Morley Baer

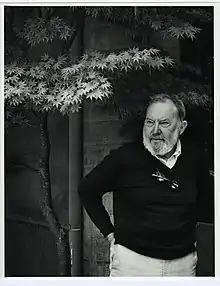

Morley Baer (April 5, 1916 – November 9, 1995), an American photographer and teacher, was born in Toledo, Ohio. Baer was head of the photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute, and known for his photographs of San Francisco's "Painted Ladies" Victorian houses, California buildings, landscape and seascapes.[1]

Morley Baer | |

|---|---|

Morley Baer, Monterey, CA, Aug 1987, Provided by Bill Baxter | |

| Born | April 5, 1916 |

| Died | November 9, 1995 |

| Education | University of Toledo, 1934; B.A, M.A University of Michigan, 1938 |

| Known for | Architectural Photographer; Instructor San Francisco Art Institute; Instructor, UC Santa Cruz |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Baer (née Manney), a visual artist |

| Awards | American Institute of Architects Architectural Photography Award, 1966; Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, 1980 |

Baer learned basic commercial photography in Chicago and honed his skills as a World War II United States Navy combat photographer. Returning to civilian life, over the next few years he developed into "one of the foremost architectural photographers in the world,"[2] receiving important commissions from premier architects in post-war Central California. In the early 1970s, influenced by a friendship with Edward Weston, Baer began to concentrate on his personal landscape art photography. During the last decades of the 20th century, he also became a sought-after instructor in various colleges and workshops teaching the art of landscape photography.

Early life and education

Morley Baer's parents encouraged him in an active outdoor life growing up in Toledo. He attended the University of Toledo in 1934 and later transferred to the University of Michigan from where he graduated in 1937 with a BA in English. Continuing on there, he earned an MA in Theater Arts in 1938. Baer soon found a dull but well-paying job in the advertising office of the Chicago department store Marshall Field's. Dissatisfied, he apprenticed as a low-paid menial assistant, at a greatly reduced salary, to a Michigan Avenue commercial photography company. He shortly was photographing in the field, and developing and printing photographs.[3]

Along with two associates, Baer was sent on assignment to Colorado in 1939. He had seen an exhibition of Edward Weston's photographs at the Katherine Kuh Galleries in January of that year, and became enamored at the sparse elegance of Weston's black-and-white prints. He extended his trip west to California to meet Weston at his studio in Carmel-by-the-Sea. The two did not meet, but Baer made the most of the trip by visiting San Francisco, the Monterey Peninsula, and Carmel.

Military photographer

Although he returned to Chicago, he already had applied for Art Center School while in San Francisco but his plans were derailed by the onset of World War II. In 1941 he enlisted in the Navy almost immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor and went through the Navy photo school at Pensacola, where he learned to adjust to its stereotyped approach to producing photographs. Baer graduated, commissioned as an ensign, and was transferred to Norfolk for a series of stories on the Atlantic Theater of operations.[3]

His duties included public relations, aircraft recon, editorial assignments, teaching, and combat photography from aircraft and carriers. Accompanied by a writer, Baer covered military operations in North Africa, southern France, Brazil, and the Caribbean Sea. In 1945 he was assigned to the operational Naval Aviation Photographic Unit, commanded by the photographer Edward Steichen. Working under a variety of terrain, sea, and weather conditions, ever changing light, and new environments in physically demanding activities, he made dozens of photographs a day, and perfected his technical and compositional photographic skills. When discharged from the Navy in 1946 he was a complete and confident professional photographer.[3][4]

Post-war years

In 1945 Baer, now a civilian in San Francisco, met up again with Frances Manney, a young woman awaiting admission to Stanford University, who previously had hired Baer as her photography tutor during his brief time in Norfolk.[2] The two married and investing their dwindling funds, established a commercial photography business in a small store-front studio in Carmel in 1946.[3]

Baer had no difficulty discovering opportunities aplenty in the booming post-war building trades. In dire need of competent photographers to illustrate their projects, builders and architects vied to hire the Baer team. As his reputation grew, he had as much work as he could handle. His published architectural photographs from that time testify to his active professional career. His clients were among the more noted Bay Area architectural firms.[5][6]

Although Baer had briefly fulfilled his long-held dream of meeting Edward Weston, they had met only briefly. So, through a Weston friend sometime in 1947, Baer learned of an Ansco view camera for sale, a camera he had previously used in Chicago and was very familiar with its capabilities. Able to buy it for the then princely sum of $90,[2] it became the camera he most used for the rest of his life. Although he had others for some assignments, the Ansco was the instrument with which he made his most memorable photographs. It became almost an extension of his photographic seeing and visualization in his later fine art landscape work.[7]

Morley and Frances became frequent visitors to Edward Weston's home/studio in Carmel's Wildcat Hill and with whom they had a close friendship until Weston's death in 1958. For the production of Weston's monumental photographic Portfolios I and II Morley worked closely with Edward's son Brett Weston in making the prints, while Frances did the spotting of the finished prints. Besides being helpful to Weston, this association greatly benefited Baer's career in the world of fine-art photography. Through Weston he met most of the prominent West Coast photographers. The more noted among them earlier had formed Group f/64 in San Francisco; its members included Weston, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke, and Henry Swift, among others.

Baer again met up with Steichen in 1950 when he and Frances made a trip to New York. Although Steichen carefully examined the photographic portfolio Baer showed him, he was less than enthralled by its subject matter – their photographic sensitivities were vastly different.[4][8]

Bay Area residency

Finding attractive work opportunities in the San Francisco area in the early fifties, the Baers sold their house on Carmelo Avenue in Carmel and re-located to Berkeley. Baer soon was making a name for himself as a leading architectural photographer performing portfolio work for architects and interior designers while freelancing for housing design magazines.[4] Ansel Adams recruited him as an instructor at the San Francisco Art Institute, then under the direction of Minor White. When White left for the East Coast in 1953, Baer became Head of the Institute's Photography Department.

In 1953 the Baers moved into a 1920s era house in Greenwood Common that had been renovated by architect Rudolph Schindler for its owner, who sold it in 1951 to William Wurster, who, in turn, sold it in 1953 to Baer.[9] Baer soon became very active in neighborhood affairs. Showing their lifetime appreciation for landscaping, the Baers hired Lawrence Halprin to design their outdoor areas.

Baer rapidly became a sought-after architectural photographer for noted architects, including Craig Edwards, the firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM), Charles Willard Moore, and William Turnbull, Jr..[10] Baer's photographs of buildings by Bernard Maybeck, Greene and Greene, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Julia Morgan are considered important today in understanding American architecture and design in the first half of the 20th century.

1960s onwards

Through the influence of Nathaniel A. Owings, SOM hired Baer to photograph US consulate buildings being constructed throughout Western Europe. The Baers and their young son moved to Spain for two years. Baer found time to produce personal work by photographing out-of-the-way locations in Andalucia. The family traveled the country in a VW bus in which they camped as necessary, freeing them to go where they pleased. These photographs led to Baer's first one-man exhibition at San Francisco's M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in 1959 and his first published portfolio.[3]

When he returned to California, SOM hired Baer for a large photographic survey that lasted through the mid-1960s. During this time Baer also was the architectural photographer for the pioneering Sea Ranch, California in Gualala. He contributed work for the 1965 Sierra Club publication Not Man Apart, which also included entries from artists such as Robinson Jeffers, Dorothea Lange, and Beaumont Newhall.[11] Jeffers exerted a strong influence on Baer's subsequent thinking and artistic sensitivities.[12]In fact, Baer was so impressed by Jeffers that he began forming the idea of combining his photographs of the Sur coastline with Jeffers' somber but expansive poetry. Finally getting around to this project in his last years, it resulted in the book "Stones of the Sur", brilliantly curated by James Karman. The dynamic juxtaposition of photographs and poetry combined to reveal, in a mild paraphrasing of Karman, "much about the meaning and mystery of the world".

In 1966 the American Institute of Architects gave Baer their Architectural Photography Award.

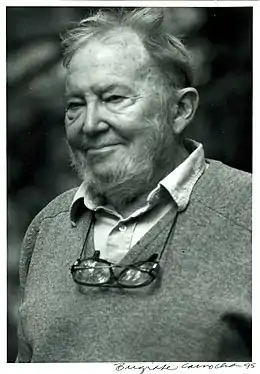

by Brigitte Carnochan

The success of Not Man Apart led to a later assignment as the principal photographer for the 1968 publication, Here Today. Subsequently he was selected as the only photographer for the 1978 book Painted Ladies, a collection of color photographs of the more stately San Francisco Victorian houses, Baer's first major color photography project.[13]

Garrapata

In 1965 the Baers built a second home and studio, designed by Bay Area Modernist architect William Wurster, south of Carmel near the Big Sur coast with dramatic shore and ocean views. Wurster designed the two-story house with its river-stone facade, creating an organic building blending with the surrounding rocks and cliffs, and sometimes referred to as 'The Stone House.'[2] It commanded a striking view of Garrapata Beach and Soberanes Point with its long stretches of surf and beach. Unfortunately, Frances never felt comfortable in the Stone House, feeling it cold, damp, and isolated and continued to live in Berkeley while Morley used the Garrapata residence as his combination home and studio. The remote coastal location brought Baer into intimate contact with the primal natural elements of wind, water, light, and rocks at the cliffs and beach, an environment in which he did much of his best work.

However his photographic eye seldom left architecture. He recounts standing on a sidewalk in downtown Monterey waiting for his equipment to dry after a heavy rainstorm, when he began studying the surrounding classic Monterey buildings. Becoming increasingly interested in their clean lines, he resolved to photograph them. This began his late 60s/early 70s Monterey Historical Series which resulted in his book 'Adobes in the Sun'.[14]

With Garrapata as his base, Baer photographed throughout the West but mostly in Central California. He exhibited his landscape portfolios of classical black-and-white photographs, wrote or contributed to several books of photography, and became an instructor in photography workshops. In the early 1970s, Baer joined Adams and other prominent central California fine art photographers to found the Friends of Photography in Carmel,[8] which organized yearly photographic student workshops at Carmel's Sunset Center and at the Julia Morgan-designed Asilomar Conference Grounds. Those workshops inspired development of what became known as the West Coast style of landscape photography through the last decades of the 20th Century.[15] He published two photography collections in 1973, 'Andalucia' and 'Garrapata Rock'.

Along with his increasing success as a fine art landscape photographer, Baer continued with assignments as a commercial architectural photographer for several architect clients primarily throughout the Monterey Peninsula. He was the sole photographer for the exhibition, California Design 1910[6] in late 1974 at the Pasadena Conference Center; one of his landscape photographs graces the cover.

Recalling his grandfather's accounts of his yearly journeys from Ohio to California, Morley was enamored by visions of California's golden hills and sea-swept coasts. So, when he read the poetic descriptions of the western lands by the early 20th writer, Mary Austin, he conceived the idea of matching some particularly lucid passages from her book, The Land of Little Rain, with some of his more appropriate photographs. Result was the 1979 book, Room and Time Enough.[16] He teamed with Augusta Fink, the biographer of Mary Austin, to produce a synergistic combination of prose and photography into a paean to the Western landscape.

Carmel

In 1972, after the couple became temporarily estranged, the Baers sold the Greenwood Common house. Frances remained as an art teacher in the Bay Area. In 1979 they sold the Garrapata house, and Morley briefly moved to a smaller home in Carmel. In 1980, Baer was awarded the Rome Prize in Design and a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, where he mainly photographed the fountains of Rome. Baer had an exhibition, appropriately titled "The Fountains of Rome", in May 1981 at the Bonnafont Gallery in San Francisco.[3] He returned to his Carmel home/studio after the year in Rome, and reunited with Frances. The couple then bought a house/studio on Carmel Valley Road in 1985, where they lived the remainder of their lives.

Photographic philosophies and techniques

From the beginning of their relationship, both as husband and wife and as business partners, Morley and Frances Baer worked as a team. Their separate but personal photographic visions and techniques centered around careful composition of the subject matter, complete familiarity with their equipment and materials, and dedication to the art and profession of photography. Both believed that only the view camera – Morley with an 8x10, Frances with a 5x7 – allowed them to express their feelings about a photographic subject.[17] Although devoted partners, the Baers were intense mutual competitors and had an arrangement for 'artistic rights' to a potential photograph discovered while driving the countryside – as Frances recounts in her chapter, "Rules of the Road" in 'California Plain'. It belonged to the person on whose side of the car the subject lay.

Whenever we are driving, subject matter on the left side of the road is the domain of the driver, and the passenger has first dibs on everything on the right side.[7]:101

Baer's overall approach to making a photograph was centered on uniting technical capabilities of his camera and lens with emotional feelings at the moment of making the photograph. He always would apply his 'strongest seeing,' to borrow a phrase from Edward Weston,[18] to bring out what he saw as the dominant element in a scene. His photographs were always finely set up, some would say "tightly". Although he eschewed use of the term 'composition', he applied an admonition from Weston that "composition is just the strongest way of seeing". Indeed, along with that uncompromising admonishment, Morley held to an amplifying Weston dictum that "Photography as a creative expression ... must be seeing plus". Dr Jim Jordan[19] may have captured Baer's philosophy expressed by his photographs in his essay on Morley in his book (p 15 of the 'Light Years' essay), in that Baer finds universal themes in his subjects precisely because he has searched inwardly to relate to them on an intense visceral level, "The photograph itself is a kind of icon, an object in its own right that acts upon the emotional and intellectual relationship between the photographer and subject ..."

Morley Baer's philosophy of art photography, and indeed of life itself, is exemplified in the work of several of his photographic assistants. Among them are Marco Zecchin,[20] Patrick Jablonski,[21] Frank Long, and the late Erik Lauritzen.[22] Lauritzen's own work is archived at UC Santa Cruz.

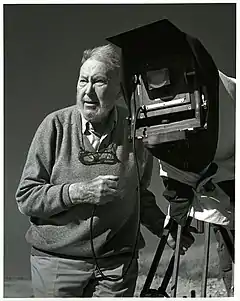

Equipment

Motivated by a strong sense of simplicity in equipment and technique learned from Edward Weston, and reinforced by his readings of Robinson Jeffers' sparse poetry for which he had sincere admiration,[4] Baer reduced his photographic equipment to a compact minimum.[12] With time and experience, he acquired the equipment and techniques that completely suited his photographic style. Once he had settled on a particular technique he rarely changed it. Baer used the same Ansco 8x10S view camera on an apparently flimsy but really very sturdy wood tripod for virtually all his serious photography.[2] After fifty years of usage the Ansco had become almost an extension of his mind and eye; he could adjust its settings by feel alone while under his darkcloth and concentrating on his subject in the ground glass viewer. Eloquently, almost lovingly, he expresses his feelings towards the ancient Ansco in his Photographers Notes in The Wilder Shore.

Baer designed a special metal carrying case, with a sturdy leather-strap handle, constructed for him by a Monterey metal worker. He replaced it only once during his career. The case held his camera, several lenses, film holders and other paraphernalia he needed in the field.[13] With his camera on one shoulder, and the carrying case in the opposite hand, he was perfectly laterally balanced as he strode towards the subject of his photograph.

Precise in his lens selection and use, Baer used a wide range of lens focal lengths from a 120 mm wide angle to a 19" (480 mm), what he called his 'long lens'.[10] As his favorite lens he claimed that "It sees how I see the material." [7] Having a lens for almost every occasion was important since Baer did mostly contact prints of his 8x10 negatives where, besides being esthetically displeasing to him, cropping was not an option. Although owning a Navy surplus Saltzman 8x10 enlarger,[23] he rarely used it since contact prints were his preferred medium of expression – it's now a prized possession of one of his last assistants. He standardized his procedures to the extent possible, based on thorough testing for film exposure and development characteristics, changing them only when necessary.

Darkroom techniques

Baer developed his 8x10 negatives by inspection during the development process. While the development was well underway, he would briefly check his highlight densities with a dim green safelight and continued development until he obtained his desired densities.[7] He developed early Isopan and later Super XX Black & White film in his variation of ABC Pyro. Although reluctant to use filters, Baer did so when necessary for effectively expressing the subject – as he described in technical entries in his several books. He seldom changed from his favorite film (Pyro) and print developers (Amidol),[24] modifying them as materials evolved.[25]

Baer's explains his techniques for achieving the vivid colors of the subjects in Painted Ladies in a short article (P79). He decided that 'Eastman's Professional Ektachrome as the most amenable color material (this was late 70s). He had it processed by a professional laboratory and achieved the consistent fine results he sought.

In his Photographer's Notes to The Wilder Shore (p151) he explains what he was trying to express in his photographs of the California landscape and his frequent use of color to achieve it. He continued with Professional Ektachrome film developed in a commercial developer but exposed at values he worked out in extensive testing to achieve the subdued colors he thought best expressed subtleties of the California landscape.

With his varied Navy photography experience, his many years of study, and intimate knowledge of his equipment, materials and darkroom techniques, Baer was well-qualified to take on any photographic assignment that came along. That confidence also allowed him to concentrate on the photographic task at hand, "... to interpret and thus to fully realize the potential for maximum expression ..." in his photographs.[2] In evaluating a potential photographic subject, Baer thought both in esthetic and organizational terms but also in the technical challenges he would face in actually making the photograph. His assistant once watched Baer as he stared at a subject tree muttering, 'I am looking at the Pyro in the tree trunks [for the negative] and the Amidol [for the print] in the leaves'.[7] He already was thinking of the technical problems he would have to solve in exposing the negative to get the tones he wanted in the final print.

Legacy

Morley Baer died in 1995, in Monterey, California. His photographic archive was divided between personal work and architectural work. Film negatives that Baer felt represented his most significant work were given to the Special Collections of the University of California, Santa Cruz.[3] His architecture photography archive, comprising mostly photographs of Stanford University buildings commissioned by the University or its architects, are housed at Stanford University.[26] All his other archives, containing numerous entries, are itemized in the Online Archive of California.[27]

A final tribute to Baer's artistry and emotional sensitivity may be abstracted from James Karman's assessment of the feelings of both Morley Baer and Robinson Jeffers toward the earth in general, and towards the Big Sur coast in particular. In his insightful and scholarly Introduction in "Stones of the Sur", he captures the magnetic attraction of the magnificent wild coastline for both Jeffers and Baer.

Baer shared the same sense of mystery — and the feeling of tenderness for the mote that we inhabit, with its massive mountains and fathomless seas. Like Jeffers, living on the edge of the continent, he was attuned to an order and a scale of existence beyond the human; he sought to document the sublime beauty, alien and austere at times, of the natural world, especially that portion ... he encountered in his beloved Big Sur.[4]:p 20

Karman also touched on Baer's love of teaching.[28] In addition to the formal institutions, in late Fall 1985, Baer created his own Annual Master Photographers Invitational Photographic workshops. He mailed invitations to selected students, scouted the venues, organized accommodations, and selected his preferred restaurants. He and his photographic assistant eagerly participated with the students, with Baer speculating on how he was viewing his subject and how he'd eventually create a printable negative. Afterwards, he hosted workshop students in his Carmel Valley home for his legendary English bangers BBQ. Afterwards, he leafed through his current portfolio, commenting on it and answering students' questions. Frances, hovering in the background, sometimes joined the group, obviously enjoying the sessions.

References

- Adams, Ansel (1985). Ansel Adams, an Autobiography. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-1596-5.

- Adams, Ansel (1980). The Camera. Boston: New York Graphic Society. ISBN 0-8212-1092-0.

- Adams, Ansel (1995). The Negative. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-8212-2186-0.

- Adams, Ansel (1985). The Print. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-8212-2187-7.

- Andersen, Timothy; Moore, Eudorah M.; Winder, Robert W. (1980). California Design 1910. Baer, Morley (photographer). Santa Barbara, CA: Peregrine Smith. ISBN 0-87905-055-1.

- Baer, Morley; Fink, Augusta (1972). Adobes in the Sun. Chronicle Books San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-87701-193-4.

- Baer, Morley (2002). California Plain: Remembering Barns. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4270-7. [29]

- Baer, Morley; Wallace, David Rains (1984). The Wilder Shore. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0-87156-328-2.

- Baer, Morley (1988). Light Years: The Photographs of Morley Baer. Carmel, CA: Photography West Graphics. ISBN 0-9616515-2-0., Text by Dr. Jim Jordan

- Baer, Morley (1979). Room and Time Enough: The Land of Mary Austin. Flagstaff, AZ: Northland Press. ISBN 0-87358-205-5.

- Conger, Amy (1981). The Monterey Photographic Tradition: The Weston Years. Monterey, CA: Monterey Peninsula Museum of Art., Essay by Amy Conger, PhD

- Jeffers, Robinson (1969). Brower, David Ross (ed.). Not Man Apart: Photographs of the Big Sur. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 978-0-88486-005-1.

- Karman, James (2002). Stones of the Sur: Poetry by Robinson Jeffers, Photographs by Morley Baer. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3942-0.

- Lowell, Waverly B. (2009). Living Modern: A Biography of Greenwood Common. San Francisco: William Stout Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9795508-6-7.

- Olmstead, Roger; Watkins, T. W.; Baer, Morley (1978). The Junior League of San Francisco (ed.). Here Today: San Francisco's Architectural Heritage. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-87701-125-7.

- Pomada, Elizabeth; Larsen, Michael; Baer, Morley (1978). Painted Ladies: San Francisco's Resplendent Victorians. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-47523-0.

- Seavey, Kent (2007). Carmel: A History in Architecture. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4705-3.

- Weston, Edward (1991). Newhall, Nancy (ed.). The Daybooks of Edward Weston. New York: Aperture. ISBN 978-0-89381-450-2.

Notes

- Obituary at SF Gate, November 11, 1995

- Baer, 1988

- [https://oac.cdlib.org/search?style=oac4&ff=0&institution=UC+Santa+Cruz&query=Morley+Baer&x=15&y=7

- Karman, James, 2002

- Olmstead, 1968

- Andersen, 1980

- Baer, 2002

- Adams, 1985

- Lowell, 2009

- Fink, 1980

- Jeffers, 1965

- Olmstead, 1968

- Pomada, 1978

- Baer, 1972

- Conger, Amy, 1981

- Baer, Morley, 1979

- Adams, 1980

- Weston, 1991

- http://www.antiochcollege.edu/news/obituaries/james-jim-william-jordan-former-faculty

- http://marcozecchin.com

- http://www.patrickjablonski.com

- http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt796nc97p/

- John Sexton Tribute; Apogee Photo Magazine, late 1995

- Adams, 1995

- Baer, Morley, 1979

- Morley Baer photographs, 1954–1977

- https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6q2nf55x/

- Karman, James (2002), p 7

- "California Plain: Remembering Barns" — Stanford University Press webpage; reviews and orders.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morley Baer. |

- Morley Baer Photographs and Archives(Stanford University Archives)

- Morley Baer Photographs and Archives(UCSC)

- UC Santa Cruz photography archives

- Photography West Gallery: Morley Baer — Baer images by topic.

- SFGate.com: Obituary

Media related to Morley Baer at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Morley Baer at Wikimedia Commons- Marco Zecchin Photography

- Erik Lauritzen Photographs (Stanford University Archives)

- Patrick Jablonski Photography

[[Category:People from Carmel-by-the-Sea, California]