Military of the Ashanti Empire

The Ashanti Empire (Asante Twi: Asanteman) was an Akan empire and kingdom from 1701 to 1957, in modern-day Ghana. The military of the Ashanti Empire first came into formation around the 17th century AD in response to subjugation by the Denkyira Kingdom.[3] It served as the main armed forces of the empire until it was dissolved when the Ashanti became a British crown colony in 1901.[4] In 1701, King Osei Kofi Tutu I won Ashanti independence from Denkyira at the Battle of Feyiase and carried out an expansionist policy, absorbing many tribes and creating one of the most formidable empires during the modern age.[5]

| Ashanti army | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leaders | Asantehene (commander-in-chief) |

| Headquarters | Kumasi |

| Active regions | Gold Coast, Ivory Coast, Togo, Dahomey |

| Size | capable of 200,000 men.[1][2] |

| Part of | Ashanti Empire |

| Allies | The Dutch, Akwamu, Dagbon |

| Opponents | Denkyira, Fante Confederacy, Ga-Adangbe alliances, Akyem, Kingdom of Dahomey, the Danes and British Empire. |

| Battles and wars | Battle of Feyiase, Battle of Nsamankow, Battle of Atakpamé, War of the Golden Stool |

History

The Ashanti originally centered on clans which were headed by a paramount chief or Amanhene. The clans did not have a standing and organized army that operated on a centralized chain of command.[6][7] The Ashanti clans became tributaries of another Akan state, Denkyira who exerted influence over much of the Gold Coast. In the mid-17th century the Oyoko, an Ashanti clan which was led by Chief Nana Oti Akenten, started consolidating with the other Ashanti clans into a loose confederation against the Denkyira gradually strengthening and improving the armies of the clans.[8]

War of Independence

In the 1670s the head of the Oyoko clan and successor to Nana Akenten, Osei Kofi Tutu I, began another rapid consolidation of Akan clans. He sought cooperation via diplomacy and warfare.[9] King Osei Kofu Tutu I and his chief advisor, Okomfo Anokye led a coalition of influential Ashanti city-states against their common enemy, the Denkyira. With a larger and better organized army, the United Ashanti Kingdom defeated the Denkyira at the Battle of Feyiase, proclaiming its independence in 1701. Osei Tutu through diplomacy and warfare induced the leaders of the other Ashanti city-states to declare allegiance and adherence to Kumasi, the Ashanti capital. Thus, forming a united kingdom instead of a confideracy. King Osei Tutu and his adviser Anokye, followed an expansionist policy to absorb other kingdoms and increase the status of the Ashanti kingdom into an empire.[5]

Reforms under Osei Tutu I

Osei Tutu centralized the loose confideration of Alan states in order to organize and professionalize the military. He also expanded the powers of the Judiciary system within the Centralized government. Eventually, the loose confideration of small city-states unified as a kingdom and grew into an empire. Newly conquered areas had the option to either join the Ashanti Empire or become tributary states.[10]

Osei Tutu placed strong emphasis on the military organization of the Akan Union states prior to the war with Denkyira. He adopted the military organization of Ashanti allies, Akwamu, and honed the Union army into an effective fighting unit.[11] Osei Tutu improved the battle strategy of the union army through the introduction of the pincer formation whereby soldiers attacked from the left, right and rear. This formation was later adopted by several other kingdoms in the Gold Coast. The Ashanti military declined in 1901 after the empire was defeated by the British following the War of the Golden Stool.

Organization

The Asantehene was the commander-in-chief of the Ashanti military.[12] The army of the Ashanti Empire was organized into 6 parts. Each had various sub divisions. The organization of the Ashanti army was based on local Akan military systems such as the organization of the Akwamu army. Ashanti military systems were independent of European military forms.[13] The six parts of the Ashanti army were:

- Scouts (akwansrafo),

- Advance guard (twafo)

- Main body (adonten),

- Personal bodyguard (gyase)

- Rear- guard (kyidom)

- Two wings-left (benkum) and right (nifa). Each wing having two formations: right and right-half (nifa nnaase), left and left-half (benkum nnaase)

In battle, the army used advanced guard, main body, rear guard and right and left wings on the move. This organization enabled the Ashanti generals to maneuver their forces with flexibility. Reconnaissance and pursuit operations were carried out by the scouts. The advanced guard could also serve as initial storm troops or bait troops to get the enemy to reveal their position and strength. The gyaase or personal guards protected the king or high ranking nobles on the battlefield. The rear guard however, might function for pursuit or as a reserve echelon. The two wings aided in the tactics of the Ashanti during battle through the encirclement of the opposing force or striking at the rear.[14]

Individualized acts of daring were encouraged, such as rushing out into the open to chop off the heads of dead or wounded enemies. A tally of these trophies was presented to the commanding general after the end of the engagement.[15] There was in existence severe discipline in the Ashanti army. Soldiers who showed cowardice or indiscipline were whipped with heavy swords carried by special continents of enforcer troops known as the Sword bearers. Ashanti soldiers had to memorize the following saying: "If I go forward, I die; if I flee, I die. Better to go forward and die in the mouth of battle." Enforcers were mostly deployed forward between the scouts and the main force but eased back during battle to observe faltering soldiers.[16]

The ankobia or special police functioned as special forces and bodyguards to the Asantehene. They served as a source of intelligence for suppressing rebellion.[17] It is unknown if the Ashanti had cavalry like other West African kingdoms however, horses were introduced in the kingdom around the 18th century. Mounted horses occasionally feature among the small brass sculptures used as gold weights in the Ashanti Empire.[18] Canoes and wooden ferries were used for troop transport. British captain, Brackenbury described an amphibious landing of Ashanti troops in the late 19th century on Assin. He estimated that two ferries of boats crossed the River Pra with 12,000 men in five days with 30 men per boats and four trips an hour. [19] In a feature seldom seen among African armies, the Ashanti also deployed units of medical personnel behind the main forces, who were tasked with caring for the wounded and removing the dead.[20]

Mobilization, recruitment and logistics

A small core of professional warriors was supplemented by peasant levies, volunteers and contingents from allied forces or tributary kingdoms. Grouped together under competent commanders such as Osei Tutu and Opoku Ware, such hosts began to expand the Ashanti empire in the 18th century on into the 19th, moving from deep inland to the edges of the Atlantic. One British source in 1820 estimated that the Ashanti could field into battle a potential 80,000 troops, and of these, 40,000 could in theory, be outfitted with muskets or blunder-busses.[21]

Infrastructure such as road transport and communication throughout the empire was maintained via a network of well-kept roads from the Ashanti mainland to the Niger river and other trade cities.[17][22]

Equipment

Arms

Before the unification of the Ashanti clans as one kingdom and empire, the bow, shield and arrow were the weapon of choice. The Ashanti became familiar with fire arms in the 18th century. By the 19th century, majority of the Ashanti troops were armed with a variety of guns. This includes the standard European trade muskets "Long Dane". However, Ashanti guns were obsolete compared to first rank European firearms. General Nkwanta, head of the Ashanti army's general council is reported to have done a detailed assessment of new breech-loading European firearms in 1872–73 and was alarmed by the obsolescence of Ashanti muskets in comparison to their European counterparts. Good quality powder was in short supply. Also, Most of the gunmen did not use wadding to compact the powder down into the barrels but simply dumped in it while adding a variety of lead slugs, nails, bits of metal or even stones. This made an impressive pyrotechnic display, but demanded opponents to be in close range.[23]

Available guns as well as pouches for ammunition were carefully protected with leopard or leather skin covers. Soldiers carried thirty to forty gunpowder charges within reach, which was individually packed in small wooden boxes for quick loading. The buckskin belt worn by the soldiers provided alternate weapons such as several types of knives and machete.[15] Blunderbuss also formed part of Ashanti weapon arsenal.[24][25]

Artillery

The Ashanti obtained some cannons from the Dutch but only mounted them at important and sacred places in the capital, Kumasi, and other Ashanti cities.[26] [27] Ashanti king, Kwaku Dua signed a military agreement which involved the yearly supply of Ashanti troops to the Dutch army in exchange for Dutch artillery pieces. The Dutch suppliers provided the Ashanti king with immobile cannons on ships rather than field carriages.[28] There existed in Kumasi, a Cannon-square that housed a trophy of Dutch Cannons.[29]

Akrafena

The Akrafena is an Ashanti sword, originally meant for warfare. It served as an alternative to the Ashanti guns.[30] Other Ashanti war swords included;[31]

• Afenatene: It was used by the Ashantis to penetrate the hearts of war opponents. The design of the sword is different from an Akrafena as it contains sculpt art of the akoma (heart), denkyem (crocodile), akuma (axe) and the sankofa on the blade.

• Afenanta: The Afenanta is a "Double Blade Sword" used by the Ashanti in warfare, primarily for cutting human ligaments during battle.

Akrafena martial art

There existed schools that taught the techniques of the Ashanti swords in the past. The schools still hold the genuine Ashanti Swords techniques in modern Ghana.[32] According to Davidson, there were 20 fighting postures in training; The Ashanti people practitioners of the past generally used low kicking techniques to distract, dismantle and disable the opponent when holding the sword in one hand and sheath in the other. The sword-based fighting techniques are similar in part to that of Eskrima whiles the combat hand-techniques as well as the kicking techniques are similar in part to that of Wing Chun.[32]

Battle tactics

The Ashanti tactical system was decentralized in order to suit the thick forest terrain of West Africa. The growth of jungles often hindered large scale clashes involving thousands of soldiers in the open. Ashanti tactical methods involved smaller sub units, constant movement, sub movement, ambushes and more dispersed strikes and counter-attacks. In one unusual incident in 1741 however, the armies of Asante and Akyem agreed to "schedule" a battle while they jointly assigned some 10,000 men to cut down trees to make space for a full scale clash. The Asante won this encounter.[33]

A British commentary in 1844 claimed Ashanti tactics involved cutting a number of footpaths in the bush in order to approach and encircle the enemy force. The Ashanti army formed in line and attacked the enemy upon reaching the initial jump-off point. Other British accounts describe the use of converging columns by the Ashanti army whereby several marching parallel columns joined into one general strike force, maneuvering before combat. The converging volume strategy was used by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Napoleonic Wars as well as the British in their war with the Ashanti.[20] The 'march divided, fight together' was the original raison d'etre of the division. These standardized tactics had often yielded the Ashanti victory. Scouts screened the army of the enemy as it marched in its columns, then withdrew as the enemy became close. At the beginning of combat, the advance guard moved up in 2 or 3 lines, discharged its muskets and paused to reload. The second line would then advance to fire and reload. A third rear line would then repeat the advance – fire-reload cycle. This "rolling fire" tactic was repeated until the advance halted. Flanking units were also dispatched as part of the fire and maneuver model.

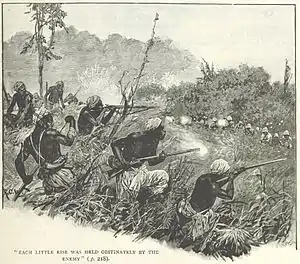

The Ashanti also used hammer and anvil tactics in wars such as the third Anglo-Ashanti war. In 1874 a strong British force under Sir Garnet Wolseley, armed with modern rifles and artillery, invaded the territory of the Ashanti Empire. The Ashanti did not confront the invaders immediately, and made no major effort to interdict their long, vulnerable lines of communication through the jungle terrain. Their plan appeared to be to draw the British deep into their territory, against a strong defensive anvil centred at the town of Amoaful. Here the British would be tied down, while manoeuvring wing elements circled to the rear, trapping and cutting them off. Some historians (Farwell 2001) note that this was approach was a traditional Ashanti battle strategy, and was common in some African armies as well.[34] At the village of Amoaful, the Ashantis succeeded in luring their opponents forward, but could not make any headway against the modern firepower of the British forces, which laid down a barrage of fire to accompany an advance of infantry in squares. This artillery fire took a heavy toll on the Ashanti, but they left a central blocking force in place around the village, while unleashing a large flanking attack on the left, that almost enveloped the British line and successfully broke into some of the infantry squares. Ashanti weaponry however, was poor compared to the modern weapons deployed by the redcoats, and such superior arms served the British well in repulsing the dangerous Ashanti encirclements.[35] As one participant noted:

- "The Ashantees stood admirably, and kept up one of the heaviest fires I ever was under. While opposing our attack with immediately superior numbers, they kept enveloping our left with a constant series of well-directed flank attacks."[36]

Wolesey had studied and anticipated the Ashanti "horseshoe" formations, and had strengthened the British flanks with the best units and reinforced firepower. He was able to shift this firepower to threatened sectors to stymie enemy maneuvers, defeating their hammer and anvil elements and forcing his opponents to retreat.[37] One British combat post-mortem pays tribute to the slain Ashanti commander for his tactical leadership and use of terrain:

- "The great Chief Amanquatia was among the killed. Admirable skill was shown in the position selected by Amanquatia, and the determination and generalship he displayed in the defence fully bore out his great reputation as an able tactician and gallant soldier."[38]

Siege and engineering

In one siege of a British Fort during the Anglo-Ashanti wars, the Ashanti sniped at the defenders, cut the telegraph wires as a means of curbing communication, blocked food supplies, and attacked relief columns.[39] The Ashanti Empire built powerful log stockades at key points. This was employed in later wars against the British to block British advances. Some of these fortifications were over a hundred yard long, with heavy parallel tree trunks. They were impervious to destruction by artillery fire. Behind these stockades numerous Ashanti soldiers were mobilized to check enemy movement. While formidable in construction, many of these strongpoints failed because Ashanti guns, gunpowder and bullets were poor, and provided little sustained killing power in defense. Time and time again British troops overcame or bypassed the stockades by mounting old-fashioned bayonet charges, after laying down some covering fire.[40]

Brass barrel blunderbuss were produced in some states in the Gold Coast including the Ashanti Empire around the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Various accounts indicate that Asante blacksmiths were not only able to repair firearms, but that barrels, locks and stocks were on occasion remade.[25]

See also

References

- Vandervort (1998).

- "News.google.com: The Newfoundlander - Dec 16, 1873". Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "Ghana - THE PRECOLONIAL PERIOD". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ’The Location of Administrative Capitals in Ashanti, Ghana, 1896-1911’ by R. B. Bening in The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1979) pg. 210

- History of the Ashanti Empire. Archived 2012-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Kings And Queens Of Asante Archived 2012-10-30 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ashanti.com.au Our King - Nana Kwaku Dua is now Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, Asanthene". Archived from the original on 2005-12-11. Retrieved 2005-12-11.

- "Ghana - THE PRECOLONIAL PERIOD". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, New York: St. Martin's, 1995 (1989), p. 194.

- Giblert, Erik Africa in World History: From Prehistory to the Present 2004

- William Tordoff (1962). "The Ashanti Confederacy". The Journal of African History. 3 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1017/S0021853700003327.

- Seth Kordzo Gadzekpo (2005). History of Ghana: Since Pre-history. Excellent Pub. and Print. p. 91–92. ISBN 9988070810. Retrieved 2020-12-27 – via Books.google.com.

- William Tordoff (1962). "The Ashanti Confederacy". The Journal of African History. 3 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1017/S0021853700003327.

- Charles Rathbone Low, A Memoir of Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet J. Wolseley, R. Bentley: 1878, pp. 57–176

- The British Critic, Quarterly Theological Review, and Ecclesiastical Record, Published 1834, Printed for C. & J. Rivington, and J. Mawman, p. 165-172. Can be found on Google Books.

- The Victorians at war, 1815–1914: an encyclopedia of British military history. By Harold E. Raugh. ACL-CLIO: pp. 21–37

- Davidson (1991), p. 240.

- Law, Robin (1980). The Horse in West African History: The Role of the Horse in the Societies of Pre-colonial West Africa. 1. International African Institute. p. 16. ISBN 9780197242063.

- C. Henry Brackenburg (1874), p. 56.

- Vandervort, pp. 16–37

- Kwame Arhin (1967). "The Financing of the Ashanti Expansion (1700–1820)". Journal of the International African Institute. 37 (3): 283–291. doi:10.2307/1158151. JSTOR 1158151.

- Collins & Burns (2007), pp. 140–141

- Vandervort, pp. 61–72

- Kwame Arhin (1967). "The Financing of the Ashanti Expansion (1700–1820)". Journal of the International African Institute. 37 (3): 283–291. doi:10.2307/1158151. JSTOR 1158151.

- Kea, R. A. (1971). "Firearms and Warfare on the Gold and Slave Coasts from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries". The Journal of African History. 12 (2): 185–213. doi:10.1017/S002185370001063X. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180879.

- C. Henry Brackenburg (1874).

- William Blackwood (1953).

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 198.

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 384.

- Fraser, Douglas (2004). African Art and Leadership. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780299058241.

- Collins and Burns (2007), p. 140.

- Davidson (1991), p. 242.

- J. R. McNeill (2004). "Environmental History". Environmental History. 9 (3): 388–410. doi:10.2307/3985766. JSTOR 3985766.

- Byron Farwell. 2001. The encyclopedia of nineteenth-century land warfare. WW Norton. p 56.

- The Victorians at war, 1815–1914: an encyclopedia of British military history. By Harold E. Raugh. ACL-CLIO: pp. 21–37

- Charles Rathbone Low, A Memoir of Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet J. Wolseley, R. Bentley: 1878, pp. 57–176

- The Victorians at war, 1815–1914: pp. 21–37

- Charles Rathbone. A Memoir of Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet J. Wolseley. 1878, pg 174

- Robert B. Edgerton (2010).

- The Ashanti campaign of 1900, (1908) By Sir Cecil Hamilton Armitage, Arthur Forbes Montanaro, (1901) Sands and Co. pgs 130–131

Bibliography

- Vandervort, Bruce Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830–1914, Indiana University Press: 1998 ISBN 0253211786

- Basil, Davidson African Civilization Revisited, Africa World Press: 1991 ISBN 9780865431232

- Collins, Robert O.; Burns, James M. (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521867467.

- C. Henry, Brackenbury The Ashanti War (1874) Volume 1: A Narrative, Andrews UK Limited: 2012 ISBN 9781781508992

- William, Blackwood Blackwood's Magazine, Volume 273, William Blackwood: 1953

- Ivor Wilks (1989). Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521379946. Retrieved 2020-12-29 – via Books.google.com.

- Edgerton, Robert B. (2010). The Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred-Year War For Africa's Gold Coast. ISBN 9781451603736.