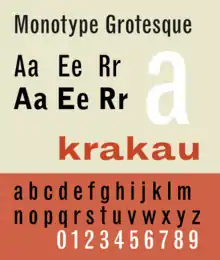

Monotype Grotesque

Monotype Grotesque is a family of sans-serif typefaces released by the Monotype Corporation for its hot metal typesetting system. It belongs to the grotesque or industrial genre of early sans-serif designs. Like many early sans-serifs, it forms a sprawling family designed at different times.[1][2]

| |

| Category | Sans-serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Grotesque sans-serif |

| Designer(s) | Frank Hinman Pierpont |

| Foundry | Monotype Corporation |

| Date released | 1926 |

| Re-issuing foundries | Stephenson Blake, Adobe Type, Linotype |

The family was popular in British trade printing, especially its series 215 and 216 regular and bold weights from around 1926, which have been credited to its American-born engineering manager Frank Hinman Pierpont. Several weights have been digitised.

History and design

Monotype Grotesque is a large family of fonts, including very bold, condensed and extended designs, created at different times. Monotype offered a sans-serif capital alphabet as its fourth typeface cut; others were developed later. Like many early sans-serif designs, it is strongly irregular, with designs created at different times that are adapted to suit each width and style at the expense of consistency.[3][4] Monotype executive Dan Rhatigan has commented that it "was never really conceived as a family in the first place, so consistency wasn't a goal."[5]

The inspiration for Monotype Grotesque 215 and 216 has been described as the popular 'Venus' family from the Bauer Type Foundry or 'Ideal', from the H. Berthold AG foundry, which is according to Indra Kupferschmid a Venus clone.[6] Its name descends from William Thorowgood's 1832 face titled "Grotesque."[7][8]

Monotype Grotesque has standard characteristics of the 'industrial' sans-serifs of the period.[9][10] Uppercase characters are of near equal width, the G has a spur in some weights, and the M in the non-condensed weights is square. The 'a' is double-storey. Early fonts have a double-storey 'g' following British tradition and 215 and 216 a single-storey 'g' on the German model.

Monotype Grotesque was somewhat overshadowed from the late 1920s due to the arrival of new sans-serifs such as Kabel, Futura and Gill Sans, also by Monotype. With their cleaner, more constructed and geometric appearance, these designs came to define graphic design of the 1930s, especially in Britain and parts of Europe. (Pierpont was irritated by Monotype advisor Stanley Morison's enthusiasm for marketing Gill Sans, saying that he could "see nothing in this design to recommend it and much that is objectionable."[11]) However, while it never achieved the popularity of Akzidenz Grotesk, it remained a steady seller through the twentieth century. A particular revival of interest took place after the war, and it is often found in avant-garde printing of this period from western and central Europe, such as the journal Typographica designed by Herbert Spencer, since (unlike Akzidenz-Grotesk) it was available from the outset for hot metal machine composition.[7][12][13][14]

Post-war period

With the rise of popularity of neo-grotesque sans-serif typefaces such as Helvetica in the 1950s, which featured a more homogeneous design across a range of styles, Monotype attempted to redesign Monotype Grotesque around 1956 under the name of 'New Grotesque' in a more contemporary style after Pierpont's death in 1937. The project proved abortive (Monotype's obituary of Morison described him as having agreed to it 'without any great enthusiasm'), and did not progress beyond the release of some alternative characters.[15][16][17] Monotype ultimately came to license Univers, Adrian Frutiger's extremely comprehensive new sans-serif family, from Deberny & Peignot.[18] Historian James Mosley has commented that "orders unexpectedly revived" for it around 1960, partly as Univers was only slowly made available on the popular Monotype system, "or maybe they did not want to use the rather bland Univers anyway."[19][8] Mosley wrote in 1999 that the interest in its eccentric design "represents, even more evocatively than Univers, the fresh revolutionary breeze that began to blow through typography in the early sixties," and that "its rather clumsy design seems to have been one of the chief attractions to iconoclastic designers tired of the...prettiness of Gill Sans".[19][8] Phyllis Margaret Handover, a historian and Stanley Morison's assistant, listed some dates for the family in a 1950s article.

Monotype would later use aspects of Monotype Grotesque and New Grotesque as an inspiration for Arial, a new design styled to generally be very similar to Helvetica.[20][21]

Metal type weights

Monotype Grotesque formed a sprawling family with a range of weights sold at different times. The following is a list of known series numbers, their state in post-war specimens and dates where available.[22]

- Regular, series 215 with oblique (1926),[1] single-storey 'g'[23][24]

- Bold, series 216 with oblique (1926),[1] single-storey 'g',[25][26]

- Bold, series 73, different design with a non-strikethrough 'Q'.[27]

- Light, series 126 with oblique, single-storey 'g'.[28][29]

- Medium, series 51 (1910),[1] with the 'g' double-storey. Not digitised in the "Monotype Grotesque" releases.[30][31]

- Condensed, series 33 (1905), a medium weight with a single-storey 'g'. Stephen Coles comments that this series is "really two different typefaces. Note sizes below 14pt are very different than Large Composition and Display Matrices which are essentially Alternate Gothic No. 3. Neither are part of the digital version of Monotype Grotesque."[32][33] Described by Handover as a narrower companion to series 15.[1]

- Condensed, series 318, more condensed than the above, a medium weight with a single-storey 'g'.[34][35]

- Condensed or Extra Condensed, series 383, even more condensed, a medium weight with a single-storey 'g' and no vertical spur on the 'G'.[36][37]

- Bold Condensed, series 15 with oblique (1903),[1] double-storey 'g'.[38] Very similar to "Headline Bold" (below) but different 't' and 'r'.

- Bold Condensed, series 81, double-storey 'g'.[39]

- Bold Extended, series 150 with italic (1921, 1923-4),[1] double-storey 'g', single-storey 'g' and 'a' in italic.[40][41]

- Light Condensed, series 274, single-storey 'g'.[42]

Titling weights (capitals only):

- Condensed Titling, series 523.[43]

- Bold Titling, series 524.[44]

- Bold Condensed Titling, series 527, z-form ampersand, strikethrough 'Q'.[45][46]

- Bold Condensed titling, series 166, more condensed than series 15, z-form ampersand, non-strikethrough 'Q'.[47][22]

Monotype also sold a few other general-purpose sans-serifs, listed here for completeness:

- Headline Bold and Italic, series 595, a clone of Stephenson Blake's popular Grotesque No. 9. Flat-topped 't' and droop on the 'r'.[48]

- Placard, a geometric sans-serif, with weights:

Digital releases

Monotype Grotesque

A release of light and regular styles (with italics), bold and black, light and standard condensed, regular extra-condensed and bold extended weights. This set is also sold by Adobe.

Monotype Grotesque Display

A variant with altered designs. The family consists of Bold Condensed and Bold Extended fonts. Digital version was sold by Linotype.

Classic Grotesque

A less eccentric updating designed by Rod McDonald. The design combines the features in Venus and Ideal Grotesk font families. Alternate characters are also added.[49][50] The development was originally approved in 2008, and lasted four years.[51][52]

The font family originally includes 14 fonts in 7 weights, with a complementary italic. OpenType features include numerators/denominators, fractions, ligatures, lining/old style/proportional and tabular figures, superscript, small capitals, stylistic alternates, stylistic sets 1 and 2 (Roman fonts only). Only one width is offered, without condensed or extended designs.

OpenType Pro version supports all western European, most central European and many eastern European languages.

Condensed, Compressed and Expanded widths were added in 2016, increasing the family to 56 fonts.[53]

References

- Handover, Phyllis Margaret (1958). "Grotesque Letters". Monotype Newsletter, also printed in Motif as "Letters without Serifs".

- Hoefler, Jonathan; Frere-Jones, Tobias. "Knockout". Hoefler & Co. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

The notion of the "type family" is so central to typography that it's easy to forget how recent an invention it is. Throughout most of its history, typography simply evolved the forms that were the most useful and the most interesting, generally with indifference toward how they related to one another. Italic faces existed for decades before they were considered as companions for romans, just as poster types shouted in a range of emphatic tones before they were reimagined as "bold" or "condensed" cousins. The notion that a type family should be planned from the outset is a Modernist concoction, and it's one that type designers have lived with for less than a century…For more than a century before Helvetica, the sans serif landscape was dominated by unrelated designs.

- Coles, Stephen. "Helvetica and alternatives". FontFeed. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Hoefler & Frere-Jones. "Knockout sizes". Hoefler & Frere-Jones.

- Dan Rhatigan [@ultrasparky] (10 December 2013). "@fostertype @Tosche_E @typographica MT Grotesque was never really conceived as a family in the first place, so consistency wasn't a goal" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Shaw, Paul; Kupferschmid, Indra. "Blue Pencil no. 18—Arial addendum no. 3". Paul Shaw Letter Design (blog). Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Ecob, Alexander. "Monotype Grotesque". Eye magazine. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Mosley, James. "The Nymph and the Grot, an update". Type Foundry (blog). Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Gerstner, Karl (1963). "A new basis for the old Akzidenz-Grotesk (English translation)" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Gerstner, Karl (1963). "Die alte Akzidenz-Grotesk auf neuer Basis" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "F.H. Pierpont". MyFonts. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Richard Hollis (2006). Swiss Graphic Design: The Origins and Growth of an International Style, 1920–1965. Laurence King Publishing. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-85669-487-2.

- Grace Lees-Maffei (8 January 2015). Iconic Designs: 50 Stories about 50 Things. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 81–3. ISBN 978-0-85785-353-0.

- Lucienne Roberts (1 November 2005). Drip-dry Shirts: The Evolution of the Graphic Designer. AVA Publishing. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-2-940373-08-6.

- Shaw, Paul. "Arial Addendum no. 3". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Shaw (& Nicholas). "Arial addendum no. 4". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- McDonald, Rob. "Some history about Arial". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- Moran, James (1968). "Stanley Morison" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 43 (3): 28. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Mosley, James (1999). The Nymph and the Grot. London. p. 9.

- Haley, Allan (May–June 2007). "Is Arial Dead Yet?". Step Inside Design. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Type Designer Showcase: Robin Nicholas – Arial". Monotype Imaging. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Monotype Display Faces. London and Salfords: Monotype Corporation. c. 1960–8. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "Grotesque 215". Flickr.

- "Grotesque 215 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold 216". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold 216 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold 73". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Light 126". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Light 126 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque 51". Flickr.

- "Grotesque 51 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed 33". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed 33 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed 318". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed 318 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed 383". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed 383 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold Condensed 15". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold Condensed 81". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold Extended 150". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold Extended 150 (page 2)". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Light Condensed 274". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Condensed Titling 523". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold Titling 524". Flickr.

- "Grotesque Bold Condensed Titling 527". Flickr.

- "A new typographic recipe for The Gourmand". Monotype. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Grotesque Bold Condensed Titling 166". Flickr.

- "Headline MT". MyFonts. Monotype. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- "Introducing Classic Grotesque".

- "Monotype Imaging Announces the Classic Grotesque Typeface Family". PRWeb. 5 September 2012.

- "Classic Grotesque".

- "Classic Grotesque – eine traditionelle Schrift in neuem Gewand – Neue Linotype-Schrift mit umfangreichem Zeichenausbau".

- "Classic Grotesque: three new widths and 42 additional fonts".

Further reading

- Friedl, Frederich, Nicholas Ott and Bernard Stein. Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History. Black Dog & Leventhal: 1998. ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- Jaspert, Berry and Johnson. Encyclopaedia of Type Faces. Cassell Paperback, London; 2001. ISBN 1-84188-139-2

- Macmillan, Neil. An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press: 2006. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

External links

- Monotype Imaging web page for Monotype Grotesque

- Adobe Monotype Grotesque Std: 1, 2

- Monotype Grotesque Font Family – by Monotype Design Studio

- Monotype typefaces

- Monotype System