Legends of Catherine the Great

During and after the reign of the flamboyant and powerful Empress Catherine II of Russia, whose long rule led to the modernization of the Russian Empire, many urban legends arose, some false and others based on true events, concerning her sexual behavior.

Catherine had 22 male lovers throughout her life, some of whom would reap political benefits from their relationship with her, and many of whom were relatively younger. In addition to her sexual relationships, her multiple illicit relationships with Russian nobles, and unfounded rumors that she liked to collect erotic furniture, and an atmosphere of palace intrigue cultivated by her son Paul I of Russia, led to negative portrayals of Catherine.

Some called her the "Messalina of the Neva", while others termed her a nymphomaniac.[1] The rumors even extended into the circumstances surrounding her death, with one tale claiming she died while having sexual relations with a horse, when she actually died from a stroke[2].

Personal life narratives

Rumors of Catherine's private life had a large basis in the fact that she took many young lovers, even in old age. (Lord Byron's Don Juan, around the age of twenty-two, becomes her lover after the siege of Ismail (1790), in a fiction written only about twenty-five years after Catherine's death in 1796.)[3] This practice was not unusual by the court standards of the day, nor was it unusual to use rumour and innuendo of sexual excess politically. One of her early lovers, Stanisław August Poniatowski, was later supported by her to become a king of Poland.[4]

One unfavorable rumor was that Alexander Dmitriev-Mamonov and her later lovers were chosen by Prince Potemkin himself, after the end of the long relationship Catherine had with Potemkin, where he, perhaps, was her morganatic husband. After Mamonov eloped from the 60-year-old Empress with a 16-year-old maid of honour and married her, the embittered Catherine reputedly revenged herself of her rival "by secretly sending policemen disguised as women to whip her in her husband's presence".[5] However, another account claims that there is no truth in this story.[6]

According to some contemporaries close to Catherine, Countess Praskovya Bruce was prized by her as "L'éprouveuse", or "tester of male capacity."[7] Every potential lover was to spend a night with Bruce before he was admitted into Catherine's personal apartments. Their friendship was cut short when Bruce was found "in an assignment" with Catherine's youthful lover, Rimsky-Korsakov, ancestor of the composer; they both later withdrew from the imperial court to Moscow.

In his memoirs Charles François Philibert Masson (1762-1807) wrote that Catherine had "two passions, which never left her but with her last breath: the love of man, which degenerated into licentiousness, and the love of glory, which sunk into vanity. By the first of these passions, she was never so far governed as to become a Messalina, but she often disgraced both her rank and sex: by the second, she was led to undertake many laudable projects, which were seldom completed, and to engage in unjust wars, from which she derived at least that kind of fame which never fails to accompany success".[8]

Death narratives

Several stories about the circumstances of her death at age 67 in 1796 originated in the years following her death. An urban legend claims that she died as a result of her attempting sexual intercourse with a stallion—the story holds that the harness holding the horse above her broke, and she was crushed.[9] The origin of this false account of her death is unknown. However, it most likely began due to unfounded bawdy tales. The fact that this particular urban legend did not even emerge until several decades after her death, and that the legend has no clear source, should make it clear that this is no more than an urban legend that managed to gain popularity.

Another story claiming that she died on the toilet when her seat broke under her is true only in small part; she did collapse in a bathroom from a stroke, but after that she died while being cared for in her bed. This tale was widely circulated and even jokingly referred to by Aleksandr Pushkin in one of his untitled poems. ("Наказ писала, флоты жгла, / И умерла, садясь на судно."—literal translation: "Decreed the orders, burned the fleets / And died boarding a vessel," the last line can also be translated as "And died sitting down on the toilet.") There existed also a version on alleged assassination, by spring blades hidden in a toilet seat.[4]

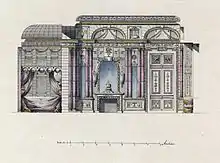

The erotic cabinet

An urban legend states that an erotic cabinet was ordered by Catherine the Great, and was adjacent to her suite of rooms in Gatchina. According to said urban legend; the furniture was highly eccentric with tables that had large penises for legs. Penises and vulvae were carved out on the furniture, the walls were covered in erotic art, statues of a naked man and woman inside, and some versions of the legend state that some erotic artifacts from Pompeii were even brought into Russia to augment this collection.

There are unconfirmed reports of photographs of this cabinet. The rooms and the furniture were allegedly seen in 1940 by two Wehrmacht officers during the Nazi Invasion of The Soviet Union, but even if that were true, the rooms and furniture seem to have vanished since then. The account says the Wehrmacht officers filed a report, but no report has ever been found, nor are any other records from anyone from before, during, or after the Second World War; other than the aforementioned legend. Also, the account says the rooms and furniture were seen in 1940, during the Nazi Invasion of The Soviet Union, but the invasion of The Soviet Union by Nazi Germany did not start in 1940, but on 22 June 1941. For this reason, historical experts challenge the veracity of such claims. But as all of these stories did not even originate until some years after Catherine the Great's death, it is most likely the cabinet never existed, and the whole story was simply fabricated as another bawdy tale.

Other narratives

- A long-surviving story about the Potemkin villages was false, even though it became eponymous. It states that Potemkin built fake settlements with hollow facades to fool Empress Catherine II during her visit to Crimea and New Russia, the territories Russia conquered under her reign. Modern historians, however, consider this scenario at best an exaggeration, and quite possibly simply a malicious rumor spread by Potemkin's opponents.[10]

- Not a native speaker of Russian, Catherine misspelled eщё ([jɪɕˈɕo] 'more'), written with three letters, as истчо ([ɪstˈtɕo]), consisting of five letters, and that allegedly gave rise to a popular Russian joke: how can five mistakes occur in a word of three letters? (The letter ё was not widely accepted until the 1940s).

- After Catherine granted to Kazan's Muslims the right to build mosques, the city's Christian leadership decided that mosques were being built too high—higher than churches. They sent a petition to Catherine asking her to prohibit the construction of high minarets. As the legend goes, Catherine replied that she was the tsarina of the Russian land and that the sky was beyond her jurisdiction.

- The Polish-Jewish religious leader Jacob Frank spread the rumour that his daughter Eve Frank was Catherine's illegitimate daughter.[11]

References

- General

- М. Евгеньева, "Любовники Екатерины." – Москва: Внешторгиздат, 1989 (in Russian, M. Yevgen'yeva, "Lovers of Catherine", Moscow, Vneshtorgizdat, 1989)

- Beccia, Carlyn "Raucous Royals" Houghton Mifflin, 2008

- Inline

- Longworth, Philip. The Three Empresses: Catherine I, Anne and Elizabeth of Russia. Constable Limited, 1972.

- Rounding, Virginia (2008). Catherine the Great: Love, Sex, and Power. Macmillan. p. 502. ISBN 978-0-312-37863-9.

- http://petercochran.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/don_juan_canto_9.pdf Lord Byron's Canto IX edited by Peter Cochran with his comments.

- Jan Larecki. Katarzyna Łóżkowa in: Polityka nr. 40 (2623)/2007, p. 85, (in Polish)

- John T. Alexander. Catherine the Great: Life and Legend. Oxford University Press, 1989. p. 222.

- Alexander 222.

- Arthur Asa Berger. The Art of the Seductress." iUniverse, 2001. p. 70.

- Secret Memoirs of the Court of St Petersburg by C.F.P. Masson (1800, translated from the French in 1895, I 88-9)

- Raucous Royals

- Adams, Cecil (2003). "Did "Potemkin villages" really exist?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- Frank, Eva article by Rachel Elior in the Encyclopedia Judaica.