Lithuania–Poland border

The current Lithuania–Poland border has existed since the re-establishment of the independence of Lithuania on March 11, 1990. Until then the identical border was between Poland and the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union. The length of the border is 104 kilometres (65 mi).[1][2] It runs from the Lithuania–Poland–Russia tripoint southeast to the Belarus–Lithuania–Poland tripoint.

It is the only land border that the European Union- and NATO-member Baltic states share with a country that is not a member of the Russian-aligned Commonwealth of Independent States.[3]

History

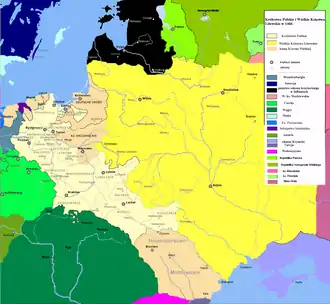

The current Lithuania–Poland border has existed since the re-establishment of the independence of Lithuania on March 11, 1990.[4] That border was established in the aftermath of World War II. Until then the identical border was between Poland and Lithuanian SSR of the Soviet Union.[5][6] A different border existed between the Second Polish Republic and Lithuania in the period of 1918–1939. Following the Polish–Lithuanian border conflict, from 1922 onward it was stable, and had a length of 521 km.[7][8] During the partitions of Poland era, there were borders between the Congress Poland (Augustów Voivodeship) and Lithuanian lands of the Russian Empire (Kovno Governorate and Vilna Governorate). From the Union of Lublin (1569) to the partitions, there was no Polish-Lithuanian border, as both countries were a part of a single federated entity, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[9] In medieval times, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania shared yet another border.[10]

Lithuania and Poland joined the Schengen Area in 2007. This meant that all passport checks were removed along the border in December 2007.

Military significance

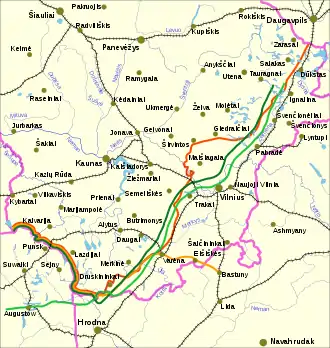

To the military planners of NATO, the border area is known as the Suwalki gap (named after the nearby town of Suwałki), because it represents a tough-to-defend flat narrow piece of land, a gap, that is between Belarus and Russia's Kaliningrad exclave and that connects the NATO-member Baltic States to Poland and the rest of NATO.[11] This view was reflected in a 2017 NATO exercise, which for the first time focused on defense of the gap from a possible Russian attack.[12]

Former border crossings

In the period 1991–2007, there were three road and one rail border crossing between Poland and Lithuania.[13]

On May 1, 2004, when both Poland and Lithuania joined the European Union, this border became an internal border of the European Union.[14] On 21 December 2007, Poland and Lithuania acceded to the Schengen Agreement.[15] After this, crossing the border became easier, as EU internal borders are open to all traffic with little need for control. There are still, however, occasional customs and police controls against smuggling of restricted goods, which however affect only about 1% of travelers.[16][17][18]

Road

Rail

Gallery

Map of Poland from the early 11th century shows Polish and Lithuanian lands separated by Old Prussian and Kievan Rus' territories

Map of Poland from the early 11th century shows Polish and Lithuanian lands separated by Old Prussian and Kievan Rus' territories.png.webp) Map of Poland in the first half of the 13th century, shows a border between Duchy of Masovia and Lithuania

Map of Poland in the first half of the 13th century, shows a border between Duchy of Masovia and Lithuania.png.webp) Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1275–1300, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border

Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1275–1300, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1333–1370, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border

Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1333–1370, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1370–1382, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border

Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1370–1382, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1386–1434, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border

Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1386–1434, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1466, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border

Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1466, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1526, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border

Map of Poland and Lithuania around 1526, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border Map of Polish-Lithuania Commonwealth after its formation in 1569, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border. Ukrainian territories were transferred under the administrative control of the Crown of Poland.

Map of Polish-Lithuania Commonwealth after its formation in 1569, with visible Polish–Lithuanian border. Ukrainian territories were transferred under the administrative control of the Crown of Poland. Map of Lithuania around 1867–1914, with visible Polish–Russian border (Lithuania did not exist at that time)

Map of Lithuania around 1867–1914, with visible Polish–Russian border (Lithuania did not exist at that time) Polish–Lithuanian border around 1918–1939

Polish–Lithuanian border around 1918–1939

References

- "Warunki Naturalne I Ochrona Środowiska" [Environment and Environmental Protection]. Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2013 [Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland 2013]. Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski = Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland (in Polish and English). Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2013. p. 26. ISSN 1640-3630.

- "Archived copy" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2015-03-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Page gives Polish PWN Encyklopedia as reference.

- Vladimir Shlapentokh (1 January 2001). The Legacy of History in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. M.E. Sharpe. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-7656-1398-1.

- "LR AT AKTO Dėl Lietuvos nepriklausomos valstybės atstatymo signatarai". Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas.

- Peter Andreas; Timothy Snyder (1 January 2000). The Wall Around the West: State Borders and Immigration Controls in North America and Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-7425-0178-2.

- Yaël Ronen (19 May 2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-139-49617-9.

- Polska w cyfrach [in:] E. Romer Atlas Polski współczesnej, 1928.

- Michael Brecher (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. pp. 252–255. ISBN 0-472-10806-9.

- Halina Lerski (19 January 1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. ABC-CLIO. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-313-03456-5.

- Stephen R. Burant and Voytek Zubek, Eastern Europe's Old Memories and New Realities: Resurrecting the Polish–Lithuanian Union, East European Politics and Societies 1993; 7; 370, online

- Bearak, Max (June 20, 2016). "This tiny stretch of countryside is all that separates Baltic states from Russian envelopment". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- Sytas, Andrius (June 18, 2017). "NATO war game defends Baltic weak spot for first time". Reuters. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- Kancelaria Sejmu RP. "Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych". sejm.gov.pl.

- Stephen Kabera Karanja (January 2008). Transparency and Proportionality in the Schengen Information System and Border Control Co-Operation. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 39. ISBN 978-90-04-16223-5.

- "Europe's border-free zone expands". BBC News. 27 December 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "Nowe polsko-litewskie drogi po wejściu do Schengen". DELFI. 28 July 2012.

- "Wspólne patrole na polsko-litewskiej granicy :: społeczeństwo". Kresy.pl.

- "Przemyt papierosów przy polsko – litewskiej granicy [ZDJĘCIA]". bialystok.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lithuania-Poland border. |

- "Lithuania–Poland cross-border cooperation programme, a EU programme". Archived from the original on 2008-07-18.

- "Suwalki Gap". GlobalSecurity.org.

- "Securing The Suwałki Corridor: Strategy, Statecraft, Deterrence, and Defense".

- "This tiny stretch of countryside is all that separates Baltic states from Russian envelopment".