Mortise lock

A mortise lock (also spelled mortice lock in British English) is a lock that requires a pocket—the mortise—to be cut into the edge of the door or piece of furniture into which the lock is to be fitted. In most parts of the world, mortise locks are found on older buildings constructed before the advent of bored cylindrical locks, but they have recently become more common in commercial and upmarket residential construction in the United States. They are widely used in domestic properties of all ages in Europe.

History in the United States

Mortise locks have been used as part of door hardware systems in America since the second quarter of the eighteenth century. In these early forms, the mortise lock mechanism was combined with a pull to open the unlocked door. Eventually, pulls were replaced by knobs.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, mortise locks were only used in the most formal rooms in the most expensive houses. Other rooms used box locks, or rim locks, in which, unlike in mortise locks, the latch itself is in a self-contained unit that is applied to the outside of the door. Rim locks have been used in the United States since the early eighteenth century.[1] A rim lock has the lock body and bolt mechanism on the outside of the door, unlike a mortise lock, where the bolt is inside the door.

An early example of the use of mortise locks in conjunction with rim locks in one house comes from Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. In 1805, Jefferson wrote to his joiner listing the locks he required for his home. While closets received rim locks, Jefferson ordered twenty-six mortise locks for use in the principal rooms. Depictions of available mortise lock hardware, including not only lock mechanisms themselves but also escutcheon plates and door pulls, were widely available in the early nineteenth century in trade catalogues. However, the locks were still expensive and difficult to obtain at this time.[2] Jefferson ordered his locks from Paris. Similarly, mortise locks were used in primary rooms in 1819 at Decatur House in Washington, D.C. while rim locks were used in closets and other secondary spaces.[3]

The mortise locks used at Monticello were warded locks.[2] The name warded locks refers to the lock mechanism, while the name mortise lock refers to the bolt location. Warded locks contain a series of static obstructions, or wards, within the lock box; only a key with cutouts to match the obstructions will be able to turn freely in the lock and open the latch.[4]

Warded locks were used in Europe throughout the medieval period and up until early 19th century. Three British locksmiths, Robert Barron, Joseph Bramah, and Jeremiah Chubb, all played a role in creating modern lever tumbler locks. Chubb's lock was patented in 1818. Again, the name refers to the lock mechanism, so a lock can be both a mortise lock and a lever tumbler lock. In the modern lever tumbler lock, the key moves a series of levers that allow the bolt to move in the door.[5]

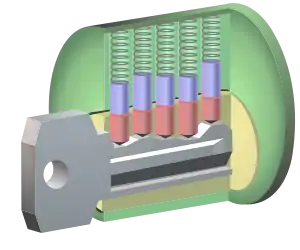

The next major innovation to mortise lock mechanisms came in 1865. Linus Yale, Jr.'s pin tumbler mortise cylinder lock put not only the latch or bolt itself inside the door, but also the tumblers and the bolt mechanism. Up to this point, the lock mechanism was always on the outside of the door regardless of the bolt location. This innovation allowed keys to be shorter as they no longer had to reach all the way through a door. Pin tumbler locks are still the most common kind of mortise lock used today.[5]

Mechanism

Mortise locks may include a non-locking sprung latch operated by a door handle. Such a lock is termed a sash lock. A simpler form without a handle or latch is termed a 'dead lock'. Dead locks are commonly used as a secure backup to a sprung non-deadlocking latch, usually a pin tumbler rim lock.[note 1]

Mortise locks have historically, and still commonly do, use lever locks as a mechanism. Older mortise locks may have used warded lock mechanisms. This has led to a popular confusion, as the term 'mortise lock' is usually used in reference to lever keys. In recent years the Euro cylinder lock has become common, using a pin tumbler lock in a mortise housing.

The parts included in the typical US mortise lock installation are the lock body (the part installed inside the mortise cut-out in the door); the lock trim (which may be selected from any number of designs of doorknobs, levers, handle sets and pulls); a strike plate, or a box keep, which lines the hole in the frame into which the bolt fits; and the keyed cylinder which operates the locking/unlocking function of the lock body. However, in the United Kingdom, and most other countries, mortise locks on dwellings do not use cylinders, but have lever mechanisms.

Installation

The installation of a mortise lock can be undertaken by the average homeowner with a working knowledge of basic woodworking tools and methods. Many installation specialists use a mortising jig which makes precise cutting of the pocket a simple operation, but the subsequent installation of the external trim can still prove problematic if the installer is inexperienced.

Although the installation of a mortise lock actually weakens the structure of the typical timber door, it is stronger and more versatile than a bored cylindrical lock, both in external trim, and functionality. Whereas the latter mechanism lacks the architecture required for ornate and solid-cast knobs and levers, the mortise lock can accommodate a heavier return spring and a more solid internal mechanism, making its use possible. Furthermore, a mortise lock typically accepts a wide range of other manufacturers' cylinders and accessories, allowing architectural conformity with lock hardware already on site.

Some of the most common manufacturers of mortise locks in the United States are Nostalgic Warehouse, Accurate, Arrow, Baldwin, Best, Corbin Russwin, Emtek Products, Inc, Falcon, Penn, Schlage, Sargent and Yale. Also, many European manufacturers whose products had been restricted to "designer" installations have recently gained wider acceptance and use.

Notes

- The type commonly called a 'Yale' lock.

References

- Schiffer, Herbert. Early Pennsylvania Hardware. Box E. Exton: Schiffer Publishing, Inc., 1966.

- Self, Robert (2004). "Restoration of Door Hardware at Monticello: Unlocking Some Mysteries". APT Bulletin. 35 (2–3): 7–15. doi:10.2307/4126400. JSTOR 4126400.

- Cliver, E. Blaine (1974). "Comment on a Mortise Lock". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 6 (2): 34–35. doi:10.2307/1493421. JSTOR 1493421.

- Bill, Phillips. The Complete Book of Locks and Locksmithing. pp. 60, 62.

- "The Evolution of Everyday Objects: the History of the Key. Slate Magazine.

- Peter Brett. Carpentry and Joinery Nelson Thornes, 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mortice locks. |