Mirza Ghulam Murtaza

Mirza Ghulam Murtaza (Urdu: مرزا غلام مرتضى) (c.1791 – June 1876) was an Indian nobleman, chief, military officer and physician, best known for being the father of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement. He belonged to a family of landed aristocracy within the Mughal Empire that lost most of its estate to the Sikh Kingdom during the late 18th century and only a fraction of which – including Qadian, the family’s ancestral seat – he was able to regain from it.[1] He was mentioned in some detail by Sir Lepel Griffin in The Panjab Chiefs, a survey of the Punjab’s aristocracy.[2] Ghulam Murtaza was married to Chiragh Bibi and had three surviving children.[3]

Ghulam Murtaza | |

|---|---|

| Mīrzā Raʾīs-i Qādiyān | |

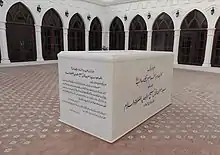

Tomb of Mirza Ghulam Murtaza at Qadian. | |

| Landed gentry | |

| Predecessor | Mirza Atta Muhammad |

| Successor | Mirza Ghulam Qadir |

| Born | c. 1791 |

| Died | June 1876 |

| Buried | Qadian, Punjab, India |

| Noble family | Barlas |

| Spouse(s) | Chiragh Bibi |

| Issue | |

| Father | Mirza Atta Muhammad |

| Occupation | Rais, physician, military personnel |

Chief of Qadian

Mirza Ghulam Murtaza was the son of Mirza Atta Muhammad, the chieftain (Raʾīs) of the fortified village of Qadian. His predecessors had originally exercised authority over a large semi-independent territory of some sixty square miles[4] comprising over seventy villages neighbouring Qadian[5] and had quasi-familial ties with the Mughal emperors. Atta Muhammad was entitled to a seat at the Durbars (courts) of the Mughal emperor.[6] His grandfather, Mirza Faiz Muhammad was conferred the title of Azādud Daulah (Strong Arm of the Government) by the emperor Farrukhsiyar and the rank of Haft Hazārī enabling him to keep a regular force of 7,000 soldiers.[7]

With the insurgency of the Sikh Confederacy, however, during the 18th century, the decline of the Mughals, and lacking any practical support from Delhi, the family saw a steady loss of its estate until, by the time of Atta Muhammad’s death, Qadian, the last remaining stronghold, had also come under the control of the Sikhs and merged within the Sikh Empire. The family was expelled and lived in a nearby village for sixteen years until, in 1818, Ghulam Murtaza was allowed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh to return to Qadian in exchange for military support. This he did by joining, alongside his brothers, Ranjit Singh's army and engaging in campaigns in several places. In 1834–5, a further five villages out of his ancestral estate were returned to him by Ranjit Singh.[8] During the Anglo-Sikh wars, the family remained loyal to the Sikhs.[9] The wars ended, however, with a British victory resulting in the dissolution of the Sikh Empire and bringing the Punjab under British control in 1849. During the last days of the Sikh rule an abortive effort was made by some Sikhs to kill Ghulam Murtaza and his brother Mirza Ghulam Muhyuddin in Basrawan near Qadian where the two had been confined by them, but they were eventually rescued by their younger brother Mirza Ghulam Haidar.[10]

Although the Punjab remained relatively peaceful during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Muslims of the region joined the Sikhs and the Muslim tribesmen of Kohat in providing military support to the British.[11] During the conflict, Ghulam Murtaza and his brother also supported the British by supplying horses and enlisting fifty Sowars (mounted troopers) in the British forces at their own expense.[9][12] Ghulam Ahmad and later Ahmadi authors viewed support for British rule during this period as a more favourable option for Muslims of the Punjab in contrast to the Sikh rule that preceded it.[13][14]

Subsequently, Ghulam Murtaza spent much of his time and fortune trying to regain his properties through litigation in the Colonial courts but to no avail.[15] The British accepted his claim over Qadian and some neighboring villages, but expropriated the rest of the family's ancestral estates.[16][4] Various British generals commended, through letters, the role of Ghulam Murtaza and his brother in helping put down the rebellion[9] and the British Government granted him an annual pension of 700 rupees.[4][17]

Military career

Mirza Ghulam Murtaza | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Sikh Army |

| Years of service | between 1818 and 1849 |

| Rank | Commander |

Ghulam Murtaza fought in several places including Kashmir, Peshawar and Multan.[18] Ranjit Singh annexed Kashmir in 1819 following the Battle of Shopian and his forces took Peshawar in 1823 at the Battle of Nowshera,[8] though Ghulam Murtaza's role in these battles is unclear. In the reign of Sher Singh, he was in the army command structure. In 1841, with a general he was sent to Mandi and the Kullu Valley. In 1843, he was the commander of an infantry regiment which was sent to Peshawar. He also fought in Hazara in 1848 and was successful in putting down a rebellion. He also sent his men under his brother's command and quickly gained a good reputation as an able chief and commander.

Family and personal life

Mirza Ghulam Murtaza’s ancestors shared tribal affiliation with the Mughal rulers of the Indian subcontinent. He had four brothers: Mirza Ghulam Muhammad; Mirza Ghulam Mustafa; Mirza Ghulam Muhyuddin; and Mirza Ghulam Haidar. He was married to Chiragh Bibi, the sister of Mirza Jami'at Baig of Aima, a village in Hoshiarpur. They had six or seven children (exact count unsure) several of whom died in infancy. The names of the surviving children were: Murad Begum (daughter); Mirza Ghulam Qadir (son); and Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (son). Ghulam Ahmad was born a twin with a sister named Jannat who died a few days after birth.[3]

Ghulam Murtaza was also a notable physician, having studied medicine at Baghbanpura and Delhi,[19] but accepted no payment for his medical treatments.[9] He once declined an offer of an award comprising the rents of two villages by the chief of Batala in return for his medical services on the grounds that the two villages once belonged to his ancestral estate and could not be accepted in this way.[20] He was also a poet using as his nom de plume (takhallus) the name Tahsin.[21] In his last days he built the Aqsa mosque which was oversized at the time and directed in his will that he be buried in a corner of its courtyard where his grave can still be found today.[22]

Notes

- Khan 2015, pp. 22–23.

- Sir Lepel H. Griffin (1865), The Panjab Chiefs, Online: apnaorg.com. pp.381-2

- Dard 2008, p. 33.

- Adamson 1989, p. 14.

- Khan 2015, p. 22.

- Adamson 1989, p. 13.

- Dard 2008, p. 9.

- Dard 2008, pp. 13–14.

- Adamson 1989, p. 15.

- Dard 2008, p. 15.

- Hardy 1972, p. 67.

- Dard 2008, pp. 17–20.

- Geaves 2018, pp. 28–9.

- Lavan 1974, pp. 23–4.

- Dard 2008, p. 23.

- Griffin & Massy 1890, p. 50.

- Friedmann 2003, p. 2.

- Dard 2008, pp. 13–16.

- Dard 2008, p. 20.

- Adamson 1989, p. 18.

- Dard 2008, pp. 22.

- Dard 2008, pp. 22–24.

References

- Adamson, Iain (1989). Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian. Elite International Publications. ISBN 1-85372-294-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dard, A.R. (2008). Life of Ahmad: Founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement (PDF). Tilford: Islam International. ISBN 978-1-85372-977-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedmann, Yohanan (2003). Prophecy Continuous: Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-566252-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geaves, Ron (2018). Islam and Britain: Muslim Mission in an Age of Empire. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-7173-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffin, Lepel H.; Massy, Charles Francis (1890). The Panjab Chiefs. Lahore: Civil and Military Gazette Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hardy, Peter (1972). The Muslims of British India. London: cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01529-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khan, Adil Hussain (2015). From Sufism to Ahmadiyya: A Muslim Minority Movement in South Asia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01529-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lavan, Spencer (1974). The Ahmadiyah movement: a history and perspective. Delhi: Manohar Book Service.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)