Lemniscate of Bernoulli

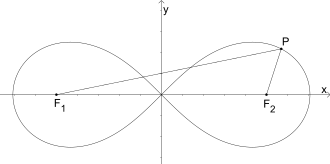

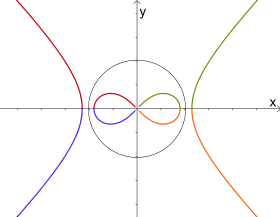

In geometry, the lemniscate of Bernoulli is a plane curve defined from two given points F1 and F2, known as foci, at distance 2c from each other as the locus of points P so that PF1·PF2 = c2. The curve has a shape similar to the numeral 8 and to the ∞ symbol. Its name is from lemniscatus, which is Latin for "decorated with hanging ribbons". It is a special case of the Cassini oval and is a rational algebraic curve of degree 4.

This lemniscate was first described in 1694 by Jakob Bernoulli as a modification of an ellipse, which is the locus of points for which the sum of the distances to each of two fixed focal points is a constant. A Cassini oval, by contrast, is the locus of points for which the product of these distances is constant. In the case where the curve passes through the point midway between the foci, the oval is a lemniscate of Bernoulli.

This curve can be obtained as the inverse transform of a hyperbola, with the inversion circle centered at the center of the hyperbola (bisector of its two foci). It may also be drawn by a mechanical linkage in the form of Watt's linkage, with the lengths of the three bars of the linkage and the distance between its endpoints chosen to form a crossed parallelogram.[1]

Equations

The equations can be stated in terms of the focal distance c or the half-width a of a lemniscate. These parameters are related as

- Its Cartesian equation is (up to translation and rotation):

- As a parametric equation:

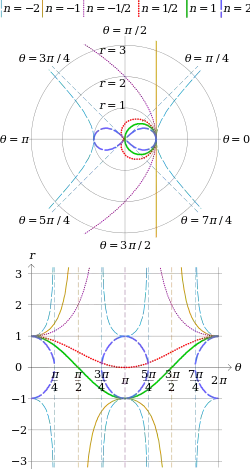

- In polar coordinates:

- Its equation in the complex plane is:

- In two-center bipolar coordinates:

- In rational polar coordinates:

Arc length and elliptic functions

The determination of the arc length of arcs of the lemniscate leads to elliptic integrals, as was discovered in the eighteenth century. Around 1800, the elliptic functions inverting those integrals were studied by C. F. Gauss (largely unpublished at the time, but allusions in the notes to his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae). The period lattices are of a very special form, being proportional to the Gaussian integers. For this reason the case of elliptic functions with complex multiplication by √−1 is called the lemniscatic case in some sources.

Using the elliptic integral

the formula of the arc length can be given as

- .

Angles

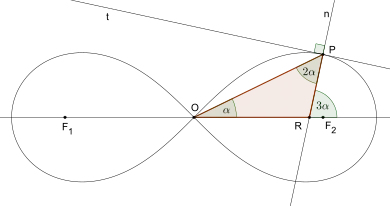

The following theorem about angles occurring in the lemniscate is due to German mathematician Gerhard Christoph Hermann Vechtmann, who described it 1843 in his dissertation on lemniscates.[2]

- F1 and F2 are the foci of the lemniscate, O is the midpoint of the line segment F1F2 and P is any point on the lemniscate outside the line connecting F1 and F2. The normal n of the lemniscate in P intersects the line connecting F1 and F2 in R. Now the interior angle of the triangle OPR at O is one third of the triangle's exterior angle at R. In addition the interior angle at P is twice the interior angle at O.

Further properties

- The lemniscate is symmetric to the line connecting its foci F1 and F2 and as well to the perpendicular bisector of the line segment F1F2.

- The lemniscate is symmetric to the midpoint of the line segment F1F2.

- The area enclosed by the lemniscate is 2a2.

- The lemniscate is the circle inversion of a hyperbola and vice versa.

- The two tangents at the midpoint O are orthogonal and each of them forms an angle of with line connecting F1 and F2.

- The planar cross-section of a standard torus tangent to its inner equator is a lemniscate.

Applications

Dynamics on this curve and its more generalized versions are studied in quasi-one-dimensional models.

See also

Notes

- Bryant, John; Sangwin, Christopher J. (2008), How round is your circle? Where Engineering and Mathematics Meet, Princeton University Press, pp. 58–59, ISBN 978-0-691-13118-4.

- Alexander Ostermann, Gerhard Wanner: Geometry by Its History. Springer, 2012, pp. 207-208

References

- J. Dennis Lawrence (1972). A catalog of special plane curves. Dover Publications. pp. 4–5, 121–123, 145, 151, 184. ISBN 0-486-60288-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lemniscate of Bernoulli. |