Leadhills

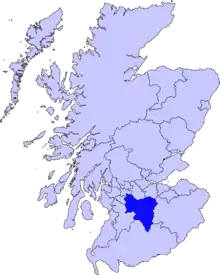

Leadhills, originally settled for the accommodation of miners, is a village in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, 5 3⁄4 miles (9.3 km) WSW of Elvanfoot. The population in 1901 was 835. It was originally known as Waterhead.[1]

It is the second highest village in Scotland, the highest being neighbouring Wanlockhead, 2 miles (3 kilometres) south.[2] It is near the source of Glengonnar Water, a tributary of the River Clyde.

Local attractions

Library

The Leadhills Miners' Library (also known as the Allan Ramsay Library or the Leadhills Reading Society), founded in 1741 by 21 miners, the local schoolteacher and the local minister, specifically to purchase a collection of books for its members’ mutual improvement[3][4] — its membership was not restricted to the miners; several non-miners, such as William Symington, John Brown (author of Rab and his Friends) and James Braid, were also full members — houses an extensive antiquarian book collection, local relics, mining records and minerals. The library is the oldest subscription library in the British Isles;[5] and is of significant historical and geological importance.

In the late eighteenth century, Peterkin observed the library had "as many valuable books as might be expected to be chosen by promiscuous readers"; he found its members to be "the best informed, and therefore the most reasonable common people that I know" (1799, p. 99); and, in 1823, "J", observing that "every miner can read, and most of them can write tolerably well", noted the library had around 1,200 volumes, all of which "have been entirely chosen by [the members] themselves", and that:

- As the miners work only six of the twenty-four hours in the mines, and as the barrenness of the soil affords little scope for agricultural pursuits, they have of course abundance of time for reading: and I believe they generally employ it to good purpose; for many of them can converse upon historical, scientific, and theological points so as to astonish a stranger; and even on political questions, they express their opinions with great acuteness and accuracy.[6]

Today, the library is owned and run by a registered charity, The Leadhills Heritage Trust and has full accreditation with Museums Galleries Scotland. It is open from Easter to September on weekends and bank holidays, between 2 pm and 5 pm.

Grouse moors

Grouse moors cover in excess of 11,000 acres (45 km2) around Leadhills. The area covered by the grouse moors has been identified as a location of several wildlife crimes involving raptor persecution.[7][8][9]

Golf course

Leadhills Golf Course, instituted in 1891, is the highest in Scotland. The nine-hole course offers a considerable challenge as the winds can be high and unpredictable as they are channelled between the hills.

Grave of John Taylor

The grave of John Taylor is also available to visit in the cemetery. Reputed to be 137 years of age at the time of his death, Taylor's grave (shared with his son, Robert) even attracted the attention of the BBC.[10]

Scots Mining Company House

The Scots Mining Company House was built in 1736 for James Stirling, the managing agent of the Scots Mining Company. It is attributed to the architect William Adam and is now a category A listed building.[11]

Leadhills and Wanlockhead Railway

The Leadhills and Wanlockhead Railway runs at weekends only and at Christmas sees the "Santa Express" which includes a ride on the train, a visit to Santa down the lead mine and a story read by "Mrs Kringle" in the Museum of Lead Mining, Wanlockhead. The Elvanfoot railway station was on the Caledonian Railway main line from Glasgow to the south. A branch from there ran through Leadhills to Wanlockhead and operated until 1939. Part of the route has been reused by the Leadhills & Wanlockhead Railway. The railway is 1,498 feet (457 m) above sea level.

Lowther Hills Ski Centre

The Lowther Hills is one of the birthplaces of Scottish winter sports. Curling in Leadhills can be traced back to 1784, when the Leadhills Curling Club –one of Scotland's first Curling societies- was created. The sport remained popular in the area until the 1930s, when the mines closed.

Since the 1920s skiing in the Leadhills area has been organised intermittently by a succession of local residents as well as several non-for-profit sports clubs. Lowther Hill, above the village, is home to the only ski area in the south of Scotland and Scotland's only community-owned ski centre. Operated by Lowther Hills Ski Club, the ski centre runs three ski lifts for beginners and intermediate skiers.[12]

Business

Leadhills is host to a number of small local businesses including shops and a hotel.

Geology

Gold, silver and lead

Silver and lead have been mined in Leadhills and at nearby Wanlockhead for many centuries, according to some authorities even in Roman days. Gold was discovered in the reign of James IV and, in those early days, it was so famous for its exceptionally pure gold that the general area was known as "God's Treasure House in Scotland". During the 16th century, before the alluvial gold deposits were exhausted, 300 men worked over three summers and took away some £100,000 of gold (perhaps £500 million today): "Between 1538 and 1542, the district produced 1163 grams of gold for a crown for King James V of Scotland and 992 grams for a crown for his queen. Much of the gold coinage of James V and Mary Queen of Scots was minted from Leadhills gold … No commercial gold mining appears to have taken place after 1620, but gold washing with a sluice box or pan was later to become a sometimes lucrative pastime of the lead miners" (Gillanders, 1981, pp. 235–236). Gold is still panned in the area with the correct licence.

Minerals

The minerals lanarkite, leadhillite, caledonite, susannite, plattnerite, scotlandite, macphersonite, chenite and mattheddleite were first found at Leadhills.[13] The area is renowned amongst mineralogists and geologists for its wide range of different mineral species found in the veins that lie deep within the (now abandoned) mine shafts;[14] with some now recognized as unique to the Leadhills area.[15]

Lanarkite

Lanarkite Leadhillite

Leadhillite Caledonite

Caledonite Susannite

Susannite Plattnerite (white crystals)

Plattnerite (white crystals) Macphersonite (yellow-brown crystal)

Macphersonite (yellow-brown crystal) Chenite

Chenite

Leadhills Supergroup

The village lends its name to the Leadhills Supergroup, one of the large geological features of the British Isles.

Mining

16th-century mining entrepreneurs working the area were landowners, goldsmiths and metallurgists, granted patents by the monarch and Privy Council. These included, Cornelius de Vos, George Douglas of Parkhead, John Acheson, Eustachius Roche, Thomas Foulis, George Bowes, Bevis Bulmer, and Stephen Atkinson.

Working conditions

The initial attraction of the Leadhills district was mining. On his visit to the mining area in 1772, the naturalist Thomas Pennant had remarked on its barren landscape:

- "Nothing can equal the barren and gloomy appearance of the country round [Leadhills]: neither tree nor shrub, nor verdure, nor picturesque rock, appear to amuse the eye…"[16]

Three years later, in 1776, artist William Gilpin found that, in relation to the working conditions, "the mines here, as in all mineral countries, are destructive of health", "you see an infirm frame, and squalid looks in most of the inhabitants".[17] and twelve years later, according to Rev. William Peterkin (1738-1792), the Minister at Leadhills (and member of its library) from 1785 until his death, the conditions of both the miners and the lead smelters were no better:

- The external appearance of Leadhills is ugly beyond description: rock, short heath, and barren [clay]. Every sort of vegetable is with difficulty raised and seldom comes to perfection. Spring water there is perhaps as fine as any in the world: but, the water below the smelting-[mills], the most dangerous. The lead before smelting is broke very small and washed from extraneous matter. It contains frequently arsenic, sulphur, zinc, &c. which poisons the water in which it is washed. Fowls of any kind will not live many days at Leadhills. They pick up arsenical particles with their food, which, soon kills, them. Horses, cows, dogs, cats, are liable to the lead-brash.[18] A cat, when seized with that distemper, springs like lightning through every corner of the house, falls into convulsions and dies. A dog falls into strong convulsions also but sometimes recovers. A cow grows perfectly mad in an instant and must be immediately killed. Fortunately, this distemper does not affect the human species.[19]

As Pennant had noted in 1772, the human counterpart of the animals' lead-brash was "mill-reek":

- The miners and smelters are subject here, as in other places, to the lead distemper, or mill-reek, as it is called here; which brings on palsies, and sometimes madness, terminating in death in about ten days.[20]

However, because lead was attracting such high prices during the American and Napoleonic Wars, and the domestic construction boom,[21] Leadhills became world-famous for its lead mines.[22]

In a paper reporting on the treatment of a particular case of hydrothorax, published in 1823, James Braid commented that, given all of the theoretically possible causes, with his numerous Leadhills hydrothorax patients, "[those who] have been exposed to breathe noxious or confined air" were by far the majority:[23]

- [At Leadhills] the miners must sometimes work in places where there is so little circulation of air, that their candles can scarcely burn; and I have almost invariably observed, that a continuance for any considerable length of time, (although in such situations they may only work three or four hours daily), brings on pneumonia in the young and plethoric, and hydrothorax in the old, if rather of spare habit of body; and if there should happen to be any healthy middle-aged men working as hand-neighbours to these others, although of course both must breath[e] the same impure air, these middle-aged men will remain free from any urgent complaint, till both their young and their aged neighbours are laid aside, perhaps never more to return. I became so fully convinced of this fact, as long ago to have induced me to recommend to the agents and overseers of this place, to avoid, as much as possible, putting thither very young or very old men into such situations.[24]

"Partnerships"

Like many metalliferous miners in other parts of the British Isles in the early 1800s, Leadhills miners did not work for daily wages;[25] in fact, Leadhills miners lived rent-free, working no more than six hours in any one day and, significantly, had no fixed working hours.

At Leadhills, each miner belonged to an autonomous group of up to 12 (a "partnership"),[26] who were paid collectively: on the basis of a contract (a "bargain") struck between one partner (the "taker") and the mining company, to perform a specific task for an agreed payment — in other words, the miners were paid for their results; not for the time they spent underground.[27] There were two types of bargain:

- "tut-" or "fathom work": work with no immediate return — such as sinking shafts, driving levels, making excavations, etc. — for a specified "length", usually 12, 15, or 20 fathoms, for a fixed amount.

- "tribute work": raising the ore to the surface — where the miners took all the ore from a specific location and were paid according to the total weight of the ore, at

The individual miner’s family also contributed; the sons worked on the uncovered washing platforms (exposed to the elements in all weathers) washing the impurities from the ore prior to smelting, and the wives and daughters spun wool and embroidered muslin for sale in Glasgow.

The partners supplied their own tools; and were responsible for their upkeep. Many important responsibilities lay with the partners; thus, for instance, only two overseers were needed to manage more than 200 Leadhills’ miners. In the absence of an overseer’s constant and immediate personal supervision, the partners were totally responsible for their collective work practices and occupational safety; thus, the partners, rather than overseers, would decide how to act against threats posed by subterranean water, loose ground, earth tremors, etc. However, with no overseer, there was also no oversight; and, often, hastily constructed passages/shafts were misaligned with those of other teams, affecting the structure of the entire mine — also, the disposal of waste and rubbish from one team’s work area often impeded the progress of another team (or teams).

Steam engines

Coal-fired steam engines, were an important part of the operation at Leadhills. Leadhills had three steam engines as early as 1778 (Smout, 1967, p. 106). In the winter of 1765, James Watt had been approached to design and build a steam engine for Leadhills that would raise water from 30 fathoms (approx. 55m.) below the surface. Watt did not get the contract (Hills, 1998).

belonging to Messrs Horner, Hurst, and Co. Leadhills, on the

forenoon of the 1st inst. occasioned by the air being rendered

impure from the smoke of a fire engine, placed about one

hundred feet underground.

As soon as the danger was ascertained. two miners and

the company‘s blacksmith descended to the relief of their

neighbours below, when unfortunately the two miners

perished in the humane attempt. The smith escaped but is

still dangerously ill. Many of the miners who were at work at

the time were violently affected, almost to suffocation, but are

now out of danger. We have since learned that in all seven

lives have been lost in this accident.

1817 mining accident

According to his later report (Braid, 1817), at 7:00 am on 1 March 1817, the mine's surgeon, James Braid, was called urgently to the mine to alleviate the distress of a number of miners who appeared to be suffocated.

It was later established that noxious fumes from the faulty chimney of a coal-fired steam engine,[30] operating deep within the mine,[31] had combined with a dense fog pervading the entire area. The contaminated air was lethal.

Two men, in the hope of finishing early, and contrary to established Leadhills custom, had entered the mine before 4 am;[32] another two, presumably from the same partnership, entered soon after. Reaching their work level (at 25 fathoms) the first two encountered the bad air. They persisted, thinking they could force their way through it, began to feel dizzy, collapsed, and eventually suffocated. The next two encountered a similar fate. The accident was not discovered until some time after 6 am; by which time all of the four men were dead.[33]

To aid those at the 25 fathom level, who were beginning to become violently affected by the fumes, a trap-door was opened to help clear the air; however, unfortunately, the noxious fumes descended rapidly, and another three men, at the 80 fathom level, suffocated. The other miners, many whom were affected to a considerable degree, were restored by Braid as they emerged from the mine.[34]

Cemetery

The cemetery at the northeast of the village features an unusual table-stone inscription (next to the southern wall) detailing, almost as an afterthought, 137 years as the age at death of John Taylor, the father of Robert Taylor, (then) overseer of the Scotch Mining Company.

Notable residents

Allan Ramsay, the poet, and William Symington (1763–1831), one of the earliest adaptors of the steam engine to the purposes of navigation, were born at Leadhills.

The famous mathematician James Stirling was employed by the Scots Mining Company at Leadhills from 1734 until 1770.[35] James Braid, the (later) discoverer of hypnotism, was surgeon to the Leadhills mining community and to Lord Hopetoun's lead and silver mines from early 1816 to late 1825.[36]

Climate

Leadhills experiences a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc). Due to its elevation and inland position, winters are colder and summers cooler than lower lying areas. In terms of the local climate profile, given its elevated position and latitude, Leadhills is amongst the coldest places in the British Isles. According to the most recent 30-year climate period of 1981-2010 Leadhills is the second coldest village in the UK (of those with weather stations) with an annual mean temperature of 6.76 °C (44.17 °F) making it slightly colder than the commonly regarded coldest settlement of Braemar, which had an annual average temperature of 6.81 °C (44.26 °F) in this period.[37] However, Leadhills' slightly more exposed and elevated location than Braemar results in absolute minima being higher than one might expect - the December absolute minimum of −15.0 °C (5.0 °F)[38] compares favourably to usually milder Glasgow Airport's absolute minimum of −20.0 °C (−4.0 °F).

Footnotes

- Sinclair, John (1799). The Statistical Account of Scotland: Drawn Up from the Communications of the Ministers of the Different Parishes. 21. Edinburgh: William Creech. p. 98.

- Phoebe Keane (17 April 2019). "Where is Scotland's highest village?". BBC. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- On his 1841 visit to Leadhills, the statistician and school inspector Joseph Fletcher was so impressed with the Leadhills’ Reading Society that he included its "Articles and Laws" in his report to the Children's Employment Commission (they appear at Fletcher, 1842, pp. 874-878).

- "The inhabitants [of Leadhills], though chiefly employed in the severe labour of mining, are an enlightened set of people, having a pretty extensive subscription library, and exhibiting a zeal in the acquisition of useful knowledge perfectly astonishing" (Chambers & Chambers (1844), p.701.

- Foster & Sheppard (1995), p.41.

- "J" (1823), p.27.

- BBC News: Making History (16 May 2017): Police investigate hen harrier shooting near Leadhills

- Carluke Gazette (26 June 2017): Police appeal on shooting of owl at Leadhills Estate

- RSPB Scotland (25 September 2018): Driven grouse moor licensing needed to help end the illegal persecution of birds

- BBC Radio 4: Making History (23 November 2004): John Taylor, the ancient lead miner - could he really have been 137?

- (Historic Environment Scotland & LB732)

- Lowther Hills Ski Club

- Livingstone, Alec (2002). Minerals of Scotland. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland. ISBN 978-1901663464.

- The mines, operated by the Hopetoun family since 1638, finally closed in the 1930s.

- In fact, "during the first quarter of the 19th century, the Leadhills and Wanlockhead mines were making a significant contribution to the early development of mineralogy" (Gillanders, 1981, p.236). The exceptional range and scope of the extremely rare mineralogical specimens were such that, "so well known had the minerals of Leadhills become during the 1820s that the Scots Mining Company had to make a regulation preventing the miners from disposing of specimens to the growing number of collectors" (p.237). The later routine use of dynamite, rather than gunpowder, "was particularly unfavourable to the collector as many hundreds of valuable specimens that might have been [otherwise] saved were blown to pieces" (p.238).

- Pennant (1774), p.129.

- Gilpin, 1789, II, p.76;

- Lead-brash: literally, "lead-sickness". It was a most horrible form of lead poisoning, and the term lead-brash specifically referred to a condition in animals.

- Peterkin, 1799, pp.98-99.

- Pennant (1774), p.130.

- At its peak (1809) lead was selling at £32 per ton (approx £21,000 in 2015 per 1,000kg). Yet, by 1827 the price had slumped to £12 per ton — due to the removal of import dues on foreign lead, and the significant expansion of Spanish lead production, due to the re-emergence of Spanish trade following the end of the Peninsular War (Smout, 1962, pp.152, 154).

- The mine operators paid one in every six bars of lead, as rent, to Lord Hopetoun; and the average number of bars produced was around 18,000 each year (Chambers & Chambers, "Leadhills", (1844), p.701).

- In his Treatise on Poisons (1832), Robert Christison defers to Braid’s occupational safety knowledge, and reports Braid's view that systematic ventilation (including high chimneys) in smelting workshops significantly reduces lead-poisoning (p.506). From personal contact ("for I am informed by Mr Braid"), he cites Braid as an authority when emphatically stating that, whilst lead miners are liable to all sorts of occupational disease, they do not get lead poisoning because "the metals are not poisonous until oxidated", and that only those exposed to the fumes of the smelting furnaces succumb. (Christison (p.496) was eager to correct the widely held (erroneous) notion that all workers at the lead mines – namely, both "those who dig and pulverise the ore" and "those who roast the ore" — were equally likely to succumb.)

- Braid, "Hydrothorax", (1832), p.550.

- Unless specified, the account that follows in this sub-section is taken from the extensive treatment of the miner’s earnings and working conditions at Leadhills in Chapter Four of Harvey (2000).

- Which meant that a group of twelve miners could work three shifts a day.

- Harvey (2000) states that "earnings [from these bargains] were subject to deductions for candles, powder, etc, and were paid infrequently, [with the miners often] requiring subsistence in the form of food, or cash, on credit".

- A bing was precisely eight cwt.; viz., approx. 406.5kg.

- Harvey (2000) observes that tontale bargains had two distinct advantages for a mining company: (i) "they avoided problems of estimating the value of poor quality ore", and (ii) "they also meant the smelters were prompted to work proficiently in the interests of their fellows".

- This was partly a quality control failure. High sulphur content coal should never be used underground. Sulphur, when heated, is converted into sulphurous acid (H2SO3): a colourless, irritating gas, with the peculiar suffocating odour of burning brimstone. When concentrated, it causes suffocation and, when greatly diluted, it severely irritates the mucous membranes, producing secondary effects that have every appearance of extreme alcohol intoxication.

- In 1829, William Watson, the surgeon at nearby Wanlockhead for more than 40 years, Watson (1829) reported the consequences of a steam-engine’s wooden chimney having caught on fire, and burning for more than 24 hours, at the lead mine at nearby Wanlockhead.

- The established custom was that miners began entering the mines at 6 am.

- In his (1817) paper, Braid noted that, because each miner fixed his own time for entering the mine and worked at the mine entirely without oversight, the first four deaths occurred because there was no one else there, in the mine, who could rescue them when they first experienced breathing difficulties (which would not have been so if they had entered, with other miners, at 6 am).

- On 17 March 1817, the Caledonian Mercury reported that "five of the seven miners who were suffocated by the smoke of the steam-engine at Leadhills, have left widows, and in all thirty fatherless children to deplore their loss".

- Whilst at Leadhills, Stirling published a paper on the ventilation of mines, based upon his experience and observations of the techniques of Venetian glassblowers: "A Description of a Machine to Blow Fire by the Fall of Water; By James Stirling, F. R. S.", Philosophical Transactions, Vol. 43, (1 January 1744), pp.315-317.

- According to "J" (1823) pp.27,29, as the appointed surgeon, Braid received a horse, a house, and a salary from The Scots Mining Company as well as "the gains of his practice".

- "Climatology maps". KNMI.

- "1961 minimum". KNMI.

References

- A.G.B. (Alexander Balloch Grosart), "A Trip to the Gold Regions of Scotland, Described in a letter to a Friend (Part I)", The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review, Vol.39, (May 1853), pp.459-468; "A Trip to the Gold Regions of Scotland, Described in a letter to a Friend (Part II)", The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review, Vol.39, (June 1853), pp.589-598.

- Anon, "Mean Temperature of Leadhills for Ten Years", The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, Vol.5, No.9, (July 1821), p.219.

- Braid, J., "Case of Reunion of a Separated Portion of the Finger. By Mr JAMES BRAID, Surgeon at Leadhills. Communicated by CHARLES ANDERSON, M.D. Leith", Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol.12, No.48, (1 October 1816), pp.428-429.

- Braid, J., "Account of the Fatal Accident which happened in the Leadhills Company's Mines, the 1st March, 1817. By Mr. James Braid, Surgeon, Leadhills. Read before the Wernerian Society 7th June", The Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany, Vol.79, (June 1817), pp.414-416.

- Braid, J., "Account of a Thunder Storm in the Neighbourhood of Leadhills, Lanarkshire; By Mr. James Braid, Surgeon at Leadhills. Read before the Wernerian Society 7th June", Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Vol.1, No.5, (August 1817), pp.471-472.

- Braid, J., "Observations on the Formation of the various Lead-Spars", pp.508-513 in Memoirs of the Wernerian Natural History Society, Vol.IV (For the years 1821-22-23), Part II, (Edinburgh), 1823.

- Braid, J., "Case of Hydrothorax, successfully treated by Blood-letting, with Observations on the Nature and Causes of the Disease. By James Braid, Corresponding Member of the Wernerian Society, Surgeon at Leadhills", Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol.19, No.77, (1 October 1823), pp.546-551.

- Brown, R., "The Mines and Minerals of Leadhills", Transactions of the Dumfries and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Vol.6, (1918), pp. 124–137.

- Brown, R., "More about the Mines and Minerals of Wanlockhead and Leadhills", Transactions of the Dumfries and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Vol.13, (1925), pp. 58–79.

- Chambers, R. & Chambers, W., The Gazetteer of Scotland, Volume I, Andrew Jack, (Edinburgh), 1844.

- Crawford, J.C. [1997], "Leadhills Library and a Wider World", Library Review, Vol.46, No.8, (1997), pp. 539–553. doi=10.1108/00242539710187876

- Christison, R., A Treatise on Poisons: In Relation to Medical Jurisprudence, Physiology, and the Practice of Physic (Second Edition), Adam Black, (Edinburgh), 1832.

- Crawford, J.C. [2002], "The Community Library in Scottish History", Journal of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, Vol.28, Nos.5/6, (October 2002), pp. 245–255. doi: 10.1177/034003520202800507

- Fletcher, J., "Evidence Collected by Joseph Fletcher, Esq.: Leadhills Mines", pp. 866–878 in Tooke, T., Children's Employment Commission: Appendix to First Report of the Commissioners (Mines), Part II: Reports and Evidence from Sub-Commissioners (Sessional no. 382), (London), 1842.

- Fletcher, J., "Report by Joseph Fletcher, Esq., on the Employment of Children and Young Persons in the Lead-Mines of the Counties of Lanark and Dumfries; and on the State, Condition, and Treatment of such Children and Young Persons", pp. 861–865 in Tooke, T., Children's Employment Commission: Appendix to First Report of the Commissioners (Mines), Part II: Reports and Evidence from Sub-Commissioners (Sessional no. 382), (London), 1842.

- Foster, J. & Sheppard, J., British Archives: A Guide to Archive Resources in the United Kingdom (Third Edition), Macmillan, (Basingstoke), 1995.

- Gillanders, R.J. [1981], "Famous Mining Localities: The Leadhills-Wanlockhead District, Scotland", The Mineralogical Record, Vol.12, No.4, (July–August 1981), pp. 235–250.

- Gilpin, W., Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, Made in the Year 1776, On Several Parts of Great Britain: Particularly the High-Lands of Scotland: Volume II, R. Blamire, (London), 1789.

- Harvey, W.S., "Pumping Engines at the Leadhills Mines", British Mining, No.19, (1980), pp.5-14.

- Harvey, W.S. [1994], "Pollution at Leadhills: Responses to Domestic and Industrial Pollution in a Mining Community", The Local Historian, Vol.24, No.3, (August 1994), pp. 130–138.

- Harvey, W.S., Lead and Labour: The Story of the Miners of Leadhills and Wanlockhead, 2000.

- Harvey, W.S. & Downes-Rose, G. [1985], "The First Steam Engine on the Leadhills Mines", British Mining, No.28, (1985), pp.46-47.

- Hills, R.L., "James Watt’s Steam Engine for the Leadhills Mines", Mining History, Vol.13, No.6, (Winter 1998), pp.25-28.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Scots Mining Company House... (Category A Listed Building) (LB732)". Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "J.", "Letter to the Editor (Short Account of the Miners at Leadhills and Wanlockhead)", The Christian Observer, Vol.23, No.1, (January 1823), pp.26-29.

- Jackaman, P., "The Company, the Common Man and the Library: Leadhills and Wanlockhead", Library Review, Vol.29, No.1, (1980), pp. 27–32. doi=10.1108/eb012702

- Kaufman, P., "Leadhills: Library of Diggers", Libri, Vol.7, No.1, (1967), pp. 13–20.

- Kaufman, P., "Leadhills: Library of Diggers", pp. 163–170 in Kaufman, P., Libraries and Their Users: Collected Papers in Library History, The Library Association, (London), 1969.

- Pennant, T., A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides; MDCCLXXII, Part I, John Monk, (Chester), 1774.

- Peterkin, W., "Additions to Volume IV, No.LXVI, page 505, Parish of Leadhills: Additional Communications Respecting Leadhills, by the Rev. William Peterkin, Minister of Ecclesmachan, deceased", pp.97-99 in Sinclair, J., The Statistical Account of Scotland, Drawn up from the Communications of the Ministers of the different Parishes, by Sir John Sinclair, Bart. Volume XXI, William Creech, (Edinburgh), 1799.

- Prevost, W.A.J., "Lord Hopetoun's Mine at Leadhills: Illustrated by David Allan and Paul Sanby", Transactions of the Dumfries and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Vol.54, (1979), pp. 85–89.

- Risse, G.B., "‘Mill Reek’ in Scotland: Construction and Management of Lead Poisoning", pp. 199–228 in Risse, G.B., New Medical Challenges During the Scottish Enlightenment, Rodopi, (Amsterdam), 2005.

- Smout, T. [1962], "The Lead Mines of Wanlockhead", Transactions of the Dumfries and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Vol. 39, (1962), pp. 144–158.

- Smout, T. [1967], "Lead-Mining in Scotland, 1650-1850", pp. 103–135 in Payne, P.L. (ed), Studies in Scottish Business History, Frank Cass & Co., (London), 1967.

- Watson, W., "Account of the Effects of the Accidental Inhalation of the Gas of Burning Coal in the Wanlockhead Mines", The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol.32, No.101, (1 October 1829), pp.345-347.

- Watson, W., "Observations on the Influence of Imperfect Supplies of Fresh Air, Long Continued, on the General Health", The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol.35, No.106, (1 January 1831), pp.89-92.

- Wilson, J., "An Account of the Disease called Mill-Reek by the Miners at Leadhills, in a Letter from Mr. James Wilson, Surgeon at Durrisdeer, to Alexander Monro", Essays and Observations, Physical and Literary (of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh), Vol.1, (1754), p.459-466.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leadhills. |

- Local information on Leadhills

- http://www.leadhills.com

- http://www.leadhillsonline.org.uk/

- http://www.lowtherhills.com - Lowther Hills Ski Centre

- Andrew, M. 2007, The Leadhills and Wanlockhead Railway (Online), Available from: "The Leadhills and Wanlockhead Railway" website

- Meadowfoot Cottage. Date Unknown, Leadhills (Online), Available from: "Leadhills" website

- Video and commentary on the Leadhills & Wanlockhead Railway.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Leadhills". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Leadhills". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.