Knight of the Swan

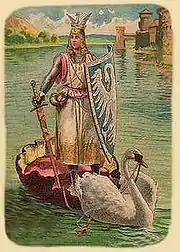

The story of the Knight of the Swan, or Swan Knight, is a medieval tale about a mysterious rescuer who comes in a swan-drawn boat to defend a damsel, his only condition being that he must never be asked his name.

The earliest versions (preserved in Dolopathos) do not provide specific identity to this knight, but the Old French Crusade cycle of chansons de geste adopted it to make the Swan Knight (Le Chevalier au Cigne, first version around 1192) the legendary ancestor of Godfrey of Bouillon. The Chevalier au Cigne, also known as Helias, figures as the son of Orient of L'Islefort (or Illefort) and his wife Beatrix in perhaps the most familiar version, which is the one adopted for the late fourteenth century Middle English Cheuelere Assigne.[1] The hero's mother's name may vary from Elioxe (probably a mere echo of Helias) to Beatrix depending on the text, and in a Spanish version, she is called Isomberte.

At a later time, the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach incorporated the swan knight Loherangrin into his Arthurian epic Parzival (first quarter of the 13th century). A German text, written by Konrad von Würzburg in 1257, also featured a Swan Knight without a name. Wolfram's and Konrad's were used to construct the libretto for Richard Wagner's opera Lohengrin (Weimar 1850).[2]

Another example of the motif is Brangemuer, the knight that lay dead in a boat tugged by a swan, and whose adventure was taken up by Gawain's brother Guerrehet (Gareth or Gaheris) in the first Continuation to Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval.

Swan Children

On his notes on The Children of Lir tale, in his book More Celtic Fairy Tales, folklorist Joseph Jacobs wrote that the "well-known Continental folk-tale" of The Seven Swans (or Ravens) became connected to the medieval cycle of the Knight of the Swan.[3]

The "Swan-Children" appears to have been originally separate from the Godfrey cycle and the Swan Knight story generally.[4] Paris identifies four groups of variants, which he classifies usually by the name of the mother of the swan children.[5]

The tale in all variants resemble not only such chivalric romances as The Man of Law's Tale and Emaré, but such fairy tales as The Girl Without Hands.[6] It also bears resemblance to the fairy tale The Six Swans, where brothers transformed into birds are rescued by the efforts of their sister.[7]

Dolopathos

Included in Johannes de Alta Silva's Dolopathos sive de Rege et Septem Sapientibus (ca. 1190), a Latin version of the Seven Sages of Rome is a story of the swan children which has served as a precursor to the poems of the Crusade cycle.[8] The tale was adapted into the French Li romans de Dolopathos by the poet Herbert.[9] The story is as follows:[8][10]

A nameless young lord becomes lost in the hunt for a white stag and wanders into an enchanted forest where he encounters a mysterious woman (clearly a swan maiden or fairy) in the act of bathing, while clutching a gold necklace. They fall instantly for each other and consummate their love. The young lord brings her to his castle, and the maiden (just as she has foretold) gives birth to a septuplet, six boys and a girl, with golden chains about their necks. But her evil mother-in-law swaps the newborn with seven puppies. The servant with orders to kill the children in the forest just abandons them under a tree. The young lord is told by his wicked mother that his bride gave birth to a litter of pups, and he punishes her by burying her up to the neck for seven years. Some time later, the young lord while hunting encounters the children in the forest, and the wicked mother's lie starts to unravel. The servant is sent out to search them, and find the boys bathing in the form of swans, with their sister guarding their gold chains. The servant steals the boys' chains, preventing them from changing back to human form, and the chains are taken to a goldsmith to be melted down to make a goblet. The swan-boys land in the young lord's pond, and their sister, who can still transform back and forth into human shape by the magic of her chain, goes to the castle to obtain bread to her brothers. Eventually the young lord asks her story so the truth comes out. The goldsmith was actually unable to melt down the chains, and had kept them for himself. These are now restored back to the six boys, and they regain their powers, except one, whose chain the smith had damaged in the attempt. So he alone is stuck in swan form. The work goes on to say obliquely hints that this is the swan in the Swan Knight tale, more precisely, that this was the swan “quod cathena aurea militem in navicula trahat armatum (that tugged by a gold chain an armed knight in a boat).”[8]

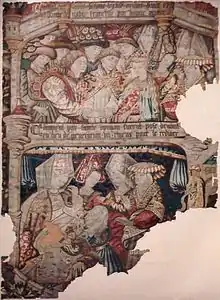

Crusade cycle: La Naissance du Chevalier au Cygne

The Knight of the Swan story appears in the Old French chansons de geste of the first Crusade cycle, establishing a legendary ancestry of Godfrey of Bouillon, who in 1099 became ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Godfrey loomed large in the medieval Christian imagination, and his shadowy genealogy became a popular subject for writers of the period.

The swan-children tale occurs in the first or La Naissance du Chevalier au Cygne branch of the cycle. The texts can be classed into four versions, 1) Elioxe, 2) Beatrix, 3) an Elioxe-Beatrix composite, and 4) Isomberte. Of Isomberte no French copy survives, and it's known only from the Spanish Gran conquista de Ultramar.[11] (Gaston Paris also used a somewhat similar classification scheme for swan-children cognate tales which he refers to as Version I.[4])

Elioxe follows the Dolopathos tale closest, but tells a courtlier version of the story,[11] replacing the young lord who becomes lost with King Lothair, a ruler from beyond Hungary and the maiden with Elioxe. Lothair loses his way and stops by a fountain, and while asleep, is tended by Elioxe who comes out of the woodworks of the mountains. King Lothair decides to wed her, despite his mother's protest. However Elioxe foretells her own death giving birth to seven children, and that one of the offspring shall be king of the Orient.

While Lothair is absent warring, the queen mother Matrosilie orders a servant to carry the children in two baskets and expose them in the forest, and prepares the lie that their mother gave birth to serpents and died from their bites. The servant however had left the children by the hermit's hut, so they survive, and seven years later are discovered by a greedy courtier named Rudemart. Allured by the gold chains the children are wearing, he obtains instruction from the queen mother to steal them, but failing to take account of their numbers, misses the chain belonging to the girl. The six boys bereft of the chains fly out in swan form, and their father Lothair issues an order of protection. The king's nephew tries to hunt one of the birds to please him, but the king in a fit hurls a gold basin which breaks. Matrosilie then provides one of the necklaces to make the repair. Eventually the truth is untangled through the sister of the swan siblings. All the boys regain human form but one. While other seek their own fortunes, one boy cannot part with his brother turned permanently into a swan, and becomes Swan Knight.[11]

In the Beatrix variants, the woman had taunted another woman over her alleged adultery, citing a multiple birth as proof of it, and was then punished with a multiple birth of her own.[12] In the Beatrix versions, the mother is also an avenging justice.[13] In the Isomberte variants, the woman is a princess fleeing a hated marriage.[12]

Swan Knight

Version II involves the Swan Knight himself. These stories are sometimes attached to the story of the Swan Children, but sometimes appear independently, in which case no explanation of the swan is given. All of these describe a knight who appears with a swan and rescues a lady; he then disappears after a taboo is broken, but not before becoming the ancestor of an illustrious family.[14] Sometimes this is merely a brief account to introduce a descendant.[15] The second version of this tale is thought to have been written by the Norman trouvère Jean Renart.

In Brabant the name of the Knight of the Swan is Helias. It has been suggested that this connects him to the Greek solar god, Helios,[16] but the name is in fact a common variant of the name of the prophet Elijah, who nevertheless was connected to the Greek solar god by orthodox worship because of his association to Mount Horeb and a fire chariot.

Lohengrin

In the early 13th century, the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach adapted the Swan Knight motif for his epic Parzival. Here the story is attached to Loherangrin, the son of the protagonist Parzival and the queen of Pelapeire Condwiramurs. As in other versions Loherangrin is a knight who arrives in a swan-pulled boat to defend a lady, in this case Elsa of Brabant. They marry, but he must leave when she breaks the taboo of asking his name.

In the late 13th century, the poet Nouhusius (Nouhuwius) adapted and expanded Wolfram's brief story into the romance Lohengrin. The poet changed the title character's name slightly and added various new elements to the story, tying the Grail and Swan Knight themes into the history of the Holy Roman Empire.[17] In the 15th century an anonymous poet again took up the story for the romance Lorengel.[18] This version omits the taboo against asking about the hero's name and origins, allowing the knight and princess a happy ending.

In 1848, Richard Wagner adapted the tale into his popular opera Lohengrin, probably the work through which the Swan Knight story is best known today.[19]

Legacy

A Hungarian version of the story was collected by Hungarian journalist Elek Benedek, with the title Hattyú vitéz, and published in a collection of Hungarian folktales (Magyar mese- és mondavilág).[20]

Notes

- Gibbs 1868, pp. i-ii

- Jaffray 1910, p. 11

- Jacobs, Joseph. More Celtic fairy tales. New York: Putnam. 1895. pp. 221-222.

- Hibbard, Laura A. (1963). Medieval Romance in England. New York: Burt Franklin. p. 239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hibbard 1963, p. 240

- Schlauch, Margaret (1969). Chaucer's Constance and Accused Queens. New York: Gordian Press. p. 62.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schlauch (1969), p. 80.

- Mickel & Nelson 1977, Myer's essay, p.lxxxxi-

- Gerritsen & Van Melle 1998, Dictionary of Medieval Heroes, reprinted 2000, pp.247 "Seven Sages of Rome"

- Hibbard 1963, pp. 240-1

- Mickel & Nelson 1977, Myer's essay, p.xciii-

- Hibbard 1963, p. 242

- Schlauch (1969), p. 80–1.

- Hibbard 1963, p. 244

- Hibbard 1963, p. 245

- Hibbard 1963, p. 248

- Kalinke, Marianne E. (1991). "Lohengrin". In Lacy, Norris J. (ed.). The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. p. 239. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kalinke 1991, pp. 282–283

- Toner, Frederick L. (1991). "Richard Wagner". In Norris J. Lacy, The New Arthurian Encyclopedia, pp. 502–505. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4

- Benedek Elek. Magyar mese- és mondavilág. 2. kötet. Budapest: Athenaeum. [ca. 1894-1896] Tale nr. 75.

Bibliography

- Gerritsen, Willem Pieter; Van Melle, Anthony G. (1998). Dictionary of Medieval Heroes: Characters in Medieval Narrative Traditions and Their Afterlife in Literature, Theatre and the Visual Arts. Boydell Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Reprint: Boydell & Brewer 2000. ISBN 0851157807, 9780851157801 (preview)

- Gibbs, Henry H., ed. (1868). The Romance of the Cheuelere Assigne (Knight of the Swan). EETS Extra series. 6. London: N. Trübner.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (from the Medieval manuscript, British Library, MS Cotton Caligula A.ii.)

- Baring-Gould, S. Curious Myths Of The Middle Ages. Boston: Roberts Brothers. 1880. pp. 430-453.

- Jaffray, Robert (1910). The two knights of the swan, Lohengrin and Helyas: a study of the legend of the swan-knight, with special reference to its most important developments. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mickel, Emanuel J.; Nelson, Jan A., eds. (1977). La Naissance du Chevalier au Cygne (preview). The Old French Crusade Cycle. 1. Geoffrey M. Myers (essay). University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817385019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Elioxe ed. Mickel Jr., Béatrix ed. Nelson)

Further reading

- Alastair, Matthews. “When Is the Swan Knight Not the Swan Knight? Berthold Von Holle's Demantin and Literary Space in Medieval Europe.” The Modern Language Review, vol. 112, no. 3, 2017, pp. 666–685. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5699/modelangrevi.112.3.0666. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

- Barron, W. R. J. “‘CHEVALERE ASSIGNE’ AND THE ‘NAISSANCE DU CHEVALIER AU CYGNE.” Medium Ævum, vol. 36, no. 1, 1967, pp. 25–37. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43627310. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Barron, W. R. J. “VERSIONS AND TEXTS OF THE ‘NAISSANCE DU CHEVALIER AU CYGNE.’” Romania, vol. 89, no. 356 (4), 1968, pp. 481–538. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45040306. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Barto, P. S. “The Schwanritter-Sceaf Myth in ‘Perceval Le Gallois Ou Le Conte Du Graal.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 19, no. 2, 1920, pp. 190–200. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27700998. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

- Emplaincourt, Edmond A., and Jan A. Nelson. “‘LA GESTE DU CHEVALIER AU CYGNE’ : LA VERSION EN PROSE DE COPENHAGUE ET LA TRADITION DU PREMIER CYCLE DE LA CROISADE.” Romania, vol. 104, no. 415 (3), 1983, pp. 351–370. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45040923. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Smith, Hugh A. “SOME REMARKS ON A BERNE MANUSCRIPT OF THE ‘CHANSON DU CHEVALIER AU CYGNE ET DE GODEFROY DE BOUILLON.’” Romania, vol. 38, no. 149, 1909, pp. 120–128. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45043984. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

- Matthews, Alastair. The Medieval German Lohengrin: Narrative Poetics in the Story of the Swan Knight. NED - New edition ed., Boydell & Brewer, 2016. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt1k3s90m. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

- Todd, Henry Alfred. “Introduction.” PMLA, vol. 4, no. 3/4, 1889, pp. i-xv. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/456077. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Knight of the Swan. |

- Cheuelere Assigne Middle English from British Library MS Cotton Caligula A ii., Modern English translation

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.