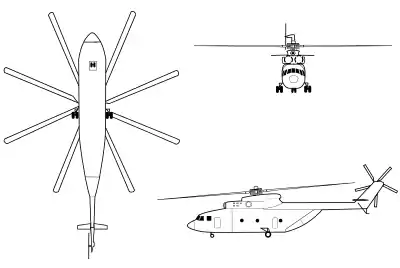

Mil Mi-26

The Mil Mi-26 (Russian: Миль Ми-26, NATO reporting name: Halo) is a Soviet/Russian heavy transport helicopter. Its product code is izdeliye 90. Operated by both military and civilian operators, it is the largest and most powerful helicopter to have gone into serial production.

| Mi-26 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Russian Air Force Mi-26 | |

| Role | Heavy lift cargo helicopter |

| National origin | Soviet Union/Russia |

| Manufacturer | Rostvertol |

| Design group | Mil Moscow Helicopter Plant |

| First flight | 14 December 1977 |

| Introduction | 1983 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Air Force Aeroflot Algerian Air Force Indian Air Force |

| Produced | 1980–present |

| Number built | 316 as of 2015 |

Design and development

Following the incomplete development of the heavier Mil Mi-12 (prototypes known as Mil V-12) in the early 1970s, work began on a new heavy-lift helicopter, designated as the Izdeliye 90 ("Project 90")[1] and later allocated designation Mi-26. The new design was required to have an empty weight less than half its maximum takeoff weight.[2] The helicopter was designed by Marat Tishchenko, protégé of Mikhail Mil, founder of the OKB-329 design bureau.[3]

The Mi-26 was designed to replace earlier Mi-6 and Mi-12 heavy lift helicopters and act as a heavy-lift helicopter for military and civil use, having twice the cabin space and payload of the Mi-6, then the world's largest and fastest production helicopter. The primary purpose of the Mi-26 was to transport military equipment such as 13-tonne (29,000 lb) amphibious armored personnel carriers and mobile ballistic missiles to remote locations after delivery by military transport aircraft such as the Antonov An-22 or Ilyushin Il-76.

The first Mi-26 flew on 14 December 1977[4] and the first production aircraft was rolled out on 4 October 1980.[1] Development was completed in 1983 and by 1985, the Mi-26 was in Soviet military and commercial service.[2]

The Mi-26 was the first factory-equipped helicopter with a single, eight-blade main lift rotor. It is capable of flight in the event of power loss by one engine (depending on aircraft mission weight) because of an engine load sharing system. While its empty weight is only slightly higher than the Mi-6's, the Mi-26 has a payload of up to 20 tonnes (44,000 lb). It is the second largest and heaviest helicopter ever constructed, after the experimental Mil V-12. The tail rotor has about the same diameter and thrust as the four-bladed main rotor fitted to the MD Helicopters MD 500.[5]

The Mi-26's unique main gearbox is relatively light at 3,639 kg (8,023 lb)[6] but can absorb 14,700 kilowatts (19,725 shp), which was accomplished using a non-planetary, split-torque design with quill shafts for torque equalization. The Mil Design Bureau designed the VR-26 transmission itself, due to Mil's normal gearbox supplier not able to design such a gearbox.[7] The gearbox housing is stamped aluminum.[6] A split-torque design is also used in the 5,670 kg (12,500 lb) gearbox assembly on the American three-engine Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion.[8]

As of 2016, the Mi-26 still holds the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale world record for the greatest mass lifted by a helicopter to 2,000 metres (6,562 ft) – 56,768.8 kilograms (125,000 lb) on a flight in 1982.[9]

In July 2010 a proposed Russian-Chinese development of a 33-ton heavy-lift helicopter was announced. In early 2019, Russia's state corporation Rostec inked a landmark agreement on developing a 40-ton next-generation heavy helicopter.

Rostvertol, the Russian helicopter manufacturer, was contracted to refurbish and upgrade the entire fleet of Mi-26s serving in the Russian Air Force, estimated to be around 20 helicopters. The upgraded aircraft is comparable to a new variant, the Mi-26T. Contract completion was planned for 2015. The contract also covered the production of 22 new Mi-26T helicopters. Eight new-built helicopters were delivered to operational units by January 2012.[10] Under the 2010 contract, 17 new-production helicopters were delivered by 2014.[11] In all, Rostvertol delivered fourteen Mi-26s to domestic and foreign customers in the period 2012‑14 and six helicopters in 2015.[12] Deliveries to the Russian Air Force were continued in 2016, 2017 and 2019.[13][14][15]

In 2016, Russia started development of PD-12V a variant of the Aviadvigatel PD-14 turbofan engine to power the Mi-26.[16]

Operational history

Buran programme

The developers of the Buran space vehicle programme considered using Mi-26 helicopters to "bundle" lift components for the Buran spacecraft, but test flights with a mock-up showed this to be risky and impractical.[17]

Chernobyl accident

The Mi-26S was a disaster response version hastily developed during the containment efforts of the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986.[18] Thirty Mi-26 were used for radiation measurements and precision drops of insulating material to cover the damaged No. 4 reactor. It was also equipped with a deactivating liquid tank and underbelly spraying apparatus. The Mi-26S was operated in immediate proximity to the nuclear reactor, with a filter system and protective screens mounted in the cabin to protect the crew during delivery of construction materials to the most highly contaminated areas.[19]

Siberian Woolly Mammoth recovery

In October 1999, an Mi-26 was used to transport a 25-ton block of frozen soil encasing a preserved, 23,000-year-old woolly mammoth (Jarkov Mammoth) from the Siberian tundra to a lab in Khatanga, Taymyr. Due to the weight of the load, the Mi-26 had to be returned to the factory afterward to check for airframe and rotor warping caused by the potential of structural over-stressing.[3]

Afghanistan Chinook recovery

In early 2002, a civilian Mi-26 was leased to recover two U.S. Army MH-47E Chinook helicopters from a mountain in Afghanistan. The Chinooks, operated by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, had been employed in Operation Anaconda, an effort to drive al Qaeda and Taliban fighters out of the Shahi-Kot Valley and surrounding mountains. They found themselves stranded on the slopes above Sirkhankel at altitudes of 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) and 3,100 metres (10,200 ft). While the second craft was too badly damaged to recover, the first was determined to be repairable and estimated to weigh 12 tonnes (26,000 lb) with fuel, rotors, and non-essential equipment removed. That weight exceeded the maximum payload of 9.1 tonnes (20,000 lb) at an altitude of 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) of the U.S. military's Sikorsky CH-53E.[3]

The Mi-26 was located through Skylink Aviation in Toronto, which had connections with a Russian company called Sportsflite that operated three civilian Mi-26 versions called "Heavycopters". One of the aircraft, aiding in construction and firefighting work in neighboring Tajikistan, was leased for $300,000; it lifted the Chinook, flew it to Kabul, then later to Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan to ship to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, U.S. for repairs. Six months later, a second U.S. Army CH-47 that had made a hard landing 160 kilometres (100 mi) north of Bagram at an altitude of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) was recovered by another Sportsflite-operated Mi-26 Heavycopter.[3]

Chechnya crash

On 19 August 2002, Chechen separatists hit an overloaded Mi-26 with a surface-to-air missile, causing it to crash-land in a minefield, killing 127 of the people on board.[20]

China, Wenchuan "quake lake" emergency

As a result of the magnitude 8.0 earthquake in Sichuan province of China on 12 May 2008, many rivers became blocked by landslides, resulting in the formation of so-called quake lakes: large amounts of water pooling up behind the landslide-formed dams. These dams eventually broke under the weight of the water,[21] endangering those downstream. At least one Mi-26 belonging to a branch of China's civil aviation service was used to bring heavy earth moving tractors to the quake-lakes at Tangjiashan mountain, located in difficult terrain and accessible only by foot or air.[22]

Afghanistan helicopter downing

In July 2009, a Moldovan Mi-26 was shot down in Helmand province with the loss of six Ukrainian crew members. The aircraft, belonging to Pecotox Air, was said to be on a humanitarian mission under NATO contract.[23]

Indian Air Force Mi-26 crash

On 14 December 2010, an Indian Air Force Mi-26 crashed seconds after taking off from Jammu Airport, injuring all nine passengers. The aircraft fell from an altitude of about 15 metres (50 ft).[24] The Indian Institute of Flight Safety released an investigation report that stated improper fastening of the truck inside caused an imbalance of the helicopter and led to the crash. The Mi-26 had been carrying machines from Konkan Railway to Jammu–Baramulla line project.[25][26]

Norwegian Air Force Sea King recovery

On 11 December 2012, a Westland Sea King from No. 330 Squadron RNoAF experienced undisclosed technical issues and made an emergency landing on Mount Divgagáisá. The landing caused parts of the landing gear to break. The Sea King was prepared by removing rotor blades and fuel before it was airlifted to Banak Air Station by a Russian Mil Mi-26 on 23 December 2012.[27]

Variants

_192.jpg.webp)

- V-29

- Prototype version

- Mi-26

- Military cargo/freight transport version.[28] NATO name: 'Halo-A'.

- Mi-26A

- Upgraded military version with a new flight/navigation system. Flown in 1985 but no production.[28]

- Mi-26M

- Upgraded version of the Mi-26 with ZMKB Progress D-127 engines for better performance.[29]

- Mi-26S

- Disaster response version developed in response to nuclear accident at Chernobyl.[28]

- Mi-26T

- Basic civil cargo/freight transport version. Production from 1985.[28]

- Mi-26TS

- Civil cargo transport version, also marketed as Mi-26TC.[28]

- Mi-26TM

- Flying crane version with under-nose gondola for pilot/crane operator.[28]

- Mi-26TP

- Firefighting version with internal 15,000 litres (4,000 US gal; 3,300 imp gal) fire retardant tank.[28]

- Mi-26MS

- Medical evacuation version of Mi-26T. Up to 60 stretcher cases in field ambulance role, or can be equipped for intensive care or as field hospital.[28]

- Mi-26P

- 63 seat passenger version.[28]

- Mi-26PK

- Flying crane derivative of Mi-26P.[28]

- Mi-26T2

- Improved version of the Mi-26T equipped with BREO-26 airborne electronic system, allowing it to fly any time, day or night, under good and bad weather conditions. Serial production began on May 22, 2015.[30]

- Mi-26T2V

- Newest modernization variant intended for the Russian military, equipped with new NPK90-2V avionics suite allowing it to fly routes in automatic mode, airborne defense complex "Vitebsk", anti-blast seats and new navigation and satellite communication systems. The cockpit is fitted with multifunctional displays with provision for use of night-vision goggles during night ops. The Mi-26T2V made its maiden flight in August 2018.[31][32]

- Mi-27

- Proposed airborne command post variant; two prototypes built.

Operators

Military operators

- Equatorial Guinean Air Force[33]

_RP10149.jpg.webp)

Civil operators

.jpg.webp)

Specifications (Mi-26)

Data from Jane's All the World's Aircraft 2003–2004[28]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5 (2 pilots, 1 navigator, 1 flight engineer, 1 flight technician)

- Capacity:

- 90 troops or 60 stretchers

- 20,000 kg (44,000 lb) cargo

- Length: 40.025 m (131 ft 4 in)

- Height: 8.145 m (26 ft 9 in)

- Empty weight: 28,200 kg (62,170 lb)

- Gross weight: 49,600 kg (109,349 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 56,000 kg (123,459 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × ZMKB Progress D-136 turboshaft engines, 8,500 kW (11,400 hp) each

- Main rotor diameter: 32 m (105 ft 0 in)

- Main rotor area: 804.25 m2 (8,656.9 sq ft)

- Blade section: root: TsAGI 12%; tip: TsAGI 9%[50]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 295 km/h (183 mph, 159 kn)

- Cruise speed: 255 km/h (158 mph, 138 kn)

- Range: 500 km (310 mi, 270 nmi) with 7,700 kg (17,000 lb) cargo

- Ferry range: 1,920 km (1,190 mi, 1,040 nmi) (with auxiliary tanks)

- Service ceiling: 4,600 m (15,100 ft)

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

- Citations

- Gordon, Yefim; Dmitry and Sergey Komissarov (2005). Mil's Heavylift Helicopters. Hinkley: Midland Publishing. pp. 75–96. ISBN 1 85780 206 3.

- Donald, David, ed. (1997). The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Barnes & Noble Books. p. 640. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- Croft, John (July 2006). "We Haul It All". Air & Space. 21 (2): 28–33. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- Jackson 2003, p. 392.

- Watkinson, John. "Art of the Helicopter" p171. Butterworth-Heinemann, 28 January 2004. ISBN 0750657154, 9780750657150. Retrieved: 5 August 2012.

- Lev I. Chaiko (1990) Review of the Transmissions of the Soviet Helicopters Archived 16 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine pages 2, 3, 9. Glenn Research Center/NASA Technical Memorandum 10363

- Smirnov, G. "Multiple-Power-Path Nonplanetary Main Gearbox of the Mi-26 Heavy-Lift Transport Helicopter", Vertiflite March/April 1990, pp. 20–23

- Parker, Andrew. "CH-53K King Stallion Inches Closer to Sunrise Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine" Aviation Today, 6 May 2014. Accessed: 7 May 2014.

- "FAI Record ID #9936 – Helicopters, Greatest mass carried to height of 2 000 m Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale Record date 3 February 1982. Accessed: 1 August 2016.

- "Russian Air Force takes delivery of two new Mi-26 Halos". Air Forces Monthly (286): 28. January 2012.

- "Mi-26T2 production kicks off" Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Take Off, 2014.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / «Роствертол» поставит более 120 вертолетов Ми-28 и Ми-35 в 2016–2018 гг". www.armstrade.org. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- July 24, Russian Defense Policy; Reply, 2017 at 7:36 pm (24 July 2017). "This Week's MOD Graphic". russiandefpolicy.blog. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Завершена приемка транспортного вертолета Ми-26Т для авиасоединения ВВО в Хабаровском крае". armstrade.org. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- http://www.armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2019/1025/160555031/detail.shtml

- "New Engines For Russia's Heavy-lift Helicopter". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Dr. Fedotov, V.A. "BURAN Orbital Spaceship Airframe Creation". Buran Energia. Archived from the original on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Archived 4 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Mil Moscow Helicopter Plant

- Masharovsky, Maj.Gen. M. (October 1998). "Operation of Helicopters During the Chernobyl Accident" (PDF). NATO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "Chechen gets life for air attack" Archived 17 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine. BBC news, 29 April 2004.

- Swollen lake tops China's quake relief agenda, draining, evacuation side by side Archived 11 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Xinhua, 2008-05-28.

- Copters take off to large Sichuan "quake lake" Archived 30 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. chinadaily.com.cn, 2008-05-24.

- "Six Ukrainians die in Afghan chopper crash". Television New Zealand. Reuters. 15 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- "IAF chopper crashes in Jammu, 9 injured". The Times of India. 15 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- "IAF helicopter crashes in Jammu, all safe" Archived 4 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. NDTV, 14 December 2010. Retrieved: 23 July 2012.

- "IAF Chopper Crashes, Leaves 9 Injured". Outlook India, 14 December 2010. Retrieved: 23 July 2012.

- NRK. "Gigahelikopter skal redde Sea King". NRK. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Jackson 2003, pp. 393–394.

- Taylor, John W. R. (March 1995). "Mil Mi-26 (NATO 'Halo')". Gallery of Russian Aerospace Weapons. Air Force Magazine. Vol. 78 no. 3. Air Force Association. p. 65.

- "ТАСС: Армия и ОПК – "Вертолеты России" начали серийное производство тяжелого Ми-26Т2". ТАСС. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ""Вертолеты России" впервые представят на "Армии-2018" модернизированный Ми-26Т2В". russianhelicopters.aero. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "Army 2018: Russian Helicopters unveils Mi-26T2V". Jane's Information Group. 24 August 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "World Air Forces 2018". Flightglobal Insight. 2018. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "World Air Forces 2008". Flightglobal Insight. 2013. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies: The Military Balance 2014, p.233

- Najib, Mohammed (25 January 2018). "Jordan receives first Mi-26T2". IHS Jane's 360. Ramallah. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Largest airlift helicopter MI-26T2 joins RJAF". The Jordan Times. Amman. 17 January 2018. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "الأردن يتسلم أضخم طائرة نقل عمودية من روسيا- arabic.china.org.cn". arabic.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Jordan receives second Mi-26 heavy-lift helo - Jane's 360". www.janes.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- http://airrecognition.com/index.php/news/defense-aviation-news/2020/january/5800-jordan-received-two-mi-26t2-helicopters-from-russia.html

- "World Air Forces 2020". Flight Global. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/12" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "Ejercito del Peru Mi-26 Halo". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Mladenov Air International May 2011, p. 112.

- "Skytech Fleet". skytech-helicopters.eu. Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "Massive helicopter used in wildfire on Russia/China border". fireaviation.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- "UT air Mil Mi-26". heli.utair.ru. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "Aeroflot Mil-Mi-26". Demand media. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "World's Air Forces 1987 pg. 85". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Bibliography

- Croft, John (July 2006). "We Haul It All". Air & Space. 21 (2): 28–33. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- Donald, David, ed. (1997). The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Barnes & Noble Books. p. 640. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- Gordon, Yefim; Dmitry and Sergey Komissarov (2005). Mil's Heavylift Helicopters. Hinkley: Midland Publishing. pp. 75–96. ISBN 1 85780 206 3.

- Jackson, Paul (2003). Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group. ISBN 0-7106-2537-5.

- Mladenov, Alexander (May 2011). "Fighting Terrorism & Enforcing the Law in Russia". Air International. Vol. 80 no. 5. pp. 108–114. ISSN 0306-5634.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mil Mi-26. |