MILAN

MILAN (French: Missile d'infanterie léger antichar; "Light anti-tank infantry missile", milan is French for kite) is a Western European anti-tank guided missile. Design of the MILAN started in 1962, it was ready for trials in 1971, and was accepted for service in 1972. It is a wire-guided SACLOS (semi-automatic command to line-of-sight) missile, which means the sight of the launch unit has to be aimed at the target to guide the missile. The MILAN can be equipped with a MIRA or MILIS thermal sight to give it night-firing ability.

| MILAN | |

|---|---|

MILAN missile launcher with tripod. | |

| Type | Anti-tank missile |

| Place of origin | France / West Germany |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1972–present |

| Used by | See operators |

| Wars | South African Border War Chadian-Libyan conflict Toyota War Western Sahara War[1] Lebanese Civil War Iran–Iraq War Falklands War Gulf War 2003 invasion of Iraq Iraq War Opération Licorne[2] Libyan Civil War Northern Mali Conflict[3] Operation Sangaris[4] Syrian Civil War Iraqi Civil War 2017 Iraqi–Kurdish conflict 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1970s |

| Manufacturer | MBDA Also produced under license by: Bharat Dynamics (India) BAe Dynamics (United Kingdom) |

| Unit cost | £7,500 (1984)[5] |

| Produced | 1972 |

| No. built | 350,000 missiles, 10,000 launchers |

| Variants | See variants |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 16.4 kg[6] |

| Length | 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) |

| Diameter | 0.115 m (4.5 in) |

| Warhead | Single or tandem HEAT |

Detonation mechanism | contact |

| Engine | solid-fuel rocket |

| Wingspan | 0.26 m (10 in) |

Operational range | 200–2,000 m (660–6,560 ft); 3,000 m (MILAN ER) |

| Maximum speed | 200 m/s (660 ft/s) |

Guidance system | SACLOS wire |

Steering system | Jet deflector |

Launch platform | Individual, vehicle |

Background

MILAN is a product of Euromissile, a Franco-West German missile development program dating back to the 1960s. The system entered service in 1972 as a second generation anti-tank weapon and soon became a standard anti-tank weapon throughout NATO, in use by most of the alliance's individual armies.[7]

Consisting of two main components, the launcher and the missile, the MILAN system utilizes a semi-automatic command to line of sight (SACLOS) command guidance system. It tracks the missile either by a tail-mounted infrared lamp or an electronic-flash lamp, depending on the model. Because it is guided by wire by an operator, the missile cannot be affected by radio jamming or flares. However, drawbacks include its short range, the exposure of the operator, problems with overland powerlines, and a vulnerability to infrared jammers such as Shtora that can prevent the automatic tracking of the missile's IR tail light.

The MILAN 2 variant, which entered service with the French, German and British armies in 1984, utilizes an improved 115 mm HEAT warhead. The MILAN 3 entered service with the French army in 1995 and features a new-generation localizer that makes the system more difficult to jam electronically.[8]

Variants

_1986.jpg.webp)

- MILAN 1: Single, main shaped charge warhead (1972), calibre 103 mm

- MILAN 2: Single, main shaped charge warhead, with standoff probe to increase penetration (1984) – see photo to right, calibre 115 mm

- MILAN 2T: Single main shaped charge, with smaller shape charge warhead at end of standoff probe to defeat reactive armour (1993)

- MILAN 3: Tandem, shaped charge warheads (1996) and electronic beacon

- MILAN ER: Extended range (3,000 m) and improved penetration

The later MILAN models have tandem HEAT warheads. This was done to keep pace with developments in Soviet armour technology – Soviet tanks began to appear with explosive reactive armour, which could defeat earlier ATGMs. The smaller precursor HEAT warhead penetrates and detonates the ERA tiles, paving the way for the main HEAT warhead to penetrate the armour behind.

Combat use

Afghanistan

MILAN missile systems were among the numerous weapons sent to the Mujahideen in Afghanistan in the 1980s by the United States to combat Soviet troops.[9] The MILAN had a devastating effect on Soviet armor, having a similar effect on tanks and armored personnel carriers as Stinger missiles had had on Soviet helicopters.[10] In 2010, French troops killed four Afghan civilians in Kapisa Province using a MILAN system during a firefight.[11]

Chadian–Libyan conflict

MILAN missiles provided by the French government saw common usage during the war between Chad and Libya where they were used by Chadian forces. Often mounted on Toyota pickup trucks, the missiles successfully engaged Libyan armor in the Aouzou Strip including T-55 tanks on many occasions.[12]

Syria

In 1977, Syria ordered about 200 launchers and 4,000 missiles, which were delivered in 1978-1979. They were used by the Syrians during the Lebanese Civil War.[13] The missiles were in service during the Syrian Civil War, being for instance fielded by the Republican Guard.[14] The Syrian rebels captured some in depots, as did ISIL. The Kurdish YPG also fired Milans supplied by the international coalition.[13]

Gulf War

MILAN was used by both coalition and Iraqi forces during the Persian Gulf War, with one MILAN launcher operated by French forces having destroyed seven T-55 tanks.[15]

Iraq

Iraq operated MILAN missiles supplied by the French government during the 1980s. Those missiles were used by Iraqi forces during both Gulf Wars.

In 2015, Germany supplied the Peshmerga with 30 MILAN launchers and over 500 missiles.[16][17] Those missiles were mostly used against ISIS forces, but on 20 October during the 2017 Iraqi–Kurdish conflict, Kurdish forces destroyed an Iraqi M1 Abrams tank and several Humvees using the MILANs.[18]

Falklands War

In 1982 the military junta ruling Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, a UK overseas territory, leading to the Falklands War. The British forces tasked to retake the islands used MILAN as part of their land forces missile systems, along with the HEAT L1A1 and Carl Gustaf 8.4cm recoilless rifle. Armoured warfare was largely absent from that conflict, but such systems proved useful in their secondary 'bunker buster' role to attack strongpoints in the largely open territory which characterised the campaign. The MILAN saw invaluable use for example in the battles for Goose Green, Mount Longdon, Two Sisters and Wireless Ridge.[19]

Operators

Current operators

Afghanistan – Afghan National Army and Talibans[20]

Afghanistan – Afghan National Army and Talibans[20] Armenia – Armed Forces of Armenia[21]

Armenia – Armed Forces of Armenia[21].svg.png.webp) Belgium – Belgian Army: Infantry weapon; replaced by Spike-LR in 2014[22]

Belgium – Belgian Army: Infantry weapon; replaced by Spike-LR in 2014[22] Botswana[23] - Botswana Defence Force[24]

Botswana[23] - Botswana Defence Force[24] Brazil – Brazilian Army[23]

Brazil – Brazilian Army[23] Burundi (reported)[23]

Burundi (reported)[23] Cambodia - 25 systems[23]

Cambodia - 25 systems[23] Chad – Chadian Ground Forces: used on light vehicles[25][26]

Chad – Chadian Ground Forces: used on light vehicles[25][26] Croatia (reported)[23]

Croatia (reported)[23] Cyprus – Cypriot National Guard[23] 45 launchers

Cyprus – Cypriot National Guard[23] 45 launchers Estonia – Estonian Defence Forces[23] Will be replaced by Spike-LR II in 2021.

Estonia – Estonian Defence Forces[23] Will be replaced by Spike-LR II in 2021. Egypt[23] – Egyptian Army: Mounted on light vehicles. 220 units are used.

Egypt[23] – Egyptian Army: Mounted on light vehicles. 220 units are used. France – French Army: Infantry and vehicle-mounted weapon. Will be replaced by Missile Moyenne Portée (MMP) from 2017.[27]

France – French Army: Infantry and vehicle-mounted weapon. Will be replaced by Missile Moyenne Portée (MMP) from 2017.[27] Gabon - 4 systems[23]

Gabon - 4 systems[23] Germany – Bundeswehr: Mounted primarily on Marder and TPz Fuchs fighting vehicles; to be replaced by EUROSPIKE.

Germany – Bundeswehr: Mounted primarily on Marder and TPz Fuchs fighting vehicles; to be replaced by EUROSPIKE. Greece – Hellenic Army[23] 400 Launchers

Greece – Hellenic Army[23] 400 Launchers India – Indian Army: Infantry and vehicle-mounted weapon. Around 30,000 built under license by Bharat Dynamics. The Indian Army has also spent close to US$120 million on 4,100 new MILAN-2T ATGMs.[28]

India – Indian Army: Infantry and vehicle-mounted weapon. Around 30,000 built under license by Bharat Dynamics. The Indian Army has also spent close to US$120 million on 4,100 new MILAN-2T ATGMs.[28] Indonesia[23]

Indonesia[23] Iraq – Iraqi Army: One reportedly hit a British Challenger 2 MBT during the early stages of Operation Telic along with multiple rocket-propelled grenades. The tank survived the attack.

Iraq – Iraqi Army: One reportedly hit a British Challenger 2 MBT during the early stages of Operation Telic along with multiple rocket-propelled grenades. The tank survived the attack.

Kurdistan – Peshmerga: 30 launchers and 500 missiles, delivery in two portions was announced on August 31, 2014 by German Bundeswehr. These are 1980s Milan 2 replaced by later models but still in storage.[29][30] Used by the Kurds to stop ISIL vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs).[31]

Kurdistan – Peshmerga: 30 launchers and 500 missiles, delivery in two portions was announced on August 31, 2014 by German Bundeswehr. These are 1980s Milan 2 replaced by later models but still in storage.[29][30] Used by the Kurds to stop ISIL vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs).[31]

Italy – Italian Army: Infantry weapon. Built under license by Oto Melara; Total of 714 launchers with 17,163 missile delivered in 1990. 807 MILAN 2T ordered in 2004 and delivered in 2005 (SIPRI).[32]

Italy – Italian Army: Infantry weapon. Built under license by Oto Melara; Total of 714 launchers with 17,163 missile delivered in 1990. 807 MILAN 2T ordered in 2004 and delivered in 2005 (SIPRI).[32] Jordan - used on YPR 765 vehicles[23]

Jordan - used on YPR 765 vehicles[23] Kenya[23] – Kenyan Army: Infantry weapon.

Kenya[23] – Kenyan Army: Infantry weapon. Lebanon – Lebanese Army[23]

Lebanon – Lebanese Army[23] Libya – Libyan National Army : 1,000 MILAN-3 exported between 2008 and 2011,[33] 400 systems in 2011.

Libya – Libyan National Army : 1,000 MILAN-3 exported between 2008 and 2011,[33] 400 systems in 2011. North Macedonia – Army of the Republic of Macedonia[23]

North Macedonia – Army of the Republic of Macedonia[23] Mauritania – Mauritanian Army[23]

Mauritania – Mauritanian Army[23] Mexico[23] – Mexican Army (Ejército Mexicano): Mounted primarily on Panhard VBL scout cars; at least 16 launchers and several hundred missiles are available.

Mexico[23] – Mexican Army (Ejército Mexicano): Mounted primarily on Panhard VBL scout cars; at least 16 launchers and several hundred missiles are available. Morocco – Royal Moroccan Army

Morocco – Royal Moroccan Army Oman[23]

Oman[23] Portugal[23] – Portuguese Army; Portuguese Marines

Portugal[23] – Portuguese Army; Portuguese Marines PKK : As per the Der Spiegel, PKK acquired the MILAN anti tank missiles[34]

PKK : As per the Der Spiegel, PKK acquired the MILAN anti tank missiles[34] South Africa – South African Army: 375 missiles.[35][36][37][38][39]

South Africa – South African Army: 375 missiles.[35][36][37][38][39] Qatar[23]

Qatar[23] Senegal - 4 systems[23]

Senegal - 4 systems[23] Spain[23] – Spanish Army: Upgraded to MILAN 2/2T.

Spain[23] – Spanish Army: Upgraded to MILAN 2/2T. Singapore: 30 systems[23]

Singapore: 30 systems[23] Syria[23] – Syrian Army

Syria[23] – Syrian Army

.svg.png.webp) Free Syrian Army: Some captured.[40]

Free Syrian Army: Some captured.[40] YPG[13]

YPG[13] Islamic State[13]

Islamic State[13]

Tunisia – Tunisian Armed Forces: 120 missiles.[35]

Tunisia – Tunisian Armed Forces: 120 missiles.[35] Turkey – Turkish Army[23]

Turkey – Turkish Army[23] United Arab Emirates[23]

United Arab Emirates[23] Uruguay – Uruguayan Army[23]

Uruguay – Uruguayan Army[23] Yemen – Yemeni security forces

Yemen – Yemeni security forces

Former operators

.svg.png.webp) Australia – Australian Army: Was used by infantry and mounted on vehicles. The Australian Army withdrew the MILAN from service in the early 1990s. The ADF now fields the FGM-148 Javelin system.

Australia – Australian Army: Was used by infantry and mounted on vehicles. The Australian Army withdrew the MILAN from service in the early 1990s. The ADF now fields the FGM-148 Javelin system. Ireland – Irish Army: Infantry weapon; replaced by the FGM-148 Javelin.

Ireland – Irish Army: Infantry weapon; replaced by the FGM-148 Javelin. Singapore – Singapore Army: Replaced by the Israeli Spike.

Singapore – Singapore Army: Replaced by the Israeli Spike. Somalia - imported in 1978-1979[41]

Somalia - imported in 1978-1979[41] UNITA: 150 missiles.[35]

UNITA: 150 missiles.[35] United Kingdom – British Army; Royal Marines – While primarily an infantry weapon, it was also used in the FV120 Spartan MCT turret. Over 50,000 missiles were purchased for use in the British Armed Forces. The MILAN was deployed against Argentine bunkers in the Falklands conflict[42] and later against T-55s during the Persian Gulf War.[43] It was replaced by the FGM-148 Javelin in mid-2005. Previously made under licence by British Aerospace Dynamics.[44]

United Kingdom – British Army; Royal Marines – While primarily an infantry weapon, it was also used in the FV120 Spartan MCT turret. Over 50,000 missiles were purchased for use in the British Armed Forces. The MILAN was deployed against Argentine bunkers in the Falklands conflict[42] and later against T-55s during the Persian Gulf War.[43] It was replaced by the FGM-148 Javelin in mid-2005. Previously made under licence by British Aerospace Dynamics.[44]

Gallery

A Bundeswehr Marder infantry fighting vehicle fires a MILAN.

A Bundeswehr Marder infantry fighting vehicle fires a MILAN. MILAN, 2007

MILAN, 2007 German Army MILAN equipped with an AGDUS combat simulator

German Army MILAN equipped with an AGDUS combat simulator Vehicle mounted launcher and missiles in Egyptian service during Operation Desert Shield, 1992.

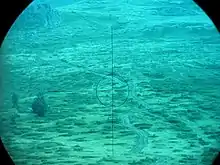

Vehicle mounted launcher and missiles in Egyptian service during Operation Desert Shield, 1992. Missile impact on a training target, 2001.

Missile impact on a training target, 2001.

References

- Notes

- Delcour, Roland (19 January 1982). "À Ras-el-Khanfra, les efforts du Polisario pour rompre le mur de sécurité entourant le " Sahara utile " ont échoué". Le Monde (in French).

- Hofnung, Thomas (3 July 2006). "Soldats tués à Bouaké : la France a laissé faire". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Capdeville, Thibault (Spring 2014). "Infantry units fires during OP Serval" (PDF). Fantassins. No. 32. pp. 55–58. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- "RCA: violent accrochage entre Sangaris et des rebelles à Boguila". Radio France Internationale (in French). Archived from the original on 2018-09-04. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- "Written Answers Defence: Weapons and Equipment (Costs)", House of Commons Debates, UK Parliament, vol 63, column 453W, 10 July 1984, archived from the original on 17 June 2016, retrieved 21 May 2016

- "Milan". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ARG. "MILAN Anti-Tank Guided Missile". Military-Today.com. Archived from the original on 2018-02-27. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- Pike, John (2018-03-09). "Milan". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-10. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- Bobi Pirseyedi (2000). The Small Arms Problem in Central Asia: Features and Implications. United Nations Publications UNIDIR. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-92-9045-134-1.

- Jack Devine; Vernon Loeb (3 June 2014). Good Hunting: An American Spymaster's Story. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-374-13032-9.

- "French army claims responsibility for four civilian deaths in Afghanistan". France 24. 2010-04-29. Archived from the original on 2018-03-10. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "TOPICS OF THE TIMES; Toyotas and Tanks". The New York Times. 1987-08-16. Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "Comment l'Etat islamique a récupéré des lance-missiles Milan français" [How ISIS got French Milan missiles]. France Soir (in French). 7 December 2018. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "La 104ème brigade de la Garde républicaine syrienne, troupe d'élite et étendard du régime de Damas". France-Soir (in French). 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Jayhawk! the VII Corps in the Persian Gulf War. Stephen Alan Bourque, United States. Dept. of the Army.

- "Germany sends more MILAN rockets to thwart ISIS suicide bombers". Archived from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- "Kampf gegen IS: Mehr deutsche Waffen für Kurden". Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- "Lostarmour ID - 16603, M1A1M Abrams, Erbil". lostarmour.info. Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- Falklands War Operations Manual. Haynes, Chris McNab, 2018, ISBN 978 1 78521 185 0

- "Afghanistan : Des missiles Milan aux mains des insurgés". Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- "Armenia purchases France-Germany co-produced anti-tank missile systems". Apa.az. 1 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Belgium selects Spike missile to replace Milan Archived 2017-06-29 at the Wayback Machine – Armyrecognition.com, January 3, 2013

- "Future Artillery Systems: 2016 Market Report" (PDF). Tidworth: Defence IQ. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- Martin, Guy. "Botswana - defenceWeb". www.defenceweb.co.za. Archived from the original on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- "Libye: le retour de la "cavalerie Toyota"". 30 March 2011. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- La-Croix.com (30 January 2012). "Au Tchad, l'argent du pétrole finance surtout les armes". La Croix. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- France Orders Anti-Tank Missile from MBDA – Defensenews.com, 5 December 2013

- "Not Found". www.india-defence.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-17. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- "Unterstützung der Regierung der Autonomen Region Irakisch-Kurdistan bei der Versorgung der Flüchtlinge und beim Kampf gegen den Islamischen Staat im Nordirak (PDF)" (PDF). German Bundeswehr (in German). 31 August 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- "Irak: Deutschland schickt Kurden Panzerabwehrraketen". Spiegel Online (in German). 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- French, American Weapons Take Toll on ISIS in Ground Combat Archived 2017-07-12 at the Wayback Machine - Military.com, 16 November 2015

- "Nasce " Revestito " a Messina. Una Rivista on line per tutti. Per tutti coloro che non tollerano più demagogia, privilegio, mistificazioni di poteri grossi o piccoli, che hanno messo alle strette l´umanità, la libertà, e soprattutto la dignità. Revestito ha significato ambivalente: non occorre che sia messo a nudo il re ,per evento eccezionale, affinchè la natura delle cose in qualche misura si disveli. La trasparenza dovrebbe essere alla base di ogni consorzio civile e di ogni Stato di diritto che tale pretenda definirsi". 23 April 2014. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014.

- Small Arms Survey (2015). "Trade Update: After the 'Arab Spring'" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2015: weapons and the world (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 102. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-28. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- "Kampf gegen IS-Miliz: Ausrüstung der Bundeswehr möglicherweise in die Hände der PKK gelangt". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 2015-02-15. Retrieved 2015-02-14.

- "Trade Registers". Armstrade.sipri.org. Archived from the original on 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- B A Lowe (4 January 2009). "SADF Arms Purchases". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

75 MILAN launchers ordered in 1973 and delivered in 1974

-

Moukambi, Victor (December 2008). RELATIONS BETWEEN SOUTH AFRICA AND FRANCE WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MILITARY MATTERS, 1960-1990 (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation thesis). Stellenbosch: Military Science, Stellenbosch University. p. 116. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

In December 1973, it was reported that [Pretoria] signed a contract.. for the supply of 50 Matra 550 air-to-air missiles ..[and] a contract over the supply of 1500 Milan missiles. Source: French Defence Ministry; Historical Archives, Paris, Box No. 14 S 295, Monthly report of the French Military Attaché in South Africa, Imports from France, November 1973. Report of the French Military Attaché in South Africa, November 1973.

- Leon Engelbrecht (8 October 2008). "SANDF Army, SOF "operationalising" MILAN". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

The launchers were received in 1974, but were placed in storage in 1996. SA employed the MILAN in combat in southern Angola in the 1980s. Under Project Kingfisher, 30 launchers were upgraded to Milan ADT-ER status and 300 missiles were acquired for R167.4 million.

- Leon Engelbrecht (24 May 2011). "SA Army stocks up on Milan 3". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

The SANDF has ordered an undisclosed further number of Milan missiles..The R57 990 630.80 purchase order was awarded to Euromissile [sic] last week. It takes the known value of Project Kingfisher – according to the Armscor Bulletin System (ABS) – to R271 076 483.37...The Kingfisher contract was placed on December 20, 2006, and initially escaped media notice. In March 2009 the military ordered a further 13 Milan ADT firing posts and four simulators under a contract worth €10.7 million (about R129.3 million at then exchange rates, but R81.5 million on the ABS.

- "Syrian rebels captured ammunition depot with Milan / Konkurs anti-tank missiles and rockets". Armyrecognition.com. 5 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10.

- Small Arms Survey (2012). "Surveying the Battlefield: Illicit Arms In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia". Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets. Cambridge University Press. pp. 339–340. ISBN 978-0-521-19714-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- "British Land Weapons and Vehicles". www.britains-smallwars.com. Archived from the original on 2005-12-02.

- Zaloga (2004), p. 36.

- "British Army - The Infantry - Milan 2 - Armed Forces - a5a14". www.armedforces.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-03-19. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MILAN. |

- Technical data sheet on the website of MBDA

- GlobalSecurity.org

- Information about The British Army's Milan 2

- Video link