List of musical symbols

Musical symbols are marks and symbols used since about the 13th century in musical notation of musical scores. Some are used to notate pitch, tempo, metre, duration, and articulation of a note or a passage of music. In some cases, symbols provide information about the form of a piece (e.g., how many repeats of a section) or about how to play the note (e.g., with violin family instruments, a note may be bowed or plucked). Some symbols are instrument-specific notation giving the performer information about which finger, hand or foot to use.

Lines

|

Staff/Stave

The staff is the fundamental latticework of music notation, on which symbols are placed. The five staff lines and four intervening spaces correspond to pitches of the diatonic scale, while a clef determines the specific pitch which is meant by a given line or space. In British usage, the word "stave" is often used. |

|

Ledger or leger lines These extend the staff to pitches that fall above or below it. Such ledger lines are placed behind the noteheads, and extend a small distance to each side. Multiple ledger lines can be used when necessary to notate pitches even farther above or below the staff. |

|

Bar line These separate measures (see time signatures below for an explanation of measures). Also used for changes in time signature. Bar lines are extended to connect multiple staves in certain types of music, such as for keyboard or harp, and in conductor master scores, but such extensions are not used for other types of music, such as vocal scores. |

|

Double bar line, Double barline These separate two sections of music, or are placed before a change in key signature and/or time signature. |

|

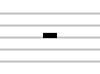

Bold double bar line, Bold double barline These indicate the conclusion of a movement or an entire composition. |

|

Dotted bar line, Dotted barline Subdivides long measures of complex meter into shorter segments for ease of reading, usually according to natural rhythmic subdivisions. |

| Bracket Connects two or more lines of music that sound simultaneously. In general contemporary usage the bracket usually connects the staves of separate instruments (e.g., flute and clarinet; two trumpets; etc.) or multiple vocal parts in a choir or ensemble, whereas the brace connects multiple parts for a single instrument (e.g., the right-hand and left-hand staves of a piano or harp part). | |

| Brace Connects two or more lines of music that are played simultaneously in piano, keyboard, harp, or some pitched percussion music, such as that for a glockenspiel, xylophone, marimba or other idiophone.[1] Depending on the instruments playing, the brace (occasionally called an accolade in some old texts) varies in design and style. |

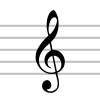

Clefs

Clefs define the pitch range, or tessitura, of the staff on which it is placed. A clef is usually the leftmost symbol on a staff. Additional clefs may appear in the middle of a staff to indicate a change in register for instruments with a wide range. In early music, clefs could be placed on any of several lines on a staff.

|

G clef (Treble clef) The centre of the spiral assigns the second line from the bottom to the pitch G above middle C.[2] The treble clef is the most commonly encountered clef in modern notation, and is used for most modern vocal music. Middle C is demarcated by the first ledger line below the staff here. |

|

C clef (Alto, and Tenor clefs) These clefs point to the line representing middle C. As illustrated here, it makes the center line on the staff middle C, and is referred to as the "alto clef". This clef is used in modern notation for the viola and some other instruments. While all clefs can be placed anywhere on the staff to indicate various tessitura, the C clef is most often considered a "movable" clef: it is frequently seen pointing instead to the fourth line (counting from the bottom) and called a "tenor clef". This clef is used very often in music written for bassoon, cello, trombone, and double bass; it replaces the bass clef when the number of ledger lines above the bass staff hinders easy reading. Until the classical era, the C clef was also frequently seen pointing to other lines, mostly in vocal music, but today this has been supplanted by the universal use of the treble and bass clefs. Modern editions of music from such periods generally transpose the original C clef parts to either treble (female voices), octave treble (tenors), or bass clef (tenors and basses). It can be occasionally seen in modern music on the third space (between the third and fourth lines), in which case it has the same function as an octave treble clef. This unusual practice runs the risk of misreading, however, because the traditional function of all clefs is to identify staff lines, not spaces. |

|

F clef (Bass clef) The line between the dots in this clef denotes F below middle C.[2] Positioned here, it makes the second line from the top of the staff F below middle C, and is called a "bass clef". This clef appears nearly as often as the treble clef, especially in choral music, where it represents the bass and baritone voices. Middle C is the first ledger line above the staff here. In old music, particularly vocal scores, this clef is sometimes encountered centered on the third staff line, in which position it is referred to as a baritone clef; this usage has essentially become obsolete. |

|

Neutral clef Used for pitchless instruments, such as some of those used for percussion. Each line can represent a specific percussion instrument within a set, such as in a drum set. Two different styles of neutral clefs are pictured here. It may also be drawn with a separate single-line staff for each untuned percussion instrument. |

|

Octave clef Treble and bass clefs can also be modified by octave numbers. An eight or fifteen above a clef raises the intended pitch range by one or two octaves respectively. Similarly, an eight or fifteen below a clef lowers the pitch range by one or two octaves respectively. A treble clef with an eight below is the most commonly used, typically used for guitar and similar instruments, as well as for tenor parts in choral music. |

|

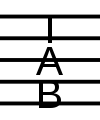

Tablature For stringed instruments, such as the guitar, it is possible to notate tablature in place of ordinary notes. In this case, a TAB sign is often written instead of a clef. The number of lines of the staff is not necessarily five: one line is used for each string of the instrument (so, for standard 6-stringed guitars, six lines would be used). Numbers on the lines show which fret to play the string on. This TAB sign, like the percussion clef, is not a clef in the true sense, but rather a symbol employed instead of a clef. Similarly, the horizontal lines do not constitute a staff in the usual sense, because the spaces between the lines in a tablature are never used. |

Notes and rests

Musical note and rest values do not necessarily have an absolute definition, but are proportional in duration to all other note and rest values. The whole note is the reference value, and the other notes are named (in American usage) in comparison; i.e., a quarter note is a quarter of the length of a whole note.

| Note | British name / American name | Rest |

|---|---|---|

|

Large (Latin: Maxima) / Octuple whole note[3] |  |

|

Long / Quadruple whole note[3] |  |

|

Breve / Double whole note |  |

|

Semibreve / Whole note |  |

|

Minim / Half note |  |

|

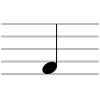

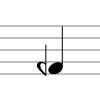

Crotchet / Quarter note[4][5] |  |

|

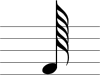

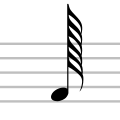

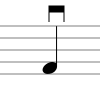

Quaver / Eighth note For notes of this length and shorter, the note has the same number of flags (or hooks) as the rest has branches. |

|

|

Semiquaver / Sixteenth note |  |

|

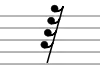

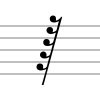

Demisemiquaver / Thirty-second note |  |

|

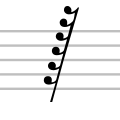

Hemidemisemiquaver / Sixty-fourth note |  |

|

Semihemidemisemiquaver / Quasihemidemisemiquaver / Hundred twenty-eighth note[6][7] |  |

|

Demisemihemidemisemiquaver / Two hundred fifty-sixth note[3] |  |

|

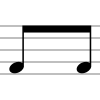

Beamed notes Beams connect eighth notes (quavers) and notes of shorter value and are equivalent in value to flags. In metered music, beams reflect the rhythmic grouping of notes. They may also group short phrases of notes of the same value, regardless of the meter; this is more common in ametrical passages. In older printings of vocal music, beams are often only used when several notes are to be sung on one syllable of the text – melismatic singing; modern notation encourages the use of beaming in a consistent manner with instrumental engraving, and the presence of beams or flags no longer informs the singer about the lyrics. In modern times, due to the body of music in which traditional metric states are not always assumed, beaming is at the discretion of composers and arrangers, who often use irregular beams to emphasize a particular rhythmic pattern. |

|

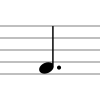

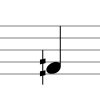

Dotted note Placing a dot to the right of a notehead lengthens the note's duration by one-half. Additional dots lengthen the previous dot instead of the original note, thus a note with one dot is one and one half its original value, a note with two dots is one and three quarters, a note with three dots is one and seven eighths, and so on. Rests can be dotted in the same manner as notes. In other words, n dots lengthen the note's or rest's original duration d to d × (2 − 2−n). |

|

Ghost note A note with a rhythmic value, but no discernible pitch when played. It is represented by a (saltire) cross (similar to the letter x) for a notehead instead of an oval. Composers will primarily use this notation to represent percussive pitches. This notation is also used in parts where spoken words are used. |

|

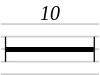

Multi-measure rest Indicates the number of measures in a resting part without a change in meter to conserve space and to simplify notation. Also called gathered rest or multi-bar rest. |

Breaks

|

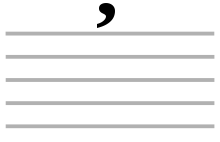

Breath mark This symbol tells the performer to take a breath for aerophones, for example the clarinet or trumpet (or make a slight pause for all other instruments). This pause usually does not affect the overall tempo. For chordophones like the violin or viola, or any other instruments that employ a bow, it indicates to lift the bow and play the next note with a downward (or upward, if marked) bow. |

|

Caesura A pause during which time is not counted. |

Accidentals and key signatures

Common accidentals

Accidentals modify the pitch of the notes that follow them on the same staff position within a measure, unless cancelled by an additional accidental.

|

Flat Lowers the pitch of a note by one semitone. |

|

Sharp Raises the pitch of a note by one semitone. |

|

Natural Renders null a previous accidental, or modifies the pitch of a sharp or flat as defined by the prevailing key signature (such as F-sharp in the key of G major, for example). |

|

Double flat Lowers the pitch of a note by two chromatic semitones. Usually used when the note to modify is already flatted by the key signature.[8] |

|

Double sharp Raises the pitch of a note by two chromatic semitones. Usually used when the note to modify is already sharpened by the key signature. |

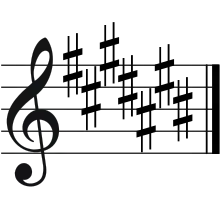

Key signatures

Key signatures define the prevailing key of the music that follows, thus avoiding the use of accidentals for many notes. If no key signature appears, the key is assumed to be C major/A minor, but can also signify a neutral key, employing individual accidentals as required for each note. The key signature examples shown here are described as they would appear on a treble staff.

|

Flat key signature Lowers by a semitone the pitch of notes on the corresponding line or space, and all octaves thereof, thus defining the prevailing major or minor key. Different keys are defined by the number of flats in the key signature, starting with the leftmost, i.e., B♭, and proceeding to the right; for example, if only the first two flats are used, the key is B♭ major/G minor, and all B's and E's are "flatted" (US) or "flattened" (UK), i.e., lowered to B♭ and E♭.[9] |

|

Sharp key signature Raises by a semitone the pitch of notes on the corresponding line or space, and all octaves thereof, thus defining the prevailing major or minor key. Different keys are defined by the number of sharps in the key signature, also proceeding from left to right; for example, if only the first four sharps are used, the key is E major/C♯ minor, and the corresponding pitches are raised. |

Quarter tones

There is no universally accepted notation for microtonal music, with varying systems being used depending on the situation. A common notation for quarter tones involves writing the fraction 1⁄4 next to an arrow pointing up or down. Below are other forms of notation:

|

Demiflat Lowers the pitch of a note by one quarter tone. (Another notation for the demiflat is a flat with a diagonal slash through its stem. In systems where pitches are divided into intervals smaller than a quarter tone, the slashed flat represents a lower note than the reversed flat.) |

|

Flat-and-a-half (sesquiflat) Lowers the pitch of a note by three quarter tones. As with a demiflat, a slashed double-flat symbol is also used. |

|

Demisharp Raises the pitch of a note by one quarter tone. |

|

Sharp-and-a-half (sesquisharp) Raises the pitch of a note by three quarter tones. Occasionally represented with two vertical and three diagonal bars instead. |

A symbol with one vertical and three diagonal bars indicates a sharp with some form of alternate tuning.

In 19 equal temperament, where a whole tone is divided into three steps instead of two, music is typically notated in a way that flats and sharps are not usually enharmonic (thus a C♯ represents a third of a step lower than D♭); this has the advantage of not requiring any nonstandard notation.

Time signatures

Time signatures define the meter of the music. Music is "marked off" in uniform sections called bars or measures, and time signatures establish the number of beats in each. This does not necessarily indicate which beats to emphasize, however, so a time signature that conveys information about the way the piece actually sounds is thus chosen. Time signatures tend to suggest prevailing groupings of beats or pulses rather than require beats or pulses.

|

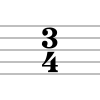

Specific time – simple time signatures The bottom number represents the note value of the basic pulse of the music (in this case the 4 represents the crotchet or quarter-note). The top number indicates how many of these note values appear in each measure. This example announces that each measure is the equivalent length of three crotchets (quarter-notes). For example, 3 4 is pronounced as "three-four time" or "three-quarter time". This figure is written without a dash between the top and bottom numbers, which is distinct from the way that a fraction is written. |

|

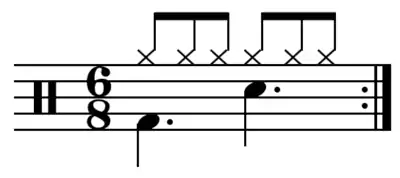

Specific time – compound time signatures The bottom number represents the note value of the subdivisions of the basic pulse of the music (in this case the 8 represents the quaver or eighth-note). The top number indicates how many of these subdivisions appear in each measure. Generally, each beat is composed of three subdivisions. To derive the unit of the basic pulse in compound meters, one must double this value and add a dot, and divide the top number by 3 to determine how many of these pulses there are in each measure. This example announces that each measure is the equivalent length of two dotted crotchets (dotted quarter-notes). This is pronounced as "Six-Eight Time". |

|

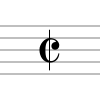

Common time This symbol represents 4 4 time. It derives from the broken circle that represented "imperfect" duple meter in fourteenth-century mensural time signatures. |

|

Alla breve or Cut time This symbol represents 2 2 time, indicating two minim (or half-note) beats per measure. Here, a crotchet (or quarter note) would get half a beat. |

|

Metronome mark Written at the start of a score, and at any significant change of tempo, this symbol precisely defines the tempo of the music by assigning absolute durations to all note values within the score. In this particular example, the performer is told that 120 crotchets, or quarter notes, fit into one minute of time. Many publishers precede the marking with letters "M.M.", referring to Maelzel's Metronome. This is also known as "120 beats per minute". |

Note relationships

|

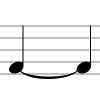

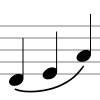

Tie Indicates that the two (or more) notes joined together are to be played as one note with the time values added together. To be a tie, the notes must be identical – that is, they must be on the same line or the same space. Otherwise, it is a slur (see below). |

|

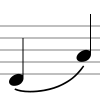

Slur Indicates to play two or more notes in one physical stroke on bowed chordophones, one uninterrupted breath on aerophones, or (on all other instruments like the pitched percussion instruments) connected into a phrase, as though a singer were to sing them in a single breath. In certain contexts, a slur may only indicate to play the notes legato. In this case, rearticulation is permitted. Slurs and ties are similar in appearance. A tie is distinguishable because it always joins two immediately adjacent notes of the same pitch, whereas a slur may join any number of notes of varying pitches. In vocal music a slur normally indicates that notes grouped together by the slur should be sung to a single syllable. A phrase mark (or less commonly, ligature) is a mark that is visually identical to a slur, but connects a passage of music over several measures. A phrase mark indicates a musical phrase and may not necessarily require that the music be slurred. |

|

Glissando or Portamento A continuous, unbroken glide from one note to the next that includes the pitches between. Some instruments, such as the trombone, timpani, non-fretted string instruments like the cello, electronic instruments, and the human voice can make this glide continuously (portamento), while other instruments such as the piano or mallet instruments blur the discrete pitches between the start and end notes to mimic a continuous slide (glissando). |

|

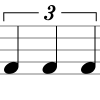

Tuplet A number of notes of irregular duration are performed within the duration of a given number of notes of regular time value; e.g., five notes played in the normal duration of four notes; seven notes played in the normal duration of two; three notes played in the normal duration of four. Tuplets are named according to the number of irregular notes; e.g., duplets, triplets, quadruplets, etc. |

|

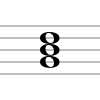

Chord Several notes sounded simultaneously ("solid" or "block"), or in succession ("broken"). Two-note chords are called a dyad or an interval; three-note chords built from generic third intervals are called triads. A chord may contain any number of notes. |

|

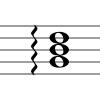

Arpeggiated chord A chord with notes played in rapid succession, usually ascending, each note being sustained as the others are played. It is also called a "broken chord" or "rolled chord". |

Dynamics

Dynamics are indicators of the relative intensity or volume of a musical line.

| Pianississimo[D 1] Extremely soft. Very infrequently does one see softer dynamics than this, which are specified with additional ps. | |

| Pianissimo Very soft. Usually the softest indication in a piece of music, though softer dynamics are often specified with additional ps. | |

| Piano Soft; louder than pianissimo. | |

| Mezzo piano Moderately soft; louder than piano. | |

| Mezzo forte Moderately loud; softer than forte. If no dynamic appears, mezzo-forte is assumed to be the prevailing dynamic level. | |

| Forte Loud. Used as often as piano to indicate contrast. | |

| Fortissimo Very loud. Usually the loudest indication in a piece, though louder dynamics are often specified with additional fs (such as fortississimo – seen below). | |

| Fortississimo[D 1] Extremely loud. Very infrequently does one see louder dynamics than this, which are specified with additional fs. | |

| Sforzando Literally "forced", denotes an abrupt, fierce accent on a single sound or chord. When written out in full, it applies to the sequence of sounds or chords under or over which it is placed. | |

|

Crescendo A gradual increase in volume. Can be extended under many notes to indicate that the volume steadily increases during the passage. |

|

Diminuendo Also decrescendo A gradual decrease in volume. Can be extended in the same manner as crescendo. |

- Dynamics with 3 letters (i.e., ppp and fff) are often referred to by adding an extra "iss" (pianissimo to pianississimo). This is improper Italian and would translate literally to "softestest" in English, but acceptable as a musical term; such a dynamic can also be described as molto pianissimo, piano pianissimo or molto fortissimo and forte fortissimo in somewhat more proper Italian.

Other commonly used dynamics build upon these values. For example, "pianississimo" (represented as ppp) means "so softly as to be almost inaudible", and "fortississimo" (fff) correspondingly refers to "extremely loud". Dynamics are relative, and the meaning of each level is at the discretion of the performer or, in the case of ensembles, the conductor. However, modern legislation to curb high noise levels in the workplace in an effort to prevent damage to musicians' hearing has posed a challenge to the interpretation of very loud dynamics in some large orchestral works, as noise levels within the orchestra itself can easily exceed safe levels when all instruments are playing at full volume.[10]

A small s in front of the dynamic notations means subito (meaning "suddenly" in Italian), and means that the dynamic is to change to the new notation rapidly. Subito is commonly used with sforzandos, but can appear with all other dynamic notations, most commonly as sff (subitofortissimo) or spp (subitopianissimo).

|

Forte-piano A section of music in which the music should initially be played loudly (forte), then immediately softly (piano). |

Another value that rarely appears is niente or n, which means "nothing". This may be used at the end of a diminuendo to indicate "fade out to nothing".

Articulation marks

Articulations (or accents) specify how to perform individual notes within a phrase or passage. They can be fine-tuned by combining more than one such symbol over or under a note. They may also appear in conjunction with phrasing marks listed above.

|

Staccatissimo or Spiccato Indicates a longer silence after the note (as described above), making the note very short. Usually applied to quarter notes or shorter. (In the past, this marking's meaning was more ambiguous: it sometimes was used interchangeably with staccato, and sometimes indicated an accent and not staccato. These usages are now almost defunct, but still appear in some scores.) In string instruments this indicates a bowing technique in which the bow bounces lightly upon the string. |

|

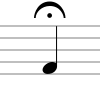

Staccato This indicates the musician should play the note shorter than notated, usually half the value; the rest of the metric value is then silent. Staccato marks may appear on notes of any value, shortening their performed duration without speeding the music itself. |

|

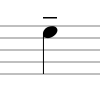

Tenuto This symbol indicates play the note at its full value, or slightly longer. It can also indicate a degree of emphasis, especially when combined with dynamic markings to indicate a change in loudness, or combined with a staccato dot to indicate a slight detachment (portato or mezzo staccato). |

|

Fermata or Pause A note, chord, or rest sustained longer than its customary value. Usually appears over all parts at the same metrical location in a piece, to show a halt in tempo. It can be placed above or below the note. The fermata is held for as long as the performer or conductor desires, but is often set as twice the original value of the designated notes. |

|

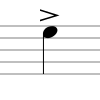

Accent Play the note louder, or with a harder attack than surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. |

|

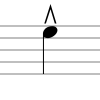

Marcato Play the note somewhat louder or more forcefully than a note with a regular accent mark (open horizontal wedge). In organ notation, this means play a pedal note with the toe. Above the note, use the right foot; below the note, use the left foot. |

Ornaments

Ornaments modify the pitch pattern of individual notes.

|

Trill A rapid alternation between the specified note and the next higher note (determined by key signature) within its duration, also called a "shake". When followed by a wavy horizontal line, this symbol indicates an extended, or running, trill. In modern music the trill begins on the main note and ends with the lower auxiliary note then the main note, which requires a triplet immediately before the turn. In music up to the time of Haydn or Mozart the trill begins on the upper auxiliary note and there is no triplet.[11] In percussion notation, a trill is sometimes used to indicate a tremolo. In French baroque notation, the trill, or tremblement, was notated as a small cross above or beside the note. |

|

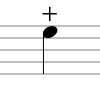

Upper mordent Rapidly play the principal note, the next higher note (according to key signature) then return to the principal note for the remaining duration. In most music, the mordent begins on the auxiliary note, and the alternation between the two notes may be extended. In handbells, this symbol is a "shake" and indicates the rapid shaking of the bells for the duration of the note. |

|

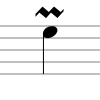

Lower mordent (inverted) Rapidly play the principal note, the note below it, then return to the principal note for the remaining duration. In much music, the mordent begins on the auxiliary note, and the alternation between the two notes may be extended. |

.png.webp)  |

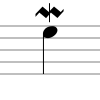

Gruppetto or Turn When placed directly above the note, the turn (also known as a gruppetto) indicates a sequence of upper auxiliary note, principal note, lower auxiliary note, and a return to the principal note. When placed to the right of the note, the principal note is played first, followed by the above pattern. Placing a vertical line through the turn symbol or inverting it, it indicates an inverted turn, in which the order of the auxiliary notes is reversed. |

|

Appoggiatura The first half of the principal note's duration has the pitch of the grace note (the first two-thirds if the principal note is a dotted note). |

|

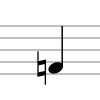

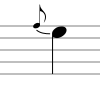

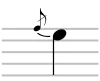

Acciaccatura The acciaccatura is of very brief duration, as though brushed on the way to the principal note, which receives virtually all of its notated duration. In percussion notation, the acciaccatura symbol denotes the flam rudiment, the miniature note still positioned behind the main note but on the same line or space of the staff. The flam note is usually played just before the natural durational subdivision the main note is played on, with the timing and duration of the main note remaining unchanged. Also known by the English translation of the Italian term, crushed note, and in German as Zusammenschlag (simultaneous stroke). |

Octave signs

|

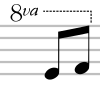

Ottava 8va (pronounced ottava alta) is placed above the staff (as shown) to tell the musician to play the passage one octave higher. When this sign (or in recent notation practice, an 8vb – both signs reading ottava bassa) is placed below the staff, it indicates to play the passage one octave lower.[12][13] |

|

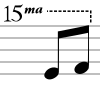

Quindicesima The 15ma sign is placed above the staff (as shown) to mean "play the passage two octaves higher". A 15ma sign below the staff indicates "play the passage two octaves lower". |

8va and 15ma are sometimes abbreviated further to 8 and 15. When they appear below the staff, the word bassa is sometimes added.

Repetition and codas

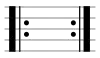

|

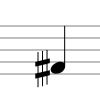

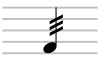

Tremolo A rapidly repeated note. If the tremolo is between two notes, then they are played in rapid alternation. The number of slashes through the stem (or number of diagonal bars between two notes) indicates the frequency to repeat (or alternate) the note. As shown here, the note is to be repeated at a demisemiquaver (thirty-second note) rate, but it is a common convention for three slashes to be interpreted as "as fast as possible", or at any rate at a speed to be left to the player's judgment. In percussion notation, tremolos indicate rolls, diddles, and drags. Typically, a single tremolo line on a sufficiently short note (such as a sixteenth) is played as a drag, and a combination of three stem and tremolo lines indicates a double-stroke roll (or a single-stroke roll, in the case of timpani, mallet percussion and some untuned percussion instruments such as triangle and bass drum) for a period equivalent to the duration of the note. In other cases, the interpretation of tremolos is highly variable, and should be examined by the director and performers. The tremolo symbol also represents flutter-tonguing. |

|

Repeat signs Enclose a passage that is to be played more than once. If there is no left repeat sign, the right repeat sign sends the performer back to the start of the piece or the nearest double bar. |

|

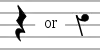

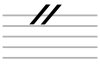

Simile marks Denote that preceding groups of beats or measures are to be repeated. In the examples here, the first usually means to repeat the previous measure, and the second usually means to repeat the previous two measures. |

|

Volta brackets (1st and 2nd endings, or 1st- and 2nd-time bars) A repeated passage is to be played with different endings on different playings; although two endings are most common, it is possible to have more than two endings (1st, 2nd, 3rd ...). |

|

Da capo (lit. "From top") Tells the performer to repeat playing of the music from its beginning. This is usually followed by al fine (lit. "to the end"), which means to repeat to the word fine and stop, or al coda (lit. "to the coda (sign)"), which means repeat to the coda sign and then jump forward. |

|

Dal segno (lit. "From the sign") Tells the performer to repeat playing of the music starting at the nearest segno. This is followed by al fine or al coda just as with da capo. |

|

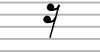

Segno Mark used with dal segno. |

|

Coda Indicates a forward jump in the music to its ending passage, marked with the same sign. Only used after playing through a D.S. al coda (Dal segno al coda) or D.C. al coda (Da capo al coda). |

Instrument-specific notation

Bowed string instruments

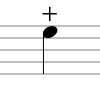

|

Left-hand pizzicato or Stopped note A note on a stringed instrument where the string is plucked with the left hand (the hand that usually stops the strings) rather than bowed. On the horn, this accent indicates a "stopped note" (a note played with the stopping hand shoved further into the bell of the horn). In percussion this notation denotes, among many other specific uses, to close the hi-hat by pressing the pedal, or that an instrument is to be "choked" (muted with the hand). |

|

Snap pizzicato On a stringed instrument, a note played by stretching a string away from the frame of the instrument and letting it go, making it "snap" against the frame. Also known as a Bartók pizzicato. |

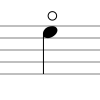

|

Natural harmonic or Open note On a stringed instrument, this means to play a natural harmonic (also called flageolet). Sometimes, it also denotes that the note to be played is an open string. On a valved brass instrument, it means to play the note "open" (without lowering any valve, or without mute). In organ notation, this means to play a pedal note with the heel (above the note, use the right foot; below the note, use the left foot). In percussion notation this denotes, among many other specific uses, to open the hi-hat by releasing the pedal, or allow an instrument to ring. |

|

Up bow or Sull'arco On a bowed string instrument, the note is played while drawing the bow upward. On a plucked string instrument played with a plectrum or pick (such as a guitar played pickstyle or a mandolin), the note is played with an upstroke. |

|

Down bow or Giù arco In contrast to the up bow, here the bow is drawn downward to create sound. On a plucked string instrument played with a plectrum or pick (such as a guitar played pickstyle or a mandolin), the note is played with a downstroke. |

Guitar

The guitar has a fingerpicking notation system derived from the names of the fingers in Spanish or Latin. They are written above, below, or beside the note to which they are attached. They read as follows:

| Symbol | Spanish | Italian | Latin | English | French |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | pulgar | pollice | pollex | thumb | pouce |

| i | índice | indice | index | index | index |

| m | medio | medio | media | middle | majeur ou médius |

| a | anular | anulare | anularis | ring | annulaire |

| c, x, e, q | meñique | mignolo | minimus | little | auriculaire |

Pedal marks

Pedal marks appear in music for instruments with sustain pedals, such as the piano, vibraphone and chimes.

| Engage pedal Tells the player to put the sustain pedal down. | |

| Release pedal Tells the player to let the sustain pedal up. | |

|

Variable pedal mark More accurately indicates the precise use of the sustain pedal. The extended lower line tells the player to keep the sustain pedal depressed for all notes below which it appears. The ∧ shape indicates the pedal is to be momentarily released, then depressed again. |

| Con sordino (or con sordini), una corda Tells the player to put the soft pedal down or, for other instruments, apply the mute. | |

| Senza sordino (or senza sordini), tre corde or tutte le corde Tells the player to let the soft pedal up or, for other instruments, remove the mute. |

Other piano notation

| left hand | right hand | |

|---|---|---|

| English | l.h. | r.h. |

| left hand | right hand | |

| German | l.H. | r.H. |

| linke Hand | rechte Hand | |

| French | m.g. | m.d. |

| main gauche | main droite | |

| Italian | m.s. | m.d. |

| mano sinistra | mano destra | |

| Spanish | m.i. | m.d. |

| mano izquierda | mano derecha |

| 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Finger identifications: 1 = thumb 2 = index 3 = middle 4 = ring 5 = little |

Old (pre-1940) tutors published in the UK may use "English fingering". + for thumb, then 1 (index), 2 (middle), 3 (ring) and 4 (little).[14]

Other stringed instruments

(With the exception of harp)

| 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 | Finger identifications: 0 = open string (no finger used) 1 = index 2 = middle 3 = ring 4 = little The thumb is also used by the cello and bass, usually denoted by a T or + |

See also Fingerstyle guitar#Notation.

Four-mallet percussion

| 1, 2, 3, 4 | Mallet identifications: 1 = Far left mallet 2 = Inner-left mallet 3 = Inner-right mallet 4 = Far right mallet |

| Some systems reverse the numbers (e.g., 4 = Far-left mallet, 3 = Inner-left mallet, etc.) |

Six-mallet percussion

| 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | Mallet identifications: 1 = Far-left mallet 2 = Middle-left mallet 3 = Inner-left mallet 4 = Inner-right mallet 5 = Middle-right mallet 6 = Far-right mallet |

Numbers for six-mallet percussion may be reversed as well.[15]

See also

References

- "Music Notation and Engraving – Braces and Bracket, Colorado College Music Department

- Gerou, Tom; Lusk, Linda (1996). Essential Dictionary of Music Notation. Alfred Music. p. 49. ISBN 0-88284-768-6.

- "UNLP at the C@merata Task: Question Answering on Musical Scores ACM" (PDF). Csee.essex.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- Examples of the older rest symbol are found in the work of English music publishers up to the 20th century, e.g., W. A. Mozart Requiem Mass, vocal score ed. W. T. Best, pub. London: Novello & Co. Ltd. 1879.

- Rudiments and Theory of Music Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, London 1958. I,33 and III,25. The former shows both rest forms without distinction, the latter the "old" form only. The book was the standard theory manual in the UK up until at least 1975. The "old" form was taught as a manuscript variant of the printed form.

- Miller, RJ (2015). Contemporary Orchestration: A Practical Guide to Instruments, Ensembles, and Musicians. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-415-74190-3.

- Haas, David (2011). "Shostakovich's Second Piano Sonata: A Composition Recital in Three Styles". In Fairclough, Pauline; Fanning, David (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shostakovich. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–114. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521842204.006. ISBN 978-1-139-00195-3.

The listener is right to suspect a Baroque reference when a double-dotted rhythmic gesture and semihemidemisemiquaver triplets appear to ornament the theme.

(p. 112) - "Sharps, Flats, Double Sharps, Double Flats in Music Theory", musictheorysite.com

- Rudiments and Theory of Music Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, London 1958. I,24 "at least one note has to be sharpened or flattened"

- "No Fortissimo? Symphony Told to Keep It Down" by Sarah Lyall, The New York Times (20 April 2008)

- Rudiments and Theory of Music Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, London 1958. V,29

- George Heussenstamm, The Norton Manual of Music Notation (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company), p. 16

- Anthony Donato, Preparing Music Manuscript (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall), pp. 42-43

- "Scales-continental/ English Fingering". The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. 20 December 2004. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Paterson, Robert (2004). Sounds That Resonate: Selected Developments in Western Bar Percussion During the Twentieth Century. Cornell University: UMI Dissertation Services No. 3114502. p. 182.

External links

- Comprehensive list of music symbols fonts

- Music theory & history (Dolmetsch Online)

- Dictionary of musical symbols (Dolmetsch Online)

- Sight reading tutorial with symbol variations Amy Appleby