Morden tube station

Morden is a London Underground station in Morden in the London Borough of Merton. The station is the southern terminus for the Northern line and is the most southerly station on the Underground network. The next station north is South Wimbledon. The station is located on London Road (A24), and is in Travelcard Zone 4. Nearby are Morden Hall Park, the Baitul Futuh Mosque and Morden Park.

| Morden | |

|---|---|

The station entrance | |

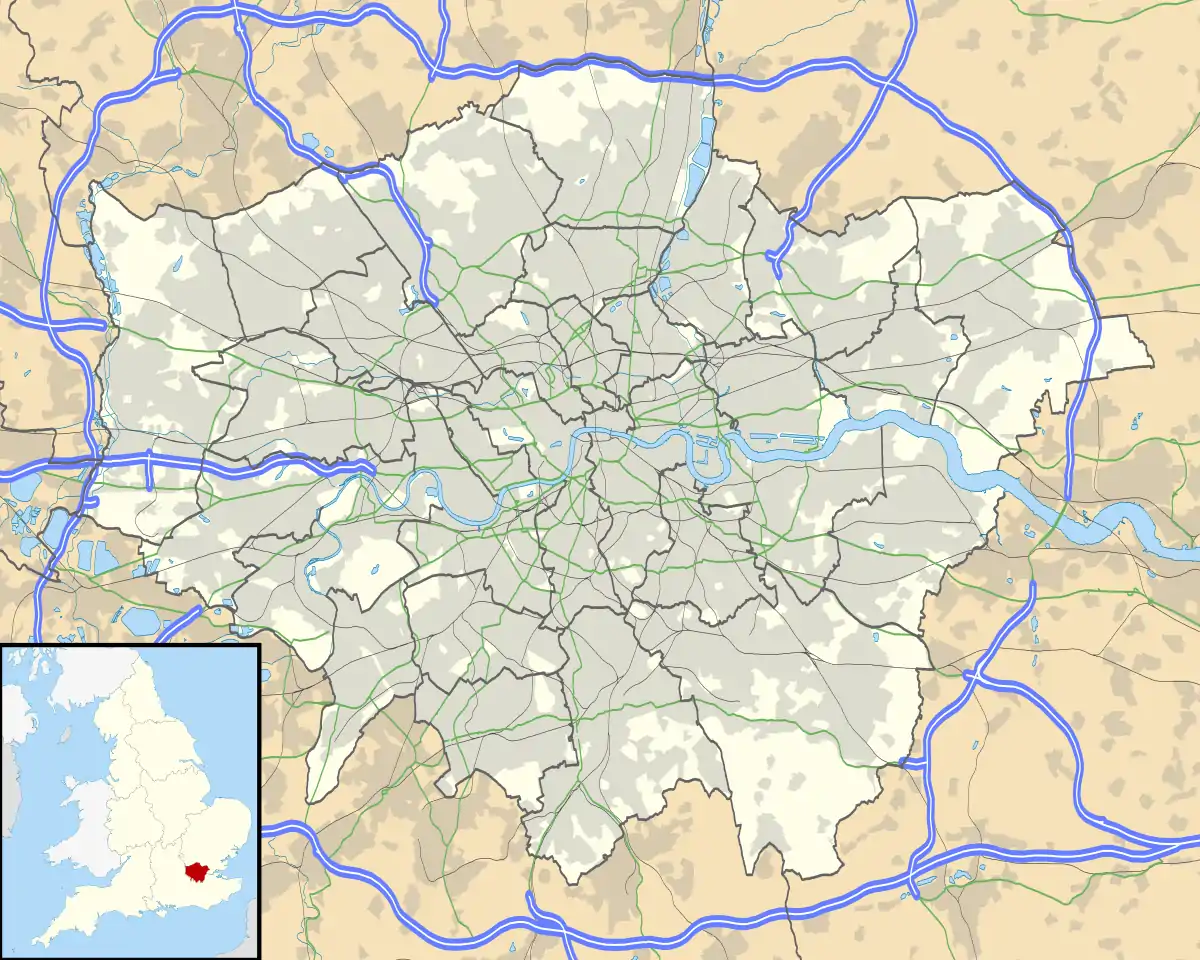

Morden Location of Morden in Greater London | |

| Location | Morden |

| Local authority | Merton |

| Managed by | London Underground |

| Owner | London Underground |

| Number of platforms | 3 |

| Accessible | Yes[1] |

| Fare zone | 4 |

| London Underground annual entry and exit | |

| 2015 | |

| 2016 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2018 | |

| 2019 | |

| Railway companies | |

| Original company | City and South London Railway |

| Key dates | |

| 13 September 1926 | Opened |

| Other information | |

| External links | |

| WGS84 | 51.4022°N 0.1948°W |

The station was one of the first modernist designs produced for the London Underground by Charles Holden. Its opening in 1926 contributed to the rapid development of new suburbs in what was then a rural part of Surrey with the population of the parish increasing nine-fold in the decade 1921–1931.

History

In the period following the end of First World War, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) began reviving a series of prewar plans for line extensions and improvements that had been postponed during the hostilities. Finance for the works was made possible by the government's Trade Facilities Act 1921, which, as a means of alleviating unemployment, provided for the Treasury to underwrite the value of loans raised by companies for public works.[5]

One of the projects that had been postponed was the Wimbledon and Sutton Railway (W&SR), a plan for a new surface line from Wimbledon to Sutton over which the UERL's District Railway had control. The UERL wished to maximise its use of the government's time-limited financial backing,[6] and, in November 1922, presented bills to parliament to construct the W&SR in conjunction with an extension of the UERL's City and South London Railway (C&SLR) south from Clapham Common through Balham, Tooting and Merton.[7][8][9][note 1]

The C&SLR would connect to the W&SR route south of Morden station and run trains to Sutton and the District Railway would run trains between Wimbledon and Sutton.[11] Under these proposals, the station on the C&SLR extension would have been named "North Morden" and the station on the W&SR route would have been called "South Morden" (the current Morden South station is in a different location).[12][13] The proposals also included a depot at Morden for use by both District Railway and C&SLR trains.[11]

The Southern Railway objected to this encroachment into its area of operation and the anticipated loss of its passenger traffic to the C&SLR's more direct route to central London. The UERL and SR reached an agreement in July 1923 that enabled the C&SLR to extend as far as Morden in exchange for the UERL giving up its rights over the W&SR route.[11][note 2] Construction of the C&SLR extension was rapidly carried out and Morden station was opened on 13 September 1926.[15]

Once the station was opened, the UERL established Morden station, the southernmost on the system, as the hub for numerous bus routes heading further into suburban south London and northern Surrey. These routes had a significant impact on the Southern Railway's main line operations in the area, with the SR estimating in 1928 that it had lost approximately four million passengers per year.[11][16] The UERL though was able to demonstrate that its passenger numbers on its buses to Sutton station were actually more than double those for Morden.[16] Across the road from the station, the UERL opened its own petrol station (the first of its kind in the country) and garage where commuters with cars, or bicycles, could leave their vehicles during the day.[17][18][19][note 3] The opening of the C&SLR and the Wimbledon to Sutton line led to rapid construction of suburban housing throughout the area. The population of the parish of Morden, previously the most rural of the areas through which the lines passed, increased from 1,355 in 1921 to 12,618 in 1931 and 35,417 in 1951.[20]

A post-war review of rail transport in the London area produced a report in 1946 that proposed many new lines and identified the Morden branch as being the most overcrowded section of the London Underground, needing additional capacity.[21] To relieve the congestion and to provide a new service south of Morden, the report recommended construction of a second pair of tunnels beneath the northern line's tunnels from Tooting Broadway to Kennington and an extension from Morden to North Cheam.[22][note 4] Trains using the existing tunnels would start and end at Tooting Broadway with the service in the new tunnels joining the existing tunnels to Morden. The extension to North Cheam would run in tunnel.[22] Designated as routes 10 and 11, these proposals were not developed by the London Passenger Transport Board or its successor organisations.[note 5]

Station building

.jpg.webp)

Morden in 1926 was a rural area and the station was built on open farmland, giving its architect, Charles Holden, more space than had been available for the majority of the stations on the new extension which were located in already built-up areas. The stations on the Morden extension were Holden's first major project for the Underground.[25] He was selected by Frank Pick, general manager of the UERL, to design the stations after he was dissatisfied with designs produced by the UERL's own architect, Stanley Heaps.[26]

In a letter to his friend Harry Peach, a fellow member of the Design and Industries Association (DIA), Pick explained his choice of Holden: "I may say that we are going to build our stations upon the Morden extension railway to the most modern pattern. We are going to discard entirely all ornament. We are going to build in reinforced concrete. The station will be simply a hole in the wall, everything being sacrificed to the doorway and some notice above to tell you to what the doorway leads. We are going to represent the DIA gone mad, and in order that I may go mad in good company I have got Holden to see that we do it properly."[27][note 6]

Built with a range of shops to both sides, the modernist design of the entrance vestibule takes the form of a double-height box clad in white Portland stone with a three-part glazed screen on the front façade divided by columns of which the capitals are three-dimensional versions of the Underground roundel. The central panel of the screen contains a large version of the roundel. The ticket hall beyond is octagonal with a central roof light of the same shape. The ticket hall originally had a pair of wooden ticket booths (passimeters) from which tickets were issued and collected,[29] but these were removed when modern ticketing systems made them redundant.

The main structure of the station and the shops to each side was designed with the intention of taking upward development on its roof, though this did not come until around 1960 when three storeys of office building were added.[30]

Unlike the other stations built for the extension, the station's platforms are not in tunnels, but in a wide cutting with the tunnel portals a short distance to the north.[note 7] Three tracks run through the station to the depot, and the station has three platforms, two of which are island platforms with tracks on each side. The platforms are accessed by steps down from the ticket hall and are numbered 1 to 5 from east to west; the island platforms have different numbers for each face (2/3 and 4/5). To indicate departures, the platforms are usually referred to as 2, 3 and 5.[32] The tunnel portals are one end of the longest tunnel on the London Underground running 27.8 kilometres (17.3 mi) to East Finchley via the Bank branch.[33][note 8]

Refurbishment and improvement works completed in 2007 included new and reconstructed cross bridges between platforms and the installation of lifts for mobility impaired passengers.[35] Cosmetic improvements carried out at the same time included the reinstatement of pole-mounted roundels on the sides of the entrance vestibule.[note 9] Other work in the 2000s at the station includes the construction of a substantial air rights building spanning across the cutting.[36]

The station is locally listed by Merton Council as being of architectural interest,[37] though not statutorily listed like the others on the Morden extension.[note 10]

Services and connections

The station sits at the southern end of the Northern line in London fare zone 4.[40] It is the southernmost station on the whole London Underground network.[40][note 11] The next station to the north is South Wimbledon.[40] Train frequencies vary throughout the day, but generally operate every 2–5 minutes between 05:15 and 00:05.[41]

London Bus routes 80, 93, 118, 154, 157, 163, 164, 201, 293, 413, 470 and K5, and night routes N133 and N155 serve the station.[42]

Future

If built, a planned extension to the Tramlink light rail system would create a new tram interchange close to Morden, offering tram services to Sutton via St Helier.[43]

Notes and references

Notes

- The C&SLR extension was to be "6 miles, 1 furlong and 7.2 chains" (6.215 miles or 10.00 kilometres) long and mostly in tunnel.[9] Originally opened in 1890, the C&SLR's original tunnels were smaller than the standard diameter used on the Underground's later deep-level lines and the C&SLR was already undergoing reconstruction to enlarge its tunnels to take larger, modern rolling stock.[10]

- The Southern Railway subsequently built the W&SR line, one of the last main line routes to be built in the London area. The first section from Wimbledon to South Merton opened on 7 July 1929, with the line being opened in full on 5 January 1930.[14]

- The garage was located next to the railway cutting to Morden depot on part of the land now occupied by an Iceland supermarket.

- A duplication of parts of the Northern line's tunnels had first been considered in 1935 when new tunnels were proposed between Camden Town and Waterloo and between Balham and Kennington.[23] During the war, deep-level shelters were constructed beneath a number of Northern line stations so that they could be converted for use as part of the duplicate tunnels after the war.[24]

- Of the twelve proposed routes, only Route 8, "A South to North Link - East Croydon to Finsbury Park" was developed, eventually becoming the Victoria line.

- As part of the design process, a full-size mock-up of the entrance to one of the stations on the extension was erected in an exhibition hall.[28]

- The section of tunnel immediately north of the portal was constructed as a cut and cover tunnel. The original intention was to leave it as an open cutting, but the wet condition of the ground made it necessary to cover the tunnel. The cut and cover section is covered by a small linear park, Kendor Gardens, north of which the tracks separate into standard tube tunnels. A total of 82,000 cubic yards (63,000 m3) of spoil excavated from the station cutting, the cut and cover section of tunnel and part of the tube tunnel towards South Wimbledon was removed using an aerial ropeway for disposal in a gravel pit about half a mile away.[31]

- When the Northern line tunnels were extended from Archway to East Finchley in 1939, the tunnel was the longest in the world.[34]

- Pole-mounted roundels were used on all of the stations on the Morden extension, but were gradually lost during modernisations. Photographs indicate that they were removed from Morden station in the mid-1950s and replaced with large, flat roundels.

- Clapham South, Balham, Tooting Bec, Tooting Broadway, Colliers Wood and South Wimbledon stations are all Grade II listed.[38][39]

- Though tube maps also show West Croydon station, which is geographically further south than Morden, that station is part of the London Overground network.

References

- "Step free Tube Guide" (PDF). Transport for London. May 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020.

- "Multi-year station entry-and-exit figures (2007–2017)" (XLSX). London Underground station passenger usage data. Transport for London. January 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Station Usage Data" (CSV). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2018. Transport for London. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2019. Transport for London. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 90.

- Barman 1979, pp. 78–79.

- "No. 32769". The London Gazette. 21 November 1922. pp. 8233–8234.

- "No. 32769". The London Gazette. 21 November 1922. pp. 8230–8233.

- "No. 32770". The London Gazette. 24 November 1922. pp. 8314–8315.

- Day & Reed 2010, pp. 90–1.

- Jackson 1966, p. 678.

- Harris 2006, p. 49.

- "Diagram of new works in hand". London Transport Museum. 1922. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Jackson 1966, p. 679.

- Rose 1999.

- Barman 1979, p. 68.

- Emmerson, Andrew. (2010). The London underground. Oxford: Shire. ISBN 978-0-7478-0790-2. OCLC 462882243.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 97.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 225–6.

- 1921 and 1931 data – 1931 Census: England and Wales: Series of County Parts, Part I. County of Surrey, Table 3. 1951 data – 1951 Census: England and Wales: County Report: Surrey, Table 3.

- Inglis 1946, p. 16.

- Inglis 1946, p. 17.

- Emmerson & Beard 2004, p. 16.

- Emmerson & Beard 2004, pp. 30–37.

- Martin 2013, p. 186.

- Orsini 2010.

- Pick (1925), letter to Harry Peach, quoted in Barman 1979, p. 118.

- "Mock-up". London Transport Museum. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Badsey-Ellis 2012, p. 113.

- Morden Station Planning Brief 2014, p. 16.

- Badsey-Ellis 2016, pp. 191–92.

- "Morden Underground Station". Transport for London. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- "Facts & Figures". Transport for London. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 134.

- "Station Refurbishment Summary: July" (PDF). London Underground Railway Society. July 2007. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Williams, David (July 2007). "Regeneration" (PDF). Merton London Borough Council. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- "Locally listed buildings in Merton". London Borough of Merton. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "Listed buildings and borough history". Wandsworth London Borough Council. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Listed Buildings: A Guide for Owners (PDF) (Report). Merton London Borough Council. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Standard Tube Map (PDF) (Map). Not to scale. Transport for London. May 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "Northern line timetable: From Morden Underground station". Transport for London. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Buses from Morden" (PDF). Transport for London. 12 September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- White, Anna (26 September 2017). "Exclusive: Tramlink extension set to bring 10,000 new homes to south-west London as TfL promises £70m to project". Evening Standard. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

Bibliography

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2012). Underground Heritage. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-360-0.

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2016). Building London's Underground: From Cut-and Cover to Crossrail. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-8541-4397-6.

- Barman, Christian (1979). The Man Who Built London Transport: A Biography of Frank Pick. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7753-1.

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2010) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-341-9.

- Emmerson, Andrew; Beard, Tony (2004). London's Secret Tubes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-283-6.

- Harris, Cyril M. (2006) [1977]. What's in a Name?. Capital History. ISBN 1-85414-241-0.

- Inglis, Charles (21 January 1946). Report to the Minister of War Transport. Ministry of War Transport/His Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Jackson, Alan A. (December 1966). "The Wimbledon & Sutton Railway: A late arrival on the South London suburban scene" (PDF). The Railway Magazine: 675–680. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "Morden Station Planning Brief" (PDF). London Borough of Merton. March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Martin, Andrew (2013) [2012]. Underground Overground. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84668-478-4.

- Orsini, Fiona (2010). Underground Journeys: Charles Holden's designs for London Transport (PDF). V&A + RIBA Architecture Partnership. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Rose, Douglas (1999) [1980]. The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History. Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-219-4.

- Wolmar, Christian (2005) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.

External links

Media related to Morden tube station at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Morden tube station at Wikimedia Commons- Historic photographs of the station:

- Historic film of the station:

- "World's Longest Tube – London's new traffic artery opened by Lt. Col Moore Brabazon". British Pathe. 1926. Retrieved 2 November 2014. Silent newsreel footage of Lt-Col. John Moore-Brabazon junior Transport Minister opening the Morden extension.

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminus | Northern line |