Max Letteris

Max (Meïr Halevi or Myer Levi) Letteris (September 13, 1800, Zolkiev – May 19, 1871, Vienna) was an Austrian Jewish scholar and the foremost poet of the Galician Haskala.

Life

Letteris was a member of a family of printers that originally came from Amsterdam. At the age of twelve he sent a Hebrew poem to Nachman Krochmal, who was then living at Zolkiev. Subsequently he made the acquaintance of Krochmal, who encouraged him in his study of German, French, and Latin literature. In 1826, he entered the University of Lemberg, where for four years he studied philosophy and Oriental languages. In 1831, he went to Berlin as Hebrew corrector in a printing establishment, and later in a similar capacity to Presburg, where he edited a large number of valuable manuscripts, and to Prague, where he received the degree of Ph. D. (1844). In 1848 he settled finally in Vienna.

Letteris' chief poetical work in German, Sagen aus dem Orient (Karlsruhe 1847), consisting of poetic renderings of Talmudic and other legends, secured for him, though for a short time, the post of librarian in the Oriental department of the Vienna Imperial Library. His reputation as the foremost poet of the Galician school is based on his volume of poems Tofes Kinnor we-'Ugab (Vienna, 1860), and especially on his Hebrew version of "Faust," entitled "Ben Abuya" (ib. 1865). He exerted a considerable influence on Hebrew poetry. One of his best poems is his Zionistic song Yonah Ḥomiyyah, became very popular. His numerous translations are of value, but his original poems are as a rule prolix. His Hebrew prose is correct, though heavy.

In his Hebrew version of Faust, Faust is replaced by the Jewish heretic Elisha ben Abuyah. For the infidelity of his "translation" to Goethe's original, Letteris was the object of a blistering attack by the young Peretz Smolenskin.[1]

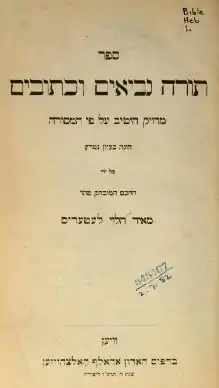

The Letteris Bible

In 1852, during a period in which he faced financial difficulties, he agreed to edit an edition of the masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible.[2] In 1866 he produced a revised edition for a Christian missionary organization, the British and Foreign Bible Society. This revision was checked against old manuscripts and early printed editions.[3] Its typeface is highly legible and it is printed in a clear single-column format per page. It is probably the most widely reproduced text of the Hebrew Bible in history, with many dozens of authorised reprints and many more pirated and unacknowledged ones.[4]

This revised edition became very popular, and was widely reprinted in both Jewish circles (often accompanied by a translation on facing pages) and in Christian circles (with the addition of the New Testament).

Other works

Besides the works already mentioned the following deserve special notice:

- Dibre Shir (Zolkiev, 1822) and "Ayyelet ha-Shachar" (ib. 1824), including translations from Schiller and Homer, and poems by Letteris' father

- Ha-[?]efirah (Zolkiev and Leipsic, 1823), a selection of poems and essays

- Palge Mayim (Lemberg, 1827), poems

- Gedichte (Vienna, 1829), German translations from the Hebrew

- Geza' Yishai (Vienna, 1835), Hebrew translation of Racine's "Athalie"

- Shelom Ester (Prague, 1843), Hebrew translation of Racine's "Esther"

- Spinoza's Lehre und Leben (Vienna, 1847)

- Neginot Yisrael, Hebrew rendering of Frankel's "Nach der Zerstreuung" (ib. 1856)

- Bilder aus dem Biblischen Morgenlande (Leipsic, 1870).

He was the editor of Wiener Vierteljahrsschrift, with a Hebrew supplement, Abne Nezer (ib. 1853), and of Wiener Monatsblätter für Kunst und Litteratur(ib. 1853).

See also

References

- Being for myself alone: origins of Jewish autobiography, by Marcus Moseley, p. 77-8.

- The entire text of the first Letteris edition can be viewed here. This first edition by Letteris was printed in two columns per page; see Mordechai Breuer, "The Aleppo Codex as Described by Israel Yeivin", Leshonenu: A Journal for the Study of the Hebrew Language and Cognate Subjects (1971), p. 88 and n. 3 (Hebrew); accessible here. According to Breuer, this edition was the only widely distributed edition of the Hebrew Bible to present the Psalms according to the Heidenheim-Baer edition.

- This second edition, according to Breuer (ibid.), shows the Heidenheim-Baer text only for Psalms 1-55; that first ream of the book was apparently prepared by an editor from the Heidenheim school.

- Harry M. Orlinsky, Prolegomenon to the 1966 reprint of Christian Ginsburg, "Introduction to the Massoretico-Critical Edition of the Hebrew Bible".

- Julius Fürst, Orient, Lit. 1849, pp. 633 et seq.;

- idem, Bibl. Jud. ii. 234;

- Zikkaron ha-Sefer, Vienna, 1869 (autobiographical notes by Letteris);

- Allg. Zeit. des Jud. 1871, p. 692;

- G. Bader, in Aḥiasaf, 1903;

- Nahum Slouschz, La Renaissance de la Littérature Hébraïque, pp. 51–53, Paris, 1902.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meïr Halevi Letteris. |

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Missing or empty |title= (help)