Malachy Salter

Malachy Salter (February 28, 1715 – January 13, 1781), a Nova Scotian merchant and office-holder, who was convicted of sedition for betraying the Loyalists during the American Revolution.[1] [2]

Malachy Salter | |

|---|---|

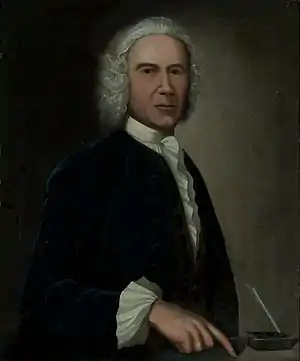

Malachy Salter by John Smybert, Province House (Nova Scotia), from the collections of the Nova Scotia Legislative Library | |

| MLA for Yarmouth township | |

| In office 1766–1772 | |

| MLA for Halifax township | |

| In office 1759–1765 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 28, 1715 Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died | January 13, 1781 (aged 65) Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Spouse(s) | Susanna Mulberry |

| Occupation | Businessman, politician |

Business career

He operated a successful Boston distillery, along with his Holmes uncles, and was the senior partner in a firm involved in the fisheries and the West Indies trade. He relocated to Halifax, Nova Scotia during Father Le Loutre's War and engaged in shipping ventures which brought him both North American and European goods, and extended credit, prosecuted debts, and settled estates. He purchased Halifax properties, which included the over-extended poor, likely the source of the comment that he was a "Litigious troublesome Man… who has treated us in a Barbarous cruel manner."

In 1754 Salter expanded his operations into the field of government contracts. He was subsequently called upon to provide certain mercantile evaluations for the government.

Salter was an early member of the grand jury in Halifax and served as a captain of militia (1761–1762) and an Overseer of the Poor (1765–1766). In 1757, he became a leader in the committee of Halifax freeholders which used legal effort to force Governor Charles Lawrence to convene a representative assembly in October 1758, Salter was amongst its 20 members.

For 15 years Salter sat in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly, representing Halifax Township from 1759 to 1765 and Yarmouth Township from 1766 to 1772.

During the Seven Years’ War Salter was owner, with other Halifax entrepreneurs, of the privateer ship Lawrence. With his development of a sugar-house at Halifax in the mid-1760s. This and his American trade connections enabled him to capitalize upon the embargos placed on British goods by the Thirteen Colonies in the late 1760s. Despite his various interests, and further government contracts during the administration of Michael Francklin his fortunes continued to follow the decline of the Nova Scotia economy. In 1768 shipping and other losses were too much and after two years settling his debts in Nova Scotia and New England, he operated his sugar-house himself. In 1773 he built a vessel at Liverpool, Nova Scotia to return to the sea, as a trader, where he had begun - as a youth.

American Revolution

Salter was tried and convicted for uttering seditions words in February 1777. In November 1777, he was also charged with the serious misdemeanour of treasonable correspondence. Because of poor health, his trial was postponed and hung over him for the last three years of his life.[3]

Later the same year his brig Rising Sun was captured by Salem privateers as prize. When prisoner in New England, he obtained a pass from the Massachusetts government to settle his family there. On his return to Halifax later that year, he saw continued court proceedings against him.

Salter has been ranked by historians among the most important entrepreneurs of early Halifax, yet he failed to establish himself securely within its profitable network.

The large house he constructed at the corner of Hollis and Salter streets, about 1760 was eventually purchased by William Lawson and, later demolished to become part of the site of Maritime Place, in downtown Halifax.

Family

He was born at Boston, second son of Malachy Salter and Sarah Holmes. He married Susanna Mulberry, on 26 July 1744 in Boston, and they had at least 11 children. He died at Halifax, Nova Scotia and is buried in the Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia) (His son Malachi Salter (d.1752) has the oldest grave marker in the burying ground).

Legacy

- namesake of Salter Street, Halifax

- namesake Salter Street Films, a media production house

References

- Barry Cahill, "The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution", Acadiensis, Vol. 26, 1 (Autumn 1996), p. 53

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Barry Cahill, "The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution", Acadiensis, Vol. 26, 1 (Autumn 1996), p. 53