Megalosauridae

Megalosauridae is a monophyletic family of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs within the group Megalosauroidea, closely related to the family Spinosauridae. Some members of this family include Megalosaurus, Torvosaurus, Eustreptospondylus, and Afrovenator. Appearing in the Middle Jurassic, megalosaurids were among the first major radiation of large theropod dinosaurs, although they became extinct by the end of the Jurassic period.[1] They were a relatively primitive group of basal tetanurans containing two main subfamilies, Megalosaurinae and Afrovenatorinae, along with the basal genus Eustreptospondylus, an unresolved taxon which differs from both subfamilies.[2]

| Megalosaurids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal mount of Torvosaurus tanneri, Museum of Ancient Life | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Megalosauroidea |

| Family: | †Megalosauridae Huxley, 1869 |

| Type species | |

| †Megalosaurus bucklandii Mantell, 1827 | |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

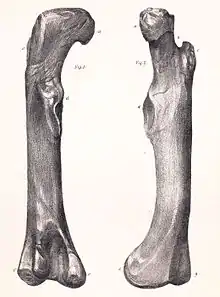

The defining megalosaurid is Megalosaurus bucklandii, first named and described in 1824 by William Buckland after multiple finds in Stonesfield, Oxfordshire, UK. Megalosaurus was the first formally described dinosaur and was the basis for the establishment of the clade Dinosauria. It is also one of the largest known Middle Jurassic carnivorous dinosaurs, with the best-preserved femur at 805 mm and a proposed body mass of around 943 kg.[3] Megalosauridae is recognized as a mainly European group of dinosaurs, based on fossils found in France and the UK. However, recent discoveries in Niger have led some to consider the range of the family. Megalosaurids appeared right before the split of the supercontinent Pangaea into Gondwana and Laurasia.[4] These large theropods therefore may have dominated both halves of the world during the Jurassic.[5]

The family Megalosauridae was first defined by Thomas Huxley in 1869, yet it has been contested throughout history due to its role as a "waste-basket" for many partially described dinosaurs or unidentified remains.[6] In the early years of paleontology, most large theropods were grouped together and up to 48 species were included in the clade Megalosauria, the basal clade of Megalosauridae. Over time, most of these taxa were placed in other clades and the parameters of Megalosauridae were narrowed significantly. However, some controversy remains over whether Megalosauridae should be considered its own distinct group, and dinosaurs in this family remain some of the most problematic taxa in all Dinosauria.[5][6] Some paleontologists, such as Paul Sereno in 2005, have disregarded the group due to its shaky foundation and lack of clarified phylogeny. However, recent research by Carrano, Benson, and Sampson has systematically analyzed all basal tetanurans and determined that Megalosauridae should exist as its own family.

Description

Body size

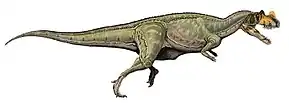

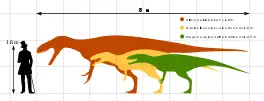

Like other tetanurans, megalosaurids are carnivorous theropods characterized by large size and bipedalism. Specifically, megalosaurids exhibit especially giant size, with some members of the family weighing more than one tonne. Over time, there is evidence of size increase within the family. Basal megalosaurids from the Early Jurassic had smaller body size than those appearing in the late Middle Jurassic. Due to this size increase over time, Megalosauridae appear to follow a size increase pattern similar to that of other giant sized theropods like Spinosauridae.[2] This pattern follows Cope's Rule, the postulation by paleontologist Edward Cope about evolutionary increase in body size.[5][7]

Anatomical characteristics

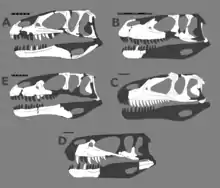

One unambiguous synapomorphy of Megalosauridae is a lower and longer skull with a length to height ratio of 3:1. In addition, the typical skull roof tends to be much less ornamented than that of other tetanurans, and crests or horns are either very small or absent entirely. Megalosaurids also have femoral heads with an orientation 45 degrees between anteromedial and fully medial. Megalosauridae are also defined by the following unique unambiguous synapomorphies:[1][2]

- A humeral deltopectoral crest that terminates about halfway along the humeral shaft

- The absence of a fibular anterolateral tubercle.

- Nares which extend as far as the premaxillary teeth, yet the portion of the premaxilla anterior to the nares being longer than the portion under them; angled snout tip (angle between the anterior and alveolar margins <70 degrees).

- Medial foramina on the quadrate adjacent to the mandibular condyles.

- Pleurocoelous fossae on the sacral vertebrae.

- The oblique ligament groove on the posterior surface of the femoral head is shallow.

Megalosaurinae (all megalosaurids more closely related to Megalosaurus than Afrovenator) are characterized by a moderate (0.5-2.0) height/length ratio of the premaxilla below the level of the nares, compared to other megalosaurids which have a lower ratio and thus less tall snout tip.

Afrovenatorinae (all megalosaurids more closely related to Afrovenator than Megalosaurus) are characterized by a squared anterior margin of the antorbital fossa and the puboischiadic plate being broadly open along the midline.

Dental morphology

Dental findings are frequently used to differentiate between various theropods and to further inform cladistic phylogeny. Tooth morphology and dental evolutionary markers are prone to homoplasy and disappear or reappear throughout history. However, megalosaurids have several specific denture conditions that differentiate them from other basal theropods. One dental condition present in Megalosauridae is multiple enamel wrinkles near the carinae, the sharp edge or serration row of the tooth. Ornamented teeth and a well-marked enamel surface also characterize basal megalosaurids. The ornamentation and well-marked surface appears in early megalosaurids but disappears in derived megalosaurids, suggesting that the condition was lost over time as megalosaurids grew in size.[8]

Classification

Historical classification

From the family's inception, many specimens found in the field have been wrongly classified as megalosaurids. For example, most large carnivores found for about a century after the naming of Megalosaurus bucklandii were placed in Megalosauridae. Megalosaurus was the first paleontological finding of its kind when William Buckland discovered a giant femur and named it in 1824, predating even the term Dinosauria.[1] When initially defined, the species M. bucklandii was anatomically based on various dissociated bones found in quarries around the village of Stonesfield, UK. Some of these early findings included a right dentary with a well-preserved tooth, ribs, pelvic bones, and sacral vertebrae.[9] As early paleontologists and researchers found more dinosaur bones in the surrounding area, they attributed them all to M. bucklandii since it was the only named and described dinosaur at this point in history. Therefore, the species was initially described and classified by a mass of possibly unrelated characteristics.[3]

Modern paleontology first began to approach the problematic cladistic separation of Megalosauridae during the early 20th century. Fredrich von Huene separated carnivorous theropods, which had all been grouped into the broad category of megalosaurids, into two distinct families of larger, more giant sized and smaller, more lightly built theropods. These two groups were named Coelurosauria and Pachypodosauria respectively. Later on, Huene distinguished between carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs in Pachypodosauria, placing the meat-eaters in a new group Carnosauria.[2]

As more information was uncovered about basal theropods and phylogenetic characteristics, modern paleontologists began to question the proper naming for this group. In 2005 paleontologist Paul Sereno rejected the use of the clade Megalosauridae due to its ambiguous early history in favor of the name Torvosauridae.[10] Today, it is accepted that megalosaurids existed at least as a group of basal tetanurans, due to the fact that they have more derived taxa than ceratosaurs[2] and that the name Megalosauridae should represent this group. Megalosauridae also has priority over Torvosauridae under ICZN rules governing family names.[10]

Phylogeny

Megalosauridae was first phylogenetically defined in 1869 by Thomas Huxley, yet was used as a ‘waste-basket’ clade for many years. In 2002, Ronan Allain redefined the clade after he discovered a complete megalosaurid skull in northwestern France of species Poekilopleuron. Using the characters described in this study, Allain defined Megalosauridae as dinosaurs including Poekilopleuron valesdunesis, now known as Dubreuillosaurus, Torvosaurus, Afrovenator, and all descendants of their common ancestor. Allain also defined two taxa within Megalosauridae: Torvosaurinae was defined as all Megalosauridae more closely related to Torvosaurus than to Poekilopleuron and Afrovenator, and Megalosaurinae was defined as all those that are more closely related to Poekilopleuron.[3] Megalosauridae also falls under the basal clade Megalosauroidea, which also contains Spinosauridae. However, many taxa are still quite unstable and cannot be placed in one clade with absolute certainty. For example, Eustreptospondylus and Streptospondylus, while they are both defined as Megalosauridae, are often excluded to make more stable cladograms since they are not defined to a certain subgroup.[1][2] The cladogram presented here follows Benson (2010) and Benson et al. (2010).[11][12]

| Megalosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Then, in 2012, Carrano, Benson, and Sampson did a much larger analysis of tetanurans and defined Megalosauria more broadly as the clade containing Megalosaurus, Spinosaurus, and all its descendants. In other words, Megalosauria is the group that contains the two families Megalosauridae and its close relative Spinosauridae. Within this new cladogram, Megalosauridae was given a new subfamily Afrovenatorinae, which included all megalosaurids more closely related to Afrovenator than Megalosaurus.

Carrano, Benson, and Sampson also included various megalosaurids that had previously been excluded from cladograms in their 2012 study, such as Duriavenator and Wiehenvenator in Megalosaurinae and Magnosaurus, Leshansaurus, and Piveteausaurus in Afrovenatorinae.[2]

| Megalosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scuirumimus albersodoerferi, a small theropod described in 2012 which preserved protofeathers, was initially believed to be a juvenile megalosauroid. This led to the belief that megalosaurids may have had feathers.[13] However, subsequent analyses have placed Sciurimimus as a basal coelurosaur.[14]

In 2019, Rauhut and Pol described Asfaltovenator vialidadi, a basal allosauroid displaying a mosaic of primitive and derived features seen within Tetanurae. Their phylogenetic analysis found traditional Megalosauroidea to represent a basal grade of carnosaurs, paraphyletic with respect to Allosauroidea. This would render Megalosauridae a family of carnosaurs.[15]

| Carnosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

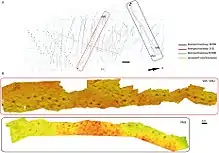

Palaeoecology

Megalosaurids have been suggested to be predators or scavengers inhabiting coastal environments. Middle Jurassic-era tracks believed to have left by megalosaurids have been found at Vale de Meios in Portugal. During the middle Jurassic, this site would have been a tidal flat exposed at low tide on the edge of a lagoon. Unlike most coastal tracks, which are parallel to the coastline and probably left by migrating animals, the Vale de Meios tracks were perpendicular to the coast, with the vast majority oriented towards the lagoon. This indicates that the megalosaurids which would have left these tracks approached the tidal flat once the tide retreated.[16]

This indicates that megalosaurids could have scavenged for the carcasses of marine creatures left by the receding tides. Another possibility is that megalosaurids were piscivorous, approaching the coast to hunt for fish. Spinosaurids, which were close relatives of megalosaurids, had numerous adaptations for piscivory and semiaquatic life, so such a lifestyle is supported by phylogenetic data. Shark teeth, cartilage fragments, and gastroliths have been documented as stomach contents in Poekilopleuron. Both this genus and Dubreillosaurus were discovered in sediments also preserving mangrove roots, providing further evidence for a coastal habitat. Nevertheless, this does not rule out the possibility that megalosaurids also fed on terrestrial prey.[17]

Palaeogeography

Species included in Megalosauridae have been found on every modern continent, split relatively equally between sites on the Gondwana and Laurasia supercontinents. Paleogeography findings show that Megalosauridae was mainly restricted to the Middle to Late Jurassic, suggesting they went extinct at the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary 145 million years ago.[9]

The global radiation of these carnivorous theropods occurred in two steps. First, radiation occurred during Pangaea's breakup during the Early Jurassic, about 200 million years ago. When the Tethys Sea emerged between the supercontinent, megalosauroids radiated to the two halves of Pangaea. The second step of radiation occurred during the Middle and Late Jurassic, 174 to 145 million years ago, in allosauroids and coelurosaurs. Megalosauridae appears to have gone extinct at the end of this time period.[3]

Megalosaurid remains have been found in various areas of the world throughout history. For example, Megalosauridae contains the most primitive theropod embryo ever found, from Early Tithonian Portugal 152 million years ago (mya). In addition, various megalosaurid fossil discoveries have been dated to Bajocian-Callovian England and France 168 to 163 mya, Middle Jurassic Africa about 170 mya, Late Jurassic China 163 to 145 mya, and Tithonian North America about 150 mya.[9] Most recently, megalosaurids have been found in the Tiourarén Formation in Niger, proving again that these basal tetanurans have experienced global radiation.[5]

References

- Benson, R.B.J (2010). "A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (4): 882–935. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00569.x.

- Carrano, Matthew T. (2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927.

- Allain, Ronan (2002). "Discovery of megalosaur (Dinosauria, Theropoda) in the middle Bathonian of Normandy (France) and its implications for the phylogeny of basal tetanurae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 548–563. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0548:DOMDTI]2.0.CO;2.

- Rayfield, E.J. (2011). "Structural performance of tetanuran theropod skulls, with emphasis on the Megalosauridae, Spinosauridae and Carcharodontosauridae". Studies on Fossil Tetrapods. Special Papers in Palaeontology.

- Serrano-Martinez, Alejandro (February 2015). "New theropod remains from the Tiourarén Formation (?Middle Jurassic, Niger) and their bearing on the dental evolution in basal tetanurans". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 126: 107–118. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2014.10.005.

- Benson, R.B.J. (2008). "The taxonomic status of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Middle Jurassic of Oxfordshire, UK". Palaeontology. 51 (2): 419–424. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00751.x.

- Hone, D. (January 1, 2005). "Research Focus: The evolution of large size: how does Cope's Rule work?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution [serial online].

- Erickson, G. (1995). "Split Carinae on Tyrannosaurid teeth and implications of their development". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (2): 268–274. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011229.

- Hendrickx, C. (2015). "An overview of non-avian theropod discoveries and classification". Palarch's Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- Sereno, P.C. (November 7, 2005). "Stem Archosauria". TaxonSearch.

- Benson, R.B.J. (2010). "A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (4): 882–935. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00569.x.

- Benson, R.B.J., Carrano, M.T and Brusatte, S.L. (2010). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...71B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. PMID 19826771.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Supporting Information

- Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (2012). "Exceptionally Preserved Juvenile Megalosauroid Theropod Dinosaur with Filamentous Integument from the Late Jurassic of Germany". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (29): 11746–11751. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10911746R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203238109. PMC 3406838. PMID 22753486.

- Godefroit, Pascal; Cau, Andrea; Dong-Yu, Hu; Escuillié, François; Wenhao, Wu; Dyke, Gareth (2013-05-29). "A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds". Nature. 498 (7454): 359–362. Bibcode:2013Natur.498..359G. doi:10.1038/nature12168. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 23719374.

- Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Pol, Diego (2019-12-11). "Probable basal allosauroid from the early Middle Jurassic Cañadón Asfalto Formation of Argentina highlights phylogenetic uncertainty in tetanuran theropod dinosaurs". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18826. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53672-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6906444. PMID 31827108.

- Razzolini, Novella L.; Oms, Oriol; Castanera, Diego; Vila, Bernat; Santos, Vanda Faria dos; Galobart, Àngel (2016-08-19). "Ichnological evidence of Megalosaurid Dinosaurs Crossing Middle Jurassic Tidal Flats". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 31494. Bibcode:2016NatSR...631494R. doi:10.1038/srep31494. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4990902. PMID 27538759.

- Allain, Ronan (2005). "The Postcranial Anatomy of the Megalosaur Dubreuillosaurus valesdunensis (Dinosauria Theropoda) from the Middle Jurassic of Normandy, France". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 850–858. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0850:tpaotm]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524511.

.jpg.webp)