Mosaic ceiling of the Florence Baptistery

The Mosaic ceiling of the Florence Baptistery is a set of mosaics covering the internal dome and apses of the Baptistery of Florence. It is one of the most important cycles of medieval Italian mosaics, created between 1225 and around 1330 using designs by major Florentine painters such as Cimabue, Coppo di Marcovaldo, Meliore and the Maestro della Maddalena, probably by mosaicists from Venice.

History

The first mosaics were created in the apse by the Franciscan monk Jacopo, whom Vasari's Lives of the Artists wrongly supposed to be Jacopo Torriti. An inscription split between the four apses gives the start-date for the work.[1]

Producing the mosaics was a difficult and expensive undertaking. The Arte di Calimala was responsible for decorating and maintaining the Baptistery and in 1271 it signed an agreement with the canons to start decorating the interior of the dome, though it is now thought that the mosaics on the portion nearest the lantern may have been begun in 1228 by the same Jacopo, soon after the "scarsella" (rectangular apse) was completed. The works continued until the start of the 14th century, ending around 1330, as reported by a passage in the work of Giovanni Villani.

According to Vasari the earliest mosaics was by Andrea Tafi, a semi-legendary figure, who produced the angelic hierarchies and the Pantocrator assisted by Apollonio, a Greek he had met in Venice. He attributed the rest of the work to Gaddo Gaddi. It is impossible to confirm Vasari's account, though the earliest mosaics are also the most similar to those in San Marco Basilica, Santa Maria Assunta Basilica, other Venetian locations and Rome's San Paolo fuori le Mura, where the Venetian masters also worked after being summoned by Pope Honorius III in 1218.[2]

Most art historians now attribute the compositions to a number of Tuscan artists but their realisation to mosaicists from Venice or the eastern Mediterranean. Stylistic analogies with painted works enable links with the best 13th century masters, their collaborators, Giotto and the 'proto-Giottists' such as the so-called Last Master of the Baptistery identified by Roberto Longhi.[2] The works have been under almost constant restoration from the late 14th century onwards, with particularly notable schemes occurring in 1402, 1481, 1483–1499 (overseen by Alesso Baldovinetti, who was made "official restorer of the mosaic decoration"), 1781–1782 (general cleaning), 1821–1823 (dealing with serious damage in the area of Stories of Noah) and 1898–1907 (massive reintegration).[2]

Iconography

Apse

The double arch over the altar is decorated with busts of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the apostles and prophets, divided into compartments and decorated with leaves, possibly later work from the end of the 13th century. On the rectangular apse is a frieze with cherubim and seraphim between clipei, over which are the vault mosaics by Brother Jacopo, which show some connection with those in San Marco Basilica in Venice.[1]

At either end are mixti-linear figures with inscribed tablets above them – on these are four very ornate capitals in lively colours with very articulated lines, on which stand four telamons, folded to look like wheels. The telamons have a lively plasiticity and resemble sculptures by the studio of Benedetto Antelami on the facade of Fidenza Cathedral. To the left side of the telamons is an enthroned John the Baptist and to the right the Madonna and Child enthroned – both those panels are heavily restored, particularly the heads. The thrones are modelled on Carolingian and Ottonian miniature painting.[1]

The wheel's structure is formed of classical swirls with rays containing candelabra, whose fantastical composition seem to anticipate 15th and 16th century grotesque art. Below is a vase between two facing animals such as deer (recalling Psalm 41's "as the deer seeks water, so the soul seeks God"), birds and strange fish-men with fins on their heads.

Above is a vegetable motif with a small head in the middle and higher up an angel holding the large central medallion, in which is written "Agnus Dei". Around the medallion is inscribed "HIC DEUS EST MAGNUS MITIS QUEM DENOTAT AGNUS" ("here is great God shown as a mild lamb") in gold letters on a red background. Between the rays are eight full-length depictions of prophets in Byzantine style with name labels at their feet – anticlockwise these are Moses, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Daniel, Ezekiel, Jermiah and Isaiah.

Side view

Side view Busts and plant motifs

Busts and plant motifs Busts and plant motifs

Busts and plant motifs

Dome

Covered with mosaics on gold backgrounds, the interior of the dome is split into eight segments. Some argue Venetian masters were involved, with local artists such as Coppo di Marcovaldo (Hell) and Meliore di Jacopo (parts of Paradise) providing cartoons.

The upper frieze (2) shows the angelic hierarchies around all eight segments, whilst the rest of three segments (1) shows the Last Judgement, dominated by a huge figure of Christ, under whose feet is shown the resurrection of the dead. To Christ's right are shown the just welcomed into heaven, whilst on the left is hell and its devils.

The other five segments are subdivided into four horizontal registers showing (from top to bottom) stories from the Book of Genesis (3) and the lives of Joseph (4), the Virgin Mary (5), Christ (5) and John the Baptist (6). The first scenes from the Baptist's life are thought to be from cartoons by the Master of the Maddalena and Cimabue.

Angelic hierarchies

The closest part to the centre of the dome contains a series of frames with lively plant-form decoration, followed by a band with spirals and rhythmic figurative images reminiscent of the wheel in the apse – in each corner is a kind of vase made of fantastical plant elements, aligned to small columns in the lowest register. From the vases emerge two stalks which create large volutes and a central branch. Where the symmetrical volutes join and above the central elements are small heads between clipei and under the volutes are elaborate fountains, from which deer, peacocks, rams, herons and other animals drink, all based on early Christian art. Below this band runs a frame of shells.

The next ring illustrates Pseudo-Dionysius's angelic hierarchies with captioned images. At the centre is Christ Blessing, with an open book in his hand and flanked by red seraphim and blue cherubim, with the closest to him distinct in having three pairs of wings. Next, alternating from left to right and separated by small columns, are two pairs of each kind of angel. These all have two wings and are all identical to their pair, except for those on the same axis as Christ which are mirror images of each other:

- Thrones – charged with bearing God's throne in heaven and shown holding shining mandorlas, a conventional Byzantine symbol for God's throne[3]

- Dominions – the order of the universe depends on them; they are shown with a long sceptre surmounted by a three-leafed clover, a symbol of the Holy Trinity

- Virtues – charged with dispensing God's grace; they call demons out of small possessed men seated on blocks beside them

- Powers – charged with distributing powers to humanity and shown wearing crested helmets

- Principalities – charged with watching over the nations and shown holding crusader banners

- Archangels – the major counsellors sent from heaven, they are shown dressed in elegant robes and holding cartouches, symbolising God's messages

- Angels – the closest rank of angel to humans and thus put in charge of their preoccupations

According to Pietro Toesca, the artist behind the first register was the same brother Jacopo who worked on the rectangular apse, assisted by Venetian masters.[2] The angelic hierarchies are traditionally attributed to Andrea Tafi and Apollonio, though Ragghianti argues Coppo di Marcovaldo produced the cartoon for the figure of Christ and the Master of the Maddalena that for the Powers.[2]

Last Judgement

The three segments above the altar show the Last Judgement, with the centre almost completely filled by a figure of Christ the Judge seated on the Circles of Paradise and holding out his hands, showing his wounds from the Crucifixion, one facing palm up and the other palm down, directing souls to heaven and hell respectively. The large feet also show the wounds from the Crucifixion – their staggered pose, the robe's complex pleats and the side view of the legs avoid a rigid frontal effect, highlighted with golden tesserae. The cruciform halo includes mirror-like enamel cubes, also included in the border of the mandorla around Christ. Either side of the mandorla are three parallel registers, with two almost symmetrical hosts of angels at the top bearing symbols of Christ's passion and attributes of the Judgement, along with two angels sounding the last trumpet of the Apocalypse summoning the dead from their graves at Christ's feet.

In the second register are the Virgin Mary (with raised hands to Christ's right), John the Baptist (holding a scroll to Christ's left) and the twelve apostles seated on two long benches decorated as thrones. Each apostle holds an open book with characters from a different alphabet to show their taking the Gospel to the whole world after Pentecost. Behind the backrests and between the saints are angel heads, alternating in tilt from right then to left. Ragghianti (1957) assigned these scenes to Meliore, particularly comparing the figure of St Peter to Meliore's Christ the Redeemer with Four Saints (Uffizi).

The lower register shows Paradise to the right and Hell to the left, with the souls taken to their destinations by angels and devils. The elect are driven towards a group giving thanks to God and accompanied by a large angel holding a scroll reading "Venite Beneditti Patris Mei / Ossidete Preparatum" ("Come, [ye] blessed of my father / sit in the places prepared [for you]")[4] towards the Heavenly Jerusalem. Another angel in gem-decorated clothes opens the gateway to a small man, dragging him by the hand. In the city three large patriarchs sit holding small sweetbreads in their laps amidst extraordinary colourful plants in a green flower-dotted meadow, the latter symbolised by a band. In the front row of the elect are a king and a Dominican monk, followed by three virgins, bishops, a monk and a priest.

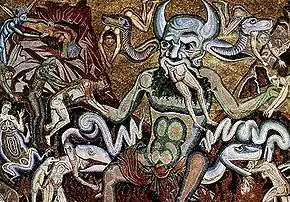

Art historians unanimously attribute the composition of the scene of Hell to Coppo di Marcovaldo, with less skillful areas by other hands.[2] Hideous devils with black bat-wings push the damned towards Christ's left. The damned souls trample and crowd each other, covering their eyes and mouths in disgust. Hell is dominated by a large Satan on a flaming throne, eating a man and trampling the damned while snakes growing out of his ears bite at them. Monsters shaped like snakes, frogs and lizards also emerge from his body and attack the damned, emphasising Satan's insatiable nature. Satan's ass's ears underline his feral nature and are attributes of Lucifer and the Antichrist, whilst his horns derive from the Celtic god Cernunnos and symbolise the Church's defeat of paganism.[5] Devils also throw the damned into pits, impale and mutilate them, burn them on spits, throw them around and force them to drink molten gold. One group of damned souls is wrapped in flames.

Last Judgement

Last Judgement The Heavenly Jerusalem

The Heavenly Jerusalem Apostles and Hell

Apostles and Hell Satan

Satan

Stories from Genesis

In the first register below the angelic hierarchies are stories from the Book of Genesis, three in each segment. Anti-clockwise, these show:

| Image | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Creation of the Elements | Pesenti argues it is by a follower of Giotto or by Gaddo Gaddi, with Sienese influences. |

| Creation of Adam | Heavily restored after damage in 1898–1907; only God's head and a small piece of the background are original |

| Creation of Eve | Figure of God almost entirely reconstructed in the 1898–1907 restoration. |

| Fall of Man | The crown of the tree, Eve's head and the serpent's head are restorations. Like the other scenes from Genesis, it is attributed to Gaddo Gaddi. |

| God Reprimands Adam and Eve | Head of God and other parts of the bodies of Adam and Eve are reconstructed. |

| Exile from Paradise | The angel's wings and most of Adam's body are restorations. |

| Adam and Eve Working | Other than the mound on the right, the whole section is original. |

| Sacrifices of Cain and Abel | Abel offers a lamb and Cain a bundle of corn, with God's hand reaching towards the lamb. The altar and the whole lower area around it are restorations. |

| Cain Kills Abel | The crown of the tree, the figure of God, the rocks and the dead Abel are restorations. |

| Lamech kills Cain and Tubalcain | Original panel collapsed in 1819; replaced in 1906 by a design by Arturo Viligiardi. |

| God Orders Noah to Build the Ark | Original panel collapsed in 1819; replaced in 1906 by a design by Arturo Viligiardi. |

| Noah Builds the Ark | Original panel collapsed in 1819; replaced in 1906 by a design by Arturo Viligiardi. |

| Noah and the Animals Enter the Ark | Double scene, showing a certain modernity in the animals. Ponticelli attributed it to a 1483–1499 intervention by Alesso Baldovinetti, inspired by Paolo Uccello's frescoes Scenes from the Life of Noah in the Chiostro Verde of Santa Maria Novella. Roberto Longhi instead argued the mosaic was earlier than the fresco, with the latter drawing on the former. Soulier noted Egyptian or Syriac influence. |

| The Flood | Traditionally attributed to Gaddo Gaddi. |

Stories of Joseph

In the second register below the angelic hierarchies are stories from the life of Joseph, also divided into three per segment and read anti-clockwise:

| Image | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Joseph's First and Second Dream | The first three scenes from the life of Joseph, rich in chiaroscuro and sfumato, were attributed by Pesenti (1978–1979) to the circle of Coppo di Marcovaldo, especially the first scene showing Joseph as a boy dreaming of eleven sheaves of wheat (representing his eleven half-brothers) bowing before a twelfth sheaf (representing Joseph) and of the sun (representing their father) and moon (representing their mother) looking at him and ignoring the other eleven stars (the half-brothers). These scenes were washed in 1898–1905, when the enamel was also tessellated and some gaps filled. |

| Joseph Telling His Parents His Dreams | Roberto Longhi (1939) attributed this scene to the artist behind The Flood, linked to north European art, though Pesenti attributed it to Coppo di Marcovaldo's circle. The figure of Joseph and three of his brother's heads on the right are restorations. |

| Joseph Telling His Half-Brothers His Dreams | Roberto Longhi (1939) attributed this scene to the artist behind The Flood, linked to north European art, though Pesenti attributed it to Coppo di Marcovaldo's circle. It contains no restorations. |

| Joseph's Brothers Throw Him Down a Well and Sell Him | The composition and the types of faces and drapery in this and the next two scenes are linked to Cimabue (Mario Salmi, Roberto Longhi, Roberto Salvini), though their tone has also seen them linked to the Master of the Maddalena. |

| The Half-Brothers Showing Joseph's Bloodied Clothes to their Father Jacob | Pesenti and others attribute its inspiration to Cimabue, possibly then drawn by the Master of the Maddalena and then worked up by the mosaicists. |

| Joseph Taken to Egypt by the Ishamaelites | As with the previous scene it is attributed to the Master of the Maddalena. The two merchants on the right are late 19th century restorations. |

| Potiphar Buys Joseph from the Ishmaelite Merchants | Ragghianti attributes the next three scenes to the circle of the Master of the Maddalena, with patterns similar to those in Mary Magdalene with Eight Scenes from her Life (Galleria dell'Accademia). |

| Joseph Arrested on the False Accusation of Potiphar's Wife | As the previous scene. |

| Joseph Interpreting the Cupbearer's and Baker's Dreams in Prison | Stylistically similar to the scene of Joseph before Potiphar. |

| Pharaoh's Dreams | It differs from the preceding scenes by a richer palette of colours, though this could be due to a different mosaicist, whilst its lively composition in almost pathetic tones may attribute them to the Master of the Maddalena (Pesenti, 1978–1979). The curtain over Pharaoh's bed is a late 19th-century restoration. |

| Joseph Interpreting Pharaoh's Dream | It differs from the preceding scenes by a richer palette of colours, though this could be due to a different mosaicist, whilst its lively composition in almost pathetic tones may attribute them to the Master of the Maddalena (Pesenti, 1978–1979). No substantial restorations. |

| Joseph Given Command over Egypt | It differs from the preceding scenes by a richer palette of colours, though this could be due to a different mosaicist, whilst its lively composition in almost pathetic tones may attribute them to the Master of the Maddalena (Pesenti, 1978–1979). |

| Joseph Watches his Half-Brothers Loading Grain | Longhi attributes it to the master of The Flood, who he called the Last Master of the Baptistery, putting him closer to the style of Gaddo Gaddi. Others such as Luciano Bellosi argue that it was by a master from Giotto's circle drawing on the Scrovegni Chapel, with Pesenti adding the detail of influence from the Sienese school. |

| Giuseppe Reconciled with his Half-Brothers | Longhi attributes it to the master of The Flood, who he called the Last Master of the Baptistery, putting him closer to the style of Gaddo Gaddi. Others such as Luciano Bellosi argue that it was by a master from Giotto's circle drawing on the Scrovegni Chapel, but Pesenti placing them closer to the Scenes from the Life of Joseph in the Upper Basilica at Assisi. Longhi also noted the similarity in the composition of the figures to those in St Francis in the Chariot of Fire fresco in Assisi. | |

| Jacob Meets Joseph | It differs from the preceding scenes by a richer palette of colours, though this could be due to a different mosaicist, whilst its lively composition in almost pathetic tones may attribute them to the Master of the Maddalena (Pesenti, 1978–1979). |

Lives of Mary and Christ

| Image | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Annunciation | Pesenti attributes it to the circle of Coppo di Marcovaldo based on its similarities to the Annunciation on the Madonna-Reliquary of Santa Maria Maggiore, though the latter work is now reattributed to a 1200–1250 Byzantine master. |

| Visitation | Its cartoon is attributed to Cimabue. The middle of the woman to the left was restored in the late 19th century. |

| Nativity | Its cartoon is attributed to Cimabue. Part of St Joseph's drapery is a restoration. |

| Adoration of the Magi | Pesenti dates it to the late 13th century and attributes it to the Master of the Maddalena. |

| The Magi's Dream | Pesenti dates it to the late 13th century and attributes it to the Master of the Maddalena. |

| The Magi's Return Journey | Pesenti dates it to the late 13th century and attributes it to the Master of the Maddalena. |

| Christ Presented in the Temple | Pesenti attributes it to the Master of the Maddalena, but noted a different artist's work in the figures of the Christ Child and Simeon, attributing these instead to an artist with a more Byzantine training, though not the same artist as Christ the Judge. He argued that second artist's style was more nervous and included fuller drapery. Anna holds a scroll with a pseudo-Hebrew inscription. |

| St Joseph's Dream | Attributed to the Master of the Maddalena. |

| Flight into Egypt | Attributed to the Master of the Maddalena. |

| Massacre of the Innocents | The crowds of people and the dynamic style of this scene and the one below it from the life of John the Baptist led Longhi to link it to the "Carolingian Baroque" and Gaddo Gaddi, speaking of a generic "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery". Pesenti agreed, noting the scene's technical peculiarities. |

| Last Supper | The crowds of people and the dynamic style of this scene and the one below it from the life of John the Baptist led Longhi to link it to the "Carolingian Baroque" and Gaddo Gaddi, speaking of a generic "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery". Pesenti agreed, noting the scene's technical peculiarities. Venturi also saw strong similarities with Roman mosaics and Cosmatesque inlays and linked its massively robust figures to Cimabue's work, though Toesca and Mario Salmi argued against Cimabue's involvement. The most commonly-held theory now attributes the scene to the "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery", the most lively artist working on the cycle, characterised by strong plasticity. |

| Judas Betrays Christ | The crowds of people and the dynamic style of this scene and the one below it from the life of John the Baptist led Longhi to link it to the "Carolingian Baroque" and Gaddo Gaddi, speaking of a generic "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery". Pesenti agreed, noting the scene's technical peculiarities. Venturi also saw strong similarities with Roman mosaics and Cosmatesque inlays and linked its massively robust figures to Cimabue's work, though Toesca and Mario Salmi argued against Cimabue's involvement. The most commonly-held theory now attributes the scene to the "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery", the most lively artist working on the cycle, characterised by strong plasticity. |

| Crucifixion | Attributed to the Last Master of the Baptistery, who worked there around 1285–1295 on the last segment of the dome alongside Gaddo Gaddi. His work is marked by expressiveness and plasticity with compositional balance in a proto-Giotto style. It was restored in 1481, possibly by Alesso Baldovinetti, with the modelling of Christ's body, the drapery of the loincloth, the Virgin Mary's clothes and the left-hand woman's clothes all attributed to him. |

| Lament over the Dead Christ | Attributed to the so-called Last Master of the Baptistery. |

| The Women at the Tomb | Attributed to the so-called Last Master of the Baptistery. The cycle does not include a scene of the Resurrection itself, since Christ the Judge is also shown as the Risen Christ. |

Stories of St John the Baptist

The Baptistery is dedicated to John the Baptist and the scenes from his life occupy the lowest register on the dome. They run in the same sequence as the other scenes, though with more scenes due to the longer space available in this register:

| Image | Title | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annunciation to Zaccharias | Its cartoon is attributed to Cimabue. | ||

| Birth and Naming of John the Baptist |

| ||

| John in the Desert | Attributed to an unknown Florentine artist. The mountain is shown as chipped rocks lit in the most prominent areas in the Byzantine style and is also described in the Libro dell'arte by Cennino Cennini. Part of the scene is a 19th-century restoration. | ||

| John Preaching in the Desert | Attributed to a Florentine painter. | ||

| John Baptising the Crowds | Attributed to a Florentine painter. | ||

| John Pointing to Christ as the Lamb of God | Attributed to a Florentine painter. | ||

| Baptism of Christ | Attributed to a drawing by Cimabue, showing elements of Byzantine convention such as Christ being covered with water up to his chest and no water exuding on the sides, as painted by Giotto in his Baptism of Christ in the Scrovegni Chapel. | ||

| John Condemning Herod Antipas for Marrying Herodias | Attributed to a Florentine painter. | ||

| John in Prison | Attributed to the "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery" and Gaddo Gaddi by Roberto Longhi, who identified both as inventing a style he called "Baroque" and which he also saw in other scenes in this segment. | ||

| John's Disciples Visit Him in Prison | Attributed to the "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery" and Gaddo Gaddi by Roberto Longhi, who identified both as inventing a style he called "Baroque" and which he also saw in other scenes in this segment. | ||

| John's Disciples Witness Christ's Miracles | Attributed to the "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery" by Roberto Longhi | ||

| Herod's Banquet | Called another "Baroque" scene by Longhi; attributed to the "Penultimate Master of the Baptistery". | ||

| John Beheaded | Florentine school, distinguished by the violent representation of the execution and the expressiveness of the executioner's gesture. | ||

| Salome Presents John's Head to the Banqueters | Florentine school. | ||

| Burial of John | Florentine school; also attributed by some to Cimabue. |

Women's galleries

The last part of the interior to have mosaics added were the women's galleries between approximately 1300 and 1330.[1] These show angels and saints and their style agrees with Giovanni Villani's written evidence, which dates their completion to 1330 and probably dates the start of work to around 1300–1315. There are no art historical studies specifically on the mosaics of the women's galleries, though Venturi briefly notes that they were produced after 1300. The vault has a central motif of a starry sky, symbolic of the Empyrean, surrounded by angels with unclear attributes, possibly another set of angelic hierarchies.

Other mosaics

A frieze of panels runs around the base of the dome, showing saints, dating to the late 14th century from drawings by Lippo di Corso. They show saints:

- Ambrose

- Gregory Nazianzenus (?)

- Jerome

- Augustine

- Stephen

- Leo

- Isidore

- Philip (?)

- Sylvester

- Nicholas of Bari

- Unknown Martyr Deacon

- Ignatius

- Dionysius

- Unknown Deacon

- Basil

- Protasius (?)

- Gregory the Great

- Cyprian the Bishop

- Vincent

- Fulgentius

- Martin

- Unknown Deacon

- Zanobius

- Hilarius

- Lawrence (?)

- John Chrysostom (?)

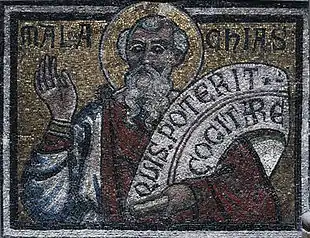

The women's galleries instead bear panels of prophets and patriarchs, attributed to the late 13th century Gaddo Gaddi by Vasari, who also states they were produced without studio assistance, though modern art historians also recognise the hands of his workshop and Andrea Tafi in them. They show:

- Isaiah

- Jeremiah

- Daniel

- Ezekiel

- Hosea

- Joel

- Obadiah

- Amos

- Micah

- Jonah (?)

- Nahum

- Habbakuk

- Zephaniah

- Haggai

- Zaccarias

- Malachi

- David

- Solomon

- Matathias

- Judas Macabeus

- Nehemiah

- Esra

- Zerubbabel

- Jozadak (?)

- Elisha

- Onias

- Samuel

- Joshua

- Noah

- Baruch

- Isaac

- Abraham

- Enoch

References

- Touring, cit. p. 152.

- Article on the dome

- Frugoni, cit., pp. 222–223.

- cf. "venite benedicti Patris mei possidete paratum vobis regnum a constitutione mundi" Vulg.: Matt. 25:34

- (in Italian) Simboli e allegorie, Dizionari dell'arte, ed. Electa, 2003, pag. 158.

- Sindona, cit., p. 87.

Bibliography (in Italian)

- AA.VV., Guida d'Italia, Firenze e provincia "Guida Rossa", Touring Club Italiano, Milano 2007.

- Enio Sindona, Cimabue e il momento figurativo pregiottesco, Rizzoli Editore, Milano, 1975. [ISBN unspecified]

- Chiara Frugoni, La voce delle immagini, Einaudi, Milano 2010. ISBN 978-88-06-19187-0

External links

- "Apse mosaics" (in Italian).

- "Dome mosaics" (in Italian).

- "Mosaics of the first women's gallery" (in Italian).

- "Mosaics of the second women's gallery" (in Italian).

- "Mosaics of the third women's gallery" (in Italian).

- "Mosaics of the fourth women's gallery" (in Italian).