Univerze v Ljubljani. p. 201. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

Vsled vpliva Avstrije se albanski plemeni Klementi in Kastrati nista priključili Črni gori, in tudi ob Bojani seji je odreklo na...