Lamentation of Christ

The Lamentation of Christ[1] is a very common subject in Christian art from the High Middle Ages to the Baroque.[2] After Jesus was crucified, his body was removed from the cross and his friends mourned over his body. This event has been depicted by many different artists.

_adj.jpg.webp)

Lamentation works are very often included in cycles of the Life of Christ, and also form the subject of many individual works. One specific type of Lamentation depicts only Jesus' mother Mary cradling his body. These are known as Pietà (Italian for "pity").[3]

Development of the depiction

As the depiction of the Passion of Christ increased in complexity towards the end of the first millennium, a number of scenes were developed covering the period between the death of Jesus on the Cross and his being placed in his tomb. The accounts in the Canonical Gospels concentrate on the roles of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, but specifically mention Mary and Mary Magdalene as present. Scenes showing Joseph negotiating with Pontius Pilate for permission to take Christ's body are rare in art.[4]

The Deposition of Christ, where the body is being taken down from the cross, shown almost always in a vertical or diagonal position still off the ground, was the first scene to be developed, appearing first in late 9th century Byzantine art, and soon after in Ottonian miniatures.[5] The Bearing of the Body, showing Jesus' body being carried by Joseph, Nicodemus and sometimes others, initially was the image covering the whole period between Deposition and Entombment, and remained usual in the Byzantine world.

The laying-out of Jesus' body on a slab or bier, in Greek the Epitaphios, became an important subject in Byzantine art, with special types of cloth icon, the Epitaphios and the Antimension; Western equivalents in painting are called the Anointing of Christ.[6] The Entombment of Christ, showing the lowering of Christ's body into the tomb, was a Western innovation of the late 10th century; tombs cut horizontally into a rock face being unfamiliar in Western Europe, usually a stone sarcophagus or a tomb cut down into a flat rock surface is shown.

From these different images another type, the Lamentation itself, arose from the 11th century, always giving a more prominent position to Mary, who either holds the body, and later has it across her lap, or sometimes falls back in a state of collapse as Joseph and others hold the body. In a very early Byzantine depiction of the 11th century,[7] a scene of this type is placed just outside the mouth of the tomb, but around the same time other images place the scene at the foot of the empty cross - in effect relocating it in both time (to before the bearing, laying-out and anointing of the body) as well as space. This became the standard scene in Western Gothic art, and even when the cross is subsequently seen less often, the landscape background is usually retained. In Early Netherlandish painting of the 15th century the three crosses often appear in the background of the painting, a short distance from the scene.

Lamentations did not appear in art north of the Alps until the 14th century, but then became very popular there, and Northern versions further developed the centrality of Mary to the composition.[8] The typical position of Christ's body changes from being flat on the ground or slab, usually seen in profile across the centre of the work, to the upper torso being raised by Mary or others, and finally being held in a near-vertical position, seen frontally, or across Mary's lap. Mary Magdalene typically holds Jesus' feet, and Joseph is usually a bearded older man, often richly dressed. In fully populated Lamentations the figures shown with the body include The Three Marys, John the Apostle, Joseph and Nicodemus, and often others of both sexes, not to mention angels and donor portraits.[9]

Giotto di Bondone's famous depiction in the Scrovegni Chapel includes ten further female figures, who are not intended to be individualized as they have no halos. The subject became increasingly a separate devotional image, concentrating on Mary's grief for her son, with less narrative emphasis; the logical outcome of this trend was the Pietà, showing just these two figures, which was especially suitable for sculpture.

The Deposition of Christ and the Lamentation or Pietà form the 13th of the Stations of the Cross, one of Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, and a common component of cycles of the Life of the Virgin, all of which increased the frequency with which the scene was depicted, as series of works based on these devotional themes became popular.

It is not always possible to say clearly whether a particular image should be regarded as a Lamentation or one of the other related subjects discussed above, and museums and art historians are not always consistent in their naming. The famous Mantegna painting, clearly motivated by an interest in foreshortening, is essentially an Anointing, and many scenes, especially Italian Trecento ones and those after 1500, share characteristics of the Lamentation and the Entombment.[10]

Ambrosius Benson's 16th century Lamentation triptych was stolen from the Nájera (La Rioja) in 1913. It was later resold several times. The last time was a Sotheby's auction in 2008, where it was purchased by an anonymous buyer for 1.46 million euros.[11]

Gallery

Lamentation of Christ found in the Church of St. Panteleimon (Nerezi) in Macedonia. The fresco dates back to the 12th century.

Lamentation of Christ found in the Church of St. Panteleimon (Nerezi) in Macedonia. The fresco dates back to the 12th century. Lamentation by Andrea Mantegna. See above.

Lamentation by Andrea Mantegna. See above. A post-Byzantine (Cretan school) Epitaphios with influence from Western Lamentations, by Theophanes of Crete. 1st half of 16th century.

A post-Byzantine (Cretan school) Epitaphios with influence from Western Lamentations, by Theophanes of Crete. 1st half of 16th century. An individual Lamentation from the Rohan Hours. The grieving Virgin cannot be consoled by the Apostle John, who looks up in consternation at a saddened God.

An individual Lamentation from the Rohan Hours. The grieving Virgin cannot be consoled by the Apostle John, who looks up in consternation at a saddened God. Lamentation by Simon Marmion, with the three crosses high on the hill behind.

Lamentation by Simon Marmion, with the three crosses high on the hill behind. Lamentation of Christ, c. 1500, Albrecht Dürer, set at the foot of the cross.

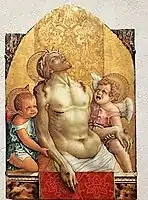

Lamentation of Christ, c. 1500, Albrecht Dürer, set at the foot of the cross. Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels, c. 1472, Carlo Crivelli, (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels, c. 1472, Carlo Crivelli, (Philadelphia Museum of Art) Lamentation by Dosso Dossi

Lamentation by Dosso Dossi Lamentation by Giovanni Bellini

Lamentation by Giovanni Bellini Lamentation of Christ by Mary and John by Peter Paul Rubens

Lamentation of Christ by Mary and John by Peter Paul Rubens Lamentation (Pietà), attributed to Petrus Christus

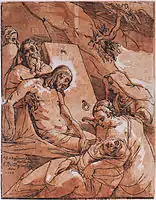

Lamentation (Pietà), attributed to Petrus Christus Lamentation or Entombment? Chiaroscuro woodcut by Andrea Andreani.

Lamentation or Entombment? Chiaroscuro woodcut by Andrea Andreani. A modern Lamentation, in Symbolist style by Bela Čikoš Sesija

A modern Lamentation, in Symbolist style by Bela Čikoš Sesija_-_Toronto.jpg.webp) A modern Orthodox icon of the 'Epitaphios Threnos' (Lamentation at the Tomb).

A modern Orthodox icon of the 'Epitaphios Threnos' (Lamentation at the Tomb).

Works with articles

- Lamentation of Christ (van der Weyden), 1460s

- Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints (Botticelli)

- Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Botticelli)

- Lamentation of Christ (Mantegna)

- Lamentation (Pietà) by Petrus Christus

- Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Perugino), 1495

- Lamentation of Christ (Dürer, Nuremberg), c. 1498

- Lamentation of Christ (Dürer, Munich), c. 1500

- Lamentation of Christ (Master of the Žebrák Lamentation of Christ), wood relief, c. 1510

- Lamentation (Gerard David), c. 1520

- Lamentation of Christ (Massys), 1511

- Lamentation of Christ, by Maarten van Heemskerck, c. 1540

Notes

- In addition to "Lamentation" and "Lamentation of Christ", the terms "Lamentation over the Dead Christ", "Lamentation over the Body of Christ", and Lamentation of the Virgin are also used.

- Schiller, 178

- In English usually used for images showing only Mary and Jesus, but in Italian used for Lamentations generally.

- Schiller, 164 lists examples

- Schiller, 164-5

- Schiller 168-72

- Schiller, 174

- Schiller, 176

- Schiller, 174-9

- Schiller, 178-9

- Lamentation of Christ Triptych Sold for 1.46 Million Euros

References

- G. Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972 (English trans. from German), Lund Humphries, London, pp. 164–181, figs 540-639, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lamentation of Christ. |